Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montauban 1780 - Paris 1867

Jean-Auguste-Dominique INGRES (Montauban 1780 - Paris 1867) Portrait of Gaspard Bonnet Pencil. Laid down. Signed and dated Ingres Rome / 1812 at the lower right. 222 x 161 mm. (8 3/4 x 6 3/8 in.) Around 460 portrait drawings by Ingres are known today, most of which date from before 1824, when he left Italy and returned to Paris. His Roman portrait drawings can be divided into two distinct groups; commissioned, highly finished works for sale, and more casual studies of colleagues and fellow artists, which were usually presented as a gift to the sitter. He had a remarkable ability of vividly capturing, with a few strokes of a sharpened graphite pencil applied to smooth white or cream paper, the character and personality of a sitter. (Indeed, it has been noted that it is often possible to tell which of his portrait subjects the artist found particularly sympathetic or appealing.) For his drawn portraits, Ingres made use of specially prepared tablets made up of several sheets of paper wrapped around a cardboard centre, over which was stretched a sheet of fine white English paper. The smooth white paper on which he drew was therefore cushioned by the layers beneath, and, made taut by being stretched over the cardboard tablet, provided a resilient surface for the artist’s finely-executed pencil work. A splendid example of Ingres’s informal portraiture, the present sheet was given by the artist to the sitter. It remained completely unknown until its appearance in the 1913 exhibition David et ses élèves in Paris, where it was lent from the collection of the diplomat Comte Alfred-Louis Lebeuf de Montgermont (1841-1918) and identified as a portrait of ‘M. -

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850 Gallery 15

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 - 5 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. At this point in Domenichino’s career he wanted more commissions for narrative scenes and knew he needed to demonstrate his skill in depicting human action. -

LE SALON ET SES ARTISTES Et Sculpture Étaient Des Corps De Métiers Ordinaires

TABLE DES MATIÈRES Avant-propos d’Arnaud d’Hauterives 5 Chapitre I : Du XVIIe siècle à la Révolution Française 9 L’origine du Salon 9 La peinture d’histoire 17 La scène de genre 29 Le portrait 35 Le genre paysager 38 La nature morte et la peinture animalière 41 Les grands sculpteurs 46 Les maîtres graveurs et tapissiers 50 Les femmes artistes 54 Chapitre II : De la Révolution à la IIIe République 59 La période révolutionnaire (1789-1804) 59 Les Salons de l’Empire (1804-1814) 72 Restauration et Monarchie de Juillet (1814-1848) 87 Seconde République et Seconde Empire (1848-1870) 109 La jeune Troisième République (1871-1880) 122 Chapitre III : Au XXe siècle 133 Naissance de la Société des Artistes français (1881-1914) 133 Peinture et sculpture de la Belle Époque à la Grande Guerre 140 Dans la tourmente de l’histoire 147 L’ère contemporaine 156 Indications bibliographiques 167 Index des noms 171 Crédits photographiques 176 AVANT-PROPOS Depuis sa création, le Salon a toujours été associé à l’Académie des Beaux-Arts de l’Institut de France, celle-ci décernant les distinctions, attribuant les Prix, dont le célébrissime Prix de Rome, à charge pour le Salon de faire connaître les artistes honorés par cette der- nière. Comme toute institution, le Salon a connu ses heures de gloire de même que ses vicissitudes pour ne pas dire « ses creux de vague ». À l’heure présente, il demeure le doyen des salons. Souvent jalousé, envié, dénigré, convoité, le Salon demeure une force vivante, chaleureuse, répondant aux attentes des artistes. -

Rome Vaut Bien Un Prix. Une Élite Artistique Au Service De L'état : Les

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 8 Article 8 Issue 2 The Challenge of Caliban 2019 Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger Artl@s, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Verger, Annie. "Rome vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968." Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 2 (2019): Article 8. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. Artl@s At Work Paris vaut bien un prix. Une élite artistique au service de l’État : Les pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome de 1666 à 1968 Annie Verger* Résumé Le Dictionnaire biographique des pensionnaires de l’Académie de France à Rome a essentiellement pour objet le recensement du groupe des praticiens envoyés en Italie par l’État, depuis Louis XIV en 1666 jusqu’à la suppression du concours du Prix de Rome en 1968. -

