Submissions Analysis Tahr Control Operational Plan 2020/2021 Reconsideration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Practice of Hunting As a Way to Transcend Alienation from Nature

The Journal of Transdisciplinary Environmental Studies vol. 17, no. 1, 2019 The Practice of Hunting as a Way to Transcend Alienation from Nature Lara Tickle, Ph.D. scholar Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) Division of Environmental Communication Department of Urban and Rural Development Postal address: P.O. Box 7012, SE-750 07 Uppsala, SWEDEN Visiting and delivery address: Ulls väg 28, SE-756 51 Uppsala, SWEDEN Telephone: +46 (0) 186 725 88 Abstract: This paper explores whether and to what extent the practice of leisure hunting is used as a way to transcend the human-nature alienation and thereby reconcile modern society and nature. The study is based on semi-structured interviews with hunters around Stockholm, Sweden and participant observation. In the paper, modernity is discussed from a Marxist perspective as causing the alienation of human beings from nature and natural sources of production through processes of industrialisation, capitalism and urbanisation. By exploring hunting as an ancient activity in a modern society the paper further discusses whether hunting can, through managing and harvesting wildlife, offer some kind of insight into people’s interaction with natural sources of production. The question is whether hunting has the potential to facilitate a more profound appreciation of wildlife and ecosystems by reconnecting people with nature. The effects of Modernity on hunting are also discussed to reflect some of the paradoxes and internal contradictions that exist within hunting. Keywords: Hunting, Alienation, Reconciliation, Modernity, Nature Introduction The first question that led to this project is “why monetize value and separate producers from con- would modern people want to hunt?”. -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

My Sister Is Vegetarian, but I Hunt by Kayci M., Age 16

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF SCI CHAPTERS IN WISCONSIN AND ILLINOIS JULY/AUGUST 2020 My Sister is Vegetarian, But I Hunt by Kayci M., age 16 • Education: R3 Youth Turkey • Humanitarian: COVID Time to Decide • Hunters’ Rights Updates • Chapter News & Events • Who is True Conservationist 18 ACRES...NOTHIN’ BUT ARCHERY Proud HUNTERSOfficial Magazine of SCI Chapters in Wisconsin and Illinois Supporter of: July/August 2020 Editor/Publishers: Mark & Coni LaBarbera On the cover: Kayci Martensen became a successful young hunter while her sister became a vegetarian. Kayci’s deer story starts on page 16. HUNTERS is a bimonthly publication for members of SCI chapters in Wisconsin, 5 Legislative Update plus bonus electronic circulation, which by Dan Trawicki, SCI Lobbyist includes some of the world’s most avid and affluent conservationists who enjoy 6 SCI Region 16 Report hunting here and around the world. They by Regional Rep. Charmaine Wargolet have earned a reputation of leadership on natural resources issues and giving to pro- 6 Safe for Sale tect and support the future of hunting and 7 Mom & Son Success conservation here and abroad. To share by Tiffany Bielenberg Kramer your message with them, send ads and editorial submissions to Mark LaBarbera at 8 Boar-dom Beats Covid Boredom [email protected]. by Mark LaBarbera Submission of story and photos means that 9 Illinois & Chicago Chapter Report you are giving SCI permission to use them 9 Nominate Trailblazer free in SCI printed or electronic form. 10 Badgerland Chapter Report Issue Deadline__ by President Randy Mayes January/February November 20 March/April January 20 10 Legislative: Canadian Gun Ban May/June March 20 10 Small, LaBarbera Win Awards July/August May 20 September/October July 20 11 Wisconsin Chapter Report THE MIDWEST’S PREMIER ARCHERY FACILITY November/December September 20 by President Fred Spiewak New Advertisers 12 Northeast Wisconsin Chapter Report The number of advertisers allowed in WI by President Marty Witczak SCI HUNTERS magazine is limited. -

