Arxiv:Math/0302257V1 [Math.PR] 20 Feb 2003 Eeaietento Fasaei Re Ogv Ipepofo U a Our of Proof Simple a Give to Order T in in Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IJA Enewsletter Editor Don Lewis (Email: [email protected]) Renew At

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION June 2015 IJA eNewsletter editor Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http://www.juggle.org/renew IJA eNewsletter IJA Festival July 20 - 26, 2015 Quebec City, QC, Canada Register online soon! Discounts on Contents: Event Packages end June 30! IJA Pre-Reg Deadline Only Days Away Full info is on our website: Chairman’s Message www.juggle.org/festival IJA Election - New, Vote Online! Candidates’ Statements After June 30th, Stage Championships Finalists Register in Person at the Festival IJA Festival Information Online IJA Fest’s Special Guests See fest details starting on page 4, Festival Checklist where the Championships Finalists are listed! WJD shirts, YJA badges in IJA Store What’s New at eJuggle Coming Soon to eJuggle... Juggling Festivals Juggling Festivals: Lincolnshire, UK Eugene, OR Quebec City, Quebec, Canada (IJA) Collinée en Bretagne, France Bruneck, South Tyrol, Italy (EJC) Montpeyroux, France Garsington, Oxfordshire, UK Cleveland, OH Portland, OR Kansas City, MO Philadelphia, PA Fukushima, Japan Ottumwa, IA WWW.JUGGLE.ORG Page 1 THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION June 2015 Chairman’s Message, by Nathan Wakefield - Obstacle course: $500 - Waterballoon slip and slide: $200 - Drinks and flair bartender: $200 - Onsite massage therapist: $1,000 - Cardboard box castle building contest: $60 - Pinata filled with juggling props: $250 - Tye Dye $60 "To render assistance to fellow jugglers." - Food. $1,630 and the remainder of any additional funds. Special thanks to donor Unna Med and all those who Less than one month until the 2015 IJA Festival in contributed towards this fund of awesomeness! Quebec City! It's been a long road of hard work for our festival team If logistics is an issue for you, we have rideboards and officers, but everything is in place for this year's available on both our festival forum and on Facebook. -

Fargo Convention Well Worth the Journey

August 1980 Vol. 32 No. 5 Membership—1,200 1981 Convention Site—Cleveland, OH, Case Western Reserve University Fargo convention well worth the journey In anticipation of sharing talent and watching jugglers in the crowded party room witti the promise Benefit shows for crowds at the NDSU student some of the best jugglers in North America at work, of greater support if the IJA would return to Fargo union, the Red River Mall, a Shrine club and a 475 people trekked through mid July heat to Faigo, nextyear. Reaction was not positive, and conven- nursing home demonstrated IJA’s appreciation ND, site of the 33rd IJA annual convention, tioneers later voted Cleveland. OH, as the 1981 for the hospitality, There, close by the geographical center of the site (see page 6). The convention ran smoothly, and largely on time. continent, they witnessed the basics—like 3-ball High-rise lodging contained two-story foyer areas and 5-club cascades—and the outer limits of jug that were ideal for juggling. The university food gling skill, as demonstrated by Michael Kass’s prize service fed 165 jugglers three times day, and cater winning performance of club kick-ups. The same ed a pleasant outdcxar "buffalo" barbeque at Troll- lure of communion with fellow jugglers has drawn wood Park on Saturday. this group together annually since 1947, when The Saturday morning parade included many the founding fathers formed the group during a other area groups, and was aired by NBC news convention of the international Brotherhood of on a late-night broadcast. -

Car Agency in Lakewood Going to the Dogs!

July 7th, 2016 The Ocean County Gazette - www.ocgazette.news 1 The OC Gazette P.O. Box 577 Seaside Heights NJ 08751 On The Web at: www.ocgazette.news JULY 29TH, 2016 VOL. 16 NO. 570 THIS WEEKS Car Agency in Lakewood Going ALERT SHERIFF’S ISSUE OFFICER CATCHES Pages 8-9 to the Dogs! Ocean County POSSIBLE BURGLARY Featured Events FROM COURTROOM Pages 10-11 Ocean County WINDOW; WARRANT Library Weekend Events and ISSUED Exhibits TOMS RIVER – The keen eye of Pages 12-13 an Ocean County Sheriff’s Officer Ocean County caught a suspicious male gaining Artists Guild entry into an apartment on Washington Street in the downtown Page - 16-17 area on July 21. And now, that Long Beach Island Foundation of the person has a warrant out for his Arts & Sciences arrest on charges of burglary, theft Events and criminal trespassing. According to a report provided Page 25 by Ocean County Sheriff Michael Museums, Historic, G. Mastronardy, Sheriff’s Officer Arts & Exhibits Robert Mazur was just completing Photo credits: Courtesy of Caregiver Volunteers; Picture of Alice, courtesy of Michael his security detail around noon in Page 25 Bagley Photography Alice, Lavallette, with Golden Retriever Simon Courtroom 214 on the third floor A Summary of of 213 Washington St., when he Comedy & Stage glanced out the window toward the Performances Kick off the “Dog Days of Summer” $5.00 to the nonprofit Caregiver with a celebration of Caregivers, Canines® program for every vehicle Harbor Front Condominiums at 215 Page 27-34 Canines, and Cars at the Larson Ford sold during the Caregivers, Canines, Washington Street. -

