Missing Medea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TWO RADIO DRAMAS of LOVE, HATE and REVENGE 1. Introduction

doi: 10.19090/i.2018.29.176-191 UDC: 821.14'02-2 ISTRAŽIVANJA ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL RESEARCHES Received: 13 March 2018 29 (2018) Accepted: 9 July 2018 GORDAN MARIČIĆ University of Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy, Department of Classics [email protected] IFIGENIJA RADULOVIĆ University of Novi Sad Faculty of Philosophy, Department of History [email protected] JELENA TODOROVIĆ University of Belgrade Faculty of Philosophy, Department of History [email protected] TWO RADIO DRAMAS OF LOVE, HATE AND REVENGE Abstract: The topic of this paper is an ancient and everlasting story of love, hate, and vengeance. This archetypal narrative was recreated and staged in the 1960s in the form of two radio dramas by two Serbian (at the time Yugoslav) playwrights Jovan Hristić and Velimir Lukić. By means of those plays the two renowned scholars and playwrights achieved the revival of the previously mentioned ancient myth in the contemporary circumstances and rewrote the old story using modern features and language. Keywords: ancient myth, love, hate, revenge, radio drama, Orestes, Medea. 1. Introduction ovan Hristić (b. 1933, d. 2002) and Velimir Lukić (b. 1936, d. 1997) are distinct drama representatives belonging to the well-known group of Serbian playwrights with a Jcharacteristic reflexive-poetic orientation, who emerged in the 1960s and enriched Serbian dramatic literature with a new approach to the world based on the relocation of the ancient myths in the contemporary reality and on the rational analysis of the burning social and moral issues of their times. At the time Yugoslavia was already open to the West and 176 published literary works which appeared to be radically detached from the doctrine of Socialist Realism. -

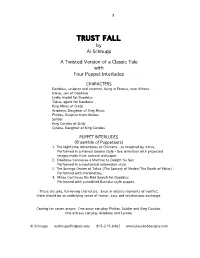

TRUST FALL by Al Schnupp

1 TRUST FALL by Al Schnupp A Twisted Version of a Classic Tale with Four Puppet Interludes CHARACTERS Daedalus, sculptor and inventor, living in Piraeus, near Athens Icarus, son of Daedalus Lydia, model for Daedalus Takus, agent for Daedalus King Minos of Crete Ariadene, Daughter of King Minos Phidias, Sculptor from Athens Soldier King Cocalos of Sicily Cyrene, Daughter of King Cocalos PUPPET INTERLUDES (Ensemble of Puppeteers) 1. The Nighttime Adventures of Chickens - as Imagined by Icarus Performed in a manual cinema style – live animation with projected images made from acetate and paper. 2. Daedalus Conceives a Machine to Delight his Son Performed in a mechanical automaton style 3. The Strange Dream of Takus (The Sorcery of Medea/The Death of Pelias) Performed with marionettes. 4. Minos Continues His Mad Search for Daedalus Performed with a modified Bunraku-style puppet. These are jolly, fun-loving characters. Even in intense moments of conflict, there should be an underlying sense of humor, sass and mischievous exchange. Casting for seven actors: One actor can play Phidias, Soldier and King Cocalos. One actress can play Ariadene and Cyrene. Al Schnupp [email protected] 805-215-6462 www.playsanddesigns.com 2 SCENE ONE THE STUDIO OF DAEDALUS (LYDIA, a scantly-clad model in her early thirties, holds a pose as DAEDALUS , in his late thirties, hammers away at his stone sculpture. A long moment passes). LYDIA (Slowly). Do you ever wonder what your female subjects might be thinking as you chip away…sculpting them in stone? DAEDALUS No! LYDIA Until you do, your creatures will just be cock teasers…fantasies for desperate, lonely men…nothing more. -

Jason and the Argonauts Pictures of …

Punctuating lists. There are different ways to write them, but some rules need to be followed. Imagine you are a sailor on the boat. What items will you take? Lists can be written in different ways. On the boat I took with me: • A first aid kit, • A sketchpad, • Some paints. Write some lists of your own. Show the On the boat I took with me: different ways you • a first aid kit, can punctuate • a sketchpad, them. • some paints. • On the boat I took with me: • A first aid kit in case of emergencies; • A sketchpad so I could record my adventures; • Some paints to create detailed pictures. Jason and the Argonauts Pictures of … • Hydra Golden Fleece • Centaur Argo • Clashing Rocks • How do you think these are involved in the story? Why? Discuss and then write down your answers. • 1. Who looked after Jason when his father was thrown in prison? • 2. What three subjects did Jason learn whilst he was living in the mountains? • 3. Why did Jason have to accept Pelias’ challenge? • 4. Find and copy a phrase that tells you what the goddess Athene did to make sure the Argo would be safe? • 5. Name three people who joined Jason on the Argo? 5 minutes Answers • 1. The Cenataurs • 2. hunting, sailing, history • 3. Because if he didn’t everyone would say he was a coward. • 4. Athene blessed the ship. • 5. Any three of: Heracles, Atalanta, Orpheus, Castor or Pollux. Use evidence from the text (p15) to explain your answers. • 1. Why do you think Pelias sent Jason to find the Golden Fleece? Explain. -