Herminie a Performer's Guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix De Rome Cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata Rosella Lucille Ewing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Ewing, Rosella Lucille, "Herminie a performer's guide to Hector Berlioz's Prix de Rome cantata" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2043. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2043 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HERMINIE A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HECTOR BERLIOZ’S PRIX DE ROME CANTATA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music and Dramatic Arts by Rosella Ewing B.A. The University of the South, 1997 M.M. Westminster Choir College of Rider University, 1999 December 2009 DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this document and my Lecture-Recital to my parents, Ward and Jenny. Without their unfailing love, support, and nagging, this degree and my career would never have been possible. I also wish to dedicate this document to my beloved teacher, Patricia O’Neill. You are my mentor, my guide, my Yoda; you are the voice in my head helping me be a better teacher and singer. -

Biochronologie Ingres

Édition définitive Biochronologie Ingres Éric Bertin avec l’assistance de Joanna Walkowska-Boiteux Avertissement L’explication des conventions d’écriture adoptées est fournie en page 399 de l’ouvrage. Sommaire Chapitre 1 Chapitre 2 Chapitre 3 Chapitre 4 Chapitre 5 Chapitre 6 Chapitre 7 Chapitre 8 Notes du chapitre 1 Notes du chapitre 2 Notes du chapitre 3 Notes du chapitre 4 Notes du chapitre 5 Notes du chapitre 6 Notes du chapitre 7 Notes du chapitre 8 Annexe A Annexe B Annexe C Annexe D Chapitre 1 : Montauban–Toulouse–Paris, 1780–1806 -1780 Le 29 août, naissance à Montauban — chef-lieu de la généralité de Montauban, puis, à partir de 1808, du dépar- tement de Tarn-et-Garonne — de Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, fils de Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres (1755– 1814), peintre et sculpteur, et d’Anne Moulet (1758–1817), son épouse. Le futur peintre n’eut pas moins de sept frères et sœurs, tous nés à Montauban comme lui, sauf un. Naquirent à Montauban : Anne (1782–1784), Jacques (1785–1786), Jeanne (1787–1863) — qui se fera appeler Augustine et qui épousera Clément Dechy en 1824 —, Jeanne-Anne-Marie (1790–1870) — qui survivra à son frère aîné — et deux jumeaux : Pierre-Victor (1799–1803) et Thomas-Alexis (1799–1821). Naquit « aux environs de Montauban » : Joseph — dont il sera question ci-après (1835) —. 80 Le lendemain, Ingres est ondoyé, « dans la maison du père de l’enfant » ; le 14 septembre, il est baptisé. = 80 Ingres : son prénom courant, l’orthographe de son nom et son année de naissance Le prénom utilisé dans la plupart des lettres d’Ingres où le nom est précédé du prénom est Jean, ou, plus généralement, J. -

Ex. #8 Prix De Rome News Report

Art Radar Contemporary art trends and news from Asia and beyond Skip to primary content Skip to secondary content HOME CITY MEET UPS OPPORTUNITIES OUR TEAM ASIAN ART EVENTS LEARNING MEMBERS READERSHIP ABOUT CONTACT SUBSCRIBE About Art Radar Art Radar is the only editorially independent online news source writing about contemporary art across Asia. Art Radar conducts original research and scans global news sources to bring you the taste-changing, news-making and up-and-coming in Asian contemporary art. NEW! Art Career Accelerator Group We have just set up a shiny new Facebook group. To ignite your art career join today. Join Art Career Accelerator Facebook Group here Looking for an Internship in the art world? Art Radar compiles some of the best opportunities for you. If you are interested in a comprehensive list of internships in the field of art, click here to sign up for our mailing list! Get published in 2018 The Art Radar Diploma in Art Journalism and Writing is a unique course that guarantees publication. You'll receive one-on-one personal feedback and build a portfolio of published writing to show future employers, editors and grant distributors. Click here to find out how to apply and what it costs. Free opportunities listings! We're offering free opportunity listings to all of our readers. Your listing will appear here. If you would like to advertise your opportunity to over 20,000 visitors a month, fill out our Internships or Opportunities submission form. Post navigation ← Artist Job Fair: a project by Wok The Rock with Videshiiya & friends “Crash Dig Dwell”: intersecting art and architecture with Indian artists Asim Waqif and Yamini Nayar – in conversation → Lebanese artist Rana Hamadeh wins Prix de Rome Visual Arts 2017 Posted on 09/01/2018 ! Follow Like27 in Share Tweet 5 Votes Visual and performance artist Rana Hamadeh is unanimously selected as the recipient of the Prix de Rome Visual Arts 2017. -

