Modernity and the Matrix of Family Ideologies: How Women Compose a Coherent Narrative of Multiple Identities Over the Life Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Je T'aime, Paris!

12 February 2020 JE T’AIME, PARIS! THE PENINSULA PARIS PLAYS A STARRING ROLE ON AN ALL-NEW EPISODE OF ABC’S ‘MODERN FAMILY’ Photo credit: ABC* Terrace of Rooftop Garden Suite at The Peninsula Paris Over the last 11 seasons, the Pritchett-Dunphy-Tucker clan has travelled the globe, making hilarious memories wherever they went – from Hawaii, Australia, Wyoming and Disneyland to Las Vegas, Lake Tahoe and New York. In one last family trip, the crew heads to Paris, so Jay can accept a lifetime achievement award for his work in the closet industry. While there, Claire has a secret rendezvous with an old flame in one of the most romantic spots, atop The Peninsula Paris in a luxurious Rooftop Garden Suite overlooking the Eiffel Tower and Parisian skyline. In a pivotal scene, Claire is introduced to the glamour and romance of The Peninsula as her former love interest seeks to win her affections. The final scene in the episode sees the family united to celebrate at the Michelin-starred L’Oiseau Blanc, enjoying the marvelous food and unbeatable views of The Peninsula Paris’s celebrated rooftop restaurant. The all-new episode of “Modern Family,” titled “Paris,” aired Wednesday, 12 February from 9:00-9:31 p.m. EST on ABC. THE PENINSULA PARIS HAS A STARRING ROLE ON AN ALL-NEW EPISODE OF ABC’S ‘MODERN FAMILY,’ AIRING WEDNESDAY, FEB. 12 In celebration of this special episode and the upcoming Valentine’s Day, The Peninsula Paris invites guests to create their own Modern Romance in Paris, or at some of the Peninsula Hotels around the world, valid from -

Kelly Mantle

The VARIETY SHOW With Your Host KELLY MANTLE KELLY MANTLE can be seen in the feature film Confessions of a Womanizer, for which they made Oscars history by being the first person ever to be approved and considered by The Academy for both Supporting Actor and Supporting Actress. This makes Kelly the first openly non-binary person to be considered for an Oscar. They are also featured in the movie Middle Man and just wrapped production on the upcoming feature film, God Save The Queens in which Kelly is the lead in. TV: Guest-starred on numerous shows, including Lucifer, Modern Family, Curb Your Enthusiasm, CSI, The New Normal, New Adventures of Old Christine, Judging Amy, Nip/Tuck, Will & Grace, George Lopez. Recurring: NYPD Blue. Featured in LOGO’s comedy special DragTastic NYC, and a very small co-star role on Season Six of RuPaul's Drag Race. Stage: Kelly has starred in more than 50 plays. They wrote and starred in their critically acclaimed solo show,The Confusion of My Illusion, at the Los Angeles LGBT Center. As a singer, songwriter, and musician, Kelly has released four critically acclaimed albums and is currently working on their fourth. Kelly grew up in Oklahoma like their uncle, the late great Mickey Mantle. (Yep...Kelly's a switch-hitter, too.) Kelly received a B.F.A. in Theatre from the University of Oklahoma and is a graduate of Second City in Chicago. https://www.instagram.com/kellymantle • https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0544141/ ALEXANDRA BILLINGS is an actress, teacher, singer, and activist. -

By: Bella M. Julia G

View Online at ‐ http://www.glencoewest.org/ Kidsview Issue #2 – March 2011 March 2011 KIDSVIEW Ben G. Yael S. Bella M. Stella K. By: Kinar P. Bridget H. Annie H. Recently Glencoe got two feet of Cameron B. snow. The weather forecasters Annika C. predicted a blizzard, and for once, they were right. The Carly S. blizzard hit on Tuesday and Wednesday. Nobody could get Ava P. out of the house! We could not even open our front door! Charlotte N. The power kept going out. The snow kept coming and Beth F. coming. There was no school Wednesday and Thursday. Eden S. Carly L. Some snowdrifts were seven feet high! The snow was above Emily R. my head. Everybody was outside all day long for both of Caroline S. the snow days. It felt like a weekend! Two days later it was Jeff C. the weekend! It kept on snowing until Saturday. There were Charlotte J. big huge snow mountains at the end of the playground Jordan S. blacktop. Kate B. Conor D. It was the best 2 snow days ever! Kelly H. Devan M. Kinar P. Evan P. Martina S. Isabelle R. Max K. By: Bella M. Julia G. During Kidsview we have realized how Maya M. important it is to save our documents. Even though we all Lauren R. saved to the drop folder we still lost some great articles Moriah H. due to technological issues. This is the story of the Madeline S. missing files and the hunt to get them back. Mrs. Salzman Rachel G. -

Nothing but Sounds, Ink-Marks”—Is Nothing Hidden? Must Everything Be Transparent?