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr. Louis Markos Outline: Jason Jason was a foundling, who was a royal child who grew up as a peasant. Jason was son of Eason. Eason was king until Pelias threw him into exile, also sending Jason away. When he came of age he decided to go to fulfill his destiny. On his way to the palace he helped an old man cross a river. When Jason arrived he came with only one sandal, as the other had been ripped off in the river. Pelias had been warned, “Beware the man with one sandal.” Pelias challenges Jason to go and bring back the Golden Fleece. About a generation or so earlier there had been a cruel king who tried to gain favor with the gods by sacrificing a boy and a girl. o Before he could do it, the gods sent a rescue mission. They sent a golden ram with a golden fleece that could fly. The ram flew Phrixos and Helle away. o The ram came to Colchis, in the southeast corner of the Black Sea. Helle slipped and fell and drowned in the Hellespont, which means Helle’s bridge (between Europe and Asia). o Phrixos sacrificed the ram and gave the fleece as a gift to the people of Colchis, to King Aeetes. o The Golden Fleece gives King Aeetes power. Jason builds the Argo. The Argonauts are the sailors of the Argo. Jason and the Argonauts go on the journey to get the Golden Fleece. Many of the Argonauts are the fathers of the soldiers of the Trojan War. -

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell

STUDY GUIDE Photo of Mark L. Montgomery, Stephanie Andrea Barron, and Sandra Marquez by joe mazza/brave lux, inc Sponsored by Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides Translated by Nicholas Rudall Directed by Charles Newell SETTING The action takes place in east-central Greece at the port of Aulis, on the Euripus Strait. The time is approximately 1200 BCE. CHARACTERS Agamemnon father of Iphigenia, husband of Clytemnestra and King of Mycenae Menelaus brother of Agamemnon Clytemnestra mother of Iphigenia, wife of Agamemnon Iphigenia daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra Achilles son of Peleus Chorus women of Chalcis who came to Aulis to see the Greek army Old Man servant of Agamemnon, was given as part of Clytemnestra’s dowry Messenger ABOUT THE PLAY Iphigenia in Aulis is the last existing work of the playwright Euripides. Written between 408 and 406 BCE, the year of Euripides’ death, the play was first produced the following year in a trilogy with The Bacchaeand Alcmaeon in Corinth by his son, Euripides the Younger, and won the first place at the Athenian City Dionysia festival. Agamemnon Costume rendering by Jacqueline Firkins. 2 SYNOPSIS At the start of the play, Agamemnon reveals to the Old Man that his army and warships are stranded in Aulis due to a lack of sailing winds. The winds have died because Agamemnon is being punished by the goddess Artemis, whom he offended. The only way to remedy this situation is for Agamemnon to sacrifice his daughter, Iphigenia, to the goddess Artemis. Agamemnon then admits that he has sent for Iphigenia to be brought to Aulis but he has changed his mind. -

Page 147 of Microsoft Word

УДК 82'01''Медея'' THE SOURCES OF THE MYTH OF MEDEA IN THE POSITIVE LIGHT OF THE PRE-EURIPIDIAN INTERPRETATIONS AND THEIR EVOLUTION IN THE NEGATIVE SHADE Vazhynska Olena Ihorivna, Postgraduate student Taras Shevchenko University of Kiev The present article is dedicated to the analysis of the pre-Euripidian sources and literary premises of a classical version of the myth of Medea. The very first references and details of the character are being exam- ined in this research in order to give the readers a full comprehension of the construction of an image of a barbarian, murder, mother and lover which interlace in all its complicity of features. Key words: allusions of Medea in pre-Euripidian literature, sources of the myth, construction of the image of Medea. In a world literary tradition the source of the myth of Medea is considered to be the homonymous drama of Euripides, dated 431 BC. Due to the great influence and authority of the ancient poet, his drama became a source of a reference for a range of distinguished authors, such as Corneille, Grillparzer, Alvaro, Anouilh, Tomassini, Theodorakis, Mül- ler, etc.1. However, the aim of this research is to reveal the existence of the image of Medea long time before the version of Euripides, thus, we will examine the first mentions of the hypostasis in the early pre-Eurpidian literature that existed long time before the creation of the classical variant. According to the purpose of the research paper, we can determine the following objectives: 1) to identify the pre-Euripidian texts related to the myth of Medea; 2) to define the first allusions of Medea and Argonauts in the Antiquity; 3) to confront the early mentioning with the subsequent image of Medea; 4) to reveal the positive nature of the character in pre-Euripidian literature. -

THE ARGONAUTIKA He'd Gone on His Vain Quest with Peirithoos: That Couple Would Have Made Their Task's Fulfillment Far Easier for Them All

Book I Starting from you, Phoibos, the deeds ofthose old-time mortals I shall relute, who by way ofthe Black Sea's mouth and through the cobalt-dark rocks, at King Pelias 's commandment, in search of the Golden Fleece drove tight-thwarted Argo. For Pelias heard it voiced that in time thereafter a grim fate would await him, death at the prompting of the man he saw come, one-sandaled, from folk in the country: and not much later-in accordance with your word-Jason, fording on foot the Anauros's wintry waters, saved from the mud one sandal, but left the other stuck fast in the flooded estuary, pressed straight on to have his share in the sacred feast that Pelias was preparing for Poseidon his father, and the rest of the gods, though paying no heed to Pelasgian Hera. The moment Pelias saw him, he knew, and devised him a trial of most perilous seamanship, that in deep waters or away among foreign folk he might lose his homecoming. ,\row singers before 7ny time have recounted how the vessel was fashioned 4 Argos with the guidance of Athena. IW~cctIplan to do now is tell the name and farnib of each hero, describe their long voyage, all they accomplished in their wanderings: may the Muses inspire mnj sinpng! First in our record be Orpheus, whom famous Kalliope, after bedding Thracian Oikgros, bore, they tell us, 44 THE XRGONAUTIKA hard by Pimpleia's high rocky lookout: Orpheus, who's said to have charmed unshiftable upland boulders and the flow of rivers with the sound of his music. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

'Heroes of the Dance Floor': the Missing Exemplary Male Dancer In

‘Heroes of the Dance Floor’: The Missing Exemplary Male Dancer in Ancient Sources ‘Why, after the reign of the dancing Sun King, was dance no longer an appropriate occupation for men?’ This is the question with which Ann Daly opened an influential intervention in the feminist debate on dance. She argued, with the support of revealing quotations from the Romantic dance critic Theophile Gautier, that in the Romantic era dance became 'less a moral paradigm and more a spectacle'; the ballerina became a reified object for scrutiny, she says, by the male gaze: Because the connotative passivity of such overt display was anathema to the virile, strong, action-oriented control of the masculine ideology, dance came to be identified as "effeminate"… She argues that men’s effective prohibition from engaging in this self-display during high Romanticism indicates, furthermore, 'an attempt to maintain the male's virile image-his dominance-untainted by the "feminine." ' 1 In a nutshell, ever since Louis XIV, dance has been seen as fundamentally effeminate; since we live under patriarchy, in which the female body is the principle bearer for society of erotic signification, the perceived effeminacy of dance inevitably results in it becoming conceptually sexualised and vulnerable to charges of moral depravity and aesthetic decline. These connotations add up to what we understand by ‘decadence’ in the widest sense of that term, incorporating also a sense of a lapsarian fall from Edenic innocence.2 To dance was and still is to run the risk of relinquishing autonomous control over the 1 meaning created by one's own body, and thus to relinquish all that is signified by masculinity in culture. -

Female Characters, Female Sympathetic Choruses, and the “Suppression” of Antiphonal Lament at the Openings of Euripides’ Phaethon, Andromeda, and Hypsipyle*

FRAMMENTI SULLA SCENA (ONLINE) Studi sul dramma antico frammentario Università deGli Studi di Torino Centro Studi sul Teatro Classico http://www.ojs.unito.it/index.php/fss www.teatroclassico.unito.it ISSN 2612-3908 1 • 2020 FEMALE CHARACTERS, FEMALE SYMPATHETIC CHORUSES, AND THE “SUPPRESSION” OF ANTIPHONAL LAMENT AT THE OPENINGS OF EURIPIDES’ PHAETHON, ANDROMEDA, AND HYPSIPYLE* VASILIKI KOUSOULINI NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS [email protected] Female choruses abound in Euripides’ plays.1 While there are many in his extant plays, we also encounter choruses of women in his fragmentary ones.2 Little attention has been paid to the existence of sympathetic female choruses in Euripides’ fragmentary dramas and their in- teraction with female characters. A sympathetic female chorus seems to appear in conjunction with a female character in many Euripidean fragmentary plays. The chorus of the Alexander in * This research is co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Social Fund- ESF) through the Opera- tional ProGramme «Human Resources Development, Education and LifelonG LearninG» in the context of the pro- ject “Reinforcement of Postdoctoral Researchers - 2nd Cycle” (MIS-5033021), implemented by the State Scholar- ships Foundation (ΙΚΥ). 1 There is a female chorus in Euripides’ Medea, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba, Suppliant Women, Ion, Electra, Trojan Women, Iphigenia among the Taurians, Helen, Phoenician Women, Orestes, Iphigenia in Aulis, and Bacchae. Mastronarde observed that there are 15 male choruses, 62 female choruses, and 105 choruses with undetermined gender in Euripides’ corpus. Cf. MASTRONARDE 2010, 103. AccordinG to Calame, the 82% of Euripides’ traGic choruses con- sists of women. Cf. CALAME 2020, 776. -

Wulf: Libretto

WULF: LIBRETTO compiled by Vic Hoyland [Since most of this score uses modern English, it will be acceptable to perform this work using a translation in the country of performance, as well as using segments in the original French, Icelandic, Anglo‐Saxon, Latin, ancient Greek and Scottish Gaelic. Please contact UYMP to discuss any translation of the English text.] Iliad, chapter 18 (of 24): Patroclus, Achilles’ companion, is killed in battle. Achilles’ emotional reaction is extreme. His screams are heard by his mother, Thetis, from the depths of the sea. She calls on her nymphs (Nereids) to come to her son’s aid. “With these the bright cave was filled, and the nymphs all alike, beat their breasts, and Thetis led the lament.” The names of ancient Greek sea nymphs are recalled throughout the work. Part I – WULF 1. Glauke te Thaleia te Kymodoke te Nesaie Speio te Thoe Halia te Kymothoe te kai Actaee kai Limnoreia Kai Melite kai Iera kai Amphithoe kai Agave Doto te Proto te Pherusa Dynamene te Dexamene te Amphinome kai Kallineira Doris kai Panope kai te Galateia Nemertes te kai Apseudes kai Kallinassa Te Klymene Ianeira te kai Ianassa Maera kai Oreithyia te Amatheia.1 5. Protesilaus, Echepolus, Elephenor, Simoisius, Leukos, Democoon, Diores, Pirous, Phegeus, Idaeus, Odios, Phaestus, Scamandrius, Pherecles, Pedaeus, Hypsenor, Astynoos, Hyperion, Abas, Polyidos, Xanthus, Thoon, Echemmnon, Chromius, Pandarus, Deicoon.2 6. Sigmund took his weapons, but Skarphedinn waited the while. Skyolld turned against Grim and Helgʹ, and they fought violently. Sigmund had a helmet on his head and a shield at his side and was girt with a sword, his spear was in his hand; he turns against Skarphedinn, and thrusts at him with his spear, and the thrust struck the shield. -

ABSTRACT a Director's Approach to Euripides' Hecuba Christopher F. Peck, M.F.A. Mentor: Deanna Toten Beard, Ph.D. This Thesi

ABSTRACT A Director’s Approach to Euripides’ Hecuba Christopher F. Peck, M.F.A. Mentor: DeAnna Toten Beard, Ph.D. This thesis explores a production of Euripides’ Hecuba as it was directed by Christopher Peck. Chapter One articulates a unique Euripidean dramatic structure to demonstrate the contemporary viability of Euripides’ play. Chapter Two utilizes this dramatic structure as the basis for an aggressive analysis of themes inherent in the production. Chapter Three is devoted to the conceptualization of this particular production and the relationship between the director and the designers in pursuit of this concept. Chapter Four catalogs the rehearsal process and how the director and actors worked together to realize the dramatic needs of the production. Finally Chapter Five is a postmortem of the production emphasizing the strengths and weaknesses of the final product of Baylor University’s Hecuba. A Director's Approach to Euripides' Hecuba by Christopher F. Peck, B.F.A A Thesis Approved by the Department of Theatre Arts Stan C. Denman, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee DeAnna Toten Beard, Ph.D., Chairperson David J. Jortner, Ph.D. Marion D. Castleberry, Ph.D. Steven C. Pounders, M.F.A. Christopher J. Hansen, M.F.A. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2013 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. Copyright © 2013 by Christopher F. Peck