San Juan County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Steering Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Public Beach List

2021 Public Beach List - Special Rules The following is a list of popular public beaches with special rules because of resource needs and/or restrictions on harvest due to health concerns. If a beach is not listed below or on page 2, it is open for recreational harvest year-round unless closed by emergency rule, pollution or shellfish safety closures. Click for WDFW Public Beach webpages and seasons 2021 Beach Seasons adopted February 26, 2021 Open for Clams, Mussels & Oysters = Open for Oysters Only = For more information, click on beach name below to view Jan1- Jan15- Feb1- Feb15- Mar1- Mar15- Apr1- Apr15- May1- May15- Jun1- Jun15- Jul1- Jul15- Aug1- Aug15- Sep1- Sep15- Oct1- Oct15- Nov1- Nov15- Dec1- Dec15- beach-specific webpage. Jan15 Jan31 Feb15 Feb28 Mar15 Mar31 Apr15 Apr30 May15 May31 Jun15 Jun30 Jul15 Jul31 Aug15 Aug31 Sep15 Sep30 Oct15 Oct31 Nov15 Nov30 Dec15 Dec31 Ala Spit No natural production of oysters Belfair State Park Birch Bay State Park Dash Point State Park Dosewallips State Park Drayton West Duckabush Dungeness Spit/NWR Tidelands No natural production of oysters Eagle Creek Fort Flagler State Park Freeland County Park No natural production of oysters. Frye Cove County Park Hope Island State Park Illahee State Park Limited natural production of clams Indian Island County Park No natural production of oysters Kitsap Memorial State Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Kopachuck State Park Mystery Bay State Park Nahcotta Tidelands (Willapa Bay) North Bay Oak Bay County Park CLAMS AND OYSTERS CLOSED Penrose Point State Park Point -

State Park Contact Sheet Last Updated November 2016

WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION Film Permit Application State Park Contact Sheet Last Updated November 2016 AREA MANAGER PHONE PARK NAME PARK AREA ADDRESS EMAIL (@parks.wa.gov) REGION Sharon Soelter ALTA LAKE STATE PARK (509) 923-2473 Alta Lake State Park Alta Lake Area 1B OTTO ROAD [email protected] Eastern PATEROS WA 98846 Brian Hageman FORT WORDEN STATE PARK Anderson Lake (360) 344-4442 Olympic View Area 200 BATTERY WAY State Park [email protected] Southwest PORT TOWNSEND, WA 98368-3621 Chris Guidotti BATTLE GROUND STATE PARK Battle Ground Lake (360) 687-4621 Battle Ground Area PO BOX 148 State Park [email protected] Southwest HEISSON, WA 98622 Kevin Kratochvil RASAR STATE PARK (360) 757-0227 Bay View State Park Rasar Area 38730 CAPE HORN ROAD [email protected] Northwest CONCRETE, WA 98237 Chris Guidotti BATTLE GROUND STATE PARK Beacon Rock (509) 427-8265 Battle Ground Area PO BOX 148 State Park [email protected] Southwest HEISSON, WA 98622 Joel Pillers BELFAIR STATE PARK (360) 275-0668 Belfair State Park South Sound Area 3151 N.E. SR 300 [email protected] Southwest BELFAIR, WA 98528 Jack Hartt DECEPTION PASS STATE PARK Ben Ure Island Marine (360) 675-3767 Deception Pass Area 41020 STATE ROUTE 20 State Park [email protected] Northwest OAK HARBOR, WA 98277 Ted Morris BIRCH BAY STATE PARK (360) 371-2800 Birch Bay State Park Birch Bay Area 5105 HELWEG ROAD [email protected] Northwest BLAINE WA 98230 Dave Roe MANCHESTER STATE PARK Blake Island Marine (360) 731-8330 Blake -

RCFB April 2021 Page 1 Agenda TUESDAY, April 27 OPENING and MANAGEMENT REPORTS 9:00 A.M

REVISED 4/8/21 Proposed Agenda Recreation and Conservation Funding Board April 27, 2021 Online Meeting ATTENTION: Protecting the public, our partners, and our staff are of the utmost importance. Due to health concerns with the novel coronavirus this meeting will be held online. The public is encouraged to participate online and will be given opportunities to comment, as noted below. If you wish to participate online, please click the link below to register and follow the instructions in advance of the meeting. Technical support for the meeting will be provided by RCO’s board liaison who can be reached at [email protected]. Registration Link: https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_JqkQAGCrRSOwbHLmg3a6oA Phone Option: (669)900-6833 - Webinar ID: 967 5491 2108 Location: RCO will also have a public meeting location for members of the public to listen via phone as required by the Open Public Meeting Act, unless this requirement is waived by gubernatorial executive order. In order to enter the building, the public must not exhibit symptoms of the COVID-19 and will be required to comply with current state law around personal protective equipment. RCO staff will meet the public in front of the main entrance to the natural resources building and escort them in. *Additionally, RCO will record this meeting and would be happy to assist you after the meeting to gain access to the information. Order of Presentation: In general, each agenda item will include a short staff presentation and followed by board discussion. The board only makes decisions following the public comment portion of the agenda decision item. -

