English Version of This Report Is the Only Official Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KAS MP SOE Redebeitrag AM En

REPORT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung MEDIA MONITORING LABORATORY February 2015 Media under their own momentum: www.fmd.bg The deficient will to change www.kas.de Foundation Media Democracy (FMD) and KAS. In summary, the main findings, by the Media Program South East Europe of areas of monitoring, include: the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) present the joint annual report on the MEDIA DISCOURSE state of the Bulgarian media environment in 2014. The study summarises the trends Among the most striking images in the coverage of socio-political constructed by Bulgarian media in 2014 was developments in the country. During the the presentation of patriotism as the monitored period dynamic processes sanctuary of identity. Among the most unfolded – European Parliament elections watched television events during the year and early elections to the National turned to be the Klitschko-Pulev boxing Assembly took place, three governments match. The event inflamed social networks, changed in the country’s governance. morning shows, commentary journalism. It was presented not simply as boxing, but as The unstable political situation has also an occasion for national euphoria. Such affected the media environment, in which a discourse fitted into the more general trend number of important problems have failed of nourishing patriotic passions which to find a solution. During the year, self- through the stadium language, but also regulation was virtually blocked. A vast through the media language, are easily majority of the media continued operating mobilised into street and political forms of at a loss. For many of them the problem symbolic and physical violence against with the ownership clarification remained others (Roma, refugees, the sexually and unresolved. -

Election Reaction: the Status Quo Wins in Bulgaria

Election reaction: The status quo wins in Bulgaria blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2017/03/27/2017-bulgarian-election-results-borisov-wins/ 27/03/2017 Bulgaria held parliamentary elections on 26 March, with preliminary results indicating that GERB, led by Boyko Borisov, had emerged as the largest party. Dimitar Bechev analyses the results, writing that despite the Bulgarian Socialist Party building on their success in last year’s presidential election to run GERB close, the results showed the resilience of the status quo in the country. Boyko Borisov, Credit: European People’s Party (CC-BY-SA-2.0) After running neck and neck with the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) for months on end, Boyko Borisov won again. He is battered and bruised. He did not win big, but win he did. Preliminary results give his party, GERB, 32.6% of the vote in Bulgaria’s parliamentary elections. The Socialists finished a close second with about 26.8%. They are disappointed, no doubt, but theirs is no mean achievement. In the last elections in October 2014, the BSP trailed much further behind Borisov (32.7% vs. 15.4%). Given the similar turnout in both elections (around 48%), it is clear the party did manage to capitalise on the momentum generated by their triumph in the November 2016 presidential elections, which were won by former general Rumen Radev. But the BSP will not rise to the position of top dog in Bulgarian politics. Table: Preliminary results of the 2017 Bulgarian election 1/3 Note: Results based on the official count (89%) as of the morning of 27 March (rounded to first decimal place). -

A Game of Polls: Bulgaria's Presidential Election Threatens To

A game of polls: Bulgaria’s presidential election threatens to shake up the country’s party system blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2016/10/31/game-of-polls-bulgaria-presidential-election/ 31/10/2016 Bulgaria will hold presidential elections on 6 November, with a second round runoff scheduled for 13 November. Dimitar Bechev previews the contest, writing that the candidate supported by the country’s largest party, GERB, could face a tougher contest than originally anticipated. Presidential elections in Bulgaria are supposed to be a rather dull affair. Many expected the candidate handpicked by Prime Minister Boyko Borisov to make it comfortably to the second round (to be held on 13 November), piggybacking on their patron’s popularity as well as the ruling party GERB’s (Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria) formidable electoral machine. To Borisov’s chagrin, that now seems less and less likely. Polls suggest that the race between his choice, parliament speaker Tsetska Tsacheva, and General Rumen Radev, backed by the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), will be tight. Not quite the suspense of the U.S. presidential contest, but certainly not lacking in drama either. And, to boot, the opposition frontrunner might actually have a fair chance. He could well rally the votes cast for United Patriots, an ultra-nationalist coalition between erstwhile sworn enemies the Patriotic Front and Ataka, for ABV (Alternative for Bulgarian Renaissance), a splinter group from the BSP, and several other minor players. Borisov has only himself to blame for this state of affairs. He delayed his choice as much as possible, unveiling Tsacheva at the very last moment – well after other contenders had stepped into the fray. -

