Domestic Dogs of the Ancient South Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Water Spaniel

V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 1 American Water Spaniel Breed: American Water Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: United States First recognized by the AKC: 1940 Purpose:This spaniel was an all-around hunting dog, bred to retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground with relative ease. Parent club website: www.americanwaterspanielclub.org Nutritional recommendations: A true Medium-sized hunter and companion, so attention to healthy skin and heart are important. Visit www.royalcanin.us for recommendations for healthy American Water Spaniels. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 2 Brittany Breed: Brittany Group: Sporting Origin: France (Brittany province) First recognized by the AKC: 1934 Purpose:This spaniel was bred to assist hunters by point- ing and retrieving. He also makes a fine companion. Parent club website: www.clubs.akc.org/brit Nutritional recommendations: Visit www.royalcanin.us for innovative recommendations for your Medium- sized Brittany. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 4 Chesapeake Bay Retriever Breed: Chesapeake Bay Retriever Group: Sporting Origin: Mid-Atlantic United States First recognized by the AKC: 1886 Purpose:This American breed was designed to retrieve waterfowl in adverse weather and rough water. Parent club website: www.amchessieclub.org Nutritional recommendation: Keeping a lean body condition, strong bones and joints, and a keen eye are important nutritional factors for this avid retriever. Visit www.royalcanin.us for the most innovative nutritional recommendations for the different life stages of the Chesapeake Bay Retriever. V0508_AKC_final 9/5/08 3:20 PM Page 5 Clumber Spaniel Breed: Clumber Spaniel Group: Sporting Origin: France First recognized by the AKC: 1878 Purpose:This spaniel was bred for hunting quietly in rough and adverse weather. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

The Pet Buyer's Guide to Finding a Golden Retriever

The Pet Buyer’s Guide to Finding a Golden Retriever By Cheryl Minnier Your Search Begins… The Golden Retriever is the 2nd most popular breed according to the American Kennel Club. That means that everyday people begin their search for a Golden Retriever who can become a healthy, stable member of their family. However, finding that puppy is not as easy as it once was. The days of opening the newspaper or stopping at a roadside sign and finding the dog of your dreams are long past. This article can help you make more informed decisions about finding a puppy. Today several problems plague our canine friends and any breed that reaches a certain level of popularity will face many challenges. Whenever it appears that there is money to be made breeding dogs, there will be people who will do it without the knowledge, skill and dedication that it takes to produce quality dogs. This can lead to puppies being born that have physical and/or temperament problems that make them unsuitable for family companionship. It can also lead to poor placement of puppies that results in adult dogs needing new homes. To maximize your chances of finding a wonderful companion, it is recommended that you purchase a puppy from a responsible breeder or consider an adult rescue dog. Problems, What Problems? .… Goldens should be healthy, stable dogs but unfortunately there are several problems that can occur. Among them are: Canine Hip Dysplasia (CHD) and Elbow Dysplasia (ED) CHD is a malformation of the hip joint that can cause pain and lameness. -

Ranked by Temperament

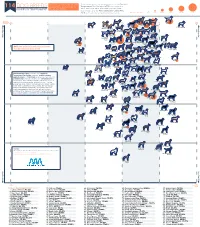

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally Active and Alert, Sporting Dogs Make Likeable, Well-Rounded Companions

