In Re International Tractors Ltd. _____

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2008

University of San Diego Digital USD Baseball (Men) University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides Spring 2008 University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2008 University of San Diego Athletics Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-baseball Digital USD Citation University of San Diego Athletics Department, "University of San Diego Baseball Media Guide 2008" (2008). Baseball (Men). 25. https://digital.sandiego.edu/amg-baseball/25 This Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the University of San Diego Athletics Media Guides at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Baseball (Men) by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AGENERAL INFORMATION Location .................................................................................................. San Diego, CA ..._ PHOTO .CRE.DENTIALS J! . Founded ..................... ................................... .. .......................................................... 1949 Credentials will be issued on a game-by-game baSIS and must be worn In plain sig ht at Enrollment ....... ................................... ..................................................................... 7,600 all times. All photographers must remain off the playing su rface and are encouraged President ........................................................................................ Mary E. Lyons, Ph.D. to use the area behind the visitors' dugout. NCAA regulations regarding -

2013 AFL Game Notes

2013 AFL Game Notes Saturday, October 19, 2013 Media Relations: Paul Jensen (480) 710-8201, [email protected] Dylan Higgins (509) 540-4034, [email protected] Nate Rowan (651) 983-5605, [email protected] Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague Facebook: www.facebook.com/mlbfallball East Division Probable Starters Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Mesa Solar Sox 7 1 .875 -- 3-1 4-0 3-0 L1 7-1 Salt River Rafters 3 6 .333 4.5 1-5 2-1 1-2 W1 3-6 Saturday, October 19 Scottsdale Scorpions 3 6 .333 4.5 2-3 1-3 1-3 W1 3-6 Scottsdale at *Peoria, 12:35 PM (L) West Division LHP Vidal Nuno (0-1, 6.75 ERA) @ Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 LHP Kyle Hunter (0-1, 3.60 ERA) Glendale Desert Dogs 5 3 .625 -- 3-0 2-3 2-1 L1 5-3 Surprise at Glendale, 6:35 PM (A) Surprise Saguaros 5 4 .556 0.5 2-2 3-2 2-1 W2 5-4 LHP Tim Berry (0-0, 6.00 ERA) @ Peoria Javelinas 3 6 .333 2.5 2-2 1-4 1-3 L3 3-6 RHP Trevor May (0-0, 3.00 ERA) Salt River at Mesa, 6:35 PM (F) RHP Drew Hutchison (0-0, 0.00 ERA) @ Yesterday’s Games LHP Michael Roth (1-0, 7.71 ERA) R H E LOB Sunday, October 20 Surprise 11 17 1 9 W: Goforth (MIL) (1-0) L: Rivero (CHC) (0-1) League off day Mesa 9 12 1 10 S: Couch (BOS) (1) Monday, October 21 Saguaros: 1B Travis Shaw (BOS) 1-for-4, 3-run HR (3) in 4th, 4 RBI … DH Henry Urrutia (BAL) 3-for- Surprise at Mesa, 12:35 PM (A) 4, 2 2Bs, RBI, R, SB … CF Tyler Naquin (CLE) 3-for-5, RBI, R, SB. -

