Dan Hutt 6/17/08 Uses of WWI Imagery in the Late 60'S Pop Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arista Careers Interworld

WHO'S WHO AT ARISTA-CAREERS/INTERWORLD INTERVIEW WITH BILLY MESHEL Q: Alright Billy, tell me about the development of the publishing operation. :A: Well, in January 1977 the publishing company was set up. Q: The record company was established when? A: I think the record company was 3 years old...We started with no songs in the catalogue. Our first deal was with Gregg Diamond and "More, More, More" was the first song that we had that made money...it went to number one. That went on to become a real good relationship and gave us some good songs to exploit. Q: You started by looking for writers rather than acquiring catalogues? A: We never look for catalogues...the thing you do is find talented people...catalogues are inflated. Q: Do you feel that even back in '77 you were better off going after good writers than established catalogues? A: Well, good writer-artists. We couldn't sign straight writers because we didn't have the staff yet. Even now, almost 5 years later, we still don't have enough of a staff to take care of straight writers. We get involved mainly with writer-artists who we believe to be talented. Q: What else is important besides signing good writer-artists? A: The next thing when you are starting up a company is individual songs. So you listen to everything that comes in. Before we had anyone working for us I listened to all of the tapes myself. I found "Hard Times For Lovers", the song that Judy Collins ultimately did, plus a bunch of other individual songs that way. -

GOOD MORNING: 03/29/19 Farm Directionанаvan Trump Report

Tim Francisco <[email protected]> GOOD MORNING: 03/29/19 Farm Direction Van Trump Report 1 message The Van Trump Report <reply@vantrumpreportemail.com> Fri, Mar 29, 2019 at 7:14 AM ReplyTo: Jordan <replyfec01675756d0c7a314_HTML362509461000034501@vantrumpreportemail.com> To: [email protected] "Smooth seas do not make skillful sailors." African proverb FRIDAY, MARCH 29, 2019 1776, Putnam Named Printable Copy or Audio Version Commander of New York Troops On this day in 1776, Morning Summary: Stocks are slightly higher this morning but continue to consolidate General George Washington into the end of the first quarter, where it will post its best start to a new year since appoints Major General Israel 1998. It seems like the bulls are still trying to catch their breath after posting the Putnam commander of the troops in New massive rebound from December. The S&P 500 was up over +12% in the first quarter York. In his new capacity, Putnam was of 2019. We've known for sometime this would be a tough area technically. There's also expected to execute plans for the defense the psychological wave of market participants trying to get off the ride at this level, of New York City and its waterways. A having recouped most of what they lost in late2018. I mentioned many weeks ago, if veteran military man, Putnam had served we made it back to these levels it would get very interesting, as those who took the as a lieutenant in the Connecticut militia tumble would have an opportunity to get out of the market with most of their money during the French and Indian War, where back in their account. -

Jon Batiste and Stay Human's

WIN! A $3,695 BUCKS COUNTY/ZILDJIAN PACKAGE THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 6 WAYS TO PLAY SMOOTHER ROLLS BUILD YOUR OWN COCKTAIL KIT Jon Batiste and Stay Human’s Joe Saylor RUMMER M D A RN G E A Late-Night Deep Grooves Z D I O N E M • • T e h n i 40 e z W a YEARS g o a r Of Excellence l d M ’ s # m 1 u r D CLIFF ALMOND CAMILO, KRANTZ, AND BEYOND KEVIN MARCH APRIL 2016 ROBERT POLLARD’S GO-TO GUY HUGH GRUNDY AND HIS ZOMBIES “ODESSEY” 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. It is the .580" Wicked Piston!” Mike Mangini Dream Theater L. 16 3/4" • 42.55cm | D .580" • 1.47cm VHMMWP Mike Mangini’s new unique design starts out at .580” in the grip and UNIQUE TOP WEIGHTED DESIGN UNIQUE TOP increases slightly towards the middle of the stick until it reaches .620” and then tapers back down to an acorn tip. Mike’s reason for this design is so that the stick has a slightly added front weight for a solid, consistent “throw” and transient sound. With the extra length, you can adjust how much front weight you’re implementing by slightly moving your fulcrum .580" point up or down on the stick. You’ll also get a fat sounding rimshot crack from the added front weighted taper. Hickory. #SWITCHTOVATER See a full video of Mike explaining the Wicked Piston at vater.com remo_tamb-saylor_md-0416.pdf 1 12/18/15 11:43 AM 270 Centre Street | Holbrook, MA 02343 | 1.781.767.1877 | [email protected] VATER.COM C M Y K CM MY CY CMY .350" .590" .610" .620" .610" .600" .590" “It is balanced, it is powerful. -