Sporting Group Study Guide Naturally active and alert, Sporting dogs make likeable, well-rounded companions. Remarkable for their instincts in water and woods, many of these breeds actively continue to participate in hunting and other field activities. Potential owners of Sporting dogs need to realize that most require regular, invigorating exercise. The breeds of the AKC Sporting Group were all developed to assist hunters of feathered game. These “sporting dogs” (also referred to as gundogs or bird dogs) are subdivided by function—that is, how they hunt. They are spaniels, pointers, setters, retrievers, and the European utility breeds. Of these, spaniels are generally considered the oldest. Early authorities divided the spaniels not by breed but by type: either water spaniels or land spaniels. The land spaniels came to be subdivided by size. The larger types were the “springing spaniel” and the “field spaniel,” and the smaller, which specialized on flushing woodcock, was known as a “cocking spaniel.” ~~How many breeds are in this group? 31~~ 1. American Water Spaniel a. Country of origin: USA (lake country of the upper Midwest) b. Original purpose: retrieve from skiff or canoes and work ground c. Other Names: N/A d. Very Brief History: European immigrants who settled near the great lakes depended on the region’s plentiful waterfowl for sustenance. The Irish Water Spaniel, the Curly-Coated Retriever, and the now extinct English Water Spaniel have been mentioned in histories as possible component breeds. e. Coat color/type: solid liver, brown or dark chocolate. A little white on toes and chest is permissible. -

The Practice of Hunting As a Way to Transcend Alienation from Nature

The Journal of Transdisciplinary Environmental Studies vol. 17, no. 1, 2019 The Practice of Hunting as a Way to Transcend Alienation from Nature Lara Tickle, Ph.D. scholar Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) Division of Environmental Communication Department of Urban and Rural Development Postal address: P.O. Box 7012, SE-750 07 Uppsala, SWEDEN Visiting and delivery address: Ulls väg 28, SE-756 51 Uppsala, SWEDEN Telephone: +46 (0) 186 725 88 Abstract: This paper explores whether and to what extent the practice of leisure hunting is used as a way to transcend the human-nature alienation and thereby reconcile modern society and nature. The study is based on semi-structured interviews with hunters around Stockholm, Sweden and participant observation. In the paper, modernity is discussed from a Marxist perspective as causing the alienation of human beings from nature and natural sources of production through processes of industrialisation, capitalism and urbanisation. By exploring hunting as an ancient activity in a modern society the paper further discusses whether hunting can, through managing and harvesting wildlife, offer some kind of insight into people’s interaction with natural sources of production. The question is whether hunting has the potential to facilitate a more profound appreciation of wildlife and ecosystems by reconnecting people with nature. The effects of Modernity on hunting are also discussed to reflect some of the paradoxes and internal contradictions that exist within hunting. Keywords: Hunting, Alienation, Reconciliation, Modernity, Nature Introduction The first question that led to this project is “why monetize value and separate producers from con- would modern people want to hunt?”. -

Anthrozoology and Sharks, Looking at How Human-Shark Interactions Have Shaped Human Life Over Time

Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Affairs University of Washington 2020 Committee: Marc L. Miller, Chair Vincent F. Gallucci Program Authorized to Offer Degree School of Marine and Environmental Affairs © Copywrite 2020 Jessica O’Toole 2 University of Washington Abstract Anthrozoology and Public Perception: Humans and Great White Sharks (Carchardon carcharias) on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, USA Jessica O’Toole Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Marc L. Miller School of Marine and Environmental Affairs Anthrozoology is a relatively new field of study in the world of academia. This discipline, which includes researchers ranging from social studies to natural sciences, examines human-animal interactions. Understanding what affect these interactions have on a person’s perception of a species could be used to create better conservation strategies and policies. This thesis uses a mixed qualitative methodology to examine the public perception of great white sharks on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While the area has a history of shark interactions, a shark related death in 2018 forced many people to re-evaluate how they view sharks. Not only did people express both positive and negative perceptions of the animals but they also discussed how the attack caused them to change their behavior in and around the ocean. Residents also acknowledged that the sharks were not the only problem living in the ocean. They often blame seals for the shark attacks, while also claiming they are a threat to the fishing industry. -

