Another Look at Mcclellan's Peninsula Campaign

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection SC 0084 W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection 1862

Collection SC 0084 W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection 1862 Table of Contents User Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Container List Processed by Emily Hershman 27 June 2011 Thomas Balch Library 208 W. Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 USER INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 2 folders COLLECTION DATES: 1862 PROVENANCE: W. Roger Smith, Midland, TX. ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: Collection open for research USE RESTRICTIONS: No physical characteristics affect use of this material. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from Thomas Balch Library. CITE AS: W. Roger Smith Civil War Research Collection, 1862 (SC 0084), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: None ACCESSION NUMBERS: 1995.0046 NOTES: Formerly filed in Thomas Balch Library Vertical Files 2 HISTORICAL SKETCH From its organization in July 1861, the Army of the Potomac remained the primary Union military force in the East, confronting General Robert E. Lee’s (1807-1870) Army of Northern Virginia in a series of battles and skirmishes. In the early years of the Civil War, however, the Army of the Potomac suffered defeats at the Battle of the First Bull Run in 1861, the Peninsula Campaign and the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862, as well as the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Historians attribute its initial lack of victories to poor leadership from a succession of indecisive generals: Irvin McDowell (1818-1885), George McClellan (1826-1885), Ambrose Burnside (1824-1881), and Joseph Hooker (1814-1879). When General George Meade (1815-1872) took command of the Army of the Potomac in June 1863, he was successful in pushing the Army of Northern Virginia out of Pennsylvania following the Battle of Gettysburg. -

The Battle of Sailor's Creek

THE BATTLE OF SAILOR’S CREEK: A STUDY IN LEADERSHIP A Thesis by CLOYD ALLEN SMITH JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2005 Major Subject: History THE BATTLE OF SAILOR’S CREEK: A STUDY IN LEADERSHIP A Thesis by CLOYD ALLEN SMITH JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph Dawson Committee Members, James Bradford Joseph Cerami Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger December 2005 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT The Battle of Sailor’s Creek: A Study in Leadership. (December 2005) Cloyd Allen Smith Jr., B.A., Slippery Rock University Chair: Dr. Joseph Dawson The Battle of Sailor’s Creek, 6 April 1865, has been overshadowed by Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House several days later, yet it is an example of the Union military war machine reaching its apex of war making ability during the Civil War. Through Ulysses S. Grant’s leadership and that of his subordinates, the Union armies, specifically that of the Army of the Potomac, had been transformed into a highly motivated, organized and responsive tool of war, led by confident leaders who understood their commander’s intent and were able to execute on that intent with audacious initiative in the absence of further orders. After Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia escaped from Petersburg and Richmond on 2 April 1865, Grant’s forces chased after Lee’s forces with the intent of destroying the mighty and once feared iv protector of the Confederate States in the hopes of bringing a swift end to the long war. -

1 Longstreet, James. from Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil

Longstreet, James. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020. Hardback: $75.00; Paperback $25.00 . ISBN: 978-0-253-04706-9. Much detail on various commands, and units; much matter of fact accounts and description, often impersonal; good deal of the quoting from the Official records; mild and often indirect in any criticisms of Lee; some sly anti-Jackson comments; much attention to vindicating his performance at Gettysburg; Introduction by James I. Robertson, Jr. 1. Long controversy about Longstreet at Gettysburg 2. Notes Freeman reduced criticism of Longstreet 3. Imposing physically, some deafness, sparse conversation 4. Three children died of scarlet fever early in 1862 5. More dependable than brilliant, not suited for independent command 6. Limited insight but stubbornness 7. Close relationship with Lee 8. Calming influence 9. Favored the defensive 10. Did well at Chickamauga 11. Failure in independent command at Knoxville 12. Ruinous decision to become a Republican 13. Mixed performance at Gettysburg—not good at defending himself after the war 14. Memoir is “unbalanced, critical, and sometimes erroneous,” p. xxiii 15. Mixed record of a dependable general, Lee’s war horse Forward by Christopher Keller ` 1. indispensable narrative about the Army of Northern Virginia 2. praises great eye for detail 3. compares well with Grant’s and Sherman’s memoirs Background, planter’s son, 13 Not much of an academic at West Point, 15-16 Service in regular army, 17ff Mexican War, 19-28 New Mexico, 29-30 Cheering on way to Richmond, 32 Bull Run, Manassas campaign, McDowell and Beauregard criticized, 33-58 Siege of the Potomac, 59ff Richardson invited Longstreet to a dinner party, 59 Skirmishes, 60ff Defenses of Richmond, 64-65 Council of war, Davis, Lee, opinion of McClellan. -

RICHMOND Battlefields UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR Stewart L

RICHMOND Battlefields UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER THIRTY-THREE This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C. Price 25 cents. RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia by Joseph P. Cullen NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 33 Washington, D.C., 1961 The National Park System, of which Richmond National Battlefield Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people. Contents Page Richmond 1 The Army of the Potomac 2 PART ONE THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER 1862 On to Richmond 3 Up the Peninsula 4 Drewry's Bluff 5 Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) 6 Lee Takes Command 9 The Seven Days Begins 12 Beaver Dam Creek (Ellerson's Mill) 13 Gaines' Mill 16 Savage Station 18 Glendale (Frayser's Farm) 21 Malvern Hill 22 End of Campaign 24 The Years Between 27 PART TWO THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR RICHMOND, 1864-65 Lincoln's New Commander 28 Cold Harbor 29 Fort Harrison 37 Richmond Falls 40 The Park 46 Administration 46 Richmond, 1858. From a contemporary sketch. HE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR was unique in many respects. One Tof the great turning points in American history, it was a national tragedy op international significance. -

Confederate Invasions – the Union in Peril Part 1 – the Maryland Campaign: Antietam and Emancipation Class Notes

Confederate Invasions – The Union In Peril Part 1 – The Maryland Campaign: Antietam and Emancipation Class Notes Lecture 2 – “You Are All Green Alike”: Campaigns of 1861-1862 A. Both Sides Mobilize • North has advantages in manpower; manufacturing; and railroad network • South has advantages in 3.5 million slaves; armed state militias; geography • U.S. military has only 15,000 men; 42 ships (only 3 ready on 15 Apr) • Many Southern officers resign, join Confederacy • Lee turns down command of Federal forces; Goes with Virginia B. Political & Military Strategies • Lincoln and Davis – contrasting Commanders-in-Chief • Union Strategy: Scott’s Anaconda Plan – Subdue south with minimum of bloodshed • Southern Strategy: Defend the homeland and erode Union public support • Northern Pressure to Act: On to Richmond C. Eastern Theater – First Manassas; McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign • First Manassas/Bull Run (21 July 1861) – demolishes many myths • Rise of McClellan - “Little Napoleon” • Lincoln forced to become his own general-in-chief • Peninsula Campaign (April-May 1862) – plan to flank Confederate defenses • Army of Potomac, 100,000 strong, advances slowly, cautiously • Battle of Seven Pines – Johnston wounded; Lee assumes command • Jackson’s Valley Campaign – one bright spot for Confederacy D. Western Theater – 1862 Early Union Successes – Grant Emerges • Grant captures Forts Henry & Donelson in February 1861 • Nashville is abandoned by retreating Confederates • Battle of Pea Ridge (8 March): Union victory • Battle of Shiloh (6-7 April): Grant again victorious • New Orleans falls to Admiral Farragut on 25 April • Halleck’s Union forces capture Memphis on 6 June E. Political Dimension • Despite Union successes in the Western Theater, the key to victory in the Civil War is the public’s “will to continue” in the face of mounting costs. -

Civil War Battles, Campaigns, and Sieges

Union Victories 1862 February 6-16: Fort Henry and Fort Donelson Campaign (Tennessee) March 7-8: Battle of Pea Ridge (Arkansas) April 6-7: Battle of Shiloh/ Pittsburg Landing (Tennessee) April 24-27: Battle of New Orleans (Louisiana) September 17: Battle of Antietam/ Sharpsburg (Maryland) October 8: Battle of Perryville (Kentucky) December 31-January 2, 1863: Battle of Stone’s River/ Murfreesboro (Tennessee) 1863 March 29- July 4: Vicksburg Campaign and Siege (Mississippi)- turning point in the West July 1-3: Battle of Gettysburg (Pennsylvania)- turning point in the East November 23-25: Battle of Chattanooga (Tennessee) 1864 May 7-September 2: Atlanta Campaign (Georgia) June 15-April 2, 1865: Petersburg Campaign and Siege (Virginia) August 5: Battle of Mobile Bay (Alabama) October 19: Battle of Cedar Creek (Virginia) December 15-16: Battle of Nashville (Tennessee) November 14-December 22: Sherman’s March to the Sea (Georgia) 1865 March 19-21: Battle of Bentonville/ Carolinas Campaign (North Carolina) Confederate Victories 1861 April 12-14: Fort Sumter (South Carolina) July 21: First Battle of Manassas/ First Bull Run (Virginia) August 10: Battle of Wilson’s Creek (Missouri) 1862 March 17-July: Peninsula Campaign (Virginia) March 23-June 9: Jackson’s Valley Campaign (Virginia) June 25-July 2: Seven Days Battle (Virginia) August 28-30: Second Battle of Manassas/ Second Bull Run (Virginia) December 11-13: Battle of Fredericksburg (Virginia) 1863 May 1-4: Battle of Chancellorsville (Virginia) September 19-20: Battle of Chickamauga (Georgia) -