Albright & O'malley Pre-CRS Dungan

February 8, 2010 Issue 178 Dungan: Lady A Sales Are Nuts HOLIDAY SC H EDULE Last week’s No. 1 all-genre debut of Lady Country Aircheck will be closed Monday, Feb. 15 in observance Antebellum’s Need You Now was fueled by of the President’s Day holiday. All Country Aircheck Mediabase a huge single, some crossover airplay and a monitored reporters can submit station adds any time from this national stage television performance, but Thursday (2/11) until 3pm ET/Noon PT on Tuesday, Feb. 16. Country Aircheck non-monitored Activator reporters may submit their 480,000 sold still caught some in the industry full reports any time during that same time frame. The Country by surprise. Country Aircheck spoke with Aircheck Weekly will be delivered Tuesday evening, Feb. 16. Capitol/Nashville President/CEO Mike Dungan for the stories behind the big story. When did you know it had the potential to be that big? Albright & O’Malley pre-CRS It was like losing your mind. It was gradually, then suddenly. McVay New Media Pres. Daniel That’s a quote. It felt big from the day we took it to Country Anstandig, dmr Pres./COO Tripp radio, certainly, and that it would be big with or without this Eldridge and Jaye Albright and Phillip pop exposure we had. Over the Thanksgiving weekend we Beswick are the newest additions to noticed some key pop stations were just playing it. With all this Albright & O’Malley’s annual pre-CRS consolidation, these guys are right next to each other and many Client Seminar. -

23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie Novel in a Poll in September 2015

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 17 – 23 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 17 FEBRUARY 2018 Episode Five Agatha Christie novel in a poll in September 2015. Mary Ann has an unwelcome encounter with a presence from Directed by Mary Peate. SAT 00:00 BD Chapman - Orbiter X (b0784dyd) her past. Shawna is upset by Michael's revelation. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2010. Inside the Moon StationDr Max Kramer has tricked the crew of Dramatised by Lin Coghlan SAT 07:30 Byzantium Unearthed (b00dxdcs) Orbiter 2, but what exactly is Unity up to on the Moon? Producer Susan Roberts Episode 1Historian Bettany Hughes begins a series that uses the BD Chapman's adventure in the conquest of space in 14 parts. Director Charlotte Riches latest archaeological evidence to learn more about the empire of Stars John Carson as Captain Bob Britton, Andrew Crawford as For more than three decades, Armistead Maupin's Tales of the Byzantium and the people who ruled it. Captain Douglas McClelland, Barrie Gosney as Flight Engineer City series has blazed a trail through popular culture-from Bettany learns how treasures found in the empire's capital, Hicks, Donald Bisset as Colonel Kent, Gerik Schelderup as Max ground-breaking newspaper serial to classic novel. Radio 4 are modern-day Istanbul, reveal much about the life and importance Kramer, and Leslie Perrins as Sir Charles Day. With Ian Sadler dramatising the full series of the Tales novels for the very first of a civilisation that, whilst being devoutly Christian and the and John Cazabon. -

QUIET, to See That Most Hit Records Contain Hit In- Tion of Greatest Hits

an old, rusty guitar. But there must be a Promise Suite; Grind It Out; seven more. [Mi- way of presenting such an artist tastefully chael Mainieri, prod.] JUST SUNSHINE REC- and without overpowering him. M.J. ORDS JSS 3, $6.98. Those who apply some objectivity are able ARGENT: The Argent Anthology: A Collec- QUIET, to see that most hit records contain hit in- tion of Greatest Hits. Rod Argent, Russ Bal- gredients of one sort or another. But some- lard, Robert Henrit, and Jim Rodford, vocals times those ingredients are present and yet, and instrumentals. God Gave Rock and Roll to through some mistake, a hit is missed. Nick You; Hold Your Head Up; Liar; Pleasure; It's Only Money, Part I; Thunder and Lightning; Holmes's "Soulful Crooner" strikes me as such an instance. Tragedy; Time of the Season. [Rod Argent PLUS and Chris White, prod.] EPIC PE 33955, "Mistake" really isn't the right word $6.98. Tape: MR PET 33955, $7.98; 0_1.: PEA here, for the problem is much simpler: a Wemade the Phase Linear 4000 33955, $7.98. case of business or street difficulties.I Preamplifier dead quiet, but we never received a review copy of the record, didn't stop there. We added several nor did I hear a word about Nick Holmes, Rod Argent formed Argent out of the ashes revolutionary features that make of the Zombies, one of the "British inva- not even from my sources in the teenage un- music sound obviously better than sion" groups that assaulted these shores in derground, and teenagers know what's hot any other control console: the wake of the Beatles a dozen years ago. -

The Zombies, “Odessey & Oracle: the 40Th Anniversary Concert”

DVD Review: The Zombies, "Odessey & Oracle (Revisited)" | Popdose http://popdose.com/dvd-review-the-zombies-odessey-oracle-the-40th-ann... MUSIC | FILM | TV | THEATRE | CURRENT EVENTS | BOOKS | CONSUMERISM | VIDEO GAMES | SHOP Tuesday, December 29th, 2009 SUBSCRIBE DVD Review: The Zombies, “Odessey & Oracle: The 40th RSS | Email Anniversary Concert” ABOUT POPDOSE by Ken Shane Site Information Staff List In June of 1967, the Zombies entered EMI’s Abbey Road studios to record their masterpiece, Odessey & Oracle . Earlier HEAR POPDOSE that year, the Beatles had recorded their own masterpiece, Sgt. The Popdose Podcast Popdose on Overnight America Pepper , in the same studio. In November, the Zombies completed their sessions, but by then the band was close to the STALK POPDOSE breaking point. Tempers flared during the recording of “Time of On Twitter: the Season,” which later became a massive hit. When keyboard Freedy Johnston talks about his player Rod Argent and bassist Chris White, who had produced new album, his long hiatus, and his outlook on the music biz: the album and written the songs, delivered the mono masters to http://bit.ly/697zRW 10 minutes ago CBS, they were told that stereo masters would be required. They were out of money, and had to take money out of their Be our Facebook fan! own songwriting royalties to pay for the new mixes. It was the BLOGROLL last straw. Singer Colin Blunstone and guitarist Paul Atkinson 3 Minutes 49 Seconds left the band. The stereo mix was completed on January 1, 1968, but by then the Zombies had broken AM, Then FM up. -

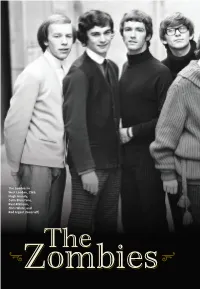

Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (From Le )

The Zombies in West London, 1965: Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Chris White, and Rod Argent (from le ) > The > 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev1_70-95.pdfZombies 1 3/11/19 5:19 PM his year’s induction of the Zombies into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is at once a celebration and a culmina- tion of one of the oddest and most convoluted careers in the history of popular music. While not the first band to have two smash hits right out of the box, they may be the only group who pro- ceeded to then fail miserably with their next ten sin- gles over a three-year period before finally achieving immortality with an album, Odessey [sic] and Oracle (1968) and a single, “Time of the Season,” that were released only after they had broken up. Even then, it would be a year after the album’s ini- tial release that, through the intercession of fate and Tthe idiosyncratic tastes of a handful of radio listeners in Boise, Idaho, “Time of the Season” would become a million-selling single and remain one of the most beloved staples of classic-rock radio to this day. Even more ironic was the fact that, despite that hit single, the album Odessey and Oracle was still met with indif- ference. Decades later, succeeding generations of crit- ics and an ever-growing cult fan base raised Odessey and Oracle to its status as one of the most cherished and revered albums of late 1960s British rock. As the album approached its fiftieth anniversary, four of the five original Zombies (guitarist Paul Atkinson passed away in 2004) went on tour, playing it in its entirety for sellout crowds throughout North America and the United Kingdom. -

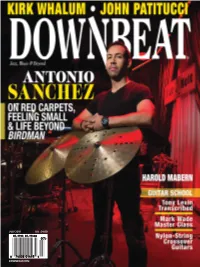

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Artbook | D.A.P

ARTBOOK | D.A.P. 75 Broad Street Suite 630 New York NY 10004 tel (212) 627 1999 fax (212) 627 9484 Spring/Summer 2017 Title Supplement Alice Neel: Uptown By Hilton Als. Foreword by Jeremy Lewison. Known for her portraits of family, friends, writers, poets, artists, students, singers, salesmen, activists and more, Alice Neel (1900–1984) created forthright, intimate and, at times, humorous paintings that both overtly and quietly engaged with political and social issues. In Alice Neel, Uptown, writer and cura- tor Hilton Als brings together a body of paintings of African-Americans, Latinos, Asians and other people of color for the first time. Highlighting the innate diversity of Neel’s approach, the selection looks at those often left out of the art-historical canon and how this extraordinary painter captured them; “what fascinated her was the breadth of humanity that she encountered,” Als writes. The publication explores Neel’s interest in the ex- traordinary diversity of 20th-century New York City and the people among whom she lived. This group of portraits includes well-known figures such as playwright, actress, and author Alice Childress; the sociologist Horace R. Cayton, Jr.; the community activist Mercedes Arroyo; and the widely published academic Harold Cruse; alongside those of more anonymous individuals, such as a nurse, a ballet dancer, a taxi driver, a businessman, a local boy who ran errands for Neel, and other children and their families. In short and illuminating texts on specific works writ- ten in his characteristic narrative style, Als writes about the history of each sitter and offers insights into Neel and her work, while adding his own perspec- tive. -

Lobo Calumet Mp3, Flac, Wma

Lobo Calumet mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Calumet Country: US Released: 1973 Style: Soft Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1761 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1231 mb WMA version RAR size: 1732 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 327 Other Formats: RA DXD AAC XM VQF VOX AUD Tracklist A1 How Can I Tell Her 4:17 A2 Stoney 3:43 A3 Rock And Roll Days 3:58 A4 One And The Same Thing 4:01 A5 Hope You're Proud Of Me Girl 3:00 B1 Love Me For What I Am 4:02 B2 Try 3:10 B3 It Sure Took A Long, Long Time 3:06 B4 Standing At The End Of The Line 3:53 B5 Goodbye Is Just Another Word 3:34 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Bell Records Recorded At – Mastersound Studios, Atlanta Published By – Kaiser Music Inc. Published By – Famous Music Corporation Distributed By – Bell Records Credits Acoustic Guitar – Lobo Backing Vocals – Lobo , Michael Gately, Robert John, Steven Carlisle*, Sue Ellis Bass – John Mulkey Design [Tepee Graphics] – David Larkham Drums, Percussion – Roy Yeager Electric Guitar – Barry Harwood Engineer – Bob Richardson Organ, Piano – Jim Ellis Photography By – Ed Caraeff Producer – Phil Gernhard Strings [Arrangement] – John Abbott, Phil Gernhard Written-By – Lobo Notes Exclusively distributed by Bell Records. A division of Columbia Pictures Industries Inc. N.Y.C. Printed in USA Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: BT2101A-1-11-11 Matrix / Runout: BT2101B-1-11-11 7R Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year BT 2101 Lobo Calumet (LP, Album, Bes) Big Tree Records BT 2101 US 1973 -

Download PDF Version

Part V Abstraction We've really been talking about abstraction all along. Whenever you ®nd yourself performing several similar computations, such as > (sentence 'she (word 'run 's)) (SHE RUNS) > (sentence 'she (word 'walk 's)) (SHE WALKS) > (sentence 'she (word 'program 's)) (SHE PROGRAMS) and you capture the similarity in a procedure (define (third-person verb) (sentence 'she (word verb 's))) you're abstracting the pattern of the computation by expressing it in a form that leaves out the particular verb in any one instance. In the preface we said that our approach to computer science is to teach you to think in larger chunks, so that you can ®t larger problems in your mind at once; ªabstractionº is the technical name for that chunking process. In this part of the book we take a closer look at two speci®c kinds of abstraction. One is data abstraction, which means the invention of new data types. The other is the implementation of higher-order functions, an important category of the same process abstraction of which third-person is a trivial example. 278 Until now we've used words and sentences as though they were part of the natural order of things. Now we'll discover that Scheme sentences exist only in our minds and take shape through the use of constructors and selectors (sentence, first, and so on) that we wrote. The implementation of sentences is based on a more fundamental data type called lists. Then we'll see how lists can be used to invent another in-our-minds data type, trees.