Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline of Mmos

The Decline of MMOs Prof. Richard A. Bartle University of Essex United Kingdom May 2013 Abstract Ten years ago, massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMOs) had a bright and exciting future. Today, their prospects do not look so glorious. In an effort to attract ever-more players, their gameplay has gradually been diluted and their core audience has deserted them. Now that even their sources of new casual players are drying up, MMOs face a slow and steady decline. Their problems are easy to enumerate: they cost too much to make; too many of them play the exact same way; new revenue models put off key groups of players; they lack immersion; they lack wit and personality; players have been trained to want experiences that they don’t actually want; designers are forbidden from experimenting. The solutions to these problems are less easy to state. Can anything be done to prevent MMOs from fading away? Well, yes it can. The question is, will the patient take the medicine? Introduction From their lofty position as representing the future of videogames, MMOs have fallen hard. Whereas once they were innovative and compelling, now they are repetitive and take-it-or-leave-it. Although they remain profitable at the moment, we know (from the way that the casual games market fragmented when it matured) that this is not sustainable in the long term: players will either leave for other types of game or focus on particular mechanics that have limited appeal or that can be abstracted out as stand-alone games (or even apps). -

381 Karlsen 17X24.Pdf (9.567Mb)

Emergent Perspectives on Multiplayer Online Games: A Study of Discworld and World of Warcraft Faltin Karlsen Doctoral thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. Faculty of Humanities, University of Oslo, June 2008. © Faltin Karlsen, 2009 Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Humanities,University of Oslo No. 381 ISSN 0806-3222 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Cover: Inger Sandved Anfinsen. Printed in Norway: AiT e-dit AS, Oslo, 2009. Produced in co-operation with Unipub AS. The thesis is produced by Unipub AS merely in connection with the thesis defence. Kindly direct all inquiries regarding the thesis to the copyright holder or the unit which grants the doctorate. Unipub AS is owned by The University Foundation for Student Life (SiO) Acknowledgements Thanks to my supervisor Gunnar Liestøl for constructive and enthusiastic support of my work, from our first discussions about computer games long before this project was initiated, to the final reassuring comments by phone from someplace between Las Vegas and Death Valley. Thanks to my second supervisor Jonas Linderoth for generously accepting my request and for thorough, precise and not least expeditious comments on various drafts during the last phase of my work. I would also like to thank Espen Ytreberg, Ragnhild Tronstad and Terje Rasmussen for reading and commenting on different parts of my thesis. A special thanks to Astrid Lied for introducing me to Discworld back in 1998, and for commenting on and proofreading parts of this thesis. -

Austin Games Conference 2005

Why are we here? 28 th october 2005 Austin games conference profesSor Richard A. Bartle University of esSEx introduction • It is a truth universally acknowledged… • that I’ve called this talk “why are we here?” – I include as “we” those who would have been here if they hadn’t been out ”Networking” until 2:30am this morning • I do mean the question quite literally: why are any of us in this location right now ? • This is actually a meaningful question… 1 Deep and meaningful Put another way • Point of fact: you are All goinG to DIE • Given this information, why are you here ? In this converted balLroOm ? • Why aren’t you in – paris? – China? – Darfur? – Bed? – World of warcraft ? • Hmm, I guess some of you are in there… 2 Short answer • Well, you’re here because you’re mMorpg developers and this is a mmorpg developers’ conference – officially, “networked game development” conference… • [aside: I’m gonna call them virtual worlds , not mMorpgs ] – I’m not giving up on my book’s title yet , dammit! • But this leads to another question: Another question • Why are you [mmorpg] virtual world developers? • Why aren’t you – regular game developers? – Novelists? – Truck drivers? – Nuclear power station software engineers? – Lawyers? – level 80 on runescape with 2 blue masks, 2 green masks, 2 santa hats and a red party hat ? • “Because it would cost me $5,100 on ebay” (44 bids, 13 hours to go, and simbatamer realLy wants it) 3 hackers • Notice the subtitle answers • Some posSible answers: – You’re a vw developer Purely by acCident – You wanted a -

Network Software Architectures for Real-Time Massively-Multiplayer

Network Software Architectures for Real-Time Massively-Multiplayer Online Games Roger Delano Paul McFarlane Degree of Master of Science School of Computer Science McGill University Montreal, Quebec, Canada Feb. 02, 2005 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Copyright © 2005 Roger Delano Paul McFarlane. All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my wife, Abaynesta, for her support and encouragement. Undertaking a full-time graduate degree while maintaining full-time employment and trying to be a full-time husband would have been an impossible challenge without your love, patience, and understanding. I love you. To my supervisor, Dr. Jörg Kienzle, I would like to express my thanks for taking on a student with a research area only somewhat related to your own, Software Fault Tolerance, and granting me the latitude to freely explore massively multiplayer game infrastructure. In the course of pursuing my graduate degree and writing this thesis, I was employed by two supportive organizations. To the management of Zero- Knowledge Systems Inc., most notably co-founders Austin Hill and Hammie Hill, I express my profound gratitude for your support and encouragement to pursue my academic goals. Thank you for allowing me the flexibility of schedule to take on a full-time course load and for your understanding and encouragement when the time came for me to move on to other opportunities. I would also like to thank the management of the Ubi.com group at Ubisoft Entertainment Inc. for recognizing the potential of this graduate student with no direct gaming experience and giving me the opportunity to learn from and contribute to your game projects while completing my thesis. -