James Pradier (1790–1852) Et La Sculpture Française De La Génération Romantique: Catalogue Raisonné by Claude Lapaire

Marc Fehlmann book review of James Pradier (1790–1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique: Catalogue Raisonné by Claude Lapaire Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2010) Citation: Marc Fehlmann, book review of “James Pradier (1790–1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique: Catalogue Raisonné by Claude Lapaire,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2010), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn10/james- pradier-1790n1852-et-la-sculpture-francaise-de-la-generation-romantique. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Fehlmann: James Pradier (1790–1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2010) James Pradier (1790-1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique. Catalogue raisonné. Claude Lapaire Zürich/Lausanne: Swiss Institute for Art Research; Milan: 5 Continents Edition, 2010. 512 pp; 838 duotone illustrations Cost: CHF 140. (ca. $120.) ISBN: 978-88-7439-531-6 Charles Baudelaire blamed him for the "pitiable state of sculpture today" and alleged that "his talent is cold and academic,"[1] while Gustave Flaubert felt that he was "a true Greek, the most antique of all the moderns; a man who is distracted by nothing, neither by politics, nor socialism, Fourier or the Jesuits […], and who, like a true workman, sleeves rolled up, is there to do his task morning till night with the will to do well and the love of his art."[2] Both are discussing the same man, one of the leading artists of late Romanticism and the "king of the sculptors" during the July Monarchy: Jean-Jacques Pradier (23 May 1790 – 4 June 1852), better known as James.[3] Born in Geneva to a hotelkeeper, Pradier left for Paris at the tender age of 17 to follow his elder brother, Charles-Simon Pradier, the engraver. -

Jacques-Louis David: in Quest of a Hero

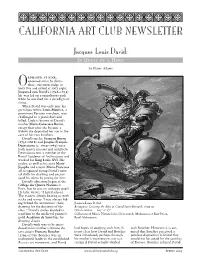

YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY CALIFORNIA ART CLUB NEWSLETTER Jacques-Louis David: In Quest of a Hero by Elaine Adams rphaned at nine, esteemed artist by thirty- Othree, execution judge at forty-five and exiled at sixty-eight; Jacques-Louis David’s (1748–1825) life was led on a tumultuous path while he searched for a paradigm of virtue. When David was only nine his garrulous father, Louis-Maurice, a prominent Parisian merchant, was challenged to a pistol duel and killed. Little is known of David’s mother Marie-Geneviève Buron, except that after she became a widow she deposited her son in the care of her two brothers. David’s uncles, François Buron (1731–1818) and Jacques-François Desmaisons (c. 1720–1789) were both master masons and architects; Desmaisons was a member of the Royal Academy of Architecture and worked for King Louis XVI. His uncles, as well as his aunt Marie- Josephe and cousin Marie-Francoise all recognized young David’s natu- ral skills for drawing and encour- aged his talent by posing for him. David’s education began at the Collège des Quatre Nations in Paris, but he was an unhappy pupil. He later wrote, “I hated school. The masters always beating us with sticks and worse. I was always hid- ing behind the instructors’ chair, Jacques-Louis David drawing for the duration of the Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at Grand-Saint-Bernard, 1800-01 class.” David’s uncles decided to Oil on canvas 103Љ ϫ 87Љ send him to the medieval painter’s Collection of Musée National des Châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau, guild Académie de Saint-Luc for Reuil-Malmaison drawing classes. -

Architectural Education at Cornell: 1928-1950

ARCHITECTURAL EDUCATION AT CORNELL: 1928-1950 BETWEEN MODERNISM AND BEAUX-ARTS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christian Ricardo Nielsen-Palacios August August 1991 and 2018 May 2018 © 2018 Christian Ricardo Nielsen-Palacios ABSTRACT Cornell University’s School of Architecture, the second oldest in the United States, enjoyed for many years a reputation as a quintessential “French” school, based on the teaching methods of the École de Beaux Arts in Paris. Its students and alumni did very well in design competitions, and went on to successful careers all over the country. When the author attended architecture school in Caracas, the majority of the faculty were Cornell alumni from the 50s. Their focus was on modernism, and when they reminisced about Cornell they talked mostly about what they learned studying Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Gropius, among others. For this thesis the author reviewed documents in the university’s archives and corresponded with alumni of the era, in order to look at the transitional period between those two phases in the life of the Cornell school. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Christian Nielsen-Palacios was born in Caracas, Venezuela, of a Danish father (Nielsen) and a Venezuelan mother (Palacios). He attended a Jesuit high school, graduating near the top of his class. He then came to the United States to prepare for college by repeating the final year of high school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey. Being homesick, he returned to Venezuela and enrolled in what was one of the best and more progressive universities in the country, the “experimental” Universidad Simón Bolívar, founded in the late 60s. -

Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’S Faust Et Hélène

La Victoire du péril rose: Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’s Faust et Hélène Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Music Eric Chafe, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Musicology by Julie VanGyzen May, 2014 Copyright by Julie VanGyzen © 2014 Abstract La Victoire du Péril Rose: Contextualizing Sociological Narratives and Wagnerian Aesthetics in Lili Boulanger’s Faust et Hélène A thesis presented to the Department of Music Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Julie VanGyzen On July 5th, 1913, the instructors of the Académie des Beau-Arts of France, the institutes responsible for the production of French artists, announced an unexpected and unprecedented victor of the distinguished Prix de Rome competition in composition. Nineteen-year-old Lili Boulanger was the new sound of French music. Never before had a woman composer won first place in the century old Prix de Rome due to the conservative political views shared by the Académie and the misogyny of the competition’s jury. This momentous event has been given much attention in the research of Boulanger’s Prix de Rome success through sociological perspective on France in 1913; a bourgeoning feminist atmosphere in the increasingly liberal government of France influenced the jury’s decision to award Boulanger the Premier Grand Prix. Contemporary English musicological scholarship has favored this socio-historical narrative over analysis the aesthetic character of her winning cantata, Faust et Hélène, thereby neglecting another significant facet to Boulanger’s win; her overt incorporation of motifs from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. -

Rory Pilgrim Wins Prix De Rome Visual Arts 2019

Press Release Amsterdam, 31 October 2019 LTR: Dutch Minister of Education, Culture and Science Ingrid van Engelshoven, winner Prix de Rome 2019 Rory Pilgrim, Queen Máxima, director Mondriaan Fund Eelco van der Lingen. Photo: Shinji Otani Rory Pilgrim wins Prix de Rome Visual Arts 2019 Artist Rory Pilgrim (Bristol, 1988) received the Prix de Rome Visual Arts 2019 from the Dutch Minister of Education, Culture and Science, Ingrid van Engelshoven, in the presence of Queen Máxima. Pilgrim received this award for his new film The Undercurrent (2019-ongoing). The award comes with a 40,000 Euros cash prize and a work period at the American Academy in Rome. The Prix de Rome is awarded once every two years to a talented visual artist in the Netherlands. Rory Pilgrim made the fifty-minute film The Undercurrent in which he transports the visitors to the world of a group of young people in the American city of Boise (Idaho). The film features beautiful cinematography, wonderful music, and is meticulously edited. Furthermore, the artist raises a number of topical issues in the film. Initially, climate change appears to be its most important theme, but gradually it becomes clear that the young people have other problems too. Central to this film is a house that appears to function as a sanctuary for the main characters. The concept of the sanctuary is also used for the protection of nature. In this way, the film is hinting at a subtle connection between the earth that needs attention and protection, and the young people who need a home for intimacy, security and their future.