Algaas Anode Heterojunction PIN Diodes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federico Capasso “Physics by Design: Engineering Our Way out of the Thz Gap” Peter H

6 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON TERAHERTZ SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, VOL. 3, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 Terahertz Pioneer: Federico Capasso “Physics by Design: Engineering Our Way Out of the THz Gap” Peter H. Siegel, Fellow, IEEE EDERICO CAPASSO1credits his father, an economist F and business man, for nourishing his early interest in science, and his mother for making sure he stuck it out, despite some tough moments. However, he confesses his real attraction to science came from a well read children’s book—Our Friend the Atom [1], which he received at the age of 7, and recalls fondly to this day. I read it myself, but it did not do me nearly as much good as it seems to have done for Federico! Capasso grew up in Rome, Italy, and appropriately studied Latin and Greek in his pre-university days. He recalls that his father wisely insisted that he and his sister become fluent in English at an early age, noting that this would be a more im- portant opportunity builder in later years. In the 1950s and early 1960s, Capasso remembers that for his family of friends at least, physics was the king of sciences in Italy. There was a strong push into nuclear energy, and Italy had a revered first son in En- rico Fermi. When Capasso enrolled at University of Rome in FREDERICO CAPASSO 1969, it was with the intent of becoming a nuclear physicist. The first two years were extremely difficult. University of exams, lack of grade inflation and rigorous course load, had Rome had very high standards—there were at least three faculty Capasso rethinking his career choice after two years. -

DESIGN and FABRICATION of Gan-BASED HETEROJUNCTION BIPOLAR TRANSISTORS

DESIGN AND FABRICATION OF GaN-BASED HETEROJUNCTION BIPOLAR TRANSISTORS By KYU-PIL LEE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2003 In his heart a man plans his course, But, the LORD determines his steps. Proverbs 16:9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to express great appreciation with all my heart to Professor Pearton and Professor Ren for their expert advice, guidance, and instruction throughout the research. I also give special thanks to members of my committee (Professor Abernathy, Professor Norton, and Professor Singh) for their professional input and support. Additional special thanks are reserved for the people of our research group (Kwang-hyun, Kelly, Ben, Jihyun, and Risarbh) for their assistance, care, and friendship. I am very grateful to past group members (Sirichai, Pil-yeon, David, Donald and Bee). 1 also give my thanks to P. Mathis for her endless help and kindness; and to Mr. Santiago who is network assistant in the Chemical Engineering Department, because of his great help with my simulation. I also thank my discussion partners about material growth technologies, Dr. B. Gila, Dr. M. Overberg, Jerry and Dr. Kang-Nyung Lee. I would like to give my thanks to my friends (especially Kyung-hoon, Young-woo, Se-jin, Byeng-sung, Yong-wook, and Hyeng-jin). Even when they were very busy, they always helped my research work without hesitation. I cannot forget Samsung's vice president Dr. Jong-woo Park’s devoted help, and the steadfast support from Samsung Electronics. -

Based Vertical Double Heterojunction Bipolar Transistors with High Current Amplification

COMMUNICATION Heterojunction Bipolar Transistor www.advelectronicmat.de 2D Material-Based Vertical Double Heterojunction Bipolar Transistors with High Current Amplification Geonyeop Lee, Stephen J. Pearton, Fan Ren, and Jihyun Kim* been applied to various types of semicon- The heterojunction bipolar transistor (HBT) differs from the classical homo- ductor devices, such as lasers, solar cells, junction bipolar junction transistor in that each emitter-base-collector layer high electron mobility transistors, and het- [3–6] is composed of a different semiconductor material. 2D material (2DM)- erojunction bipolar transistors (HBTs). Notably, with a bipolar junction transistor, based heterojunctions have attracted attention because of their wide range which is a three-terminal transistor fabri- of fundamental physical and electrical properties. Moreover, strain-free cated by connecting two P–N homojunc- heterostructures formed by van der Waals interaction allows true bandgap tion diodes, there is a trade-off between engineering regardless of the lattice constant mismatch. These characteristics the current gain and high-frequency ability [3,7] make it possible to fabricate high-performance heterojunction devices such because of these problems. In sharp contrast, HBTs realized using the hetero- as HBTs, which have been difficult to implement in conventional epitaxy. structure can avoid these trade-offs and Herein, NPN double HBTs (DHBTs) are constructed from vertically stacked improve device performance.[8] HBTs, due 2DMs (n-MoS2/p-WSe2/n-MoS2) using dry transfer technique. The forma- to their high power efficiency, uniformity tion of the two P–N junctions, base-emitter, and base-collector junctions, of threshold voltage, and low 1/f noise in DHBTs, was experimentally observed. -

Quantum Dot and Electron Acceptor Nano-Heterojunction For

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Quantum dot and electron acceptor nano‑heterojunction for photo‑induced capacitive charge‑transfer Onuralp Karatum1, Guncem Ozgun Eren2, Rustamzhon Melikov1, Asim Onal3, Cleva W. Ow‑Yang4,5, Mehmet Sahin6 & Sedat Nizamoglu1,2,3* Capacitive charge transfer at the electrode/electrolyte interface is a biocompatible mechanism for the stimulation of neurons. Although quantum dots showed their potential for photostimulation device architectures, dominant photoelectrochemical charge transfer combined with heavy‑metal content in such architectures hinders their safe use. In this study, we demonstrate heavy‑metal‑free quantum dot‑based nano‑heterojunction devices that generate capacitive photoresponse. For that, we formed a novel form of nano‑heterojunctions using type‑II InP/ZnO/ZnS core/shell/shell quantum dot as the donor and a fullerene derivative of PCBM as the electron acceptor. The reduced electron–hole wavefunction overlap of 0.52 due to type‑II band alignment of the quantum dot and the passivation of the trap states indicated by the high photoluminescence quantum yield of 70% led to the domination of photoinduced capacitive charge transfer at an optimum donor–acceptor ratio. This study paves the way toward safe and efcient nanoengineered quantum dot‑based next‑generation photostimulation devices. Neural interfaces that can supply electrical current to the cells and tissues play a central role in the understanding of the nervous system. Proper design and engineering of such biointerfaces enables the extracellular modulation of the neural activity, which leads to possible treatments of neurological diseases like retinal degeneration, hearing loss, diabetes, Parkinson and Alzheimer1–3. Light-activated interfaces provide a wireless and non-genetic way to modulate neurons with high spatiotemporal resolution, which make them a promising alternative to wired and surgically more invasive electrical stimulation electrodes4,5. -

17 Band Diagrams of Heterostructures

Herbert Kroemer (1928) 17 Band diagrams of heterostructures 17.1 Band diagram lineups In a semiconductor heterostructure, two different semiconductors are brought into physical contact. In practice, different semiconductors are “brought into contact” by epitaxially growing one semiconductor on top of another semiconductor. To date, the fabrication of heterostructures by epitaxial growth is the cleanest and most reproducible method available. The properties of such heterostructures are of critical importance for many heterostructure devices including field- effect transistors, bipolar transistors, light-emitting diodes and lasers. Before discussing the lineups of conduction and valence bands at semiconductor interfaces in detail, we classify heterostructures according to the alignment of the bands of the two semiconductors. Three different alignments of the conduction and valence bands and of the forbidden gap are shown in Fig. 17.1. Figure 17.1(a) shows the most common alignment which will be referred to as the straddled alignment or “Type I” alignment. The most widely studied heterostructure, that is the GaAs / AlxGa1– xAs heterostructure, exhibits this straddled band alignment (see, for example, Casey and Panish, 1978; Sharma and Purohit, 1974; Milnes and Feucht, 1972). Figure 17.1(b) shows the staggered lineup. In this alignment, the steps in the valence and conduction band go in the same direction. The staggered band alignment occurs for a wide composition range in the GaxIn1–xAs / GaAsySb1–y material system (Chang and Esaki, 1980). The most extreme band alignment is the broken gap alignment shown in Fig. 17.1(c). This alignment occurs in the InAs / GaSb material system (Sakaki et al., 1977). -

Heterojunction Quantum Dot Solar Cells

Heterojunction Quantum Dot Solar Cells by Navid Mohammad Sadeghi Jahed A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical and Computer Engineering Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Navid Mohammad Sadeghi Jahed 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract The advent of new materials and application of nanotechnology has opened an alternative avenue for fabrication of advanced solar cell devices. Before application of nanotechnology can become a reality in the photovoltaic industry, a number of advances must be accomplished in terms of reducing material and process cost. This thesis explores the development and fabrication of new materials and processes, and employs them in the fabrication of heterojunction quantum dot (QD) solar cells in a cost effective approach. In this research work, an air stable, highly conductive (ρ = 2.94 × 10-4 Ω.cm) and transparent (≥85% in visible range) aluminum doped zinc oxide (AZO) thin film was developed using radio frequency (RF) sputtering technique at low deposition temperature of 250 °C. The developed AZO film possesses one of the lowest reported resistivity AZO films using this technique. The effect of deposition parameters on electrical, optical and structural properties of the film was investigated. Wide band gap semiconductor zinc oxide (ZnO) films were also developed using the same technique to be used as photo electrode in the device structure. -

Band Alignment and Graded Heterostructures

Band Alignment and Graded Heterostructures Guofu Niu Auburn University Outline • Concept of electron affinity • Types of heterojunction band alignment • Band alignment in strained SiGe/Si • Cusps and Notches at heterojunction • Graded bandgap • Impact of doping on equilibrium band diagram in graded heterostructures Reference • My own SiGe book – more on npn SiGe HBT base grading • The proc. Of the IEEE review paper by Nobel physics winner Herb Kromer – part of this lecture material came from that paper • The book chapter of Prof. Schubert of RPI – book can be downloaded online from docstoc.com • http://edu.ioffe.ru/register/?doc=pti80en/alfer_e n.tex - by Alfreov, who shared the noble physics prize with Kroemer for heterostructure laser work 3 Band alignment • So far I have intentionally avoided the issue of band alignment at heterojunction interface • We have simply focused on – ni^2 change due to bandgap change for abrupt junction – Ec or Ev gradient produced by Ge grading • We have seen in our Sdevice simulation that the final band diagrams actually depend on doping – A Ec gradient favorable for electron transport is obtained for forward Ge grading in p-type (npn HBT) – A Ev gradient favorable for hole transport is obtained for forward Ge grading in n-type (pnp HBT) Electron Affinity – rough picture • Neglect interface between vacuum and semiconductor, vacuum level is drawn to be position independent • The energy needed to move an electron from Ec to vacuum level is called electron affinity. 5 Electron Affinity Model • The electron affinity model is the oldest model invoked to calculate the band offsets in semiconductor heterostructures (Anderson, 1962). -

Heterojunction Engineering for Next Generation Hybrid II-VI Materials

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Heterojunction Engineering for Next Generation Hybrid II-VI Materials Thor Garcia The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2385 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] HETEROJUNCTION ENGINEERING FOR NEXT GENERATION HYBRID II-VI MATERIALS by THOR AXTMANN GARCIA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in chemistry in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 THOR AXTMANN GARCIA All Rights Reserved ii Heterojunction Engineering for Next Generation Hybrid II-VI Materials by Thor Axtmann Garcia This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in chemistry in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Professor Maria C. Tamargo Chair of Examining Committee Date Professor Brian R. Gibney Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Professor Aidong Shen Professor Igor L. Kuskovsky Professor Glen Kowach THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Heterojunction Engineering for Next Generation Hybrid II-VI Materials by Thor Axtmann Garcia Advisor: Professor Maria C. Tamargo Molecular Beam Epitaxy(MBE) is a versatile thin film growth technique with monolayer control of crystallization. The flexibility and precision afforded by the technique allows for unique control of interfaces and electronic structure of the films grown. -

Microwave Characterization and Modeling of Gaas/Algaas Heterojunction Bipolar Transistors

b NASA Technical Metnorandurn 1001 50 Microwave Characterization and Modeling of GaAs/AlGaAs Heterojunction Bipolar Transistors { h AS A-'IN- 100 150) PIIC EC WAVE C HP ii ACTEHIZATICN NE 7-26 265 AEL: BCDELXNG CP GaAs/l!lGaAs kE?EfiCJUNC?ICti EIECZAS IEANSlS'lCLS (RASA) 34 F Avail: b31S EC A03/r,F AC1 CSCL 20N Unclas 63/32 OGi379C1 Rainee N. Simons and Robert R. Romanofsky Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio Prepared for the 'EEsof User's Group Meeting Las Vegas, Nevada, June 9, 1987 MICROWAVE CHARACTERIZATION AND MODELING OF GaAs/AlGaAs HETLROJUNCTION BIPOLAR TRANSISTORS Rainee N. Simons and Robert R. Romanofsky National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lewis Research Center Cleveland, Ohio 441 35 SUMMARY The characterization and modeling of a microwave GaAs/AlGaAs heterojunc- tion Bipolar Transistor (HBT) are discussed. The de-embedded scattering param- eters are used to derive a small signal lumped element equivalent circuit model using EEsof's "Touchstone" software package. Each element in the equivalent m 01 circuit model Is shown to have Its origin within the device. The model shows Ln m good agreement between the measured and modeled scattering parameters over a I wide range of bias currents. Further, the MAG and Ih211 calculated from w the measured data and the MAG and Ih211 predicted by the model are also in good agreement. Consequently the model should also be capable of predicting the fmax and fT of other HBTs. INTRODUCI ION In conventional GaAs Metal Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor (MESFET) and GaAs/AlGaAs High Electron Mobility Transistor (HEMT) devices, current con- duction is parallel to the surface and hence the device speed tends to be con- strained by limitations of the lithography process which defines the channel length. -

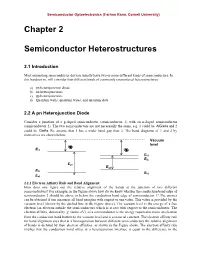

Chapter 2 Semiconductor Heterostructures

Semiconductor Optoelectronics (Farhan Rana, Cornell University) Chapter 2 Semiconductor Heterostructures 2.1 Introduction Most interesting semiconductor devices usually have two or more different kinds of semiconductors. In this handout we will consider four different kinds of commonly encountered heterostructures: a) pn heterojunction diode b) nn heterojunctions c) pp heterojunctions d) Quantum wells, quantum wires, and quantum dots 2.2 A pn Heterojunction Diode Consider a junction of a p-doped semiconductor (semiconductor 1) with an n-doped semiconductor (semiconductor 2). The two semiconductors are not necessarily the same, e.g. 1 could be AlGaAs and 2 could be GaAs. We assume that 1 has a wider band gap than 2. The band diagrams of 1 and 2 by themselves are shown below. Vacuum level q1 Ec1 q2 Ec2 Ef2 Eg1 Eg2 Ef1 Ev2 Ev1 2.2.1 Electron Affinity Rule and Band Alignment: How does one figure out the relative alignment of the bands at the junction of two different semiconductors? For example, in the Figure above how do we know whether the conduction band edge of semiconductor 2 should be above or below the conduction band edge of semiconductor 1? The answer can be obtained if one measures all band energies with respect to one value. This value is provided by the vacuum level (shown by the dashed line in the Figure above). The vacuum level is the energy of a free electron (an electron outside the semiconductor) which is at rest with respect to the semiconductor. The electron affinity, denoted by (units: eV), of a semiconductor is the energy required to move an electron from the conduction band bottom to the vacuum level and is a material constant. -

Analysis of Quantum-Well Heterojunction Emitter Bipolar Transistor Design

American Journal of Nano Research and Applications 2020; 8(1): 9-15 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/nano doi: 10.11648/j.nano.20200801.12 ISSN: 2575-3754 (Print); ISSN: 2575-3738 (Online) Analysis of Quantum-well Heterojunction Emitter Bipolar Transistor Design Hsu Myat Tin Swe 1, 2, Hla Myo Tun 1, Maung Maung Latt 2 1Department of Electronic Engineering, Yangon Technological University, Yangon, Myanmar 2Department of Electronic Engineering, Technological University (Taungoo), Taungoo, Myanmar Email address: To cite this article: Hsu Myat Tin Swe, Hla Myo Tun, Maung Maung Latt. Analysis of Quantum-Well Heterojunction Emitter Bipolar Transistor Design. American Journal of Nano Research and Applications . Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 9-15. doi: 10.11648/j.nano.20200801.12 Received : March 16, 2020; Accepted : April 1, 2020; Published : April 13, 2020 Abstract: The paper presents the analysis of Quantum-well Heterojunction Emitted Bipolar Transistor Design based on physical parameters with numerical computations. The specific objective of this work is to enhance the physical performance of the Quantum-well Heterojunction Emitted Bipolar Transistor Design in real world applications. There have been considered on the III-V compound materials like GaAs for p-type layer, AlGaAs for n-type layer and InGaAs for quantum-well layer for different kinds of junctions which were developed in HEBT structure. In this analyses, the parameters for implemented HEBT structure were evaluated to find the multi-quantum-well band diagram, operating frequency (unity beta frequency), rise time, storage delay time, fall time, minority carrier distribution, current gain variation, voltage-current characteristics and phonon control on quantum-well device. -

Semiconductor Lasers (Pdf)

Semiconductor Lasers Direct-Gap vs. Indirect-Gap E(energy) k (momentum) A Brief Introduction to Semiconductors Energy Bands E Conduction band (empty) Eg (bandgap energy) 1 0 Valance band 1 (full) fFD EE f 1 exp kT Equilibrium Fermi-Dirac Statistics http://britneyspears.ac/lasers.htm !!!??? Conduction band Eg Valance band Nonequilibrium Electron-Hole Injection 104 cm-1 Example Gain Gain GaAs Eg=1.4 eV Absorption or or Absorption Absorption (g=850 nm) 0 hw E g Section 12.1 p.2 p-n junctions Doping with Impurities n-type p-type Ef Eg Eg Ef Examples: GaAs doped with Br Examples: GaAs doped with Zn Si doped with P Si doped with Al Semiconductor junction lasers Forward-Biased p-n Junction (LED) n+-GaAs p+-GaAs + V d Inversion (Gain) Layer Neh, ed Current Density Threshold J th r Recombination time Section 12.2 p.2 Edge-Emitting Homojunction Laser Diodes +v Polished facets p-GaAs n-GaAs Lg100 m •Waveguide Modes Homojunction Lasers have very high current threshold mainly because. •Electrons and holes are free to diffuse and therefore dilute the gain (no carrier confinement) •Optical mode has poor overlap with gain (no opticalNeh, ed confinement or guiding) J th r 12.3 Heterojunction Lasers Diodes A fortunate coincidence: n when Eg electrons n+ p+ AlGaAs GaAs AlGaAs Energy Carrier confinement holesholes 100 nm Index of Refraction Mode confinement Section 12.3 p.2 Edge-Emitting Heterojunction Laser Diodes Edge-Emitting Buried Heterojunction Laser Diodes Cleaved reflecting surface W L Stripe electrode Oxide insulator p-GaAs (Contacting lay er) p-Al Ga As (Confining lay er) x 1-x p-GaAs (Active lay er) n-Al Ga As (Confining lay er) 2 x 1-x 1 3 Substrate n-GaAs (Substrate) Current pa thsSubst rate Electrode Elliptic al Cleaved reflecting surface laser Active region where J > J .