Multi0page.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Organizational Chart

I. Organizational Chart SBP BANKING SERVICES CORPORATION Board of Directors Managing Director Aftab Mustafa Khan MD Secretariat Head Office Field Offices Personnel Management Currency Management Department Karachi Office Lahore Office Department Javaid Iqbal Taslim Kazi Dr.Muhammad Saleem Amjad Manzoor Chief Manager Chief Manager Director Director Islamabad Office Peshawar Office Foreign Exchange Operations Development Finance Support Tariq Riaz Muhammad Tanwirul Islam Department Department Chief Manager Chief Manager Syed Shahzad Safdar Zaidi Muhammad Mazharul Haq Director Director Rawalpindi Office Quetta Office Asad Shah Ali Hussain Chief Manager Chief Manager * Training & Development Department Accounts Department Amjad Manzoor Muhammad Habib Khan Director* Director Hyderabad Office Faisalabad Office Ali Hussain Sajjad Ali Shah Chief Manager Chief Manager General Services Department Internal Audit Department Zafar Iqbal Maraj Mahmood Director Head Multan Office North Nazimabad Office Javaid Iqbal Marath Ansar Iftikhar Butt Chief Manager Chief Manager Quality Assurance Department Engineering Department Feroza Nabeel Qureshi Fazli Hameed Director Head Muzaffarabad Office Sukkur Office Muhammad Tahir Malik Muhammad Ashraf Khokhar Chief Manager (A) Chief Manager Foreign Exchange Adjudication Department Internal Bank Security Muhammed Saleem Rehmani Department Brig.(R) M. Pervez Akbar Bahawalpur Office Gujranwala Office Director Khadim Hussain Aamir Nazir Bhatti Director Chief Manager (A) Chief Manager (A) * Additional Charge Sialkot Office D.I. Khan Office ( A) Acting Basis Azhar Iqbal Muhammad Humayun Khan Chief Manager Chief Manager Annual Performance Review of SBP BSC FY12 II. Board of Directors S # Name Status 1 Mr. Yaseen Anwar Governor SBP/ Chairman of SBP BSC Board 2 Mr. Abdul Wajid Rana Member/ Principal Officer, Finance Division, GoP 3 Mr. Mirza Qamar Beg Member 4 Mr. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Pdf | 564.01 Kb

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Weekly Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | 13 October 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • Weekly average retail prices update as of 8th of October 2020 indicates overall the prices of staple cereals and non-cereals foods experienced negligible to slight fluctuations, except for eggs which experienced a significant increase, when compared to the previous week’s prices; • Cereals: (wheat, wheat flour, rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati). Overall, the average retail prices for wheat and wheat flour slightly increased along with negligible increases in the prices of rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati from the previous week; • Non-cereals: overall, compared to the previous week, the average retail prices of essential non-cereals registered a significant increase for eggs along with a slight increase for live chicken and negligible increases for sugar, cooking oil, pulses gram and Masoor. Whereas, negligible decreases were noted in the prices of pulses Mash and Moong while the price of vegetable ghee remained unchanged from the previous week; • The average ToT slightly decreased by 4% from the previous week. Market Monitor | Pakistan | 13 October 2020 Page 2 To monitor the impact of COVID-19 on market prices, the average retail prices1 of cereals and non-cereals essential food commodities across the country’s main markets2 in or near COVID-19 hotspots cities (Swat, Peshawar, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, Sialkot, Gujranwala, Faisalabad, Gujrat, Lahore, Multan, Ghotki, Sukkur, Hyderabad, Karachi and Quetta)3 -