A's News Clips, Wednesday, November 9, 2011

A’s News Clips, Friday, November 11, 2011 A's make adjustments to Minor League staff Steverson, Sparks among those moving to new positions By Jane Lee / MLB.com OAKLAND -- Plenty of change was quickly seen in the A's coaching staff following the end of the season, and more of the same is reflected throughout the organization's farm system. The A's announced several modifications to their Minor League staff assignments for the 2012 season on Thursday, most notably Todd Steverson's move to roving Minor League hitting instructor. The former A's first-base coach replaces Greg Sparks, who slides into Steverson's old job as hitting coach for Triple-A Sacramento. A handful of pitching coaches were also shuffled, with John Wasdin going to Class A Burlington and Ariel Prieto moving to Class A Vermont, while Jimmy Escalante was named pitching coach of the A's affiliate in the Arizona Rookie League. Meanwhile, all six managers of Oakland's affiliates are set to return in the same capacity next season. It will mark Triple-A manager Darren Bush's second season at the helm in Sacramento, where he'll again be joined by pitching coach Scott Emerson. Bush guided the River Cats to an 88-56 record and a playoff appearance this year. Steve Scarsone will return to manage at Double-A Midland for the second consecutive season, with a staff that consists of pitching coach Don Schulze and hitting coach Tim Garland. Webster Garrison will manage his second season with Class A-Advanced Stockton, after the Ports enjoyed an appearance in the California League playoffs this year. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings July 14, 2017 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1970-Riverfront Stadium hosts the All-Star Game and the National League wins, 5-4, in 12 innings. President Richard Nixon throws out the first pitch prior to the All-Star Game, but what the game is most remembered for is Pete Rose crashing into American League catcher, Ray Fosse, to score the winning run on Jim Hickman’s RBI-single MLB.COM Adleman starts vs. Nats to begin 2nd half By Kyle Melnick / MLB.com | 9:43 AM ET + 37 COMMENTS The Nationals displayed one of the most potent offenses the first half of the season, leading the National League in almost every offensive category. Bryce Harper, Ryan Zimmerman and Daniel Murphy -- the middle of the lineup -- led that charge with three of the Top 5 batting averages in the NL. Washington will look to continue that offensive production in the second half as their five All-Stars return Friday night to begin a four-game set against the Reds at Great American Ball Park. The Nats took two out of three from Cincinnati when the teams met in June, but Zack Cozart, one the Reds' two All-Stars, didn't play due to a quadriceps injury. The teams are on opposite ends of the spectrum in their respective divisions. The Nationals are looking to maintain their sizeable lead in the NL East, while the Reds enter the second half fighting to get out of last place in the NL Central. Cincinnati will start Tim Adleman, while Washington will send left-hander Gio Gonzalez to the mound. -

2013 AFL Game Notes

2013 AFL Game Notes Tuesday, October 22, 2013 Media Relations: Paul Jensen (480) 710-8201, [email protected] Dylan Higgins (509) 540-4034, [email protected] Nate Rowan (651) 983-5605, [email protected] Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague Facebook: www.facebook.com/mlbfallball East Division Probable Starters Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Mesa Solar Sox 8 2 .800 -- 4-2 4-0 3-1 W1 8-2 Tuesday, October 22 Scottsdale Scorpions 5 6 .455 3.5 3-3 2-3 1-3 W3 4-6 Mesa at Surprise, 12:35 PM (L) Salt River Rafters 4 7 .364 4.5 1-5 3-2 2-2 L1 4-6 RHP Tommy Collier (0-0, 1.80 ERA) @ LHP Eduardo Rodriguez (0-0, 4.76 ERA) West Division Scottsdale at Glendale, 12:35 PM (A) Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 RHP Kyle Crick (0-1, 7.20 ERA) @ Surprise Saguaros 6 5 .545 -- 2-2 4-3 3-1 L1 5-5 LHP Andrew Heaney (1-0, 2.70 ERA) Glendale Desert Dogs 5 5 .500 0.5 3-1 2-4 2-2 L3 5-5 Peoria at Salt River, 6:35 PM (F) Peoria Javelinas 4 7 .364 2.0 3-3 1-4 1-3 W1 4-6 LHP Alex Sogard (1-1, 3.86 ERA) @ LHP Grayson Garvin (1-1, 3.00 ERA) Yesterday’s Games Wednesday, October 23 Salt River at Surprise, 12:35 PM (F) R H E LOB RHP Aaron Sanchez (0-1, 3.60 ERA) @ Salt River 3 5 1 4 W: O’Grady (SD) (1-0) L: Matzek (COL) (0-1) RHP Will Roberts (0-1, 2.57 ERA) Peoria 5 9 1 7 S: Leone (SEA) (2) Peoria at Glendale, 12:35 PM (L) Javelinas: CF Delino DeShields (HOU) 3-for-4, 2 2B, R … 1B Japhet Amador (HOU) 1-for-4, 2-run RHP Johnny Barbato (0-1, 7.36 ERA) @ HR (2) in 7th … C Austin Hedges (SD) 1-for-3, 3B, RBI, R. -