My Sister Is Vegetarian, but I Hunt by Kayci M., Age 16

OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF SCI CHAPTERS IN WISCONSIN AND ILLINOIS JULY/AUGUST 2020 My Sister is Vegetarian, But I Hunt by Kayci M., age 16 • Education: R3 Youth Turkey • Humanitarian: COVID Time to Decide • Hunters’ Rights Updates • Chapter News & Events • Who is True Conservationist 18 ACRES...NOTHIN’ BUT ARCHERY Proud HUNTERSOfficial Magazine of SCI Chapters in Wisconsin and Illinois Supporter of: July/August 2020 Editor/Publishers: Mark & Coni LaBarbera On the cover: Kayci Martensen became a successful young hunter while her sister became a vegetarian. Kayci’s deer story starts on page 16. HUNTERS is a bimonthly publication for members of SCI chapters in Wisconsin, 5 Legislative Update plus bonus electronic circulation, which by Dan Trawicki, SCI Lobbyist includes some of the world’s most avid and affluent conservationists who enjoy 6 SCI Region 16 Report hunting here and around the world. They by Regional Rep. Charmaine Wargolet have earned a reputation of leadership on natural resources issues and giving to pro- 6 Safe for Sale tect and support the future of hunting and 7 Mom & Son Success conservation here and abroad. To share by Tiffany Bielenberg Kramer your message with them, send ads and editorial submissions to Mark LaBarbera at 8 Boar-dom Beats Covid Boredom [email protected]. by Mark LaBarbera Submission of story and photos means that 9 Illinois & Chicago Chapter Report you are giving SCI permission to use them 9 Nominate Trailblazer free in SCI printed or electronic form. 10 Badgerland Chapter Report Issue Deadline__ by President Randy Mayes January/February November 20 March/April January 20 10 Legislative: Canadian Gun Ban May/June March 20 10 Small, LaBarbera Win Awards July/August May 20 September/October July 20 11 Wisconsin Chapter Report THE MIDWEST’S PREMIER ARCHERY FACILITY November/December September 20 by President Fred Spiewak New Advertisers 12 Northeast Wisconsin Chapter Report The number of advertisers allowed in WI by President Marty Witczak SCI HUNTERS magazine is limited. -

Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY

Military Working Dog History Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY NOLAN A. WATSON, MLA* INTRODUCTION COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR WORLD WAR I WORLD WAR II KOREAN WAR AND THE EARLY COLD WAR VIETNAM WAR THE MILITARY WORKING DOG CONCLUSION *Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Regimental Historian; AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Medical Command, 2748 Worth Road, Suite 28, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Branch Historian, Military Police Corps, US Army Military Police School, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri 83 Military Veterinary Services INTRODUCTION History books recount stories of dogs accompany- which grew and changed with subsequent US wars. ing ancient armies, serving as sources of companion- Currently, US forces utilize military working dogs ship and performing valuable sentry duties. Dogs also (MWDs) in a variety of professions such as security, fought in battle alongside their owners. Over time, law enforcement, combat tracking, and detection (ie, however, the role of canines as war dogs diminished, for explosives and narcotics). Considered an essential especially after firearms became part of commanders’ team member, an MWD was even included in the arsenals. By the 1800s and up until the early 1900s, the successful raid against Osama Bin Laden in 2011.1 (See horse rose to prominence as the most important mili- also Chapter 3, Military Working Dog Procurement, tary animal; at this time, barring some guard duties, Veterinary Care, and Behavioral Services for more dogs were relegated mostly to the role of mascots. It information about the historic transformation of the was not until World War II that the US Army adopted MWD program and the military services available broader roles for its canine service members—uses for canines.) COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR Early American Army dogs were privately owned tary continued throughout the next century and into at first; there was neither a procurement system to the American Civil War. -

