Thestateofhousinginek Urhuleni: Urbaninfilling Vs Megaprojectsin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gauteng No Fee Schools 2021

GAUTENG NO FEE SCHOOLS 2021 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2021 NUMBERS NUMBER 2021 700910011 ADAM MASEBE SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY 110, BLOCK A, SEKAMPANENG, TEMBA, TEMBA, 0407 TSHWANE NORTH 1 1056 700400393 ALBERTINA SISULU PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1250, SIBUSISO, KINGSWAY, BENONI, BENONI, 1501 EKURHULENI NORTH 1 1327 24936, CNR ALEKHINE & STANTON RD, PROTEA SOUTH, 700121210 ALTMONT TECHNICAL HIGH SCHOOL SECONDARY JOHANNESBURG CENTRAL 1 1395 SOWETO, JOHANNESBURG, 1818 2544, MANDELA & TAMBO, BLUEGUMVIEW, DUDUZA, NIGEL, 700350561 ASSER MALOKA SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1623 1496 2201, MAMASIYANOKA, GA-RANKUWA VIEW, GA-RANKUWA, 700915064 BACHANA MOKWENA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE WEST 1 993 PRETORIA, 0208 22640, NGUNGUNYANE AVENUE, BARCELONA, ETWATWA, 700400277 BARCELONA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY GAUTENG EAST 1 1809 BENONI, 1519 577, KAALPLAATS, BARRAGE, VANDERBIJLPARK, 700320291 BARRAGE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 317 JOHANNESBURG, 1900 11653, LINDANI STREET, OLIEVENHOUTBOSCH, CENTURION, 700231522 BATHABILE PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1541 PRETORIA, 0175 700231530 BATHOKWA PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 1, LEPHORA STREET, SAULSVILLE, PRETORIA, PRETORIA, 0125 TSHWANE SOUTH 1 1081 25, OLD PRETORIA ROAD BAPSFONTEIN, BAPSFONTEIN, 700211276 BEKEKAYO PRIMARY FARM SCHOOL PRIMARY EKURHULENI NORTH 1 139 BENONI, BENONI, 1510 2854, FLORIDA STREET, BEVERLY HILLS, EVATON WEST, 700320937 BEVERLY HILLS SECONDARY SCHOOL SECONDARY SEDIBENG WEST 1 1504 -

Boksburg Quality Used Sparesopel, Chev and Isuzu

BOKSBURG QUALITY USED SPARESOPEL, CHEV AND ISUZU Advertiser Tel: 011 894-1322 / 011 894-5987 Fax: 086 557-1717 Email: [email protected] www.lopec.co.za www.boksburgadvertiser.co.za Unit 14, Middle Offi ce Park, Top Road, Anderbolt, Boksburg Friday,Friday, FebruaryFeb 2, 2018, • 20 Sydney Road, Ravenswood Tel: 011 916-5385, Fax: 011 918-6311 • www.boksburgadvertiser.co.za • FREE • Crowning COMMUNITY NEWS COUNCIL NEWS SPORT glory for local student Arts need saving Mapleton takes metro Boksburg Cricket teacher 10 from pigeon poop 3 to task over power 6 Club takes charge 20 UBER CASE FUELS OUTRAGE Lana O’ Neill [email protected] The case in which a Sunward Park man is accused of brutally stabbing a female Uber driver and trying to drive over her with her own car on December 26 last year, drew a large crowd comprising members of the media and supporters of an advocacy group, to the Boksburg Magistrate’s Court on January 24. The accused, Jacques Henry Scharneck (29), was on parole for a rape conviction at the time of the attack. He was arrested for the attack on December 27, last year, and at his fi rst appearance in the Boksburg District Court, bail was denied and he was remanded in custody. Wednesday, last week, was his fi rst appearance in the Boksburg Region- al Court and saw him shuffl e into the courtroom in leg irons, wearing jeans and a khaki jacket. The case was postponed to Febru- ary 27 for further investigation and Scharneck was remanded in custody. -

South Africa's Xenophobic Eruption

South Africa’s Xenophobic Eruption INTRODUCTION We also visited two informal settlements in Ekhuruleni: Jerusalem and Ramaphosa. In Ramaphosa, Between 11 and 26 May 2008, 62 people, the major- the violence was sustained and severe. At time of writing, ity of them foreign nationals, were killed by mobs in four months to the day aft er the start of the riots, not a Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and elsewhere. Some single foreign national has returned.2 In Jerusalem, in 35,000 were driven from their homes.1 An untold number contrast, the violence, although severe, lasted a single of shacks were burnt to the ground. Th e troubles were night, before it was quelled by police and residents. Our dubbed South Africa’s ‘xenophobic riots’. Th ey constitute visits to these sites were particularly fruitful inasmuch as the fi rst sustained, nationwide eruption of social unrest we were able to conduct six reasonably intensive inter- since the beginning of South Africa’s democratic era views with young men who claimed to have joined the in 1994. mobs and participated in the violence. Between 1 and 10 June, in the immediate aft ermath Th e fi rst section of this paper recounts at some length of the riots, I, together with the photojournalist Brent the experience of a single victim of the xenophobic vio- Stirton, visited several sites of violence in the greater lence in South Africa, a Mozambican national by the name Johannesburg area. In all we interviewed about 110 of Benny Sithole. Th e second section explores the genesis people. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON

THE PROVINCE OF DIE PROVINSIE VAN UNITY DIVERSITY GAUTENG IN GAUTENG Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant EXTRAORDINARY • BUITENGEWOON Selling price • Verkoopprys: R2.50 Other countries • Buitelands: R3.25 PRETORIA Vol. 25 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. 289 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 We oil Irawm he power to pment kiIDc AIDS HElPl1NE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure ISSN 1682-4525 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 00289 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 452005 2 No. 289 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 IMPORTANT NOTICE OF OFFICE RELOCATION GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS PUBLICATIONS SECTION Dear valued customer, We would like to inform you that with effect from the 1st of November 2019, the Publications Section will be relocating to a new facility at the corner of Sophie de Bruyn and Visagie Street, Pretoria. The main telephone and facsimile numbers as well as the e-mail address for the Publications Section will remain unchanged. Our New Address: 88 Visagie Street Pretoria 0001 Should you encounter any difficulties in contacting us via our landlines during the relocation period, please contact: Ms Maureen Toka Assistant Director: Publications Cell: 082 859 4910 Tel: 012 748-6066 We look forward to continue serving you at our new address, see map below for our new location. C1ty Of Tshwané J Municipal e , I I r e ;- e N 4- 4- Loreto Convent _-Y School, Pretoria ITShwane L e UMttersi Techrtolog7 Government Printing Works Publications _PAl11TGl l LMintys Tyres Pretori solest Star 88 Visagie Street Q II _ 4- Visagie St Visagie St 9 Visagie St F e Visagie St Visal Government Printing Works Waxing National Museum of Cultural- Malas Drive Style Centre Tshwane á> 9 The old Fire Station, PretoriaCentralo Minnaar St Minnaar St o Minnaar p 91= tarracks This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za PROVINSIALE KOERANT, BUITENGEWOON, 18 SEPTEMBER 2019 No. -

Profile: City of Ekurhuleni

2 PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI PROFILE: CITY OF EKURHULENI 3 CONTENT 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction: Brief Overview............................................................................. 6 2.1 Historical Perspective ............................................................................................... 6 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Spatial Integration ................................................................................................. 8 3. Social Development Profile............................................................................... 9 3.1 Key Social Demographics ........................................................................................ 9 3.2 Health Profile .......................................................................................................... 12 3.3 COVID-19 .............................................................................................................. 13 3.4 Poverty Dimensions ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Distribution .......................................................................................................... 15 3.4.2 Inequality ............................................................................................................. 16 3.4.3 Employment/Unemployment -

City of Ekurhuleni Clinic Rooster and Contact Numbers 2018

Enquiries: Dr. K. Motshwane Tel no: +27 11 876 1717 Fax no: +27 11 825- 2219 E-Mail: [email protected] City of Ekurhuleni Clinic Rooster and Contact Numbers 2018 Clinic Contact for bookings Contact Number Psychologist Clinic Day for Visit (011) 422 -5765 / (011) 421 - Mary Moodley Clinic Sr. Mahlangu / Sr Brenda Ms. Singqobile Gumede Mondays 8680/ 076 868 6041 Phillip Moyo Clinic Psych Sr (011) 426 - 4974 Ms. Singqobile Gumede Tuesdays Daveyton Clinic Psych Sr / Zinzi (clerk (011) 999 - 6947 Ms. Singqobile Gumede Wednesdays Northmead Clinic Sr. Salmah (011) 425 - 2430 Ms. Singqobile Gumede Thursdays Nokuthela CHC, Dunnottar Sr. Nomthandazo Gama (011) 737 – 9743/061 010 1455 Mr. Mojalefa Makgata Thursdays & Fridays Kwa-Thema CHC Sr. Lenong / Sr. Pinky (011) 736 - 3106 Mr. Mojalefa Makgata Tuesdays Tsakane Main Clinic Sr. Mokone (011) 999 - 8008 Mr. Mojalefa Makgata Wednesdays Sonto Thobela, Duduza Reception (011) 999 - 9092 Mr. Mojalefa Makgata 2nd and 4th Mondays Ext. 10 Clinic Tsakane Reception (011) 999 - 1123 Mr. Mojalefa Makgata 1st and 3rd Mondays Nokuthela CHC Mr. Werner Wichmann (011) 737 - 9740/083 303 0041 Mr. Werner Wichmann Tuesdays/Wednesdays/Fridays Springs Clinic Psych Nurse (011) 999 9048 /-8792 /-7701 Mr. Werner Wichmann Thursdays Nigel Clinic Psych Nurse (Patricia) (011) 999- 9324 / -9242 Mr. Werner Wichmann 2nd & 4th Monday Duduza Main Clinic Psych Nurse (Emma) (011) 999- 9099 / -9098 / -9100 Mr. Werner Wichmann 1st & 3rd Monday Brakpan Clinic Sr Enid (011) 999 - 7937 Ms. Mavis Dhlamini Tuesday Van Dyk Park No allocated Sr. for MH (011) 999 – 5958/073 095 2315 Ms. Mavis Dhlamini Wednesday- Vosloorus Poly Clinic Sr Moipone (011) 906 - 1166 Ms. -

Gauteng Gauteng Brakpan Sheriff Service Area Brakpan Sheriff

# # !C # # # # # ^ !C # !. ñ!C# # # # !C # $ # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # ñ # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # ^ # # !C # !C # # # # # # # # $ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # ## # # # # !C # # # # # !C# # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ñ # !C # # # # # # !C # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # !C # # !C # # # # # # !C # # # !C # ## !C !. # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # ## # # # # # # # # ñ # # # ^ # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # !C !C# ## # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C # # # $ # # !C # # !C # # # # !C # # # ^ # # # ^ ## !C # # # !C # #!C # # # # # ñ # # # # # ## # # # !C## # # # # # # # -

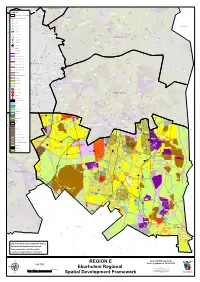

REGION E Ekurhuleni Regional Spatial Development Framework

D R T N ASTON MANOR E TR M NIMROD PARK S J K A U W V O R K N R E G I O N B L A 6 1 R E G I O N B N IL R 8 P O R W A I 2 W M EB H E 1 V EC E BREDELL AH R 3 K IG K D R H 6 D T 8 W R GLEN MARAIS H A T A S KEMPTON PARK V T E T T KEMPTON PARK AH L B D E IR N C A R H R D D R Legend U BENONI AH D P POMONA ESTATES AH D E GORDONS VIEW AH R E ETWATWA K N 8 N 1 O 6 Z T K C 5 S O R O D T N 5 Urban Managment Regional Boundaries N R R S N L T Y VO ON A E OR G L R TR STR N TR ESTHERPARK E G O S KKE T D R I G L ST A O LILYVALE AH R IG S N AR R2 T E M AL AVE 1 R QU ENTR EE L C NSB RD UR G Urban Development Boundary Y R RN S 0 D CO M K 9 A A 6 L K 8 M L 3 D 2 AS R S HOM T T NORTONS HOME ESTATES AH ï R K6 ILE RD G 8 CEC S E P L BRESWOL AH 5 Airport O D o 8 K 1 R K E D N I 6 1 D T BENONI ORCHARDS AH R V 1 1 H A K S H N R K R V 9 T O E 6 U R A E R S H W D D 9 Y V T Y H L E E G G S V BENONI SMALL FARMS S I P POMONA L R S N I S I H S S N A K T O R JATNIEL T T S R E S W N SLATERVILLE AH R H T Cemetery A C R S SPARTAN ïR H D T Y R T T I K BENONI NORTH AH K VALKHOOGTE SHANGRI-LA AH 1 OX RD ENN RD 0 L PITTS v® HoRsHpODitEaSFlIELD 9 FAIRLEAD AH INGLETHORPE AH PUTFONTEIN AH D E L M A S K RD D 1 D R G BONAEROPARK SA I R 0 A L U I S O P B A L E 5 R I R D R R D K O R D O MAYFIELD T R I N N S I R T T W I A 1 N N N E G ï E S T E N L 5 E O S Landfill SiOte 5 D T R 6 E L S ? N 7 R S P R S I R R 8 E L 5 E D R T O I W T A S R K S 1 S N V T 7 E N L O R K L A 3 1 N E D T 3 R E V N A V 7 ISANDO B H 1 C E K A CARO NOME AH W R NDR d M E G Logistics Hub REYV P E ENSTEY E LEK N -

Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality Urban Settlements Development Grant

EKURHULENI METROPOLITAN MUNICIPALITY URBAN SETTLEMENTS DEVELOPMENT GRANT Presentation to Human Settlements Portfolio Committee – 12 Sept 2012 Content 1. Strategic Overview of delivery environment – Key demographic and socio-economic statistics – Services Backlog – Spatial Analysis – Priorities in relation to creation of sustainable Human Settlements 2. BEPP – Budget – Performance Indicators – Risks and challenges 3. USDG Business Plan 2012/13 – Targets & delivery/performance/expenditure 4. Outcome 8 Related Projects: USDG Planning & Delivery 5. Grants Alignment 2 Demographics, social and economic content Key Statistics (2010 estimates) Ekurhuleni Geographic size of the region (sq km) 1928 Population 2,873,997 Population density (number of people per sq km) 1490.72 Economically active population (as % of total population) 48.6 Number of households 909,886 Annual per household income (Rand, current prices) 151,687 Annual per capita income (Rand, current prices) 49,482 Gini coefficient 0.62 Formal sector employment estimates 759,252 3 Demographics, social and economic content Key Statistics (2010 estimates) Ekurhuleni Informal sector employment estimates 93,013 Unemployment rate (expanded definition) 31.1 Percentage of people in poverty 27.5 Poverty gap (R millions) 1,653 Human development index (HDI) 0.65 Index of Buying Power (IBP) 0.08 Total economic output in 2010 (R million at current prices) 137,980 Share of economic output (GVA % of SA in current prices) 6.5 Total economic output in 2010 (R millions at constant 2005 prices) 67,211,143 -

For More Information, Contact the Office of the Hod: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction

The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. Towns that make up the City of Ekurhuleni are Greater Alberton, Benoni, Germiston, Duduza, Daveyton, Nigel, Springs, KwaThema, Katlehong, Etwatwa, Kempton Park, Edenvale, Brakpan, Vosloorun, Tembisa, Tsakane, and Boksburg. Ekurhuleni region accounts for a quarter of Gauteng’s economy and includes sectors such as manufacturing, mining, light and heavy industry and a range of others businesses. Covering such a large and disparate area, transport is of paramount importance within Ekurhuleni, in order to connect residents to the business areas as well as the rest of Gauteng and the country as a whole. Ekurhuleni is highly regarded as one of the main transport hubs in South Africa as it is home to OR Tambo International Airport; South Africa’s largest railway hub and the Municipality is supported by an extensive network of freeways and highways. In it features parts of the Maputo Corridor Development and direct rail, road and air links which connect Ekurhuleni to Durban; Cape Town and the rest of South Africa. There are also linkages to the City Deep Container terminal; the Gautrain and the OR Tambo International Airport Industrial Development Zone (IDZ). For more information, contact the Office of the HoD: • 011 999 3845/6194 Introduction The City of Ekurhuleni covers an extensive area in the eastern region of Gauteng. This extensive area is home to approximately 3.1 million and is a busy hub that features the OR Tambo International Airport, supported by thriving business and industrial activities. -

Proposed Township Development: Vosloorus Extension 24

PROPOSED TOWNSHIP DEVELOPMENT: VOSLOORUS EXTENSION 24, VOSLOORUS EXTENSION 41 AND VOSLOORUS EXTENSION 43. Heritage Impact Assessment for the proposed development of Vosloorus Extension 24, Vosloorus Extension 41 and Vosloorus Extension 43 on Portion 144 of the farm Vlakplaats 138 IR, Boksburg Local Muncipality, Ekurhuleni District Municipality, Gauteng Province. Issue Date: 12 August 2014 Revision No.: 2 Client: Enkanyini Projects DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE The report has been compiled by PGS Heritage, an appointed Heritage Specialist for Enkanyini Projects. The views stipulated in this report are purely objective and no other interests are displayed in the findings and recommendations of this Heritage Impact Assessment. HERITAGE CONSULTANT: PGS Heritage CONTACT PERSON: Polke Birkholtz Tel: +27 (012) 332 5305 Fax: +27 (012) 332 2625 Email: [email protected] SIGNATURE: ______________________________ CLIENT: Enkanyini Projects CONTACT PERSON: Matilda Azong Tel: 012 657 1505 Fax: 012 657 0220 email: [email protected] HIA –Kwazenzele Housing Project Page ii of vi Report Title Heritage Impact Assessment For The Proposed New Township: Vosloorus Extension 24, Vosloorus Extension 41 and Vosloorus Extension 43, Situated On Part Portion 144 Of The Farm Vlakplaats 138-IR, Boksburg Local Muncipality, Ekurhuleni District Municipality, Gauteng Province. Control Name Signature Designation Authors Polke Birkholtz Heritage Specialist / PGS Heritage Client Matilda Azong Client / Enkanyini Projects HIA – VOSLOORUS EXT. 24, VOSLOORUS