2013 AFL Game Notes

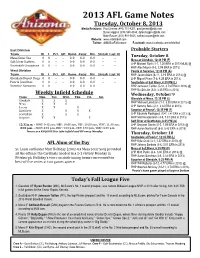

2013 AFL Game Notes Tuesday, October 8, 2013 Media Relations: Paul Jensen (480) 710-8201, [email protected] Dylan Higgins (509) 540-4034, [email protected] Nate Rowan (651) 983-5605, [email protected] Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague Facebook: www.facebook.com/mlbfallball East Division Probable Starters Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Tuesday, October 8 Mesa Solar Sox 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- Mesa at Glendale, 12:35 PM (F) Salt River Rafters 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- LHP Michael Roth (1-1, 7.20 ERA in 2013 MLB) @ Scottsdale Scorpions 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- RHP Alex Meyer (4-3, 2.99 ERA in 2013) West Division Peoria at Surprise, 12:35 PM (A) Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 RHP Jason Adam (8-11, 5.19 ERA in 2013) @ Glendale Desert Dogs 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- LHP Miguel Pena (7-8, 4.29 ERA in 2013) Peoria Javelinas 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- Scottsdale at Salt River, 6:35 PM (L) Surprise Saguaros 0 0 -- -- 0-0 0-0 0-0 -- -- RHP Jameson Taillon (5-10, 3.73 ERA in 2013) @ RHP Bo Schultz (5-6, 3.35 ERA in 2013) Weekly Infield Schedule Wednesday, October 9 Team Mon. Tue. Wed. Thu. Fri. Sat. Glendale at Mesa, 12:35 PM (L) Glendale X X X RHP Michael Lorenzen (1-1, 3.00 ERA in 2013) @ Mesa X X X Peoria X X X LHP Sammy Solis (2-1, 3.32 ERA in 2013) Salt River X X X X Surprise at Peoria*, 12:35 PM (F) Scottsdale X X X LHP Eduardo Rodriguez (10-7, 3.41 ERA in 2013) @ Surprise X X X RHP Matt Heidenreich (4-5, 7.81 ERA in 2013) Salt River at Scottsdale, 6:35 PM (A) 12:35 p.m. -

2011 AFL Game Notes

2011 AFL Game Notes Thursday, October 6, 2011 Media Relations: Paul Jensen (480) 710-8201, [email protected] Rob Morse (541) 556-9387, [email protected] Patrick Kurish (480) 628-4446, [email protected] Media Relations FAX: (602) 681-9363 Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague East Division Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Probable Starters Salt River Rafters 1 1 .500 - 0-1 1-0 0-0 L1 1-1 Thursday, October 6, 2011 Scottsdale Scorpions 0 1 .000 0.5 0-0 0-1 0-0 L1 0-1 Scottsdale at Salt River, 12:35 PM (A) Mesa Solar Sox 0 2 .000 1.0 0-1 0-1 0-0 L2 0-2 51 LHP Sammy Solis (WSH) @ West Division 67 LHP Andy Oliver (DET) Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Surprise at Mesa, 12:35 PM (F) Phoenix Desert Dogs 2 0 1.000 - 1-0 1-0 0-0 W2 2-0 2 LHP Sean Gilmartin (ATL) @ Surprise Saguaros 1 0 1.000 0.5 1-0 0-0 0-0 W1 1-0 48 RHP Steve Johnson (BAL) Peoria Javelinas 1 1 .500 1.0 0-1 1-0 0-0 W1 1-1 Phoenix at Peoria, 6:35 PM (L) 37 LHP T.J. McFarland (CLE) @ Yesterday’s Games 34 RHP Tyler Lyons (STL) R H E LOB Friday, October 7, 2011 Scorpions 1 2 0 2 W: Dyer (TB) (1-0) L: Huntzinger (BOS) (0-1) Mesa at Salt River, 12:35 PM (L) Saguaros 10 14 1 7 S: None 44 RHP Trey McNutt (CHC) @ 43 LHP Dallas Keuchel (HOU) Saguaros RHP Shane Dyer (TB) (3.0 IP) and five relievers combined on two-hitter .. -

Washington Nationals 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 5 11 0 4

l POST-GAME NOTES – SUNDAY, MAY 10, 2015 NATIONALS 5, BRAVES 4 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E LOB Atlanta Braves 0 2 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 4 12 0 10 Washington Nationals 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 5 11 0 4 Winning Pitcher: Sammy Solis (1-0) Home Runs (Season Total, Inning off Pitcher, Runners On , Outs, Count) Losing Pitcher: Cody Martin (1-2) ATL : None Save: Drew Storen (9) WSH: None Starters’ Pitch Count Pitches Strikes Alex Wood 100 67 Jordan Zimmermann 107 65 First Pitch: 1:36 p.m. GameTime Temp.: 80 degrees Time of Game: 2 hours, 51 minutes Attendance: 31,938 WASHINGTON NATIONALS (17-15) -C Wilson Ramos plated 1B Ryan Zimmerman with an RBI-double to right field in the eighth inning to put the Nationals ahead, for good…With today’s 5-4 win, Washington claimed its first series sweep of the season…With the win, the Nationals have now won five in a row over the Braves and 10 of their last 12 games overall. -1B Ryan Zimmerman went 2-for-4 with a double, two RBI and two runs scored…His RBI-double in the first inning plated RF Bryce Harper …He would come around to score on a single by C Wilson Ramos ...He then tied the game in the bottom of the eight with an RBI-single to center, scoring SS Ian Desmond …With today’s effort, Zimmerman has now hit safely in 11 of his last 13 games. -

Los Angeles Dodgers (1-0) at Washington Nationals (0-1)

Los Angeles Dodgers (1-0) at Washington Nationals (0-1) LHP Rich Hill [12-5, 2.12] | RHP Tanner Roark [16-10, 2.83] Sunday, October 9 l Game #2 / NLDS l Nationals Park l Washington, D.C. l 1:08 P.M. Television: FS1 l Radio: 106.7 The Fan & Nationals Radio Network Standing: 95-67, 1st place, National League East • Home: 50-31 • Road: 45-36 • Streak: W2 • Last Five: 3-2 • Last Ten: 6-4 NATIONALS NEWS OPPONENT LOS ANGELES DODGERS The Nationals and Dodgers opened the first-ever playoff series between the two clubs on Friday, Oct. 7 at Nationals Park...The Dodgers and Montreal Expos met once in the Post- season, in the 1981 National League Championship Series -- which LAD won, 3-2, with help from several familiar faces...The ties between the Nationals and Dodgers run deep, starting with Nationals manager Dusty Baker, who played for LA for eight seasons (1976-1983)... HELLO, OCTOBER Baker was a two-time All-Star, two-time Silver Slugger, and a Gold Glove outfielder for the In the 12th season since baseball returned to Washington, D.C., the Washington Nationals Dodgers, hitting .281 in 1,117 games with 144 home runs, 179 doubles, and 586 RBI, and an were crowned National League East champions for the third time in the last five years...The integral part of the aforementioned 1981 World Series Championship team...Joining him on 2016 Nationals did so with an average of 15.8 wins per month and a 95-67 (.586) final regular- that team was Nationals first base coachDavey Lopes, who played for LAD from 1972-1981, season record, the second-best mark in the NL (Cubs: 103-58, .640) and tied with the Texas was a four-time All-Star and a Gold Glover, and his 418 stolen bases rank second all-time Rangers for the second-best record in Major League Baseball...Since 2012, Washington’s in Dodgers history...Hall-of-Fame voice of the Dodgers, Vin Scully, began his broadcasting three division titles are tied for the second-most in MLB behind the Los Angeles Dodgers (5). -

Harper Y Scherzer Ponen a La Capital a Soñar Con La Gloria

218 WASHINGTON NATIONALS (NL EAST) (NL EAST) WASHINGTON NATIONALS 219 MLB MLB WASHINGTON LOS PRONÓSTICOS DEL SANEDRÍN DE @MLB_AS GAME DIVISIÓN CAMPEONATO PLAYOFFS DE DE MUNDIALES DE CARD AMPEÓN SERIES SERIES WILD FUERA C SERIES NATIONALS FERNANDO DÍAZ X X X X X X PEPE RODRÍGUEZ X X X X X X LEÓN FELIPE GIRÓN X X X X X X HARPER Y SCHERZER PONEN A LA DANI GARCÍA X X X X X X CARLOS SAIZ X X X X X X CARLOS COELLO X X X X X X EDUARDO DE PAZ X X X X X X CAPITAL A SOÑAR CON LA GLORIA ANGEL LLUIS CARRILLO X X X X X X PEPE LATORRE X X X X X X Washington busca CARLOS PARRA X X X X X X frenar la tendencia LAS TRES CLAVES DEL EQUIPO l inicio de la temporada de alternar nea. En 2017 se resolverá el para- A2016, el MVP reinante apariciones en digma de si un buen catcher hacer Bryce Harper. En Washington todo empieza y ter- Bryce Harper prometió “Hacer que playoffs durante los a un buen lanzador o viceversa. mina con Harper. El ganador del MVP de la Liga el béisbol vuelva a ser divertido”. Es justo decir que en cuestiones 1 Nacional en 2015 tuvo un año a la baja en 2016 Como es costumbre en una fran- últimos seis años. de pitcheo abridor, no parecen te- y los Nationals necesitan que ‘Mondo’ vuelva a quicia carente de éxitos, no cumplió Con todo el talento ner flaquezas que impidan que la ser uno de los peloteros más temibles del pla- con su promesa. -

2019 Hagerstown Suns Media Guide Hagerstown Suns Staff Mailing/Office Address: 274 E

2019 Hagerstown Suns Media Guide Hagerstown Suns Staff Mailing/Office Address: 274 E. Memorial Blvd. Hagerstown, MD 21740 Table of Contents Phone: (301) 791-6266 Fax: (301) 791-6066 Website: hagerstownsuns.com Hagerstown Suns Staff........................................................................2 Class-A Affiliate of the Washington Nationals since 2007 Municipal Stadium Information.....................................................3 Owned and Operated by....................................................Bruce Quinn Municipal Stadium Ground Rules..................................................4 Media Policies and Information.....................................................5 Pre-game Schedule..............................................................................6 Front Office Staff Washington Nationals Top 10 Prospects..................................6 General Manager Washington Nationals Affiliates....................................................6 Travis Painter Hagerstown Media Outlets................................................................7 Assistant General Manager & Head Groundskeeper Suns Field Staff........................................................................................9 Brian Saddler Suns Player Profiles............................................................................12 Promotions & Community Relations Manager, In-Game Host Washington Nationals 2018 Draft Summary.........................19 Tom Burtman 2018 Suns Season Recap.................................................................21 -

2013 AFL Game Notes

2013 AFL Game Notes Friday, November 8, 2013 Media Relations: Paul Jensen (480) 710-8201, [email protected] Dylan Higgins (509) 540-4034, [email protected] Nate Rowan (651) 983-5605, [email protected] Website: www.mlbfallball.com Twitter: @MLBazFallLeague Facebook: www.facebook.com/mlbfallball East Division Probable Starters Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 Mesa Solar Sox 13 11 .542 -- 7-6 6-5 7-5 L3 3-7 Salt River Rafters 13 12 .520 0.5 7-6 6-6 6-4 W1 7-3 Friday, November 8 Scottsdale Scorpions 10 15 .400 3.5 6-6 4-9 3-7 L1 3-7 Surprise at Mesa, 12:35 PM (L) West Division LHP Eduardo Rodriguez (0-0, 4.63 ERA) @ Team W L Pct. GB Home Away Div. Streak Last 10 LHP Sammy Solis (3-2, 2.29 ERA) Surprise Saguaros 16 8 .667 -- 8-3 8-5 7-2 W1 8-2 Salt River at Peoria, 12:35 PM (F) Glendale Desert Dogs 11 12 .478 4.5 6-5 5-7 5-6 W2 4-6 RHP Aaron Sanchez (0-1, 1.35 ERA) @ Peoria Javelinas 10 15 .417 6.5 4-9 6-6 3-7 L1 5-5 RHP Jason Adam (1-1, 4.50 ERA) +Glendale at Scottsdale, 7:08 PM (A) RHP Alex Meyer (2-0, 3.63 ERA) @ Yesterday’s Games RHP Kyle Crick (0-1, 4.66 ERA) R H E LOB Mesa 4 5 1 4 W: Rogers (CIN) (1-0) L: Loosen (CHC) (1-1) Saturday, November 9 Glendale 5 9 0 6 Final/11 innings Mesa at Surprise, 12:35 PM (L) LHP Matt Purke (2-1, 3.79 ERA) @ Desert Dogs: SP James Walczak (CIN) 5.0 IP, 0 H, 0 R, 1 BB, 4 SO … 1B Travis Mattair (CIN) walk- LHP Will Roberts (0-1, 5.31 ERA) off single in 11th … CF Yorman Rodriguez (CIN) 2-for-5, RBI, R, SB.