Lime Kiln Point State Park (San Juan Island)

Ranald MacDonald’s Grave Your guide to state parks in the Auto-accessible parks Auto-accessible parks Lime Kiln Point State Park Moran State Park Spencer Spit State Park Obstruction Pass State Park Welcome (San Juan Island) (Orcas Island) (Lopez Island) (Orcas Island) San Juan The San Juan archipelago north of Puget At Lime Kiln Point State Park, the loud neighbors Pass through the welcome arch at Moran State Spencer Spit on Lopez Island provides dramatic Obstruction Pass State Park is one of the few Sound is like no other place on earth. The cluster gear up for a party that runs from spring into Park, and time begins to slow. You’ll find yourself views of Decatur and Blakely islands and Mount public beaches on famed Orcas Island. of 400 islands and rocks in the Salish Sea is a fall. Those would be the spouting Orcas, fin- in a Northwest island frame of mind, free to relax, Constitution on Orcas Island, and it features a Though most people flock to its bigger world unto itself. It is a world where people are slapping gray whales, barking sea lions and breathe and head into the vast, varied terrain. rare sand spit enclosed by a salt-chuck lagoon. neighbor, Moran State Park, this property’s friendly and hearty, where the land smells like splashing porpoises. Hike, cycle or drive to the summit of Mount The effect is a driftwood-scattered beach on quiet beauty is unsurpassed. Clear waters lap at the sea, and wind, art and history are celebrated. Constitution for expansive views of the San Juan one side of the spit and a spongy marsh on the pebbly beaches, and madrone trees cling to Obstruction Pass Islands For island dwellers and visitors, the pace of life other. -

Migratory Bird

-o a o — z -n c: ST! <g»S z Ra 1 »•£ = =H H> - 2 » 2 "> -< r- cu o =: Z ,—. National Wildlife Refuges of s The "Migratory Bird" Refuges -n DO "_- ""= = „ = = S=> zs: oo = c« J> -n o, « —I -o ac to s> SS; i— 3» Dungeness National Wildlife 2 m o)2 2 a H Puget Sound <= a. — c/3 m Refuge oo a. m -TO OO a, _ DO and What Are Migratory Birds? Why Do They Come Here? Dungeness Spit is formed by eroding soil, wind, and water C3 CD j3£ currents, and stretches for five and one-half miles along the = m While some birds live in one area year-round, "migratory Like people, migratory birds need food, water and shelter. Strait of Juan de Fuca. It breaks the rough sea waves to <=> Coastal Washington birds" make regular seasonal flights from one area to Both Nisqually and Dungeness National Wildlife Refuges form a quiet bay, sand and gravel beaches, and tideflats -n another. These birds usually fly between wintering areas and have abundant supplies of water and offer a smorgasbord of —I where wildlife can find food and protection from wind, m summer breeding grounds. Although many species go north foods to suit a variety of avian tastes. Shorebirds may feast on waves, and pounding surf. The bay and estuary of the and south, others travel between coastal breeding areas and mudflat invertebrates while goldfinches prefer the fluffy Dungeness River produce micro-organisms that form the —I the open sea. Migration allows them to escape the short days m seeds of thistles and dandelions. -

Washington State's Scenic Byways & Road Trips

waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS inSide: Road Maps & Scenic drives planning tips points of interest 2 taBLe of contentS waShington State’S Scenic BywayS & Road tRipS introduction 3 Washington State’s Scenic Byways & Road Trips guide has been made possible State Map overview of Scenic Byways 4 through funding from the Federal Highway Administration’s National Scenic Byways Program, Washington State Department of Transportation and aLL aMeRican RoadS Washington State Tourism. waShington State depaRtMent of coMMeRce Chinook Pass Scenic Byway 9 director, Rogers Weed International Selkirk Loop 15 waShington State touRiSM executive director, Marsha Massey nationaL Scenic BywayS Marketing Manager, Betsy Gabel product development Manager, Michelle Campbell Coulee Corridor 21 waShington State depaRtMent of tRanSpoRtation Mountains to Sound Greenway 25 Secretary of transportation, Paula Hammond director, highways and Local programs, Kathleen Davis Stevens Pass Greenway 29 Scenic Byways coordinator, Ed Spilker Strait of Juan de Fuca - Highway 112 33 Byway leaders and an interagency advisory group with representatives from the White Pass Scenic Byway 37 Washington State Department of Transportation, Washington State Department of Agriculture, Washington State Department of Fish & Wildlife, Washington State Tourism, Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and State Scenic BywayS Audubon Washington were also instrumental in the creation of this guide. Cape Flattery Tribal Scenic Byway 40 puBLiShing SeRviceS pRovided By deStination -

