The Ancient Roots of Humor Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Bad Faith

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Gregory Alan Jones for the degree ofMaster ofArts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Philosophy, Philosophy and History presented on May 5, 2000. Title: Racism and Bad Faith. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Leilani A. Roberts Human beings are condemned to freedom, according to Jean-Paul Sartre's Being and Nothingness. Every individual creates his or her own identity according to choice. Because we choose ourselves, each individual is also completely responsible for his or her actions. This responsibility causes anguish that leads human beings to avoid their freedom in bad faith. Bad faith is an attempt to deceive ourselves that we are less free than we really are. The primary condition of the racist is bad faith. In both awarelblatant and aware/covert racism, the racist in bad faith convinces himself that white people are, according to nature, superior to black people. The racist believes that stereotypes ofblack inferiority are facts. This is the justification for the oppression ofblack people. In a racist society, the bad faith belief ofwhite superiority is institutionalized as a societal norm. Sartre is wrong to believe that all human beings possess absolute freedom to choose. The racist who denies that black people face limited freedom is blaming the victim, and victim blaming is the worst form ofracist bad faith. Taking responsibility for our actions and leading an authentic life is an alternative to the bad faith ofracism. Racism and Bad Faith by Gregory Alan Jones A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies Presented May 5, 2000 Commencement June 2000 Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Redacted for privacy Acknowledgment This thesis has been a long time in coming and could not have been completed without the help ofmany wonderful people. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

North American Journal of Psychology, 1999. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 346P.; Published Semi-Annually

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 449 388 CG 029 765 AUTHOR McCutcheon, Lynn E., Ed. TITLE North American Journal of Psychology, 1999. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 346p.; Published semi-annually. AVAILABLE FROM NAJP, 240 Harbor Dr., Winter Garden, FL 34787 ($35 per annual subscription). Tel: 407-877-8364. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT North American Journal of Psychology; vl n1-2 1999 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Psychology; *Research Tools; *Scholarly Journals; *Social Science Research ABSTRACT "North American Journal of Psychology" publishes scientific papers of general interest to psychologists and other social scientists. Articles included in volume 1 issue 1 (June 1999) are: "Generalist Looks at His Career in Teaching: Interview with Dr. Phil Zimbardo"; "Affective Information in Videos"; "Infant Communication"; "Defining Projective Techniques"; "Date Selection Choices in College Students"; "Study of the Personality of Violent Children"; "Behavioral and Institutional Theories of Human Resource Practices"; "Self-Estimates of Intelligence:"; "When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going"; "Behaviorism and Cognitivism in Learning Theory"; "On the Distinction between Behavioral Contagion, Conversion Conformity, and Compliance Conformity"; "Promoting Altruism in Troubled Youth"; The Influence of insecurity on Exchange and Communal Intimates"; "Height as Power in Women"; "Moderator Effects of Managerial Activity Inhibition on the Relation between Power versus Affiliation Motive Dominance and Econdmic Efficiency"; -

Laughter: the Best Medicine?

Laughter: The Best Medicine? by Barbara Butler elcome to a crash COLI~SCin c~onsecli1~11cc.~ol'nvgarivc emotions. Third, Oregon Institute ofMarine Biology Gelotology 101. That isn't a using Iiumor as :I c~ol)irigs(r:itcgy n~ayalso University of Oregon typo, Gelotology (from the I~enefithealth inclirec.tly I)y moderating ad- Greek root gelos (to laugh)), is a term verse effects of stress. Finally, humor may coined in 1964 by Dr. Edith Trager and Dr. provide another indirect Ixnefit to health W.F. Fry to describe the scientific study of by increasing one's level of social support laughter. While you still can't locate this (Martin, 2002, 2004). term in the OED, you can find it on the Web. The study of humor is a science, The physiology of humor and laughter researchers publish in the Dr. William F. Fry from Stanford University psychological and physiological literature has published a number of studies of the as well as subject specific journals (e.g., physiological processes that occur dur- Humor: International Journal of Humor ing laughter and is often cited by people Research). claiming that laughter is equivalent to ex- While at the Special Libraries As- ercise. Dr. Fry states, "I believe that we do sociation annual conference last June, I not laugh merely with our lungs, or chest was able to attend a session by Elaine M. muscles, or diaphragm, or as a result of a Lundberg called Laugh For the Health of stimulation of our cardiovascular activity. It. The room was packed and she had the I believe that we laugh with our whole audience laughing and learning for the physical being. -

Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking As an Outlet for Aggression. John W

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking as an Outlet for Aggression. John W. Dresser Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Dresser, John W., "Two Studies on the Social Function of Joking as an Outlet for Aggression." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1243. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1243 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO STUDIES ON THE SOCIAL FUNCTION OF JOKING AS AN OUTLET FOR AGGRESSION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Psychology by John W. Dresser B.A., Pomona College, 1958 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1962 January, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to express his deep appreciation to his major professor, Dr. Robert N. Vidulich, for his advice and en couragement throughout the course of this research, and for his confidence and generous support throughout the author's doctoral program. Particular thanks are also due Dr. Roland L. Frye for his advice on statistical aspects of the present research. A very special appreciation is owed the author's wife, Mrs. -

The Absurd Author(S): Thomas Nagel Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. The Absurd Author(s): Thomas Nagel Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 68, No. 20, Sixty-Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division (Oct. 21, 1971), pp. 716-727 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2024942 . Accessed: 19/08/2012 01:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org 7i6 THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY The formerstands as valid only if we can findcriteria for assigning a differentlogical formto 'allegedly' than to 'compulsively'.In this case, the criteriaexist: 'compulsively'is a predicate, 'allegedly' a sentenceadverb. But in countless other cases, counterexamplesare not so easily dismissed.Such an example, bearing on the inference in question, is Otto closed the door partway ThereforeOtto closed the door It seems clear to me that betterdata are needed beforeprogress can be made in this area; we need much more refinedlinguistic classificationsof adverbial constructionsthan are presentlyavail- able, ifour evidenceconcerning validity is to be good enough to per- mit a richerlogical theory.In the meantime,Montague's account stands: thereis no reason to thinka morerefined theory, if it can be produced, should not be obtainable within the frameworkhe has given us. -

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler

The Note−Books of Samuel Butler Samuel Butler The Note−Books of Samuel Butler Table of Contents The Note−Books of Samuel Butler..........................................................................................................................1 Samuel Butler.................................................................................................................................................2 THE NOTE−BOOKS OF SAMUEL BUTLER...................................................................................................16 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................................17 BIOGRAPHICAL STATEMENT...............................................................................................................20 I—LORD, WHAT IS MAN?.......................................................................................................................24 Man........................................................................................................................................................25 Life........................................................................................................................................................26 The World..............................................................................................................................................27 The Individual and the World................................................................................................................28 -

The Suspension of Seriousness

CHAPTER ONE Matters of Life and Death And López Wilson, astigmatic revolutionist come to spy upon his enemy’s terrain, to piss on that frivolous earth and be eyewit- ness to the dying of capitalism while at the same time enjoying its death-orgies. —Carlos Fuentes, La región más transparente (1958) Introduction wentieth-century Mexican philosophy properly considered boasts Tof a number of great thinkers worthy of inclusion in any and all philosophical narratives. The better known of these, Leopoldo Zea, José Vasconcelos, Antonio Caso, Samuel Ramos, and, to a great extent, Octavio Paz, have received their fair share of attention in the United States over the last fifty years, partly due to a concerted effort by a few philosophy professors in the US academy who find it necessary to dis- combobulate the Eurocentric philosophical canon with outsiders. For reasons which I hope to make clear in what follows, Jorge Portilla is not one of these outsiders to which attention has been paid—even in his homeland, where he is more likely to be recognized, not as one of Mex- ico’s most penetrating and attuned minds, but rather by his replicant, López Wilson, a caricature of intelligence and hedonism immortalized by Carlos Fuentes in his first novel. This oversight is unfortunate, since Portilla is by far more outside than the rest; in fact, the rest find approval precisely because they do not stray too far afield, keeping to themes and methodologies in tune with the Western cannon. One major reason for 1 2 The Suspension of Seriousness the lack of attention paid to Portilla has to do with his output, restricted as it is to a handful of essays and the posthumously published text of his major work, Fenomenología del relajo. -

The Incongruity of Incongruity Theories of Humor

THE INCONGRUITY OF INCONGRUITY THEORIES OF HUMOR Tomáš Kulka ABSTRACT: The article critically reviews the Incongruity Theory of Humor reaching the conclusion that it has to be essentially restructured. Leaving aside the question of scope, it is shown that the theory is inadequate even for those cases for which it is thought to be especially well suited – that it cannot account either for the pleasurable effect of jokes or for aesthetic pleasure. I argue that it is the resolution of the incongruity rather than its mere apprehension, which is that source of the amusement or aesthetic delight. Once the theory is thus restructured, the Superiority Theory of Humor and the Relief Theory can be seen as supplementary to it. KEYWORDS: Humor, Resolution of Incongruity Socrates: And when we laugh ... do we feel pain or pleasure? Protarchus: Clearly we feel pleasure. (Plato, Philebus, 50) In the literature on humor and laughter it is customary to distinguish between three classical theories: The Superiority Theory (Plato, Aristotle, Hobbes), the Relief Theory (Spencer, Freud) and the Incongruity Theory (Cicero, Kant, Schopenhauer, Kierkegaard).1 The three theories are usually seen as rivals, competing for the most plausible answers to ques- tions like: „Why do we laugh?“, „What is the nature of humor?“, or „What does the comical consist of?“ The Superiority Theory says that the comical is perceived as inferior and our laughter is an expression of the sudden realization of our superiority. The Relief Theory emphasizes the liberating effect of humor. Laughter is seen as a discharge of surplus energy which alleviates psy- chic tension. -

On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word Count: 21991

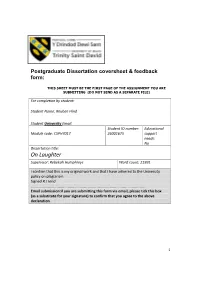

Postgraduate Dissertation coversheet & feedback form: THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by student: Student Name: Reuben Hind Student University Email: Student ID number: Educational Module code: CSPH7017 26001675 support needs: No Dissertation title: On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word count: 21991 I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed R J Hind …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Email submission:if you are submitting this form via email, please tick this box (as a substitute for your signature) to confirm that you agree to the above declaration. 1 ABSTRACT. Much of Western Philosophy has overlooked the central importance which human beings attribute to the Aesthetic experiences. The phenomena of laughter and comedy have largely been passed over as “too subjective” or highly emotive and therefore resistant to philosophical analysis, because they do not easily lend themselves to the imposition of Absolutist or strongly theory-driven perspectives. The existence of the phenomena of laughter and comedy are highly valued because they are viewed as strongly communal activities and expressions. These actually facilitate our experiences as inherently social beings, and our philosophical understanding of ourselves as beings, who experience passions and life itself amidst a world of fluctuating meanings and human drives. I will illustrate how the study of “Aesthetics” developed from Ancient Greek conceptions, through the post-Kantian and post-Romantic periods, which opened-up a pathway to the explicit consideration of the phenomena of laughter and comedy, with particular reference to the Apollonian/Dionysian conceptual schemata referred to in Nietzsche’s early works. -

Role of Humor in Emotion Regulation: Differential Effects of Adaptive and Maladaptive Forms of Humor

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Role of Humor in Emotion Regulation: Differential Effects of Adaptive and Maladaptive Forms of Humor Lindsay Mathews The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1507 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ROLE OF HUMOR IN EMOTION REGULATION: DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS OF ADAPTIVE AND MALADAPTIVE FORMS OF HUMOR by Lindsay M. Mathews A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 i © 2016 LINDSAY M. MATHEWS All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Peggilee Wupperman, Ph.D._______ _________________ ______________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Richard Bodnar, Ph.D. _________________ Date Executive Officer William Gottdiener, Ph.D. Andrew Shiva, Ph.D. David Klemanski, Psy.D. Maren Westphal, Ph.D. Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract ROLE OF HUMOR IN EMOTION REGULATION: DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS OF ADAPTIVE AND MALADAPTIVE FORMS OF HUMOR by Lindsay M. Mathews Advisor: Professor Peggilee Wupperman Humor is widely believed to be an adaptive method of regulating emotions; however, the empirical literature remains inconclusive. -

Voltaire's Candide

CANDIDE Voltaire 1759 © 1998, Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for scholarly or educational purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1.....................................................................................1 How Candide Was Brought Up in a Magnificent Castle and How He Was Driven Thence CHAPTER 2.....................................................................................3 What Befell Candide among the Bulgarians CHAPTER 3.....................................................................................6 How Candide Escaped from the Bulgarians and What Befell Him Afterward CHAPTER 4.....................................................................................8 How Candide Found His Old Master Pangloss Again and What CHAPTER 5...................................................................................11 A Tempest, a Shipwreck, an Earthquake, and What Else Befell Dr. Pangloss, Candide, and James, the Anabaptist CHAPTER 6...................................................................................14 How the Portuguese Made a Superb Auto-De-Fe to Prevent Any Future Earthquakes, and How Candide Underwent Public Flagellation CHAPTER 7...................................................................................16 How the Old Woman Took Care Of Candide, and How He Found the Object of