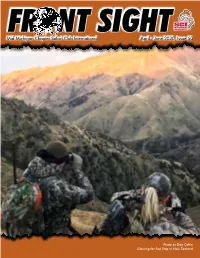

June 2020, Issue 50

FRONT SIGHT MID-MICHIGAN CHAPTER Mid-Michigan Chapter Safari Club International April - June 2020, Issue 50 Photo by Dan Catlin Glassing for Red Stag in New Zealand SAFARIS SOUTH AFRICA ZIMBABWE MOZAMBIQUE WWW. JP SAFARIS.CO.ZA [email protected] FR NT SIGHT In This Issue - April - June 2020 Standing Committees Chairmen are listed first 2 Chapter Officers and Board Members 3 President’s Message Chapter Record Book - Mary Browning 3 Editor’s Message Conservation/Govt. Affairs - Mary Browning 3 Meeting and Events Schedule Dispute Resolution - Abbe Mulders, Kevin Unger, Jon Zieman 4 Book Review — by Josh Christensen Matching Grants - Jon Zieman Journal of a Trapper — by Osborne Russell 5 Trophy Awards Program Front Sight Publication/Advertising - Mary Harter, Don Catlin 6 - 7 Big Buck Night 2020 Education - Doug Chapin 8 - 9 2020 National Convention - Reno, NV Membership - Abbe Mulders 10 National Convention Award - Larry Higgins Nominating - Kevin Unger, Jon Zieman, 11 80 Yr Old Arrows Buck - by Robert C. Mills Abbe Mulders, Janis Ransom 12 - 13 Bird Hunting at Meemo’s - by Mary Harter Programs for Membership Meetings - Doug Chapin 14 - 15 Hunting in New Zealand - by Dan Catlin Big Buck Night - Mike Strope, Kevin Unger, Scott Holmes 16 - 19 Goats at 55? - by Bob Blazer 20 - 21 Last Minute Trophy - by Roger Card Annual Awards Banquet/Fundraiser - Abbe and Joe Mulders, Kevin Unger, and all board members 22 - 23 Thank You for Sponsorship at AWLS - by Katrina Spry & Sarah Westervelt Outfitter Donations - Roger Froling, Mike Strope, Scott Holmes, Kevin Unger, Joe Mulders 24 - 25 Grand Slam - by Tim Torpey 26 - 32 Advertisers Raffles - Doug Chapin Public Relations and Marketing - Kevin Chamberlain Shooting Sports - Tim Schafer Humanitarian Services - Mike Strope Sportsman Against Hunger - Mike Strope Pathfinder Hunts - Brandon Jurries Youth - Disabled Veterans - Blue Bags, etc. -

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry CIV-2010-485 in the Matter of Judicature Amendment Act 1972 and New Zealand

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry CIV-2010-485 In the matter of Judicature Amendment Act 1972 AND New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 AND Animal Welfare (Commercial Slaughter) Code of Welfare 2010 AND Animal Welfare (Commercial Slaughter) Code of Welfare 2002 BETWEEN AUCKLAND HEBREW CONGREGATION TRUST BOARD – a Charitable trust incorporated on 17 January 1955 under Part II of the Religious Charitable and Educational Trusts Act 1908 now known as the Charitable Trusts Act 1957 First plaintiff AND THE WELLINGTON JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTRE – a Charitable Trust incorporated on 4 March 1986 under the Charitable Trusts Act 1957 Second plaintiff AND MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE Defendant Submissions of proposed intervenor The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty in support of plaintiffs Dated: 24 November 2010 2 MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT: INTRODUCTION Interest of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty 1. The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty is a non-profit, nongovernmental, international law firm dedicated to protecting the practice of all religious traditions. It has represented agnostics, Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Native Americans, Santeros, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians, among others, in lawsuits around the world. It is frequently involved, both as counsel of record, and as amicus curiae , in cases seeking to preserve universal religious liberty: the freedom of all religious people to pursue their beliefs without undue government interference. 2. The Becket Fund has represented a wide variety of groups whose religious convictions have come into conflict with government regulation. In France, the Becket Fund advised Sikh students in their case before the Conseil d’État and the European Court of Human Rights. -

1 ANIMALS, SPORT, and the ENVIRONMENT Kass Gibson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Plymouth Marjon University Repository ANIMALS, SPORT, AND THE ENVIRONMENT Kass Gibson 1 Purpose – To outline the multiple ways in which animals are inserted into sporting practices, outline historical and contemporary approaches to studying human-animal sporting practices, and advocate for the centring of sociological problems in human- animal research in sporting contexts and cultures and for considering such problems in relation to environmental issues. Design/methodology/approach -- In the first part of the chapter, conceptual differentiation of animals in the animal-sport complex is presented. Subsequently, studies of interspecies sport are reviewed with reference to the ‘animal turn’ in the literature. In the second part, a critique is presented relating to: i) the privileging of companion animals, especially dogs and horses, which overlooks the multiple ways animals are integrated into (multispecies) sport; ii) micro-sociological and insider ethnographies of companionship displacing of sociological problems in favour of relationship perspectives; and iii) the environment as absent from analysis. The conclusion offers implications for understanding multispecies sport and the environment. Findings -- I chart a general shift in emphasis and focus from animals as an ‘absent- presence’ in pursuit of sociological knowledge towards a clearly defined focus on interspecies sport as a field of research characterised by investigations of relationships with companion animals through the ‘animal turn.’ Research limitations/implications – The focus on companion species means other animals (i.e., non-companions) are understudied, big picture sociological questions are often side-lined, environmental concerns marginalised, and sociological understanding of the environment more generally is either ignored or reduced to a conduit of human-animal interactions. -