TCS Offices List.Xlsx

S No Cities TCS Offices Address Contact 1 Hyderabad TCS Office Agriculture Shop # 12 Agricultural Complex Hyderabad 0316-9992350 2 Hyderabad TCS Office Rabia Square SHOP NO:7 RABIA SQUARE HYDER CHOCK HYDERABAD SINDH PAKISTAN 0316-9992351 3 Hyderabad TCS Office Al Noor Citizen Colony SHOP NO: 02 AL NOOR HEIGHTS JAMSHORO ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992352 4 Hyderabad TCS Office Qasimabad Opposite Larkana Bakkery RIAZ LUXURIES NEAR CALTEX PETROL PUMP MAIN QASIMABAD ROAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992353 5 Hyderabad TCS Office Market Tower Near Liberty Plaza SHOP NO: 26 JACOB ROAD TILAK INCLINE HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992354 6 Hyderabad TCS Office Latifabad No 07 SHOP NO" 01 BISMILLAH MANZIL UNIT NO" 07 LATIFABAD HYDERABAD SINDH 0316-9992355 7 Hyderabad TCS Office Auto Bhan Opposite Woman Police Station Autobhan Road near women police station hyderabad 0316-9992356 8 Hyderabad TCS Office SITE Area Area Office Hyderabad SITE Autobhan road near toyota motors site area hyderabad 0316-9992357 9 Hyderabad TCS Office Fatima Height Saddar Shop No.12 Fatima Heights Saddar Hyderabad 0316-9992359 10 Hyderabad TCS Office Sanghar SHOP NO: 02 BAIT UL FAZAL BUILDING M A JINNAH ROAD SANGHAR 0316-9992370 11 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando allah yar SHOP NO: 02 MAIN BUS STOP NEAR NATIONA BANK TDA 0316-9992372 12 Hyderabad TCS Office Nawabshah Near PTCL SUMERA PALACE HOSPITAL ROAD NAAWABSHAH 0316-9992373 13 Hyderabad TCS Office Tando Muhammad Khan AL FATEH CHOCK ADJUCENT HABIB BANK STATION ROAD TANDO MOHD KHAN 0316-9992374 14 Hyderabad TCS Office Umer Kot JAKHRA MARKET -

Invitation for Bids

INVITATION FOR BIDS 1. National Highway Authority (NHA) Re-invites sealed bids from eligible construction firms registered with income tax department having valid PEC registration & specialization for the following works Sr PEC Category & Contract# Work Description / Route # Specialization Construction of 08 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 370- C-4 with Specialization 01 TP-2018-19-SN-01 371(N-5) Kandyaro in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 08 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 534- C-4 with Specialization 02 TP-2018-19-SN-02 535(N-5) Ghotki in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 483- C-5 with Specialization 03 TP-2018-19-SN-03 484(N-55) Kashmore in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 09- C-4 with Specialization 04 TP-2018-19-SN-04 10(LKBP) Larkana in CE-01 & CE-10 Construction of 06 Lanes Toll Plaza KM: 33- C-4 with Specialization 05 TP-2018-19-SN-05 34(M-8) Ratodero in CE-01 & CE-10 2. Complete set of bidding documents (for above mentioned Works), containing detailed terms and conditions, method of procurement (Single Stage – Two Envelope procedure) for submission of bids, bid security, bid validity, opening of bid, evaluation criteria, clarification/rejection of bids, performance guarantee etc. are available on NHA website for downloading free of cost. Bidders are also advised to follow the NHA website for updates of bidding schedule and addendum(s), if any 3. The bids prepared in accordance with the instructions contained in the bidding documents must reach at the address mentioned below on or before 16th July, 2021 until 1100 Hours. -

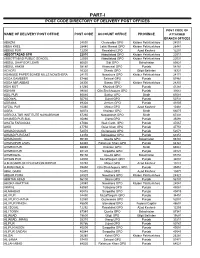

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

National Freight and Logistics Policy

NATIONAL FREIGHT AND LOGISTICS POLICY Ministry of Communications Government of Pakistan Final, 28 April 2020 National Freight and Logistics Policy Government of Pakistan Table of Content 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................4 2. State of Pakistan’s Freight and Logistics Sector ...................................................................................6 3. Justification for the NFLP .........................................................................................................................9 3.1. Rationale .............................................................................................................................................9 3.2. Potential Benefits ............................................................................................................................. 11 4. Vision, Principles and Objectives ......................................................................................................... 12 4.1. Vision Statement .............................................................................................................................. 12 4.2. Objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 13 4.3. Principles ......................................................................................................................................... -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

PESA-DP-Sukkur-Sindh.Pdf

Landsowne Bridge, Sukkur “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Sukkur September 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader development programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a K I S T a N

IUB Scores 100% in HEC Online Classes Dashboard The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, P a k i s t a n Vol. 21 October–December, 2020 Khawaja Ghulam Farid (RA) Seminar and Mehfil-e-Kaafi | 17 Federal Minister for National Food Security Additional IG Police South Punjab Commissioner Bahawalpur Inaugurates Visits IUB Agriculture Farm | 04 Visits IUB | 04 4 New Buses | 09 MD Pakistan Bait ul Mal Visits IUB | 03 Inaugural Ceremony of the Project Punjab Information Technology Board Cut-Flower and Vegetable Production Praises IUB E-Rozgar Center | 07 Research and Training Cell | 13 Honourable Governor Advises IUB to be Student-Centric and Employee-Friendly Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, briefed the Senate meeting of the University. particular, the Governor advised Vice Chancellor, the Islamia Honourable Chancellor about the The Governor appreciated the to University to be more student- University of Bahawalpur made a progress of the Islamia University performance of Islamia University centric and employee-friendly as courtesy call on Governor Punjab of Bahawalpur. Other matters of Bahawalpur and assured of his these ingredients were necessary and Chancellor of the University, discussed included the scheduling wholehearted support to Islamia for world-class universities. Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar. of upcoming Convocation and University of Bahawalpur. In Governor Punjab Chaudhary Muhammad Sarwar exchanging views with Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor National Convention on Peaceful University Campuses Engr. Prof. Dr. Athar Mahboob, Vice Chancellor, the Islamia University of Bahawalpur attended the Vice Chancellor’s Convention on peaceful Universities held in joint collaboration of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan and Inter University Consortium for Promotion of Social Sciences. -

Sukkur Barrage Rehabilitation and Modernization Public Disclosure Authorized

Government of Sindh, Pakistan Public Disclosure Authorized Sindh Barrages Improvement Project - Sukkur Barrage Rehabilitation and Modernization Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sindh Irrigation Department Public Disclosure Authorized December 2017 Contents List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................. iii 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Background .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Sindh Barrages Improvement Project (SBIP)........................................................ 2 1.3. The Environmental and Social Assessment.......................................................... 3 2. Policy, Legal and Administrative Framework ........................................................... 5 2.1. Applicable Legislation and Policies in Sindh, Pakistan ......................................... 5 2.2. Environmental Procedures ................................................................................... 6 2.3. World Bank Safeguard Policies ............................................................................ 6 3. Project Description ................................................................................................... 10 3.1. Description of Sukkur Barrage ........................................................................... -

Spatio-Temporal Changes in Economic Development: a Case Study of Sindh Province

Karachi University Journal of Science, 2012, 40, 25-30 25 Spatio-temporal Changes in Economic Development: A case study of Sindh Province Razzaq Ahmed1 and Khalida Mahmood2,* 1Department of Geography, Federal Urdu University of Arts Sciences and Technology, Karachi and 2Department of Geography, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan Abstract: This study has been conducted at a time when Pakistan is passing through an important phase of economic development and reconstruction. Devolution has become an important aspect of the planning and decision making process. Decentralization is being emphasized by both public and private sectors of development. In such a situation, present study focuses on the evaluation of the past and present patterns of the levels of development in various districts of the province of Sindh. This research will certainly contribute to an understanding of the development patterns in the province. Key Words: composite index, level of development, ranking, socio-economic inequality, Z-score. INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK Sindh has experienced considerable urbanization since To measure the level of development of the districts of independence in 1947, which has resulted in the explosive Sindh, twelve variables have been employed on thirteen 1 growth of urban centers like Karachi, Hyderabad and districts of 1981 and sixteen districts of 1998 . These Sukkur. The growth of Karachi in particular has been variables are non-agricultural labor force, employment in phenomenal. Its exceptional growth as compared to the rest manufacturing, immigration, own farm, cultivated area, of Sindh, which is basically rural in nature, brings out unique population potential, manufacturing value added (rupees per patterns of socio-economic inequality.