A Model for Measuring the Benefits of State Parks for the Washington State Parks And

6 A Model for Measuring the Benefits of State Parks for the Washington State Parks and january 201 january Recreation Commission Prepared By: Prepared For: Earth Economics Washington State Parks and Tacoma, Washington Recreation Commission Olympia, Washington Primary Authors: Tania Briceno, PhD, Ecological Economist, Earth Economics Johnny Mojica, Research Analyst, Earth Economics Suggested Citation: Briceno, T., Mojica, J. 2016. Statewide Land Acquisition and New Park Development Strategy. Earth Economics, Tacoma, WA. Acknowledgements: Thanks to all who supported this project including the Earth Economics team: Greg Schundler (GIS analysis), Corrine Armistead (Research, Analysis, and GIS), Jessica Hanson (editor), Josh Reyneveld (managing director), Sage McElroy (design); the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission: Tom Oliva, Katie Manning, Steve Hahn, Steve Brand, Nikki Fields, Peter Herzog and others. We would also like to thank our Board of Directors for their continued guidance and support: Ingrid Rasch, David Cosman, Sherry Richardson, David Batker, and Joshua Farley. The authors are responsible for the content of this report. Cover image: Washington State Department of Transportation ©2016 by Earth Economics. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Executive Summary Washington’s state parks provide a myriad of benefits to both urban and rural environments and nearby residents. Green spaces within state parks provide direct benefits to the populations living in close proximity. For example, the forests within state parks provide outdoor recreational opportunities, and they also help to store water and control flooding during heavy rainfalls, improve air quality, and regulate the local climate. -

© Copyright 2019 Rochelle M. Kelly

© Copyright 2019 Rochelle M. Kelly Diversity, distributions, and activity of bats in the San Juan Islands Rochelle M. Kelly A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Sharlene E. Santana, Chair Adam D. Leaché Cori Lausen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Biology University of Washington Abstract Diversity, distributions, and activity of bats in the San Juan Islands Rochelle M. Kelly Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Sharlene E. Santana Biology The loss and fragmentation of natural habitats are some of the greatest threats to terrestrial biodiversity. Much of the practice of conservation science is rooted in Island Biogeography Theory (IBT). IBT postulates that species richness on islands is driven by a dynamic equilibrium between the effects of area on extinction rates and the effects of isolation on colonization rates. However, studies of plants and animals on oceanic islands and man-made habitat islands suggest that IBT needs to be broadened to consider additional habitat characteristics beyond area and isolation. Additionally, species-specific differences in ecology, life-history, morphology, and mobility are all implicated to mediate how species respond to habitat fragmentation. In Chapter one, I investigated how island area, isolation, and habitat quality influence species richness in a naturally fragmented landscape - The San Juan Archipelago. I also examined whether ecological traits or morphological traits associated with mobility mediate species-specific distribution and activity patterns on the islands. I found that species richness increased on larger islands, but was not affected by habitat quality or isolation at this scale. -

National List of Beaches 2004 (PDF)

National List of Beaches March 2004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington DC 20460 EPA-823-R-04-004 i Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 States Alabama ............................................................................................................... 3 Alaska................................................................................................................... 6 California .............................................................................................................. 9 Connecticut .......................................................................................................... 17 Delaware .............................................................................................................. 21 Florida .................................................................................................................. 22 Georgia................................................................................................................. 36 Hawaii................................................................................................................... 38 Illinois ................................................................................................................... 45 Indiana.................................................................................................................. 47 Louisiana -