Bojin-Diss-Library Copy

Exploring the Notion of ‘Grinding’ in Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Gamer Discourse: The Case of Guild Wars by Nis Bojin M.A. (Communication & Culture), York University, 2005 B.A. (Psychology/Classical Studies Double Major), York University, 2000 Dissertation Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the School of Interactive Arts and Technology Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Nis Bojin 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Nis Bojin Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Exploring the Notion of ‘Grinding’ in Massively Multiplayer Online Role Player Gamer Discourse Examining Committee: Chair: Halil Erhan Assistant Professor (SFU-SIAT) John Bowes Senior Supervisor Professor, Program Director (SFU- SIAT) Suzanne de Castell Co-Supervisor Professor (University of Ontario Institute of Technology) Jim Bizzocchi Supervisor Associate Professor (SFU-SIAT) Carman Neustaedter Internal Examiner Assistant Professor (SFU-SIAT) Sean Gouglas External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology (University of Alberta) Date Defended/Approved: May 29, 2013 ii Partial Copyright License iii Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or d. as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

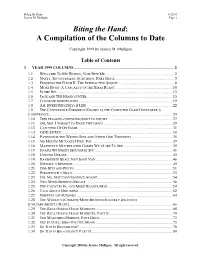

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29 -

What Is the Future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) What Is the Future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming?

What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) An undergraduate dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of CS335 - The Computing Dissertation module of BSc (Hons) Computer Science. I (Richard Slater) hereby certify that the content of this document has been produced solely by me in person according to the regulations set out by the University of Brighton, as such it is an original work. I so declare that any reference to non-original document or material has been properly acknowledged. Document Data Total Word Count 8944 Word Count 8090 excluding footnotes and annexes Modified 26 February 2004 By Richard Slater Revision 78 a PDF version of this document is available at http://www.richard-slater.co.uk/university/dissertation Page 1 of 28 What is the future of Massively Multiplayer Online Gaming? Richard Slater (00804443) 1) Table of Contents 1) Table of Contents................................................................................................... 2 2) Abstract................................................................................................................ 3 3) Introduction........................................................................................................... 4 3.1) Terms and Definitions.......................................................................................4 3.2) Quality of references........................................................................................5 -

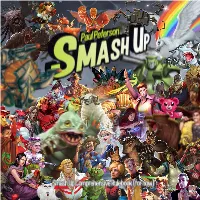

(From the Bigger Geekier Box Rulebook)!

1 The LeasT Funny smash up RuLebook eveR conTenTs Smash Up is a fght for 2–4 players, ages 14 and up. Objective ....................................................2 The Expanding Universe Game Contents...............................................2 From its frst big bang, the Smash Up universe The Expanding Universe.........................................................2 objecTive has expanded until our frst Big Geeky Box How to Use This Book............................................................2 became too small to hold it all! So we took that Know Your Cards! ............................................3 Your goal is nothing short of total global domination! box and made it better, stronger, faster, bigger. Meet These Other Cards! .....................................3 Use your minions to crush enemy bases. The frst Not only does this new box hold all the cards, Setup ........................................................4 player to score 15 victory points (VP) wins! this rulebook holds all the rules as well, or at Sample Setup ................................................4 least everything published up to now, all in one Kickin’ It Queensberry.......................................................... 4 convenient if not terribly funny 32-page package. As the Game Turns / The Phases of a Turn . 5 Game conTenTs The Big Score ................................................6 This glorious box of awesome contains: How to Use This Book Me First! ....................................................................... 6 Awarding -

Telecommunications Seminar 2007

Why peoPlE play MmorPgs Indiana University 11 th April 2007 Prof. Richard A. Bartle University of esSex introduction • This talk concerns massively multiplayer online role-playing games – Mmorpgs to the players • Or mmogs, mmos, pws, muds, mugs, mu*s, … – Virtual worlds to academics • Or synthetic worlds, virtual environments, … • My aim here is to explain Why people play them – Because, hey, then we get better ones! • Get comfy, it’s a long journey… 1 What are vws? • Virtual worlds are places • being places, they have a number of place- like features – You can visit them – Other people can also visit them – At the same time • They are, however, not real • This seems like a major disadvantage – How do you visit somewhere that isn’t real? Answer: • You use an avatar – Or, more technically speaking, a character 2 About avatars • Far from its being a disadvantage , people often like using an avatar Furthermore… • Some people prefer it to reality 3 Leisure time • People play these for several hours a day – Day after day • Month after month – Year after year… • I have players for my own game that are still there after 19 years • Surveys have consistently shown that The average time a player spends in a virtual world is around 20 hours a wEek – They often invest a lot of time in it oFfline , too • So where did these games come from? World of warcraft • world of warcraft , blizzard, 2004: 4 everquest • Everquest , sony online entertainment, 1999 connection • Everquest ruled until Wow came along – 480,000 subscriptions at its peak • Wow is modeLled -