Hunting with the Kiwis

HUNTING WITH THEKIWIS First-time hunting experiences are always filled with INVITED GUEST excitement and anticipation. However, when international travel is involved, these hunts can also be intimidating. CYNDY BOYCE HF STAFF We’ve asked the team at Link’s Wild Safaris to provide REMARKS our members some insight into the hunting opportunities LINK’S WILD SAFARIS and logistics of traveling to destinations around the world, and Link’s General Manager, Cyndy Boyce, is starting off GENERAL MANAGER with New Zealand. HUNTING IN NEW ZEALAND Strong populations of chamois, fallow to match every hunter’s budget. New The South Pacific is its own special place deer, red deer, rusa deer, sambar Zealand is the perfect destination for and a sweet spot for many hunters. deer, sika deer, wapiti, whitetail deer, a couple, family, or group of hunters New Zealand is divided into two main pigs, and Himalayan tahr are dispersed where hunts can be accomplished islands, each with a diverse climate, throughout the islands. Additionally, in as few as five days. However, to topography, and scenery. The South there are multiple species of ducks successfully harvest multiple species, Island is home to the infamous Southern and some of the best fly-fishing in the 10-14 days is highly recommended. Alps mountain range and contains 18 world. There is speculation that there March, April, and May provide the peaks over 9,800 feet, with the highest may even be Canadian moose that best months to hunt, and rifle and being Mount Cook at 12,316 feet. The have survived since their introduction archery opportunities are readily less mountainous North Island is the in Fiordland in 1910. -

Recreational Game Hunting: Motivations, Satisfactions and Participation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lincoln University Research Archive Amelia Woods Geoffrey N. Kerr Report No. 18 ____ --- LE P LAND ENVIRONMENT & PEOPLE Recreational Game Hunting: Motivations, Satisfactions and Participation Amelia Woods Geoffrey N. Kerr Land Environment and People Research Report No. 18 June 2010 ISSN 1172‐0859 (Print) ISSN 1172‐0891 (Online) ISBN 978‐0‐86476‐235‐1 Lincoln University, Canterbury, New Zealand Recreational Game Hunting: Motivations, Satisfactions and Participation Reviewed by: Mr Bob Gidlow ©LEaP, Lincoln University, New Zealand 2008 This information may be copied or reproduced electronically and distributed to others without restriction, provided LEaP, Lincoln University is acknowledged as the source of information. Under no circumstances may a charge be made for this information without the express permission of LEaP, Lincoln University, New Zealand. Series URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10182/580 Recreational Game Hunting: Motivations, Satisfactions and Participation Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures.............................................................................................................................. ii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. -

Ethics and Hunting in New Zealand Author(S)

Title: More than Murder: Ethics and Hunting in New Zealand Author(s): Kass Gibson Copyright, publisher and additional information: Manuscript has been published in a journal issue. Pre-print author manuscript version reprinted, by permission, from Sociology of Sport Journal, 2014, 31 (4): 455-474, https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0106. © Human Kinetics, Inc. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0106 Reference: Gibson, K. (2014). More than murder: ethics and hunting in New Zealand, Sociology in Sport Journal, 31(4), 455-474, https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0106 Author pre-print version, there may be minor changes in the final version Gibson, K. ‘More than murder: Ethics and hunting in New Zealand.’ Sociology of Sport Journal, (31)4: 455-474. More Than Murder: Ethics and Hunting in New Zealand Kass Gibson University of St. Mark & St. John In this article I examine the practice of hunting in New Zealand with particular reference to the ways in which hunters make sense of hunting, the embodied experience of hunting, and the moral status of animals. Drawing on ethnographic and interview data I reflect on how the practice and understanding of hunting is guided by a form of relational ethics. As such, the social and historical development of hunting in New Zealand and meaningful connections made with the environment and animals developed through the practice of hunting work to guide hunter’s ethical perspectives rather than any universalized philosophical principles or rules. I argue that by hunting, hunters recognize and consciously engage with multiple standpoints and interests in the backcountry environment in a manner that presents particular challenges to critical studies of human-animal interactions that are frequently unable to look past hunting as killing. -