25 JUL 2021 Index Aaron Creek 17385 179 Aaron Island

26 SEP 2021 Index 401 Angoon 17339 �� � � � � � � � � � 287 Baranof Island 17320 � � � � � � � 307 Anguilla Bay 17404 �� � � � � � � � 212 Barbara Rock 17431 � � � � � � � 192 Index Anguilla Island 17404 �� � � � � � � 212 Bare Island 17316 � � � � � � � � 296 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Ser- Bar Harbor 17430 � � � � � � � � 134 vice � � � � � � � � � � � � 24 Barlow Cove 17316 �� � � � � � � � 272 Animas Island 17406 � � � � � � � 208 Barlow Islands 17316 �� � � � � � � 272 A Anita Bay 17382 � � � � � � � � � 179 Barlow Point 17316 � � � � � � � � 272 Anita Point 17382 � � � � � � � � 179 Barnacle Rock 17401 � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Creek 17385 �� � � � � � � � 179 Annette Bay 17428 � � � � � � � � 160 Barnes Lake 17382 �� � � � � � � � 172 Aaron Island 17316 �� � � � � � � � 273 Annette Island 17434 � � � � � � � 157 Baron Island 17420 �� � � � � � � � 122 Aats Bay 17402� � � � � � � � � � 277 Annette Point 17434 � � � � � � � 156 Bar Point Basin 17430� � � � � � � 134 Aats Point 17402 �� � � � � � � � � 277 Annex Creek Power Station 17315 �� � 263 Barren Island 17434 � � � � � � � 122 Abbess Island 17405 � � � � � � � 203 Appleton Cove 17338 � � � � � � � 332 Barren Island Light 17434 �� � � � � 122 Abraham Islands 17382 � � � � � � 171 Approach Point 17426 � � � � � � � 162 Barrie Island 17360 � � � � � � � � 230 Abrejo Rocks 17406 � � � � � � � � 208 Aranzazu Point 17420 � � � � � � � 122 Barrier Islands 17386, 17387 �� � � � 228 Adams Anchorage 17316 � � � � � � 272 Arboles Islet 17406 �� � � � � � � � 207 Barrier Islands 17433 -

CPB7 C12 WEB.Pdf

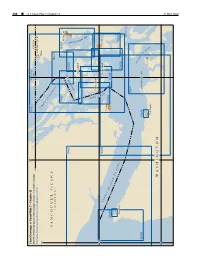

488 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 Chapter 7, Pilot Coast U.S. 124° 123° Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 7—Chapter 12 18421 BOUNDARY NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage BAY CANADA 49° http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml UNITED STATES S T R Blaine 125° A I T O F G E O R V ANCOUVER ISLAND G (CANADA) I A 18431 18432 18424 Bellingham A S S Y P B 18460 A R 18430 E N D L U L O I B N G Orcas Island H A M B A Y H A R O San Juan Island S T 48°30' R A S I Lopez Island Anacortes T 18465 T R A I Victoria T O F 18433 18484 J 18434 U A N D E F U C Neah Bay A 18427 18429 SKAGIT BAY 18471 A D M I R A L DUNGENESS BAY T 18485 18468 Y I N Port Townsend L E T Port Angeles W ASHINGTON 48° 31 MAY 2020 31 MAY 31 MAY 2020 U.S. Coast Pilot 7, Chapter 12 ¢ 489 Strait of Juan De Fuca and Georgia, Washington (1) thick weather, because of strong and irregular currents, ENC - extreme caution and vigilance must be exercised. Chart - 18400 Navigators not familiar with these waters should take a pilot. (2) This chapter includes the Strait of Juan de Fuca, (7) Sequim Bay, Port Discovery, the San Juan Islands and COLREGS Demarcation Lines its various passages and straits, Deception Pass, Fidalgo (8) The International Regulations for Preventing Island, Skagit and Similk Bays, Swinomish Channel, Collisions at Sea, 1972 (72 COLREGS) apply on all the Fidalgo, Padilla, and Bellingham Bays, Lummi Bay, waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Haro Strait, and Strait Semiahmoo Bay and Drayton Harbor and the Strait of of Georgia. -

The Totem Line 53 Years of Yachting - 54 Years of Friendship

Volume 55 Issue 3 Our 55th Year March 2010 The Totem Line 53 years of yachting - 54 years of friendship In this issue…Annual awards announced; Membership drive emphasis; Consider WA marine parks Upcoming Events Commodore.………………...….…. Ray Sharpe [email protected] Mar 2…………..…………...…General Meeting Mar 6………... Des Moines Commodore’s Ball Vice Commodore…………… Gene Mossberger Mar 16…………...…………..… Board Meeting [email protected] Mar 17…………….NBC Meeting at Totem YC Mar 18 – 21..….…………Anacortes Boat Show Rear Commodore…….…………….Bill Sheehy Mar 19 – 21.….……………Coming Out Cruise [email protected] Mar 27………....…….………….....Spring Fling C ommodore’s Report The Membership Yearbook is Area Fuel Prices going to print shortly and should http://fineedge.com/fuelsurvey.html be ready for the March general Updated 1/27/10 meeting. Thanks to Gene, Dan and Mary for their efforts. C ommodore (Cont’d) by itself. If there isn’t some one willing to take on I want to thank Gene and Patti the organizing of this event and make it a great end of Mossberger, Bill and Val summer happening, then we need to decide now so Sheehy, and Rocci and Sharon Blair for attending the club can let Fair Harbor know that we’re not The TOA Commodores Ball with Char and myself going to do it. Then they can have it available to other and supporting Totem Yacht Club. boaters that may want it. Last year was a last minute scramble by some dedicated members. It is a lot Val Sheehy has stepped forward to take on the easier if it is done with proper planning.