5 Kaceytron and Transgressive Play on Twitch.Tv Mia Consalvo Kaceytron and Transgressive Play on Twitch.Tv

FOR REPOSITORY USE ONLY DO NOT DISTRIBUTE 5 Kaceytron and Transgressive Play on Twitch.tv Mia Consalvo Kaceytron and Transgressive Play on Twitch.tv Mia Consalvo © Massachusetts Institute of Technology All Rights Reserved “Fucking 4chan!” the woman on the Twitch stream exclaims in disgust. “Is that how you found my stream?!?! Were they posting fake nudes of me on 4chan?!” The Twitch stream shows an attractive young woman with glasses and a low-cut shirt on the left side of the frame; behind her and taking up the rest of the stream is her computer mon- itor’s screen—showing at center a long and narrow, blurry but rapidly scrolling text chat window that features the term CUM DUMPSTER spammed over and over again. To the right of the text barrage, a browser window is opened to a page that is difficult to read but shows some Twitch interaction rules at the top and comments below. To the right of the streaming window (not pictured in figure 5.1 ), the overflowing chat chan- nel crawls ever upward rapidly, making some comments difficult to read unless they are repeated (as many of them are) and in all caps. Someone has copy-pasted “KaceyPls THIS IS A KACEYTRON WAITING ROOM” multiple times into one comment that is nine lines long, and other chatters are rapidly posting “4chin,” echoing (and mocking) Kaceytron as she shifts from pronouncing the infamous hate-filled site “4chan” into “4chin” in her rant. After 20 seconds, the scene jumps to Kaceytron announcing, “I’m one of the best streamers on Twitch.tv but sexists won’t admit it because they’re -

Running Head: ONLINE GAMING MOTIVATIONAL FACTORS

Running Head: ONLINE GAMING MOTIVATIONAL FACTORS Motivational Factors of Online Gaming in Intermediate Elementary Students by Christopher D. Harper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION IN EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP VANCOUVER ISLAND UNIVERSITY We accept the Thesis as conforming to the required standard. Dr. Rachel Moll, Faculty Supervisor Faculty of Education, Vancouver Island University Dr. David Paterson, Dean Faculty of Education, Vancouver Island University July 2020 ONLINE GAMING MOTIVATIONAL FACTORS ii Abstract Since their introduction in the 1980s, home video game consoles have held sway over the youth of modern society. For nearly two decades, popular gaming consoles were unable to connect to online networks, relying on a system of cartridges or CDs. Near the end of the millennium, online gameplay was virtually an unknown entity, relegated to a limited number of PC games. However, over the years, companies like Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft labored relentlessly to develop innovative gaming experiences, while fueling a multi-billion-dollar industry. As a result, unintended consequences of deeply integrating online gameplay into our daily lives have emerged. One such problem affecting a growing number of adolescents is the addictive nature of modern video games and the resulting negative effects on peer relationships, self-concept, and personal and social awareness. This study focused on intermediate elementary students in SD 70 Alberni. 27 students responded to questions through an online survey to provide information about their motivations for playing online and sociodemographic factors. Two open-ended questions, “What do you enjoy most about online gaming?” and “What do you enjoy least about online gaming?”, were also included. -

Mud Connector

Archive-name: mudlist.doc /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ THE /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/ MUD CONNECTOR /_/_/ /_/_/_/_/ MUD LIST /_/_/_/_/ /_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/ o=======================================================================o The Mud Connector is (c) copyright (1994 - 96) by Andrew Cowan, an associate of GlobalMedia Design Inc. This mudlist may be reprinted as long as 1) it appears in its entirety, you may not strip out bits and pieces 2) the entire header appears with the list intact. Many thanks go out to the mud administrators who helped to make this list possible, without them there is little chance this list would exist! o=======================================================================o This list is presented strictly in alphabetical order. Each mud listing contains: The mud name, The code base used, the telnet address of the mud (unless circumstances prevent this), the homepage url (if a homepage exists) and a description submitted by a member of the mud's administration or a person approved to make the submission. All listings derived from the Mud Connector WWW site http://www.mudconnect.com/ You can contact the Mud Connector staff at [email protected]. [NOTE: This list was computer-generated, Please report bugs/typos] o=======================================================================o Last Updated: June 8th, 1997 TOTAL MUDS LISTED: 808 o=======================================================================o o=======================================================================o Muds Beginning With: A o=======================================================================o Mud : Aacena: The Fatal Promise Code Base : Envy 2.0 Telnet : mud.usacomputers.com 6969 [204.215.32.27] WWW : None Description : Aacena: The Fatal Promise: Come here if you like: Clan Wars, PKilling, Role Playing, Friendly but Fair Imms, in depth quests, Colour, Multiclassing*, Original Areas*, Tweaked up code, and MORE! *On the way in The Fatal Promise is a small mud but is growing in size and player base.