P0433-P0437.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Innocent ITV Wylie Interviews

Contents Press Release 3 - 4 Foreword by writer and creator Chris Lang 5 Cast Interviews 6 - 11 Episode Synopses 12 - 15 Cast and Production Credits 16 - 17 Back Page 18 2 Lee Ingleby and Hermione Norris lead the cast of new ITV drama serial Innocent Innocent is a new four-part contemporary drama series written by acclaimed writers Chris Lang and Matt Arlidge starring Hermione Norris and Lee Ingleby and produced by TXTV. They are joined by an exciting ensemble cast including Daniel Ryan (Home Fires, Mount Pleasant), Angel Coulby (Merlin, The Tunnel), Nigel Lindsay (Victoria, Foyle’s War), Elliot Cowan (Da Vinci’s Demons, Frankenstein Chronicles) and Adrian Rowlins (Harry Potter, Dickensian). The drama series tells the compelling story of David Collins (Lee Ingleby) who is living a nightmare. Convicted of murdering his wife Tara, David has served seven years in prison. He’s lost everything he held dear: his wife, his two children and even the house he owned. He’s always protested his innocence and faces the rest of his life behind bars. His situation couldn’t be more desperate. Despised by his wife’s family and friends, his only support has been his faithful brother Phil (Daniel Ryan) who has stood by him, sacrificing his own career and livelihood to mount a tireless campaign to prove his brother’s innocence. Convinced of his guilt, Tara’s childless sister Alice (Hermione Norris) and her husband Rob (Adrian Rowlins) are now parents to David’s children. They’ve become a successful family unit and thanks to the proceeds of David’s estate enjoy a comfortable lifestyle, which is very different to when Tara was alive. -

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then a Comparative Thesis on Malory's Le Morte D'arthur and BBC's Merlin Bachelor Thesis Engl

The Arthurian Legend Now and Then A Comparative Thesis on Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur and BBC’s Merlin Bachelor Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Student: Saskia van Beek Student Number: 3953440 Supervisor: Dr. Marcelle Cole Second Reader: Dr. Roselinde Supheert Date of Completion: February 2016 Total Word Count: 6000 Index page Introduction 1 Adaptation Theories 4 Adaptation of Male Characters 7 Adaptation of Female Characters 13 Conclusion 21 Bibliography 23 van Beek 1 Introduction In Britain’s literary history there is one figure who looms largest: Arthur. Many different stories have been written about the quests of the legendary king of Britain and his Knights of the Round Table, and as a result many modern adaptations have been made from varying perspectives. The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend traces the evolution of the story and begins by asking the question “whether or not there ever was an Arthur, and if so, who, what, where and when.” (Archibald and Putter, 1). The victory over the Anglo-Saxons at Mount Badon in the fifth century was attributed to Arthur by Geoffrey of Monmouth (Monmouth), but according to the sixth century monk Gildas, this victory belonged to Ambrosius Aurelianus, a fifth century Romano-British soldier, and the figure of Arthur was merely inspired by this warrior (Giles). Despite this, more events have been attributed to Arthur and he remains popular to write about to date, and because of that there is scope for analytic and comparative research on all these stories (Archibald and Putter). The legend of Arthur, king of the Britains, flourished with Geoffrey of Monmouth’s The History of the Kings of Britain (Monmouth). -