Final version published in the Yearbook of the Danish Philosophy Association, 2018 “Nothing but sounds, ink-marks”—Is nothing hidden? Must everything be transparent? Paul Standish (UCL Institute of Education) Abstract Is there something that lies beneath the surface of our ordinary ways of speaking? Philosophy sometimes encourages the all-too-human thought that reality lies just outside our ordinary grasp, hidden beneath the surface of our experience and language. The present discussion concentrates initially on a few connected paragraphs of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations (particularly ##431-435). Wittgenstein leads the reader to the view that meaning is there in the surface of the expression. Yet how adequate is Wittgenstein’s treatment of the sounds and ink-marks, the materiality of the sign? With some reference to Emerson, Stanley Cavell, and Jacques Derrida, my discussion explores how far a more adequate account of the sign can coincide with the claim that nothing is hidden. It exposes phony obsessions with transparency, which in a culture of accountability have had a distorting effect on education and the wider social field. It endorses confidence in the reality of ordinary words. Keywords Language, reality, expression, Wittgenstein, Emerson, Cavell, Derrida I want to pursue the alleged error of thinking that there must be something that lies beneath the surface of our ordinary ways of speaking about our reactions and responses to the world. A popular form of this is found when you are talking to someone and they say in response: “Just wait a minute while I process what you have said.” They are not, as their language more or less makes clear, quite reasonably telling you that they want to think over what you have said: they are informing you of a mental operation, a brain process that needs to be carried out before they can answer.1 There are 1 Such a response is familiar enough. -

All in the Family Season 8 Dvd

All in the family season 8 dvd All 24 Original Half-Hour Episodes from Season Eight of the award-winning television series from Norman Lear earned Emmys for Carroll O'Connor. Season Nine finds Mike and Gloria officially moved out, leaving Archie and Edith on their own for the first time in a long while. Of course, that doesn't last long. All 25 Original Half-Hour Episodes from One of the most acclaimed comedy series of all time, Norman Lears Emmy-winning All In The Family returns. This item:All In The Family: The Complete Series by Carroll O'Connor DVD Sanford and Son: The Complete Series (Slim Packaging) by Redd Foxx DVD. All In The Family The Complete Series Season (DVD ) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9. DVD Release Date: October 30, Run Time: minutes. Number of. item 5 All in the Family: Complete Series Seasons (DVD, Discs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 -All in the Family: Complete Series Seasons (DVD, Discs) 1 2 3 4. All in the Family: Season 8. Title: All in the Family: Season 8. As dark as the plots run at times, the laughs always shine through in this perfectly balanced and. The complete All in the Family DVD series with episodes is now available from Time All In The Family Season 8: 24 Episodes on 3 DVDs. Shop Staples for great deals on All in the Family: Season 8 (DVD). and in stores. 8 New & Used from $ Carol Burnett Show: Carol's Favorites (6 Dvd) Add to Wishlist All in the Family: The Complete Fourth Season. -

Modern Families

1 Trends Shaping Education 2014 Spotlight 6 Modern Families Families in the OECD are changing. The nuclear family – mother and father, married with children –is becoming less common. The number of reconstituted and single- parent households is rising, families are becoming smaller and individuals are deciding to have children later in life, or not at all. Education plays an important role in supporting these modern families as well as traditional ones, and ensuring that learning needs are met for all. Love then Marriage? Over the past 40 years, marriage rates in OECD countries have fallen dramatically, from 8 marriages per 1 000 people in 1970 to only 5 in 2010. As can be seen in Figure 1, the decrease in marriage rates has been particularly pronounced in countries like Hungary, Portugal and Slovenia, where marriage rates declined by more than half in that time (OECD, 2011a). Furthermore, the average age of first marriage (29.7) has risen above the average age of first childbirth (27.7), signalling that more people now have children without getting married (OECD, 2014a). In the same time period, the average divorce rate in the OECD doubled from 1.2 divorces per 1 000 people to 2.4. This has led to a higher number of single-parent and step-parent families. Figure 1: Number of marriages by 1000 people in 1970 and 2010, by country 2010 1970 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Source: OECD (2014), OECD Family Database, OECD, Paris (www.oecd.org/social/family/database) Spotlight 6. MODERN FAMILIES – 2 These demographic changes mean that many children in the OECD now grow up in families that are quite different from the traditional nuclear family. -