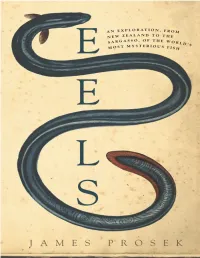

Eels, in Fact, That the Marsh Contained

An Exploration, from New Zealand to the Sargasso, of the World’s Most Amazing and Mysterious Fish James Prosek Thousands passed the lighthouse that night, on the first lap of a far sea journey—all the silver eels, in fact, that the marsh contained. And as they passed through the surf and out to sea, so also they passed from human sight and almost from human knowledge. — RACHEL CARSON, 1941 Contents Cover Title Page Introduction: A Transition in Mind to Eels chapter one: A Mysterious Fish chapter two: To the Sargasso chapter three: Eels in Maoridom chapter four: More Tales of Taniwha chapter five: The First Taste of Freshwater chapter six: Into the Ocean chapter seven: Where Eels Go to Die chapter eight: Eel Weir Hollow chapter nine: The Lasialap of U chapter ten: Obstacles in Their Path chapter eleven: Still in the Hunt Acknowledgments Also by James Prosek Copyright About the Publisher — Introduction — A TRANSITION In Mind to Eels My wall of eel spears he eel is not an easy fish to like. It doesn’t have the beauty of the trout or Tthe colors of the sunfish. As kids, my friends and I caught eels by accident while casting for something else. Unable to grip their muscular, slimy bodies, we stunned them with a smack on the riverbank, then pinned them down with our heels just long enough to remove our hooks from their mouths. We threw them back in the water and watched, astonished, as they swam away. Eels pulsed through my New England upbringing, there and then not there. -

Heterogeneity Amongst New Zealand Hunters

What’s your game? Heterogeneity amongst New Zealand hunters Geoffrey N Ke r r & Walt Abell Lincoln University, Canterbury, NZ Paper presented at the 2014 NZARES Conference Tahuna Conference Centre, Nelson, New Zealand. August 28-29, 2014 Copyright by author(s). Readers may make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes only, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies What’s your game? Heterogeneity amongst New Zealand hunters Geoffrey N. Kerr & Walt Abell Lincoln University ABSTRACT The introduction of the New Zealand Game Animal Council in 2014 heralds a new era for New Zealand big game management. Now that management of game animals to enhance benefits from sustained use is possible, it is important to understand who values game resources and the attributes that enhance benefits from their use. Choice experiments using a pivot design around actual travel distance identified salience of hunt-related attributes for recreational hunters of Himalayan tahr (Jemlahicus Hemitragus) and sika deer (Cervus Nippon). The choice experiments successfully used travel distance as the numeraire of value to overcome resistance to the commodification of hunting. Results show the high value of recreational hunting, and identify disparate preferences both within and between species. Understanding heterogeneity offers important insights into managing hunting experiences to enhance their value for recreational hunters. KEYWORDS Choice experiment, sika deer, Himalayan tahr, recreation, hunting, management, heterogeneity Contributed paper presented at the NZARES Annual Conference, Nelson, 28-29 August 2014. INTRODUCTION The Game Animal Council Act 2013 (The Act) became operative in May 2014, creating the opportunity to manage large game animals to enhance economic and recreational benefits within environmental constraints. -

Domestic Dogs of the Ancient South Pacific

Annual Research & Review in Biology 25(2): 1-11, 2018; Article no.ARRB.40377 ISSN: 2347-565X, NLM ID: 101632869 What We Have Lost: Domestic Dogs of the Ancient South Pacific Carys Louisa Williams1, Silvia Michela Mazzola2*, Giulio Curone2 and Giovanni Quintavalle Pastorino2,3 1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London, NW1 4RY, United Kingdom. 2Department of Veterinary Medicine, Università degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy. 3Faculty of Life Sciences, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author CLW designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors SMM and GQP managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/ARRB/2018/40377 Editor(s): (1) George Perry, Dean and Professor of Biology, University of Texas at San Antonio, USA. Reviewers: (1) Robin Cook, South Africa. (2) Tamer Çağlayan, Selcuk University, Turkey. (3) El Mahdy Cristina, University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca, România. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/23786 Received 7th January 2018 Accepted 19th March 2018 Review Article rd Published 23 March 2018 ABSTRACT In the thousands of years that followed dog domestication, wherever humans went, dogs surely followed. However, the tale of the dog in the ancient South Pacific is often an overlooked one. A small, bandy-legged dog, seemingly not much use for anything but food, this canine could easily be overshadowed in history by more accomplished breeds; the sled dogs of Siberia, the sight hounds of the Middle East, the herders and guarders of Europe, or the practical retrievers of North America.