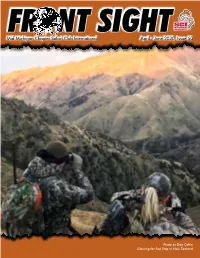

June 2020, Issue 50

FRONT SIGHT MID-MICHIGAN CHAPTER Mid-Michigan Chapter Safari Club International April - June 2020, Issue 50 Photo by Dan Catlin Glassing for Red Stag in New Zealand SAFARIS SOUTH AFRICA ZIMBABWE MOZAMBIQUE WWW. JP SAFARIS.CO.ZA [email protected] FR NT SIGHT In This Issue - April - June 2020 Standing Committees Chairmen are listed first 2 Chapter Officers and Board Members 3 President’s Message Chapter Record Book - Mary Browning 3 Editor’s Message Conservation/Govt. Affairs - Mary Browning 3 Meeting and Events Schedule Dispute Resolution - Abbe Mulders, Kevin Unger, Jon Zieman 4 Book Review — by Josh Christensen Matching Grants - Jon Zieman Journal of a Trapper — by Osborne Russell 5 Trophy Awards Program Front Sight Publication/Advertising - Mary Harter, Don Catlin 6 - 7 Big Buck Night 2020 Education - Doug Chapin 8 - 9 2020 National Convention - Reno, NV Membership - Abbe Mulders 10 National Convention Award - Larry Higgins Nominating - Kevin Unger, Jon Zieman, 11 80 Yr Old Arrows Buck - by Robert C. Mills Abbe Mulders, Janis Ransom 12 - 13 Bird Hunting at Meemo’s - by Mary Harter Programs for Membership Meetings - Doug Chapin 14 - 15 Hunting in New Zealand - by Dan Catlin Big Buck Night - Mike Strope, Kevin Unger, Scott Holmes 16 - 19 Goats at 55? - by Bob Blazer 20 - 21 Last Minute Trophy - by Roger Card Annual Awards Banquet/Fundraiser - Abbe and Joe Mulders, Kevin Unger, and all board members 22 - 23 Thank You for Sponsorship at AWLS - by Katrina Spry & Sarah Westervelt Outfitter Donations - Roger Froling, Mike Strope, Scott Holmes, Kevin Unger, Joe Mulders 24 - 25 Grand Slam - by Tim Torpey 26 - 32 Advertisers Raffles - Doug Chapin Public Relations and Marketing - Kevin Chamberlain Shooting Sports - Tim Schafer Humanitarian Services - Mike Strope Sportsman Against Hunger - Mike Strope Pathfinder Hunts - Brandon Jurries Youth - Disabled Veterans - Blue Bags, etc. -

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry CIV-2010-485 in the Matter of Judicature Amendment Act 1972 and New Zealand

In the High Court of New Zealand Auckland Registry CIV-2010-485 In the matter of Judicature Amendment Act 1972 AND New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 AND Animal Welfare (Commercial Slaughter) Code of Welfare 2010 AND Animal Welfare (Commercial Slaughter) Code of Welfare 2002 BETWEEN AUCKLAND HEBREW CONGREGATION TRUST BOARD – a Charitable trust incorporated on 17 January 1955 under Part II of the Religious Charitable and Educational Trusts Act 1908 now known as the Charitable Trusts Act 1957 First plaintiff AND THE WELLINGTON JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTRE – a Charitable Trust incorporated on 4 March 1986 under the Charitable Trusts Act 1957 Second plaintiff AND MINISTER OF AGRICULTURE Defendant Submissions of proposed intervenor The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty in support of plaintiffs Dated: 24 November 2010 2 MAY IT PLEASE THE COURT: INTRODUCTION Interest of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty 1. The Becket Fund for Religious Liberty is a non-profit, nongovernmental, international law firm dedicated to protecting the practice of all religious traditions. It has represented agnostics, Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, Native Americans, Santeros, Sikhs, and Zoroastrians, among others, in lawsuits around the world. It is frequently involved, both as counsel of record, and as amicus curiae , in cases seeking to preserve universal religious liberty: the freedom of all religious people to pursue their beliefs without undue government interference. 2. The Becket Fund has represented a wide variety of groups whose religious convictions have come into conflict with government regulation. In France, the Becket Fund advised Sikh students in their case before the Conseil d’État and the European Court of Human Rights.