Michael Crowley, MS Head/ISB Assistant Director

Twenty Questions to get to know you better: Michael Crowley, MS Head/ISB Assistant Director Mike joined ISB in 1989-90 (taught English and Journalism and since 2001 he has been leading the Middle School). To many alumni and current students, teachers and families, he is known as a wonderful leader, educator and friend! Let’s find out more about him. Nationality: Irish Q1. Where did you grow up? Q6. What makes you laugh? Galway City, in the West of Ireland. Most often, the direct honesty and infectious wit of middle school students. Q2. Where did you live before Brussels? Frasier Crane in any incarnation; most As above, with periodic stays in the recently, Modern Family. majestic Burren, County Clare. Q7. What really gets on your nerves? Q3. What can’t you live without? My Not a lot. I have little time for people family, music, books, an internet who take themselves too seriously, connection, a sense of humour, and a bullies, arrogance, ego maniacs, or steady supply of oxygen. negaholics, but I do not waste energy letting them get on my nerves. What Q4. What is your favorite movie or really gets on my nerves? Caffeine. book of all time? Impossible question! Movie would be Q8. What cartoon character best either One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest describes you? or On The Waterfront. Favourite book is Has got to be Principal Skinner in The Simpsons. even tougher. Favourite writers include Brian Moore, Richard Russo, Larry Q9. Your favorite place in Brussels? McMurtry, Richard Ford, John Updike … Wherever I happen to eat with my but if you forced me to pick one book, it family on a Friday night. -

Gothic Taxonomies: Heredity and Sites of Domestication in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction

GOTHIC TAXONOMIES: HEREDITY AND SITES OF DOMESTICATION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION By Elizabeth M. Pellerito A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English 2012 ABSTRACT GOTHIC TAXONOMIES: HEREDITY AND SITES OF DOMESTICATION IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY BRITISH FICTION By Elizabeth M. Pellerito This project reads the ways in which systems of taxonomy and gothic novels, when read together, chart the history of nineteenth-century theories of heredity. By pitting Enlightenment empiricist and rationalist thought against gothic novels, literary critics have posited the two fields as diametrically opposed entities. However, I argue here that the gothic novel translates naturalists’ and taxonomists’ questions about species, applying them to the social, political and biological structure of the human family. The central term of the project, “gothic taxonomy,” refers to the moments in each of these disciplines, and in the exchanges between them, that describe failed systematizations, the simultaneous necessity and impossibility of nineteenth- century attempts to encapsulate the laws of hereditary transmission in a single set of natural laws. By reading taxonomy as a process with social and political consequences, this project provides much-needed nuance to the often reductive critical debates about hereditarians and their foes during the nineteenth century. Revising and complicating these notions forces us to rethink the gothic as a discourse that is merely oppositional in nature, existing only to challenge the narratives of Enlightenment. Reading the gothic as an interpretive model that actively unpacks the inconsistencies of systematization, rather than simply as a reactionary celebration of the irrational or the subconscious, allows us to read it as a discourse with a real contribution of its own to make to scientific debates about the biological and social role of heredity during the period. -

The Fellows' Forum Globalizing the Modern Family Ideal, by Kathryn M. Yount

6 families that work SPRING 2005 THE FELLOWS’ FORUM GLOBALIZING THE MODERN FAMILY IDEAL Families in the U.S. have undergone dra- consensual marriage preceded by courtship, Working for cash in Egypt has been linked with matic change. In the past three decades, the youthful autonomy, and a high valuation women’s approval of having a say in decisions average size of households declined among of women. related to children, and watching television whites and African Americans and increased Thornton has argued that these beliefs have has been associated with women’s approval among Hispanic Americans. The percentage been disseminated in European colonialism; of influencing other family-related matters. of households headed by married couples in schools in non-Western societies; in the Thornton has argued that a person’s accep- training of non-Westerners at institutions in tance or rejection of developmental ideals can declined from 78 percent to 53 percent in Northwestern Europe and its diasporas; in influence an array of human behaviors, includ- the period from 1950 to 1998 and declined channels of communication, transportation, ing choices about work and family life. Among from 93 percent to 73 percent among fami- and mass media; in national, international, urban and semiurban male residents in Nigeria, lies with children. Among married working and nongovernmental family-planning pro- for example, those believing that men should couples with children, the share of dual- grams; in revolutionary social movements and be dominant in family decisions had an average earning couples rose from 59 percent to 68 the international women’s movement(s). -

Eileen Yam, Phd, Mph

EILEEN YAM, PHD, MPH Professional Experience 2016-present Associate II, Population Council, Washington, DC, USA Deputy Director for Project SOAR, a $50 million USAID-funded global research portfolio focused on HIV implementation science. Provides overall senior management and technical oversight, ensuring quality assurance of technical deliverables; facilitates and supports strategic and technical communications between USAID, global consortium partners, and local partners; and plays a representational role for the project. Led conceptualization and implementation of research on family planning and safer conception needs among HIV-positive women in Tanzania. 2012–2016 Associate I, Population Council, Washington, DC, USA Project Director for a five-country research portfolio on HIV, reproductive health, and gender issues among young key populations in Africa and Asia. Collaborated with program implementers and other stakeholders to identify priority research questions and appropriate study designs. Ensured quality of all study protocols and products. Provided overall strategic guidance as well as managerial and technical leadership for US and international staff, and ensured all activities were completed on time and within budget. Represented the Council to donors, governments, and partners. Served as co-investigator on studies evaluating peer-led programs to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights of young key populations. 2012 Consultant, Institute for Reproductive Health, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA Revised and wrote papers for peer-reviewed publication, including manuscripts on the role of the Standard Days Method® in modern family planning services, and the effects of social networks on contraceptive use in Mali. 2007–2011 Consultant, Population Council, Washington, DC, USA Conducted qualitative and quantitative data analysis for studies on abortion in Mexico, and condom use among Bolivian female sex workers. -

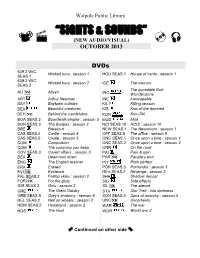

New Audio/Visual) October 2013

Walpole Public Library “SIGHTS & SOUNDS” (NEW AUDIO/VISUAL) OCTOBER 2013 DVDs 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 1 HOU SEAS.1 House of cards : season 1 SEAS.1 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 2 ICE The iceman SEAS.2 The incredible Burt ALI NR Aliyah INC Wonderstone ART Arthur Newman INE Inescapable BAY Baytown outlaws KIL Killing season BEA Beautiful creatures KIS Kiss of the damned BEH NR Behind the candelabra KON Kon-Tiki BOA SEAS.3 Boardwalk empire : season 3 MUD Mud BOR SEAS.3 The Borgias : season 3 NCI SEAS.10 NCIS : season 10 BRE Breakout NEW SEAS.1 The Newsroom : season 1 CAS SEAS.4 Castle : season 4 OFF SEAS.9 The office : season 9 CAS SEAS.5 Castle : season 5 ONC SEAS.1 Once upon a time : season 1 COM Compulsion ONC SEAS.2 Once upon a time : season 2 COM The company you keep ONR On the road COV SEAS.3 Covert affairs : season 3 PAI Pain & gain DEA Dead man down PAR NR Parade’s end ENG The English teacher PIT Pitch perfect ERA Erased POR SEAS.3 Portlandia : season 3 EVI NR Evidence REV SEAS.2 Revenge : season 2 FAL SEAS.2 Falling skies : season 2 SHA Shadow dancer FOR NR For the glory SID Side effects GIR SEAS.2 Girls : season 2 SIL NR The silence GRE The Great Gatsby STA Star Trek : into darkness GRE SEAS.9 Grey’s anatomy : season 9 SON SEAS.5 Sons of anarchy : season 5 HEL SEAS.2 Hell on wheels : season 2 UNC NR Uncertainty HOM SEAS.2 Homeland : season 2 WAR The war HOS The Host WOR World war Z Continued on other side 2 Walpole Public Library NEW AUDIO/VISUAL 2013 Books on CD Manson : the life and Refusal 364.1523 MAN times of -

10 BOLD June 6

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 06th June 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Bondi Rescue (Rpt) CC PG Coarse Language, A man is dragged unconscious from the water and without a pulse. Mature Themes Reidy and Beardy attach the defibrillator and oxygen mask and begin resuscitation. Can the boys bring him back? 08:30 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Caretaker, Part 1 Violence Under the command of Captain Kathryn Janeway the starship Voyager is transported 70,000 light years from home into the uncharted region of the galaxy known as the Delta Quadrant. Starring: Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Robert Duncan McNeill 09:30 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Caretaker, Part 2 Mild Violence Captain Janeway and Chakotay, leader of the Maquis ship band together to find their missing crewmen with the help of the Talaxian, Neelix, and the Ocampa, Kes. Starring: Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Robert Duncan McNeill 10:30 am Escape Fishing With ET (Rpt) CC Escape with former Rugby League Legend "ET" Andrew Ettingshausen as he travels Australia and the Pacific, hunting out all types of species of fish, while sharing his knowledge on how to catch them. 11:00 am Scorpion (Rpt) CC PG Hard Knox Mild Violence, The Department of Defense hires the team to break into Fort Knox and Mild Coarse Language steal an artefact in order to test their security system, but their biggest threat could be what is hidden inside the object.