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park Virginia by Joseph P. Cullen (cover of 1961 edition) National Park Service Historical Handbook Series No. 33 Washington, D.C. 1961 Contents a. Richmond b. The Army of the Potomac PART ONE THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER 1862 c. On to Richmond d. Up the Peninsula e. Drewry's Bluff f. Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) g. Lee Takes Command h. The Seven Days Begins i. Beaver Dam Creek (Ellerson's Mill) j. Gaines' Mill k. Savage Station l. Glendale (Frayser's Farm) m. Malvern Hill n. End of Campaign o. The Years Between PART TWO THE FINAL STRUGGLE FOR RICHMOND, 1864-65 p. Lincoln's New Commander q. Cold Harbor r. Fort Harrison s. Richmond Fall's t. The Park u. Administration For additional information, visit the Web site for Richmond National Battlefield Park Historical Handbook Number Thirty-Three 1961 This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D.C. Price 25 cents The National Park System, of which Richmond National Battlefield Park is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director Richmond, 1858. From a contemporary sketch. THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR was unique in many respects. -

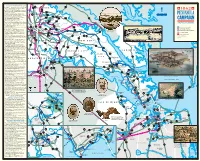

Pen. Map Side

) R ★ MARCH UP THE PENINSULA★ R c a 360 ★ 95 te R Fort Monroe – Largest moat encircled masonry fortifi- m titu 1 Ins o ry A cation in America and an important Union base for t HANOVER o st Hi campaigns throughout the Civil War. o ry P ita P 301 il M P ★ y Fort Wool–Thecompanionfortification to Fort Monroe. m & r A A 2 . The fort was used in operations against Confederate- Enon Church .S g U H f r o held Norfolk in 1861-1862. 606 k y A u s e e t b Yellow Tavern e r ★ r u N Hampton – Confederates burned this port town o s C (J.E.B. Stuart y C to block its use by the Federals on August 7, 1861. k Tot opotomo N c 295 Monument) 643 P i O r • St. John’s Church – This church is the only surviving A C e Old Church K building from the 1861 burning of Hampton. M d Polegreen Church 627 e 606 R • Big Bethel – This June 10, 1861, engagement was r 627 U I F 606 V the first land battle of the Civil War. 628 N 30 E , K R ★ d Bethesda E Monitor-Merrimack Overlook – Scene of the n Y March 9, 1862, Battle of the Ironclads. o Church R I m 615 632 V E ★ Congress and Cumberland Overlook – Scene of the h R c March8,1862, sinking of the USS Cumberland and USS i Cold Harbor R 156 Congress by the ironclad CSS Virginia (Merrimack). -

VILLAGE of DEEP CREEK ★★★ the Dismal Swamp Rangers

VILLAGE OF DEEP CREEK ★★★ The Dismal Swamp Rangers Before you is the Deep Creek Lock to Fort Boykin on Burwell’s Bay until it crossed the James River to serve of the Great Dismal Swamp Canal. in the Confederate Warwick River defenses. The Peninsula Campaign took The canal was an important thor- a toll on this small company of 68 men. At the Battle of Frazer’s Farm oughfare, connecting the North (Glendale) on June 30, 1862, it suffered 22 killed and wounded. One soldier, Carolina Sounds with Hampton Private Maurice Liverman, was mortally wounded during the battle, yet Roads and the Chesapeake Bay. turned to his comrades and said, “Boys, I can’t live much longer, so hold me The Dismal Swamp Canal is up so that I can fire one more shot and kill one more Yankee before I die, the oldest operating artificial water- to get even with them for my own death.” His fellow soldiers complied. The Village of Deep Creek, c. 1890. way in the United States. Construc- The Dismal Swamp Rangers continued to serve in the Army of tion was authorized by the Virginia legislature in 1787 and subsequently by Northern Virginia after the Peninsula Campaign. The unit fought at Second North Carolina in 1790. Both Union and Confederate strategists recognized Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, Dinwiddie Court House, the canal’s importance and sought to control the waterway. and Five Forks. Two members of the Rangers surrendered at Appomattox. One commercial center that grew along the canal during the ante- Passage of Union boats through the Dismal Swamp Canal. -

Strategic Challenges in American Military History

Strategic Challenges in American Military History “This struggle is to save the Union”: Two Approaches to Executing President Lincoln’s Wartime Strategy “He [Lincoln] could think strategically,…Lincoln possessed one of the greatest qualities in leadership: the ability to learn. Able rhetorically to soar above all others in his vision and evocation of the Union, he was also a ruthless pragmatist when it came to measures related to winning the war. He once said in 1862 that he ‘was pretty well cured of any objection to any measure except want of adaptedness to putting down the rebellion.’ His record bears out his words.” Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War Questions for Consideration What do you think Donald Stoker means when he says that “He [Lincoln] could think strategically”? How is this different from thinking at the operational or tactical levels? Why is it so important to have a national leader that can think strategically as opposed to delving in to operational or tactical issues? REFERENCES • Glatthaar, Joseph T. Partners in Command: The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War. New York: Free Press, 1994. • Hsieh, Wayne. “The Strategy of Lincoln and Grant,” in ed. Williamson Murray and Richard Hart Sinnerich, Successful Strategies: Triumphing in War and Peace from Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. • Stoker, Donald. The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. Supplementary: • Blair, Jayne. The Essential Civil War: A Handbook to the Battles, Armies, Navies and Commanders. Jefferson: McFarland and Company, 2006. -

The Decision to Withhold I Corps from the Peninsula Campaign, 1862

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1990 The Unkindest Cut: The Decision to Withhold I Corps from the Peninsula Campaign, 1862 Christianne niDonnell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation niDonnell, Christianne, "The Unkindest Cut: The Decision to Withhold I Corps from the Peninsula Campaign, 1862" (1990). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625628. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a8jx-p093 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE UNKINDEST CUT: THE DECISION TO WITHHOLD I CORPS FROM THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, 1862 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christianne niDonnell 1990 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Christianne niDon Approved, May 19 90 Johnson III Richard B. Sherman C j Q O U i C s r - _______ H. Cam Walker TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................... iv LIST OF FIGURES ...................................... V ABSTRACT .............................................. vi INTRODUCTION .... .................................. 2 CHAPTER I. DOGS OF W A R .............................. 5 CHAPTER II. BESTRIDING THE WORLD .................. -

The Role of Intelligence in the Civil War Part II: Support to Military Operations Lecture Two: Union Intelligence in Transition – Mcclellan, Burnside, Hooker

The Role of Intelligence in the Civil War Part II: Support to Military Operations Lecture Two: Union Intelligence in Transition – McClellan, Burnside, Hooker No Professional Military Intelligence Structure: As we will see, until 1863, neither side created a professional Military Intelligence structure – relying instead on civilians & amateurs. Commanders also tended to do their own analysis. Why?! At that time, the conduct of military intelligence was considered a “ function of command,” which any professional soldier could perform. It did not require any special skills. Like: “Anyone can cook.” MCCLELLAN APPROACH – ARROGANCE & AMATEURS • We saw in Part I, how Allen Pinkerton was hired by Samuel Felton , President of Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore RR to protect Lincoln - which he did. On 21 April (9 days after attack on Ft. Sumter) Pinkerton wrote to Lincoln offering his services to start: “obtaining information on the movements of traitors, or safely convey your letters or dispatches.” Before the President could respond, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan asked Pinkerton to set up a military intelligence service for McClellan’s command – the Division of the Ohio. Pinkerton agreed and, with several detectives, headed for McClellan’s HQ in Cincinnati. Pinkerton remained a civilian, but took a new cover alias – Major E.J. Allen. o Allen Pinkerton Background : Born, Glasgow (1819). Came to U.S. at age 23, worked as deputy sheriff & Chicago policeman. In 1850, founded his own agency. Created early “Detectives Code of Conduct” – “no addiction to drink, smoking, card playing, low dives or…slang.” o The sign on his HQs was a huge eye & company motto: “We Never Sleep.