In-Jest-Study-Guide

with Nels Ross “The Inspirational Oddball” . Study Guide ABOUT THE PRESENTER Nels Ross is an acclaimed performer and speaker who has won the hearts of international audiences. Applying his diverse background in performing arts and education, Nels works solo and with others to present school assemblies and programs which blend physical theater, variety arts, humor, and inspiration… All “in jest,” or in fun! ABOUT THE PROGRAM In Jest school assemblies and programs are based on the underlying principle that every person has value. Whether highlighting character, healthy choices, science & math, reading, or another theme, Nels employs physical theater and participation to engage the audience, juggling and other variety arts to teach the concepts, and humor to make it both fun and memorable. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES This program will enhance awareness and appreciation of physical theater and variety arts. In addition, the activities below provide connections to learning standards and the chosen theme. (What theme? Ask your artsineducation or assembly coordinator which specific program is coming to your school, and see InJest.com/schoolassemblyprograms for the latest description.) GETTING READY FOR THE PROGRAM ● Arrange for a clean, well lit SPACE, adjusting lights in advance as needed. Nels brings his own sound system, and requests ACCESS 4560 minutes before & after for set up & take down. ● Make announcements the day before to remind students and staff. For example: “Tomorrow we will have an exciting program with Nels Ross from In Jest. Be prepared to enjoy humor, juggling, and stunts in this uplifting celebration!” ● Discuss things which students might see and terms which they might not know: Physical Theater.. -

The Compass, October 31, 2005

THE~C The Student Voice of Gainesville State College Vol. XL No. 2 October 31, 2005 Gainesville Siale College! Regents Approve GC Bid to Grant 4-year Degrees By Jessi Stone easier to remember. is www.gsc. Editor~in-Ch i ef edu and in January,lhe new email [email protected] fonnal will be [email protected] Don'l frel because the old Peach On Oct. 12. The Board of Re Net fonnal will sti ll work for one gents voted in favor of a new to two years until me transi tion is mission statemenllhal will allow completc. Besides the ncw name ase to offer the first in a series and email addresses. Nesbitt said of four-year baccalaureate pro GSC will still be mainly focused grams. The first four-year degree on Ihe first two year programs. that GSC will offer beginning Rest assured that luition will nOI next fall is a Bachelor of Science increase for students who are in Applied Environmental Sp..'ltial pursuing an Associale's degree aI Analysis. This bachelor's degree GSC. is not offered at any other institu GC has been Irying to become tion in the stale of Georgia. a four-year institution since 2002 The Iwo other baccalaureate when the chancellor announced programs that have been pro the opponunity for two-year col posed for the near future arc Ear leges to review their mission and ly Childhood Care and Education propose changes. GSC has now and Applied Business Tedmol enlercd into a new category of ogy. These programs have been chosen W10slly because GSC al Unh·erslty System of Georgia in ready has the facully as well as Ihe sti tutions. -

IJA Enewsletter Editor Don Lewis (Email: [email protected]) Renew at Http

THE INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS! ASSOCIATION December 2013 IJA eNewsletter editor Don Lewis (email: [email protected]) Renew at http:www.juggle.org/renew Compliments of the Season from the IJA Have a safe and happy holiday whatever you!re celebrating IJA eNewsletter 2013 Membership Drive Runs Through December 26 by Kyle Johnson, IJA Marketing Director We are happy to inform you about the 2013 Membership Drive that's happening now through December 26. "Membership prices are discounted, and you can even win a 2014 IJA Festival Event Package or other rewards. Check out our new promotional video showing the benefits of being an IJA member and Contents: a few things about the IJA you may not know. "You can help the IJA by sharing this video with fellow jugglers! http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbBofEAh1Qo Membership Drive IJA Festival Poster IJA Membership Drive 2013 IJA 2014 Festival News Save $5 off regular prices for IJA membership when you use the IJA Store to join or Special Friends Update renew by December 26th: More Lessons Learned Nominations Sought for Awards " Adults only $24.00 Dieter Tasso Book " Youths only $19.00 IJA Fest T-shirts Available And new and renewing members will be entered into raffles on December 21 & 28 with What!s New at eJuggle the following Raffle Prizes: Juggling Festivals • 2014 IJA Festival Package!! • Signed Anthony Gatto Playing Card! • Juggling Ring signed by the cast of the 2012 IJA Cascade of Stars Show"(Cie Ea Eo, Freddy Kenton, Doug Sayers, Pavel Evsukevich, ...) • Bronze Juggling Club Pendant! (Donated by David -

Braids and Juggling Patterns Matthew Am Cauley Harvey Mudd College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont HMC Senior Theses HMC Student Scholarship 2003 Braids and Juggling Patterns Matthew aM cauley Harvey Mudd College Recommended Citation Macauley, Matthew, "Braids and Juggling Patterns" (2003). HMC Senior Theses. 151. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmc_theses/151 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the HMC Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in HMC Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Braids and Juggling Patterns by Matthew Macauley Michael Orrison, Advisor Advisor: Second Reader: (Jim Hoste) May 2003 Department of Mathematics Abstract Braids and Juggling Patterns by Matthew Macauley May 2003 There are several ways to describe juggling patterns mathematically using com- binatorics and algebra. In my thesis I use these ideas to build a new system using braid groups. A new kind of graph arises that helps describe all braids that can be juggled. Table of Contents List of Figures iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Siteswap Notation 4 Chapter 3: Symmetric Groups 8 3.1 Siteswap Permutations . 8 3.2 Interesting Questions . 9 Chapter 4: Stack Notation 10 Chapter 5: Profile Braids 13 5.1 Polya Theory . 14 5.2 Interesting Questions . 17 Chapter 6: Braids and Juggling 19 6.1 The Braid Group . 19 6.2 Braids of Juggling Patterns . 22 6.3 Counting Jugglable Braids . 24 6.4 Determining Unbraids . 27 6.4.1 Setting the crossing numbers to zero. 32 6.4.2 The complete system of equations . -

We Will Certainly Defeat Terrorists: Rouhani

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 40,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13533 Wednesday NOVEMBER 20, 2019 Aban 29, 1398 Rabi’ Al awwal 22, 1441 Manoto TV funded Islamic states must Iran ready for CAFA U23 Books on war by Iranians’ looted pressure Riyadh to Women Championship against Daesh wealth 2 end Yemen war 3 2019: coach 15 honored in Tehran 16 Zarif calls U.S. claim of support We will certainly defeat for Iranians ‘shameful lie’ TEHRAN — Foreign Minister Moham- of supporting the Iranian people,” mad Javad Zarif said on Monday that the Zarif said. United States’ claims of support for the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo Iranian people is a “shameful lie”. on Saturday expressed support for riot- “A regime which imposes econom- ers in protests in Iran over increase in ic terrorism and prevents sending petrol price. terrorists: Rouhani food and medicine to ordinary peo- “As I said to the people of Iran almost ple, including the elderly and sick a year and a half ago: The United States is See page 2 ones, can never make obscene claim with you,” Pompeo tweeted. 2 Innocent detainees to be released soon: Judiciary TEHRAN — The spokesman for Iran’s who are innocent and have not commit- Judiciary says the innocent individuals ted arson or property damage, Gholam who were arrested in the recent protests Hossein Esmaeili told a press conference will be released soon. -

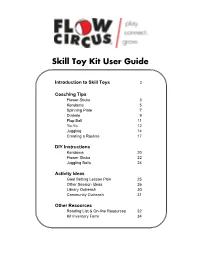

Skill Toy Kit User Guide

Skill Toy Kit User Guide Introduction to Skill Toys 2 Coaching Tips Flower Sticks 3 Kendama 5 Spinning Plate 7 Diabolo 9 Flop Ball 11 Yo-Yo 12 Juggling 14 Creating a Routine 17 DIY Instructions Kendama 20 Flower Sticks 22 Juggling Balls 24 Activity Ideas Goal Setting Lesson Plan 25 Other Session Ideas 26 Library Outreach 30 Community Outreach 31 Other Resources Reading List & On-line Resources 32 Kit Inventory Form 34 Introduction to Skill Toys Your teens are about to embark on a fun adventure into the world of skill toys. Each toy included in this kit has its own story, design, and body of tricks. Most of them have a lower barrier to entry than juggling, and the following lessons of good posture, problem solving, and goal setting apply to all. Before getting started with any of the skill toys, it is important to remember to relax. Stand with legs shoulder width apart, bend your knees, and take deep breaths. Many of them require you to absorb energy. We have found that the more stressed a player is, the more likely he/she will be to struggle. Not surprisingly, adults tend to have this problem more than kids. If you have teens getting frustrated, remind them to relax. Playing should be fun! Also, remind the teens that even the drops or mess-ups can give us valuable information. If they observe what is happening when they attempt to use the skill toys, they can use this information to problem solve. Try throwing it higher, try making the circle bigger, try holding it looser. -

Professional Juggling Equipment

Professional Juggling Equipment GB 2013 D Content Clubs 4 Diabolos 24 Fire 40 Juggling Balls 46 Juggling Props 50 Yo-Yos 56 Fon ++49 (0) 721-7 83 67-61|62|63 Öffnungszeiten/Working hours Henrys GmbH Fax ++49 (0) 721-7 83 67 77 In den Kuhwiesen 10 E-mail [email protected] 9.15 - 16.00 D-76149 Karlsruhe, Germany Internet www.henrys-online.de 9.15 - 14.00 Freitag/Friday 3 The Colorful World of Clubs Large color selection of handles, Knobs & Tops. Design your personal club. In the beginning ... ... it was pure joy and enthusiasm for juggling, and also the desire to do some useful work. Meanwhile Henrys has been setting standards in the production of precise and durable high-quality juggling The Colorful articles for about 25 years. Lots of innovations and product improvements in the field of juggling World of Clubs are based on our developments. If we are today ranking among the leading manufacturers of juggling articles in the world, this is due to the fact that we have preserved our idealism. Useful working does also mean working environmentally conscious and sustainable. All our products are mainly focussing on functionality and quality. Regardless of a general trend to manufacture abroad for reasons of cost and others, we are still trying to produce as many parts as possible in our own factory. Over the years we have therefore continuously been expanding our production lines. Today we have the latest injection and blow-moulding technologies as well as lathes, milling- and punching machines at our disposition. -

IJA Festival RFP 2024 R2

International Jugglers’ Association FESTIVAL SITE REQUIREMENTS 2024 updated 2019-08 INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS’ ASSOCIATION FESTIVAL SITE REQUIREMENTS introduction August, 2019 The International Jugglers' Association holds one event a year, it’s a week long, and it’s awesome. If we bring our event to your city, you will love having us there, you’ll miss us when we leave, and you’ll want us to come back again soon. We are now seeking a host city for our festival in 2024. Unfortunately, no one gets paid to attend a juggling convention. Everyone coming to an IJA festival is paying their own way, and most of them are traveling thousands of miles to attend our celebra- tion. Therefore, we are laser-focused on affordability of the festi- val venues, lodging and meals for our jugglers spending the week at the IJA festival. We will consider destinations for our future festivals only if all the economic and logistical factors look promising and can offer real affordability in lodging rates. Casino resorts, beach or mountain resorts and corporate conference centers generally do not provide us with the mix of affordability, choice and facilities we need for a successful week. Please see the accompanying materials for specifics on the require- ments for our festival, and some additional background informa- tion. Please note that this festival requirements document is extensive, but there are very few “show-stopper” items in it; i.e., we can work without or around nearly any item on the list if the bal- ance of your proposal is very attractive. I would be pleased to speak to you by phone to discuss how your city and facilities can fit into our plans for a future festival, before you begin preparing a formal proposal. -

Siteswap Ben's Guide to Juggling Patterns

Siteswap Ben’s Benjamin Beever ([email protected]) AD2000 Writings on juggling, for: 1) Jugglers 2) Mathematicians 3) Other curious people ABOUT THE BOOK The scientific understanding of ‘air-juggling’ has improved dramatically over the last 2 decades. This book aims to bring the reader right up to the forefront of current knowledge (or pretty close anyway). There are 3 kinds of people who might be reading this (see cover). As far as possible, I wanted to cater for everyone in the same book. Maybe this would help jugglers to appreciate maths, mathematicians to get into juggling, or even non-juggling, non-mathematicians to develop a favourable perception of the juggling game. In order to fulfil this ambition, I have indicated which parts of the text are aimed at a specific kind of reader. Different fonts have been used to indicate the main intended audience. Everyone (with many exceptions) should be able to understand most of the writings for the curious. However, non-jugglers may not be able to envisage the patterns discussed in the jugglers text, and non-mathematicians may find some of the concepts in the technical sections hard to get their grey matter around. I must point out however, that juggling is a fairly complicated business. It can be very hard to understand what’s going on in a juggling pattern when it’s being juggled in front of you, and it’s not always easy to understand on paper. This book introduces ‘Generalised siteswap’ (GS) notation, and shows how most air-juggling patterns can be formalised within the GS framework.