Merlin Season One Trivia Quiz

MERLIN SEASON ONE TRIVIA QUIZ ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> In season one, Merlin arrives in Camelot and is the apprentice to the town's physician. What was his name? a. Uther b. John c. Elyan d. Gaius 2> In episode two, Valiant, what creature is painted on the shield of the knight that is facing Arthur? Hint - The creature(s) come to life. a. Gargoyles b. Demons c. Dragons d. Serpents 3> What is the name of Morgana's servant? a. Hunith b. Morgose c. Nimueh d. Gwen 4> Who was the sorceress responsible for the plaque/sickness that swept Camelot as the result of a dragon egg? a. Morgose b. Sophia c. Mordred d. Nimueh 5> What creature is half eagle and half lion that was seen in episode 5 of Season 1? a. Griffin b. Cyclops c. Hippogriff d. Narvick 6> Which character suffers extreme and terrible nightmares? a. Morgana b. Uther c. Gaius d. Arthur 7> Who tried to replace Gaius as court physician by tricking everyone into thinking he had a "cure all" for any form of sickness? a. Edwin b. Cenred c. Mardan d. Aulfric 8> Who warns Merlin of Mordred? a. Sir Percival b. Morgana c. Gaius d. The Dragon 9> Who killed a unicorn? a. Guinevere b. Merlin c. Uther d. Arthur 10> Which "knight" of Camelot had a forged nobility statement? a. Euan b. Percival c. Lancelot d. Davis 11> Which actor plays the role of Merlin? a. Bradley James b. Richard Wilson c. Rupert Young d. Colin Morgan 12> Which of the following practices is banned by King Uther Pendragon in Camelot? a. -

Three Modern Views of Merlin

Volume 16 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 7-15-1990 Three Modern Views of Merlin Gwyneth Evans Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Gwyneth (1990) "Three Modern Views of Merlin," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 16 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol16/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines the use of Merlin as a character in Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, two novels by J.C. Powys, and Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising series. Notes parallels and differences in Merlin’s power, role, prophetic ability, link with the divine, and vulnerability. Additional Keywords Cooper, Susan. The Dark is Rising (series)—Characters—Merlin; Merlin; Powys, J.C. -

Colorblind" Visibility, and the Narrative Marginalization of Black Female Protagonists in Mainstream Fantasy Media

BUT WE DREAM IN THE DARK FOR THE MOST PART: FANTASIES OF RACE, "COLORBLIND" VISIBILITY, AND THE NARRATIVE MARGINALIZATION OF BLACK FEMALE PROTAGONISTS IN MAINSTREAM FANTASY MEDIA A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English By Bezawit Elsabet Yohannes, B.A. Washington, D.C. March 23, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Bezawit Elsabet Yohannes All Rights Reserved ii BUT WE DREAM IN THE DARK FOR THE MOST PART: FANTASIES OF RACE, "COLORBLIND" VISIBILITY, AND THE NARRATIVE MARGINALIZATION OF BLACK FEMALE PROTAGONISTS IN MAINSTREAM FANTASY MEDIA Bezawit Elsabet Yohannes, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Angelyn L. Mitchell, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Fantastic stories offer new ways of dreaming, yet even in magical worlds race remains the “unspeakable thing unspoken.” My project analyzes the racialization of Black female characters positioned as protagonists in early 2000s mainstream fantasy media, looking primarily at Gwen from BBC’s Merlin, Tiana from Disney’s Princess and the Frog, and Cinderella from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella. By only incorporating Black female actors through “colorblind” casting, writers and producers make Black female characters visible but fail to incorporate the necessary cultural specificity of representation. Consequently, the adaptation of fantasies defined by white cultural values resist the new centrality of the “Dark Other” and instead re-inscribe oppressions of the racial past. These supposedly colorblind narratives of “worlds-that-never-were” cannot divorce historical settings and archetypes from their temporal connotations when applied to a Black female protagonist. -

Santiago Cabrera

Santiago Cabrera Height: 6' 0" [182.88 cm.] Eye Color: Brown Hair Color: Dark brown Training: Drama Centre London SKILLS FOOTBALL (HIGHLY SKILLED), TENNIS, HOCKEY AN ALL ROUND SPORTSMAN PADI SCUBADIVING LANGUAGES: SPANISH, UNACCENTED ENGLISH, FRENCH, ITALIAN ACCENTS: STANDARD AMERICAN, RP FULL CLEAN DRIVING LICENSE *NOMINATED FOR AN ALMA AWARD FOR OUTSTANDING ACTOR IN A TV SERIES, MINI-SERIES OR TV MOVIE BY THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF LA RAZA (NCLR) GREEN CARD HOLDER FILM WHAT HAPPENED TO MONDAY Infomercial Processor Netflix Tommy Wirkola TRANSFORMERS: THE LAST KNIGHT Santos Dreamworks Michael Bay HEMINGWAY & GELLHORN Robert Capa HBO Films Philip Kaufman CRISTIADA Father Vega New Land Films Dean Wright MEANT TO BE Ben Corsan Productions N.V. Paul Breuls CHE: PART ONE Camilo Focus Features Steven Soderbergh CALEUCHE: EL ILLAMADO DEL MAR Simon Angel Films Jorge Olguin GOAL 2: LIVING THE DREAM Diego Rivera Buena Vista Jaume Collett-Serra LOVE & OTHER DISASTERS Paolo Sarmiento Skyline Films Alek Keshishian HAVEN Gene Miramax Frankie Flowers TELEVISION STAR TREK: PICARD Ian CBS Various PRISM Diego Sosa Universal Studios Daniel Barnz TITANS Douglas Lamb Warner Brothers Televison Various SALVATION Darius Tanz (lead) CBS Various BIG LITTLE LIES (2 SEASONS) Joseph Bachman HBO Jean-Marc Vallee THE MINDY PROJECT Diego Universal Television Various THE MUSKETEERS (3 SERIES) Aramis BBC TV Toby Haynes/John Strickland ANNA KARENINA Vronsky Lux Vide Spa Christian Duguy DEXTER Sal Price Showtime Networks Various FALCON (SERIES 1) Judge Esteban Calderon Mammoth -

Starring John Hurt, Sebastian Stan, Jessica Brown-Findlay, Vanessa Kirby, Claudia Gerini with Tony Curran and Tom Felton

THE FACTS Labyrinth has been published in more than thirty-eight languages worldwide. UK Top 5 Bestseller Top 10 Bestseller # 1 Hardback Australia Bulgaria Brazil Finland # 1 Paperback, initial 6 months of release Canada Israel # 1 selling book of 2006 – more than France Poland 1 million copies sold Germany Slovenia India Sweden Winner of ‘Best Read Award’ British Book Awards 2006 Italy Turkey Netherlands United Arab Emirates Picked by Waterstone’s as a top 25 book New Zealand of past 25 years Norway Russia USA South Africa New York Times hardback Turkey bestseller list for 4 weeks New York Times paperback bestseller STARRING JOHN HURT, SEBASTIAN STAN, JESSICA BROWN-FINDLAY, VANESSA KIRBY, CLAUDIA GERINI WITH TONY CURRAN AND TOM FELTON Worldwide Distribution IN ASSOCIATION WITH Sonnenstrasse 14, 80331 Munich, Germany Phone +49 (89) 96 22 83 00 An official German – South African Co-Production © Tandem Productions GmbH & Film Afrika Worldwide (Pty) Limited South Africa. (Pty) Productions GmbH & Film Afrika Worldwide An official German – South African Co-Production © Tandem [email protected] www.studiocanaltvseries.com THE STORY THE KEY CAST She inherits a house in the South of Alice knows that there are people France from an aunt she has never met; willing to kill for whatever is behind she is haunted by dreams of a woman the meaning of the labyrinth she from the past, whom she does not found carved into the wall of a cave. know; and now she stumbles upon an But she must now race to fi nd out archeological fi nd that will bear witness what happened to Alaïs and how she to a genocide committed 800 years ago can prevent the past from recurring. -

MERLIN III Cast Iron Blocks Specifications, Technical Data and Instruction Sheet

MERLIN III Cast Iron Blocks Specifications, Technical Data and Instruction Sheet Part # Bore Size Main Size/Type Deck Height Stage of Readiness 081100 4.245 2.750 Nodular 9.800 Bare Block 081101 4.495 2.750 Nodular 9.800 Bare Block 081102 4.595 2.750 Nodular 9.800 Bare Block 081103 4.245 2.750 Nodular 9.800 Bare Block 1 Piece Seal 081105 4.495 2.750 Nodular 9.800 Bare Block 1 Piece Seal 081107 4.595 2.750 Nodular 9.850 Bare Block 081110 4.245 2.750 Nodular 10.200 Bare Block 081111 4.495 2.750 Nodular 10.200 Bare Block 081112 4.595 2.750 Nodular 10.200 Bare Block 081114 4.495 2.750 Nodular 10.200 Bare Block 1 Piece Seal 081115 4.595 2.750 Nodular 10.200 Bare Block 1 Piece Seal 081117 4.595 2.750 Nodular 10.250 Bare Block 085000 4.245 2.750 Billet Splayed 9.800 Bare Block 085010 4.495 2.750 Billet Splayed 9.800 Bare Block 085012 4.595 2.750 Billet Splayed 9.800 Bare Block 085100 4.245 2.750 Billet Splayed 10.200 Bare Block 085110 4.495 2.750 Billet Splayed 10.200 Bare Block 085112 4.595 2.750 Billet Splayed 10.200 Bare Block Block Applications: The MERLIN III IRON blocks are designed to be a replacement for the Mark IV Big Block Chevy. In applications (either street or race) where the combination is making 1000 plus H.P. normally aspirated or the block is being used in a nitrous or blower application, it is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED to use the Merlin III block with the billet, splayed main caps. -

HOULTON PIONEER TIMES County Tbe Only Newspaper in the World Interested in Houlton, Maine > VOL

Pres* Run 4400 Copies Of Service 2 Sections In Aroostook HOULTON PIONEER TIMES County Tbe Only Newspaper in the World Interested in Houlton, Maine > VOL. 105 NO. 32 Houlton, Maine, Thursday, August 8, 1963 TEN CENTS Aroostook at the Crossroads! Teaching Assignments Filled The Great Marketing Mess Third In a series of articles on the crista facing Maine potato farmers as seen by industry leaders. For All Schools Of SAD 29 attended the 1University W (Editor’s Note — This is the third in a series of e. He has beeni teaching for articles on the Maine potato industry, its problems, its l»ast two years posit ion hopes and its affect on the economy of Aroostook Coun Also approved by the directors ty as seen by thoughtful farmers and business men. The was Ralph Prince for eighth grade math at the junior high. He will Pioneer Times again joins with other weekly news also coach varsity basketball and papers in the County in further appraising the future of baseball, and comes here from a teaching job in Washburn. the potato industry, with particular reference to the Miss Jean Gerry will teach kadvantages many leaders in the industry believe can Grade at Littleton. She is a na- be obtained through widespread adoption of a program ferred from biology to social stu- of centralized marketing.) The Aroostook potato grower has always been a HWC Officials A i gambler. He has to be. Each year he puts literally thousands of dollars into the ground and gambles that Impressed By b he will have a good growing season. -

“In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: the Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Sarah Wente St

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Antonian Scholars Honors Program School of Humanities, Arts and Sciences 4-2013 “In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries Sarah Wente St. Catherine University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/shas_honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wente, Sarah, "“In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic”: The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries" (2013). Antonian Scholars Honors Program. 29. https://sophia.stkate.edu/shas_honors/29 This Senior Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities, Arts and Sciences at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Antonian Scholars Honors Program by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “In a Land of Myth and a Time of Magic” The Role and Adaptability of the Arthurian Tradition in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries By Sarah Wente A Senior Project in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Honors Program ST. CATHERINE UNIVERSITY April 2, 2013 Acknowledgements The following thesis is the result of many months of reading, writing, and thinking, and I would like to express the sincerest gratitude to all who have contributed to its completion: my project advisor, Professor Cecilia Konchar Farr – for her enduring support and advice, her steadfast belief in my intelligence, and multiple gifts of chocolate and her time; my project committee members, Professors Emily West, Brian Fogarty, and Jenny McDougal – for their intellectual prodding, valuable feedback, and support at every stage; Professor Amy Hamlin – for her assistance in citing the images used herein; and my friends, Carly Fischbeck, Rachel Armstrong, Megan Bauer, Tréza Rosado, and Lydia Fasteland – for their constant encouragement and support and for reading multiple drafts along the way. -

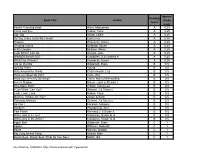

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx.