It a Case Study of the Sierra Leone Conflict (1985- 2002)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sierra Leone Assessment

Sierra Leone, Country Information http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=...erra%20Leone%2C%20Country%20Information SIERRA LEONE ASSESSMENT April 2002 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES V HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VI HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VII HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1. This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2. The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3. The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4. It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5. An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to the following organisations: Amnesty International UK 1 of 43 07/11/2002 5:44 PM Sierra Leone, Country Information http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=...erra%20Leone%2C%20Country%20Information Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE Medical Foundation for the care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees 2. -

Sierra Leone, Country Information

Sierra Leone, Country Information SIERRA LEONE ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VIA HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1 The Republic of Sierra Leone covers an area of 71,740 sq km (27,699 sq miles) and borders Guinea and Liberia. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE PRESS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE Pupils of Promise Land and Sierra International Schools visited the court yesterday. PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Press and Public Affairs Office as at Thursday, 15 June 2006 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston -Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News At Special Court … Kabbah 2 - Norman 1 / Exclusive Page 3 Kabbah Escapes Special Court / Awoko Page 4 Special Court Declines Kabbah’s Appearance / Christian Monitor Page 5 President of Sierra Leone Will not be Forced to Testify … / Awareness Times Page 6 Decision of the Special Court for Sierra Leone on Norman & Fofana Subpoena …/ Awareness… Page 6 International News Britain Says Would Jail Former Liberian Warlord Charles Taylor if Convicted / Reuters Page 7 UK Agrees to Jail Charles Taylor / BBC Online Page 8 Special Court : Subpoena Against Kabbah Denied! / Patriotic Vanguard website Page 9 Encouraging Progress Seen in Liberia but Security Remains Fragile says Annan / UN News Page 10 Taylor’s Men Besiege Party Headquarters / African News Dimension Page 11 UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary / UNMIL Pages 12 – 15 Prosecutor in UN-backed War Crimes Court Sees Multiple Darfur Prosecutions / UN News Page 16 3 Exclusive Thursday, 15 June 2006 4 Awoko Thursday, 15 June 2006 5 Christian Monitor Thursday, 15 June 2006 Special Court Declines Kabbah’s Appearance 6 Awareness Times (Online Edition) Wednesday, 14 June 2006 http://news.sl/drwebsite/publish/printer_20052716.shtml Breaking News President of Sierra Leone will not be forced to testify in front of Special Court By Awareness Times Wednesday, 14 June 2006 The Special Court for Sierra Leone has reached a decision on the Moinina Fofana / Hingha Norman motion to subpoena the President of Sierra Leone, His Excellency Alhaji Dr. -

Internship Final Report

UNICEF ROLE TO OVERCOME THE RECRUITMENT OF CHILDREN SOLDIER IN ARMED CONFLICT STATE: STUDY ON SIERRA LEONE CIVIL WAR 1991-2002 By Dyah Ayu Antik Arjanti 016201100101 A thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities President University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Bachelor’s Degree in international Relations Major in Diplomacy Studies 2015 THESIS ADVISER RECOMMENDATION LETTER This thesis entitled “UNICEF ROLE IN OVERCOME THE IMPACT OF CHILD SOLDIERS RECRUITMENT IN ARMED CONFLICT STATE: STUDY ON SIERRA LEONE CIVIL WAR 1991-2002" prepared and submitted by Dyah Ayu Antik Arjanti in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of (title degree) in the Faculty of Business and International Relations has been reviewed and found to have satisfied the requirements for a thesis fit to be examined. I therefore recommend this thesis for Oral Defense. Cikarang, Indonesia, 28 January 2015 Dr. Endi Haryono, M.Si DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I declare that this thesis, entitled “UNICEF ROLE IN OVERCOME THE IMPACT OF CHILD SOLDIERS RECRUITMENT IN ARMED CONFLICT STATE: STUDY ON SIERRA LEONE CIVIL WAR 1991-2002" is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, an original piece of work that has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, to another university to obtain a degree. Cikarang, Indonesia, 28 January 2015 Dyah Ayu Antik Arjanti PRESIDENT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, COMMUNICATIONS AND LAW MAJORING INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS (DIPLOMACY) Dyah Ayu Antik Arjanti 016201100101 UNICEF ROLE IN OVERCOME THE IMPACT OF CHILD SOLDIERS RECRUITMENT IN ARMED CONFLICT STATE: STUDY ON SIERRA LEONE CIVIL WAR 1991-2002 ABSTRACT This thesis discusses the role of UNICEF as International Organization in addressing issues of children soldiers in Sierra Leone. -

A Human Rights Audit of the 2018 Sierra Leone Election

Acronyms 1. ACC : ANTI CORRUPTION COMMISSION 2. AG : ATTORNEY GENERAL 3. AUEO : AFRICA UNION ELECTIONS OBSERVER 4. AYV-TV : AFRICA YOUNG VOICES TELEVISION 5. CARL : CENTER for ACCOUNTABILITY and RULE of LAW 6. CJ : CHIEF JUSTICE 7. CWEO : COMMON WEALTH ELECTIONS OBSERVER 8. DOP : DESTRUCTION OF PROPERTY 9. ECOWAS : ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICA STATES 10. EISA : ELECTORAL INSTITUTE for SUSTAINABLE DEMOCRACY in AFRICA 11. EUEO : EUROPEAN UNION ELECTIONS OBSERVER 12. HRC-SL : HUMAN RIGHT COMMISSION-SL 13. HRDN-SL : HUMAN RIGHT DEFENDERS NETWORK-SL 14. HURIDAC : HUMAN RIGHT ADVANCEMENT, DEVELOPMENT and ADVOCACY CENTER 15. KKK : KILLER KILL KILLER 16. MIA : MINISTRY of INTERNAL AFFAIRS 17. NATCOM : NATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION 18. NEC : NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION 19. NEW : NATIONAL ELECTIONS WATCH 20. OHCHR : OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER for HUMAN RIGTH 21. PPRC : POLITICAL PARTY REGISTRATION COMMISSION 22. SLAJ : SIERRA LEONE ASSOCIATION of JOURNALISTS 23. SLBA : SIERRA LEONE BAR ASSOCIATION 24. SLBC-TV : SIERRA LEONE BROADCASTING CORPORATION 25. SLP : SIERRA LEONE POLICE 26. UNEO : UNITED NATIONS ELECTIONS OBSERVERS 27. WANEP : WEST AFRICA NETWORK for PEACEBUILDING 28. WSR-SL : WOMEN SITUATION ROOM-SL 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This report on Human Rights Audit of Sierra Leone 2018 General Elections has been produced by the Human Rights Defenders Network – SL (HRDN-SL) and Human Rights, Advancement, Development and Advocacy Centre (HURIDAC) The human rights examination of 2018 general elections is necessary as a critical link to the right to vote. This encompasses other human rights such as freedom of association and of expression and many others. Advocating for the right to vote is essential to ensuring the „will of the people‘ counts during elections. -

War and the Crisis of Youth in Sierra Leone

This page intentionally left blank War and the Crisis of Youth in Sierra Leone The armed conflict in Sierra Leone and the extreme violence of the main rebel faction – the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) – have challenged scholars and members of the international community to come up with explanations. Up to this point, though, conclusions about the nature of the war and the RUF are mainly drawn from accounts of civilian victims or based on interpretations and rationalisations offered by commentators who had access to only one side of the war. The present study addresses this currently incomplete understanding of the conflict by focusing on the direct experiences and interpretations of protagonists, paying special attention to the hitherto neglected, and often underage, cadres of the RUF. The data presented challenge the widely canvassed notion of the Sierra Leone conflict as a war motivated by ‘greed, not grievance’. Rather, it points to a rural crisis expressed in terms of unresolved tensions between landowners and marginalised rural youth – an unaddressed crisis of youth that currently manifests itself in many African countries – further reinforced and triggered by a collapsing patrimonial state. Krijn Peters, a rural development sociologist by background, is a lec- turer in the Department of Political and Cultural Studies at Swansea University, Wales. He specialises in armed conflict and post-war recon- struction, focusing primarily on the disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration of child soldiers and youthful combatants. Peters is the co-author of War and Children (2009) and a Visiting Fellow at VU University, Amsterdam. Advance Praise for War and the Crisis of Youth in Sierra Leone ‘This book goes more deeply into an understanding of RUF fighters – their beliefs and their atrocities – than previous studies. -

CDF Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2004-14-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. SAM HINGA NORMAN MOININA FOFANA ALLIEU KONDEWA WEDNESDAY, 31 MAY 2006 9.50 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER I Before the Judges: Pierre Boutet, Presiding Bankole Thompson Benjamin Mutanga Itoe For Chambers: Ms Roza Salibekova For the Registry: Ms Maureen Edmonds For the Prosecution: Mr Joseph Kamara Mr Mohamed Bangura Ms Miatta Samba Ms Wendy van Tongeren For the Principal Defender: Mr Lansana Dumbuya For the accused Sam Hinga Dr Bu-Buakei Jabbi Norman: Mr Aluseine Sesay For the accused Moinina Fofana: Mr Arrow Bockarie Mr Andrew Ianuzzi For the accused Allieu Kondewa: Mr Ansu Lansana NORMAN ET AL Page 2 31 MAY 2006 OPEN SESSION 1 [CDF31MAY06A - RK] 2 Tuesday, 31 May 2006 3 [The accused present] 4 [The witness entered court] 09:45:40 5 [Open session] 6 [Upon commencing at 9.50 a.m.] 7 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning, counsel. Good morning, 8 Mr Witness. Dr Jabbi. 9 MR JABBI: Good morning, My Lord. 09:52:07 10 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. Where are we in the 11 presentation of your evidence and, before we do, let me just 12 allow me to state for the record that this morning there appears 13 to be no representation by counsel for the third accused in 14 court. 09:52:27 15 JUDGE ITOE: And even for the second. 16 PRESIDING JUDGE: I was going to the second. Thank you, my 17 dear friend, even for the second accused. We know that 18 Mr Ianuzzi is there, but he is not authorised to be acting for 19 the accused. -

Armed Forces Revolutionary Council Press Release 18 July1997

Armed Forces Revolutionary Council Press Release 18 July1997 The attention of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council Secretariat has been drawn to a publication in the New Tablet Newspaper of 18th July, 1997 captioned, "485 Sojas" of the Republic of Sierra Leone Military forces and the People's Army have voluntarily given themselves up to the ECOMOG. This baseless and unfounded information is deliberately meant to incite members of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Sierra Leone and the People's Army. This blatant act of propaganda are the handiwork of unpatriotic citizens parading as journalists who are bent on creating fear and panic in the minds of the people. The Armed Forces Revolutionary Council Secretariat, therefore wishes it to be known that no such surrender was done by any member of the Armed Forces or the People's Army who still in their entirety continue to demonstrate their loyalty to the government and the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council in compliance with the oath taken to serve the government of the day, and to defend the territorial integrity and sovereignty of our republic at all times. The Armed Forces Revolutionary Council wishes to assure the general public that, the security of the state is paramount in their agenda to bring sustainable and permanent peace to Sierra Leone. It has also been discovered that the said newspaper is not registered and detailed information including telephone numbers were deliberately omitted which clearly demonstrates that the said newspaper is operating contrary to the rules and regulations for the registration of newspapers. Armed Forces Revolutionary Council Press Release 3 November 1997 TEJAN KABBAH SELLS NATION'S DIAMOND (SIX HUNDRED AND TWENTY CARATS) Reports reaching the A.F.R.C. -

The Case of Sierra Tenne

3 Are "Forest" Wars in Africa Resource Conflicts? The Case of Sierra tenne Paul Richards Until Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, African wars were wars of in dependence. During the 1980s the continent's conflicts mainly were deter mined by the Cold War or apartheid in South Africa. The 1990S saw a rise in African conflicts escaping earlier categorizations (Chabal and Daloz 1999; Goulding 1999). Seeking to account for these recent conflicts, au thors have opted for either the idea of reversion to a long-suppressed African barbarity (Kaplan 1994, 1996) or the notion of a "criminalization of the African state" (Bayart, Ellis, and Hibou 1997). Duffield (1998) shrewdly notes, however, that current or recent African wars fall, more or less, into two regional groupings: wars from the Horn of Africa to Mozambique that are in effect "old" proxy conflicts, perhaps pro longed by humanitarian interventions, and conflicts in the western half of the continent (from Zaire to Liberia) sustained by abundant local natural resources (oil, gemstones, gold, and timber). Stretching a point, we might label these two groupings "desert" and "forest" wars, respectively. Some recent literature treats African "forest" wars as predominantly eco nomic phenomena, directed by "war-lord" business elites (Berdal and Keen 1997; Chabal and Daloz 1999; Duffield 1998); the opportunist Charles Taylor in Liberia is seen as the paradigmatic protagonist (Reno 1997; Ellis 1999). All conflicts need resources, but we should be careful to distinguish the plausible idea that war has economic dimensions from the more contentious notion that resource endowments, and in particular re source shortages, "cause" violence (Homer-Dixon 1991, 1994; Kaplan 1994, 1996). -

SIERRA-LEONE ASSESSMENT Oct2002

SIERRA-LEONE COUNTRY ASSESSMENT APRIL 2003 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION AND NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE Home Office, United Kingdom Sierra Leone-April 2003 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the document 1.1 – 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 – 4.2 5 State Structures The Constitution 5.1 – 5.2 Citizenship 5.3 – 5.5 Political System 5.6 – 5.8 Judiciary 5.9 – 5.13 Legal Rights/Detention 5.14 Death Penalty 5.15 Internal Security 5.16 – 5.19 Border security and relations with neighbouring countries 5.20 – 5.22 Prison and Prison Conditions 5.23 – 5.25 Armed Forces 5.26 – 5.29 Military Service 5.30 Medical Services 5.31 – 5.34 People with disabilities 5.35 – 5.36 5.37 – 5.38 Educational System 6 Human Rights 6a. Human Rights issues Overview 6.1 – 6.2 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.3 – 6.8 Journalists 6.9 – 6.10 Freedom of Religion 6.11 – 613 Religious Groups 6.14 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.15 – 6.18 Employment Rights 6.19 – 6.23 People Trafficking 6.24 – 6.26 Freedom of Movement 6.27 – 6.28 Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) 6.29 – 6.32 6b. Human rights – Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.33 – 6.36 Women 6.37 – 6.40 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 6.41 – 6.45 Children 6.46 – 6.52 Child Care Arrangements 6.53 – 6.54 Homosexuals 6.55 Revolutionary United Front (RUF) 6.56 – 6.61 6.62 – 6.63 Civil Defence Forces (CDF) 6c. -

A Comparative Analysis of Post-Conflict Peacebuilding in Liberia and Sierra Leone, 2000-2013

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POST-CONFLICT PEACEBUILDING IN LIBERIA AND SIERRA LEONE, 2000-2013 BY AKHAZE, RICHARD EHIS. MATRIC NO: 950104031 B.A., M.A. (LAGOS) BEING A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POST GRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN HISTORY AND STRATEGIC STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS JUNE 2015 SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LAGOS CERTIFICATION This is to certify that the Thesis: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POST-CONFLICT PEACEBUILDING IN LIBERIA AND SIERRA LEONE 2000-2013 Submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies University of Lagos For the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) is a record of original research carried out By: AKHAZE, RICHARD EHIS. In the Department of History and Strategic Studies ……………………………. …………………… ………………… AUTHOR’S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………. ………………….. ………………… 1ST SUPERVISOR’S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ……………………………… …………………. …………………. 2ND SUPERVISOR’S NAME SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………. ………………… …………………. 1ST INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ……………………………….. ………………… ………………… 2ND INTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………. ………………… ………………… EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ………………………………. ………………… ………………… SPGS REPRESENTATIVE SIGNATURE DATE ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God and the memory of my Parents Mr. and Mrs. Willie Iseghohi Akhaze. They were my greatest inspiration for academic pursuit. They were an embodiment of intelligence, selflessness, hard work, integrity, perseverance and farsightedness. iii ABSTRACT This study examines the nature and structure of post-conflict peacebuilding in Liberia and Sierra Leone since 2000. It focuses specifically on peacebuilding process in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Previous researches on peacebuilding as a tool of conflict management have generated a lot of questions in academic circles. -

Home Office, from Information Obtained from a Variety of Sources

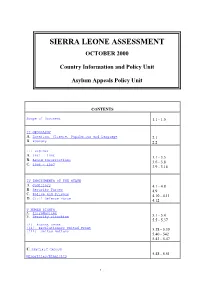

SIERRA LEONE ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit Asylum Appeals Policy Unit CONTENTS Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY A. Location, Climate, Population and Language 2.1 B. Economy 2.2 III HISTORY A. 1961 - 1996 3.1 - 3.5 B. Armed Insurrections 3.6 - 3.8 C. 1996 - 1997 3.9 - 3.16 IV INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE A. Judiciary 4.1 - 4.8 B. Security Forces 4.9 C. Police and Prisons 4.10 - 4.11 D. Civil Defence Force 4.12 V HUMAN RIGHTS A. Introduction B. Security situation 5.1 - 5.4 5.5 - 5.37 (i). Recent event (ii). Revolutionary United Front (iii). United Nations 5.38 - 5.39 5.40 - 542 5.43 - 5.47 C. SPECIFIC GROUPS 5.48 - 5.51 Minorities/Ethnicity 1 5.52 - 5.57 Women 5.58 - 5.62 Children OTHER ISSUES Freedom of Association and Assembly Freedom of the Press 5.63 Freedom of Religion 5.64 - 5.69 Freedom to Travel and Internal Flight 5.70 - 5.72 5.73 - 5.75 ANNEX A: Common Abbreviations/Political Parties ANNEX B: Prominent People ANNEX C: Chronology of Major Events Bibliography 2 I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations.