The Arthurian Legend on the Small Screen Starz’ Camelot and BBC’S Merlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Guinevere

Ingvarsdóttir 1 Hugvísindasvið Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskudeild Queen Guinevere: A queen through time B.A. Thesis Marie Helga Ingvarsdóttir Kt.: 060389-3309 Supervisor: Ingibjörg Ágústsdóttir June 2011 Ingvarsdóttir 3 Abstract This essay is an attempt to recollect and analyze the character of Queen Guinevere in Arthurian literature and movies through time. The sources involved here are Welsh and other Celtic tradition, Latin texts, French romances and other works from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, Malory’s and Tennyson’s representation of the Queen, and finally Guinevere in the twentieth century in Bradley’s and Miles’s novels as well as in movies. The main sources in the first three chapters are of European origins; however, there is a focus on French and British works. There is a lack of study of German sources, which could bring different insights into the character of Guinevere. The purpose of this essay is to analyze the evolution of Queen Guinevere and to point out that through the works of Malory and Tennyson, she has been misrepresented and there is more to her than her adulterous relation with Lancelot. This essay is exclusively focused on Queen Guinevere and her analysis involves other characters like Arthur, Lancelot, Merlin, Enide, and more. First the Queen is only represented as Arthur’s unfaithful wife, and her abduction is narrated. We have here the basis of her character. Chrétien de Troyes develops this basic character into a woman of important values about love and chivalry. -

Now a Major Motion Picture

NOW A MA JOR MOTION PICTURE IN CINEMAS AUGUST 2013 Based on the first book in the international bestselling series by Cassandra Clare City of Bones Starring Lily Collins as Clary Fray Jamie Campbell Bower as Jace Wayland Robert Sheehan as Simon Lewis Kevin Zegers as Alec Lightwood Lena Headey as Jocelyn Fray Kevin Durand as Emil Pangborn Aidan Turner as Luke Garroway Jemima West as Isabelle Lightwood Godfrey Gao as Magnus Bane with CCH Pounder as Madame Dorothea with Jared Harris as Hodge Starkweather and Jonathan Rhys Meyers as Valentine Morgenstern Read the books before you see the film Available in paperback and eBook from all good booksellers Here’s a short taster from City of Bones Clary Fray is seeing things: vampires in Brooklyn and werewolves in Manhattan. Irresistibly drawn towards a group of sexy demon hunters, Clary encounters the dark side of New York City – and the dangers of forbidden love. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. All statements, activities, stunts, descriptions, information and material of any other kind contained herein are included for entertainment purposes only and should not be relied on for accuracy or replicated as they may result in injury. Text © 2007 Cassandra Claire LLC The right of Cassandra Clare to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 This sampler has been typeset in M Garamond All rights reserved. No part of this sampler may be reproduced, transmitted or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, taping and recording, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Summary of the Perlesvaus Or the High History of the Grail (Probably First Decade of 13Th Century, Certainly Before 1225, Author Unknown)

Summary of the Perlesvaus or The High History of the Grail (probably first decade of 13th century, certainly before 1225, author unknown). Survives in 3 manuscripts, 2 partial copies, and one early print edition Percival starts out as the young adventurous knight who did not fulfill his destiny of achieving the Holy Grail because he failed to ask the Fisher King the question that would heal him, events related in Chrétien's work. The author soon digresses into the adventures of knights like Lancelot and Gawain, many of which have no analogue in other Arthurian literature. Often events and depictions of characters in the Perlesvaus differ greatly from other versions of the story. For instance, while later literature depicts Loholt as a good knight and illegitimate son of King Arthur, in Perlesvaus he is apparently the legitimate son of Arthur and Guinevere, and he is slain treacherously by Arthur's seneschal Kay, who is elsewhere portrayed as a boor and a braggart but always as Arthur's loyal servant (and often, foster brother. Kay is jealous when Loholt kills a giant, so he murders him to take the credit. This backfires when Loholt's head is sent to Arthur's court in a box that can only be opened by his murderer. Kay is banished, and joins with Arthur's enemies, Brian of the Isles and Meliant. Guinevere expires upon seeing her son dead, which alters Arthur and Lancelot's actions substantially from what is found in later works. Though its plot is frequently at variance with the standard Arthurian outline, Perlesvaus did have an effect on subsequent literature. -

An Ethnically Cleansed Faery? Tolkien and the Matter of Britain

An Ethnically Cleased Faery? An Ethnically Cleansed Faery? Tolkien and the Matter of Britain David Doughan Aii earlier version of this article was presented at the Tolkien Society Seminar in Bournemouth, 1994. 1 was from early days grieved by the Logres” (p. 369), by which he means a poverty of my own beloved country: it had specifically Arthurian presence. It is most no stories of its own (bound up with its interesting that Lewis, following the confused or tongue and soil), not of the quality 1 sought, uninformed example of Williams, uses the name and found (as an ingredient) in legends of “Logres”, which is in fact derived from Lloegr other lands ... nothing English, save (the Welsh word for England), to identify the impoverished chap-book stuff. Of course Arthurian tradition, i.e. the Matter of Britain! No there was and is all the Arthurian world, but wonder Britain keeps on rebelling against powerful as it is, it is imperfectly Logres. And despite Tolkien's efforts, he could naturalised, associated with the soil of not stop Prydain bursting into Lloegr and Britain, but not with English; and does not transforming it. replace what I felt to be missing. (Tolkien In The Book of Lost Tales (Tolkien, 1983), 1981, Letters, p. 144) Ottor W<efre, father of Hengest and Horsa, also To a large extent, Tolkien is right. The known as Eriol, comes from Heligoland to the mediaeval jongleurs, minstrels, troubadours, island called in Qenya in Tol Eressea (the lonely trouvères and conteurs could use, for their isle), or in Gnomish Dor Faidwcn (the land of stories, their gests and their lays, the Matter of release, or the fairy land), or in Old English se Rome (which had nothing to do with Rome, and uncujm holm (the unknown island). -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Actions Héroïques

Shadows over Camelot FAQ 1.0 Oct 12, 2005 The following FAQ lists some of the most frequently asked questions surrounding the Shadows over Camelot boardgame. This list will be revised and expanded by the Authors as required. Many of the points below are simply a repetition of some easily overlooked rules, while a few others offer clarifications or provide a definitive interpretation of rules. For your convenience, they have been regrouped and classified by general subject. I. The Heroic Actions A Knight may only do multiple actions during his turn if each of these actions is of a DIFFERENT nature. For memory, the 5 possible action types are: A. Moving to a new place B. Performing a Quest-specific action C. Playing a Special White card D. Healing yourself E. Accusing another Knight of being the Traitor. Example: It is Sir Tristan's turn, and he is on the Black Knight Quest. He plays the last Fight card required to end the Quest (action of type B). He thus automatically returns to Camelot at no cost. This move does not count as an action, since it was automatically triggered by the completion of the Quest. Once in Camelot, Tristan will neither be able to draw White cards nor fight the Siege Engines, if he chooses to perform a second Heroic Action. This is because this would be a second Quest-specific (Action of type B) action! On the other hand, he could immediately move to another new Quest (because he hasn't chosen a Move action (Action of type A.) yet. -

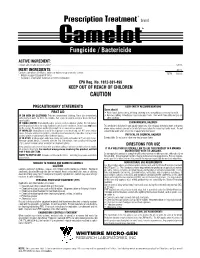

Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide

® Prescription Treatment brand Camelot* Fungicide / Bactericide ACTIVE INGREDIENT: Copper salts of fatty and rosin acids† . 58.0% INERT INGREDIENTS: . 42.0% Contains petroleum distillates, xylene or xylene range aromatic solvent. TOTAL 100.0% † Metallic Copper Equivalent 5.14%) * Camelot is a registered Trademark of Griffin Corporation. EPA Reg. No. 1812-381-499 KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN CAUTION PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS USER SAFETY RECOMMENDATIONS Users should: FIRST AID • Wash hands before eating, drinking, chewing gum, using tobacco or using the toilet. IF ON SKIN OR CLOTHING: Take off contaminated clothing. Rinse skin immediately • Remove clothing immediately if pesticide gets inside. Then wash thoroughly and put on with plenty of water for 15 to 20 minutes. Call a poison control center or doctor for treat- clean clothing. ment advice. IF SWALLOWED: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid This pesticide is toxic to fish and aquatic organisms. Do not apply directly to water, or to areas to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. where surface water is present or to intertidal areas below the mean high water mark. Do not IF INHALED: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambu- contaminate water when disposing of equipment washwaters. lance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice. PHYSICAL OR CHEMICAL HAZARDS IF IN EYES: Hold eye open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15 to 20 minutes. -

Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval Modernist Literature

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval Modernist Literature Shayla Frandsen CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/519 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval and Modernist Literature Shayla Frandsen Thesis Advisor: Paul Oppenheimer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York Table of Contents Preface 1 The Legend of the Fisher King and the Search for the 5 Modern Grail in The Waste Land, Paris, and Parallax “My burden threatens to crush me”: The Transformative Power 57 of the Hero’s Quest in Parzival and Ezra Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley Hemingway, the Once and Future King, 101 and Salvation’s Second Coming Bibliography 133 Frandsen 1 Preface “The riddle of the Grail is still awaiting its solution,” Alexander Krappe writes, the “riddle” referring to attempts to discover the origin of this forever enigmatic object, whether Christian or Folkloric,1 yet “one thing is reasonably certain: the theme of the Frustrated Redemption” (18).2 Krappe explains that the common element of the frustrated redemption theme is “two protagonists: a youth in quest of adventures and a supernatural being . -

The Duke: Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack

™ Arthurian Legends Expansion Pack The politics of the high courts are elegant, shadowy, and subtle. Fort Tile: Players can use the Fort Tile as shown on pages 7-8 of Not so in the outlying duchies. Rival dukes contend for unclaimed the rulebook for any game with these tiles. However, they can also lands far from the king’s reach, and possession is the law in these play with the reverse side of the Fort, Camelot. Camelot is an Ex- lands. Use your forces to adapt to your opponent’s strategies, cap- panded Play tile (see p. 6 of the rulebook) and so both players should turing enemy troops, before you lose your opportunity to seize these agree to its use before play begins. lands for your good. Randomly place Camelot in any square in one of the two middle In The Duke, players move their troops (tiles) around the board rows of the board. and flip them over after each move. Each tile’s side shows a different For the Arthur player, if one of his Arthurian Legends’ tiles is in- movement pattern. If you end your movement in a square occupied side Camelot (King Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, or Merlin), by an opponent’s tile, you capture that tile. Capture your opponent’s then the Camelot Tile gains Command ability in all eight squares Duke to win! surrounding Camelot. On his turn, any time those conditions are met, the player may use the Command ability of Camelot; the Troop ARTHurIan leGenDS EXPanSIon PacK RULES Tile on Camelot does not flip, but the Camelot Tile DOES flip over to Arthur, Guineviere, Merlin, Lancelot and Perceval replace the light the Fort side; as long as it’s on the Fort side, the Command ability no stained Duke, Duchess, Wizard, Champion and Assassin Tiles. -

Introduction: the Legend of King Arthur

Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Professor Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 1 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire with the consent of the author. 2 Department of History University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Abstract of: “HIC FACET ARTHURUS, REX QUONDAM, REXQUE FUTURUS” THE ANALYSIS OF ORIGINAL MEDIEVAL SOURCES IN THE SEARCH FOR THE HISTORICAL KING ARTHUR Final Paper History 489: Research Seminar Professor Thomas Miller Cooperating Professor: Matthew Waters By Erin Pevan November 21, 2006 The stories of Arthurian literary tradition have provided our modern age with gripping tales of chivalry, adventure, and betrayal. King Arthur remains a hero of legend in the annals of the British Isles. However, one question remains: did King Arthur actually exist? Early medieval historical sources provide clues that have identified various figures that may have been the template for King Arthur. Such candidates such as the second century Roman general Lucius Artorius Castus, the fifth century Breton leader Riothamus, and the sixth century British leader Ambrosius Aurelianus hold high esteem as possible candidates for the historical King Arthur. Through the analysis of original sources and authors such as the Easter Annals, Nennius, Bede, Gildas, and the Annales Cambriae, parallels can be established which connect these historical figures to aspects of the Arthur of literary tradition. -

Religion and Religious Symbolism in the Tale of the Grail by Three Authors

Faculty of Arts English and German Philology and Translation & Interpretation COMPARATIVE LITERATURE: RELIGION AND RELIGIOUS SYMBOLISM IN THE TALE OF THE GRAIL BY THREE AUTHORS by ASIER LANCHO DIEGO DEGREE IN ENGLISH STUDIES TUTOR: CRISTINA JARILLOT RODAL JUNE 2017 ABSTRACT: The myth of the Grail has long been recognised as the cornerstone of Arthurian literature. Many studies have been conducted on the subject of Christian symbolism in the major Grail romances. However, the aim of the present paper is to prove that the 15th-century “Tale of the Sangrail”, found in Le Morte d’Arthur, by Thomas Malory, presents a greater degree of Christian coloration than 12th-century Chrétien de Troyes’ Perceval and Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival. In order to evaluate this claim, the origin and function of the main elements at the Grail Ceremony were compared in the first place. Secondly, the main characters’ roles were examined to determine variations concerning religious beliefs and overall character development. The findings demonstrated that the main elements at the Grail Ceremony in Thomas Malory’s “The Tale of the Sangrail” are more closely linked to Christian motifs and that Perceval’s psychological development in the same work conflicts with that of a stereotypical Bildungsroman, in contrast with the previous 12th-century versions of the tale. Keywords: The Tale of the Grail, Grail Ceremony, Holy Grail, Christian symbolism INDEX 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’).