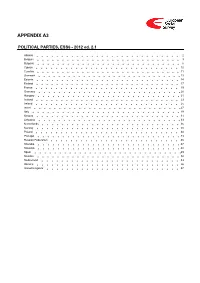

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

KAS MP SOE Redebeitrag AM En

REPORT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung and Foundation Media Democracy MEDIA MONITORING LABORATORY February 2016 THE DILEMMA OF THE MEDIA: JOURNALISM OR PROPAGANDA www.fmd.bg www.kas.de The Foundation Media Democracy (FMD) • An apathetic campaign for the local and the Media Program South East Europe elections which were held in October, where of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) media proved themselves to care more present their joint annual report on the about how they could profit from political state of the Bulgarian media environment advertising funds, allocated by the parties, in 2015. This study summarises the trends than about providing a stage for genuine in the coverage of socio-political debates among participants in the election developments in the country. race. The analyses in the report are conducted by • Examples of unprecedented attacks the research team of the Media Monitoring against the Council for Electronic Media Laboratory of FMD: Nikoleta Daskalova, (SEM) in the context of political strife. Media Gergana Kutseva, Eli Aleksandrova, Vladimir regulation was seriously threatened. At the Kisimdarov, Lilia Lateva, Marina Kirova, same time important debates and long- Ph.D., Silvia Petrova, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof. needed amendments to the media Todor Todorov, as well as by the guest legislation were not initiated. experts Assoc. Prof. Georgi Lozanov, Prof. Snezhana Popova and Prof. Totka Monova. In light of the above, the main conclusions The team was led by Assoc. Prof. Orlin by areas of monitoring can be summarised, Spasov. A part of the monitoring is based as follows: on quantitative and qualitative data, prepared by Market Links Agency for the NATIONAL TELEVISIONS, DAILY joint analysis of FMD and KAS. -

Review of European and National Election Results Update: September 2019

REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2019 A Public Opinion Monitoring Publication REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS UPDATE: SEPTEMBER 2019 Directorate-General for Communication Public Opinion Monitoring Unit May 2019 - PE 640.149 IMPRESSUM AUTHORS Philipp SCHULMEISTER, Head of Unit (Editor) Alice CHIESA, Marc FRIEDLI, Dimitra TSOULOU MALAKOUDI, Matthias BÜTTNER Special thanks to EP Liaison Offices and Members’ Administration Unit PRODUCTION Katarzyna ONISZK Manuscript completed in September 2019 Brussels, © European Union, 2019 Cover photo: © Andrey Kuzmin, Shutterstock.com ABOUT THE PUBLISHER This paper has been drawn up by the Public Opinion Monitoring Unit within the Directorate–General for Communication (DG COMM) of the European Parliament. To contact the Public Opinion Monitoring Unit please write to: [email protected] LINGUISTIC VERSION Original: EN DISCLAIMER This document is prepared for, and primarily addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official position of the Parliament. TABLE OF CONTENTS EDITORIAL 1 1. COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT 5 DISTRIBUTION OF SEATS OVERVIEW 1979 - 2019 6 COMPOSITION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LAST UPDATE (31/07/2019) 7 CONSTITUTIVE SESSION (02/07/2019) AND OUTGOING EP SINCE 1979 8 PROPORTION OF WOMEN AND MEN PROPORTION - LAST UPDATE 02/07/2019 28 PROPORTIONS IN POLITICAL GROUPS - LAST UPDATE 02/07/2019 29 PROPORTION OF WOMEN IN POLITICAL GROUPS - SINCE 1979 30 2. NUMBER OF NATIONAL PARTIES IN THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT CONSTITUTIVE SESSION 31 3. -

Where You Can Read the Full Country Chapter

Bulgaria During 2016, a series of important conversations were initiated in Bulgaria. These discussions did not lead to concrete policy changes during the year, but their subjects were of great relevance to LGBTI people. The Ministry of Justice working group on changes to the penal code included the voices of LGBTI NGOs. Its recommendation to include anti-LGBT bias as aggravating circumstances in criminal cases was particularly welcome when you consider the absence of any protection for LGBTI people against hate crime or hate speech on the Bulgarian statute books. A similar lack of protection for intersex people against human rights violations is also an issue; one of the most invasive of these is so-called ‘normalising’ surgery. The impact of these procedures and the need to stop the practice was discussed by intersex activists and medical students, with plans made for further interaction. The impact of the 2016 discussions between LGBTI activists and the authorities remains to be seen, as the work of the justice working group was put on hold until after elections, planned for 2017. The largest ever Sofia Pride is another milestone that activists hope can be replicated in the coming year. For more information on developments in 2016, visit www.rainbow-europe.org where you can read the full country chapter. ILGA-Europe Annual Review 2017 65 Legal and policy situation in Bulgaria as of 31 December 2016 Asylum Civil society space Equality & non-discrimination Legal gender recognition & bodily integrity Family Hate crime & hate speech In order to improve the legal and policy situation of LGBTI people, ILGA-Europe recommend: Developing a fair, transparent legal framework for legal gender recognition, based on a process of self-determination, free from abusive requirements (such as sterilisation, GID/medical diagnosis, or surgical/medical intervention). -

Factsheet: the Bulgarian National Assembly

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Bulgarian National Assembly 1. At a glance The Republic of Bulgaria is a parliamentary democracy. The Bulgarian Parliament (National Assembly or Narodno sabranie) is a unicameral body, which consists of 240 deputies elected directly by the voters from 32 constituencies to four-year terms, on the basis of the proportional system. Political parties must gather a minimum of 4% of the national vote in order to enter the Assembly. The National Assembly has three basic functions: legislative, control and constitutive. The major function of the National Assembly is to legislate by adopting, amending and rescinding laws. The control function of the National Assembly is to exercise oversight of the executive. The MPs contribute to effective work of the government and state administration by addressing questions and interpellations, and by requiring reports. The constitutive function of the National Assembly is to elect, on a motion from the Prime Minister, the members of the Council of Ministers, the President and members of the National Audit Office, the Governor of the Bulgarian National Bank and his/her Deputies, and the heads of other institutions established by a law. The current minority coalition government under Premier Minister Boyko Borisov (GERB/EPP), sworn in on 7 November 2014, is composed of the conservative GERB party (EPP) and the centre- right Reformist Bloc (RB/EPP), with the support of nationalist Patriotic Front coalition -

The Reality Behind the Rhetoric Surrounding the British

‘May Contain Nuts’? The reality behind the rhetoric surrounding the British Conservatives’ new group in the European Parliament Tim Bale, Seán Hanley, and Aleks Szczerbiak Forthcoming in Political Quarterly, January/March 2010 edition. Final version accepted for publication The British Conservative Party’s decision to leave the European Peoples’ Party-European Democrats (EPP-ED) group in the European Parliament (EP) and establish a new formation – the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) – has attracted a lot of criticism. Leading the charge have been the Labour government and left-liberal newspapers like the Guardian and the Observer, but there has been some ‘friendly fire’ as well. Former Conservative ministers - so-called ‘Tory grandees’ - and some of the party’s former MEPs have joined Foreign Office veterans in making their feelings known, as have media titles which are by no means consistently hostile to a Conservative Party that is at last looking likely to return to government.1 Much of the criticism originates from the suspicion that the refusal of other centre-right parties in Europe to countenance leaving the EPP has forced the Conservatives into an alliance with partners with whom they have – or at least should have – little in common. We question, or at least qualify, this assumption by looking in more detail at the other members of the ECR. We conclude that, while they are for the most part socially conservative, they are less extreme and more pragmatic than their media caricatures suggest. We also note that such caricatures ignore some interesting incompatibilities within the new group as a whole and between some of its Central and East European members and the Conservatives, not least 1 with regard to their foreign policy preoccupations and their by no means wholly hostile attitude to the European integration project. -

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

“The Readiness Is All,” Or the Politics of Art in Post-Communist Bulgaria

Boika Sokolova and Kirilka Stavreva “The readiness is all,” or the Politics of Art in Post-Communist Bulgaria At some point around the turn of the millennium, even as Bulgaria adopted the dominant ideological discourse of Western democracy, finalized the restitution of land and urban property to pre-World War II owners, carried out large-scale privatization of government assets, and took decisive steps toward Euro-Atlantic integration, its political transition got stuck in the vicious circle of post-communism.1 Post-communism, hardly a condition limited to Bulgaria, we define as a forestalled democratic transition whose ultimate goals of freedom, justice, and economic prosperity have been hijacked. As poet and political activist Edvin Sugarev maintains, most Bulgarians today perceive the “transition to democracy as a territory of crushed hopes,” as “a free fall into philistinism and absurdity . recognized as degradation and experienced as depression.”2 Bulgarian post-communism has generated a façade democracy, marked by a vast divide between the haves and the have-nots, a feeble middle class, pervasive corruption, a devastating demographic crisis, and wide-ranging social apathy and desperation.3 Social stratification has reduced to basic survival a disturbingly large number of Bulgarians. In the 1 Bulgaria joined NATO's Partnership for Peace in 1994, applied for NATO membership in 1997, and was admitted in 2004. In 1995 it formally applied for EU membership and, having met membership conditions, joined the Union in 2007, although it was not granted full working rights until 2012. According to the World Bank, the two-stage mass privatization program (under Videnov’s government in 1995-96 and under Kostov’s, 1998-2000) resulted in 85% of privatization of overall state assets by the end of 2000 (http://www.fdi.net/documents/WorldBank/databases/plink/factsheets/bulgaria.htm). -

The Party System in Bulgaria

ANALYSE DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS The second party system after 1989 (2001-2009) turns out THE PARTY SYSTEM to have been subjected to new turmoil after the Nation- IN BULGARIA al Assembly elections in 2009. 2009-2019 In 2009, GERB took over the government of the country on their own, and their leader Bor- isov was elected prime minister. Prof. Georgi Karasimeonov October 2019 Political parties are a key factor in the consolidation of the democratic political system. FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA 2009-2019 CONTENTS Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. THE ASSERTION OF GERB AS A PARTY OF POWER AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE COALITION OF BSP AND MRF 3 3. THE GOVERNMENT OF THE „BROAD SPECTRUM (MULTI-PARTY) COALITION“ AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR THE PARTY SYSTEM (2014-2017) 9 4. POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE CONTEXT OF SEMI-CONSOLIDATED DEMOCRACY 13 5. CONCLUSION 15 1 FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA 1 INTRODUCTION The second party system after 1989 (2001-2009) was sub- which have become part of European party families. In a ject to new changes after the elections for the National series of reports of the European Union, following the ac- Assembly in 2009. Its lability and ongoing transformation, cession of Bulgaria, harsh criticism has been levied, mainly and a growing crisis of trust among the citizens regarding against unsubjugated corruption and the ineffective judi- the parties, was evident. Apart from objective reasons con- ciary, which undermines not only the confidence of citi- nected with the legacy of the transition from the totalitar- zens in political institutions, but also hinders the effective ian socialist system to democracy and a market economy, use of EU funds in the interest of the socio-economic de- key causes of the crisis of trust in political parties were velopment of the country.