Russia Coal Sector Restructuring Socialassessment 19703

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FÁK Állomáskódok

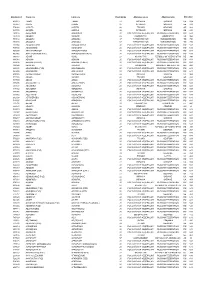

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

TULA М4 Rail М2 М2

CATALOGUE OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTS EXPORTED BY THE TULA REGION 1 CATALOGUE CONTENTS INFORMATION 3 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 6 METALLURGICAL INDUSTRY 16 CHEMICAL INDUSTRY 25 LIGHT INDUSTRY 36 FOOD INDUSTRY 48 CONTACT INFORMATION 62 2 CATALOGUE CONTENTS “THE FOREIGN TRADE TURNOVER STRUCTURE NOW MEETS ALL THE CRITERIA FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND IS EXPORT-ORIENTED. WE NEED TO INCREASE THE VOLUME OF EXPORTS AND FIND NEW SALES MARKETS.” Governor of the Tula Region Alexei Dyumin 3 TULA REGION TRADE WITH MAJOR TRADING PARTNERS: 126 USA, CHINA, COUNTRIES BELARUS, ALGERIA, TURKEY, UAE, GERMANY 36,2% Chemical industry products and rubber 28,1% Other goods 6,8% Mechanical engineering products 5% Foods and raw materials Population Total area Tula Novomoskovsk 23,9% Metals and metal 1 466 127 25 700 550,8 125,2 products people sq. km thousand people thousand people EXPORT STRUCTURE EXPORT 4 TULA REGION MOSCOW М2 MOSCOW REGION TWO FEDERAL HIGHWAYS • M2 ‘Crimea’ М4 Zaokskiy Rail • M4 ‘Don’ KALUGA REGION Aleksin RAILWAY ROUTES Yasnogorsk • MOSCOW–KHARKOV–SIMFEROPOL, Venoyv • MOSCOW–DONBAS; TULA TRANSPORT ROUTES Dubna Suvorov Novomoskovsk RYAZAN REGION • Tula – M4 ‘Don’ Transcaucasia, Western Asia (part of the Chekalin Shchyokino Uzlovaya Kimovsk European route E 115) Odoyev Kireyevsk • Tula – M2 ‘Crimea’ Europe (part of the European route E105) Belyov Arsenyevo Bogoroditsk Plavsk Tyoploye Volovo AIR TRAFFIC: • Sheremetyevo (210 km) – more than 230 domestic and М2 Chern Kurkino international destinations • Domodedovo (170 km) – 194 destinations Arkhangelskoye LIPETSK • Vnukovo (180 km) – more than 200,000 domestic and REGION international destinations ORYOL REGION Yefremov • Kaluga Airport (110 km) – 9 domestic destinations М4 5 MECHANICAL ENGINEERING THE TULAMASHZAVOD PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION The TULAMASHZAVOD Production Association is a major holding that includes the parent TULAMASHZAVOD Joint-Stock Company and twenty subsidiaries that focus equally on both the manufacturing of products for the defence industry and civilian products. -

ANNEX J Exposures and Effects of the Chernobyl Accident

ANNEX J Exposures and effects of the Chernobyl accident CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION.................................................. 453 I. PHYSICALCONSEQUENCESOFTHEACCIDENT................... 454 A. THEACCIDENT........................................... 454 B. RELEASEOFRADIONUCLIDES ............................. 456 1. Estimation of radionuclide amounts released .................. 456 2. Physical and chemical properties of the radioactivematerialsreleased ............................. 457 C. GROUNDCONTAMINATION................................ 458 1. AreasoftheformerSovietUnion........................... 458 2. Remainderofnorthernandsouthernhemisphere............... 465 D. ENVIRONMENTAL BEHAVIOUR OF DEPOSITEDRADIONUCLIDES .............................. 465 1. Terrestrialenvironment.................................. 465 2. Aquaticenvironment.................................... 466 E. SUMMARY............................................... 466 II. RADIATIONDOSESTOEXPOSEDPOPULATIONGROUPS ........... 467 A. WORKERS INVOLVED IN THE ACCIDENT .................... 468 1. Emergencyworkers..................................... 468 2. Recoveryoperationworkers............................... 469 B. EVACUATEDPERSONS.................................... 472 1. Dosesfromexternalexposure ............................. 473 2. Dosesfrominternalexposure.............................. 474 3. Residualandavertedcollectivedoses........................ 474 C. INHABITANTS OF CONTAMINATED AREAS OFTHEFORMERSOVIETUNION............................ 475 1. Dosesfromexternalexposure -

ECONOMIC CONDITIONS in RUSSIA 1 Catastrophic Change in the National Economy

C. 705. M. 451. 1922. II. LEAGUE OF NATIONS REPORT ON ECONOMIC CONDITIONS IN RUSSIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FAMINE OF 1921-1922 AND THE STATE OF AGRICULTURE CONTENTS Page Introductory N o t e on S o u r c e s of In f o r m a t io n ........................................................................................ v Chapter I. —- S u m m a r y of t h e S it u a t io n .................................................................................................. I Chapter II. —- R u ssia n A g r ic u l t u r e b e f o r e t h e F a m i n e ......................................................... 6 Chapter III. — T h e F a m in e o f 1921-1922........................................................................................................ 26 Chapter IV. — T h e P r e s e n t P o s i t i o n .............................................................................................................. 58 Annex I. ■— (a) The Russian Land System and the Agrarian Policy of the Soviet Govern ment ............................................................................................................................................................ 77 (b) The Single Food Tax ............................................................................................................. 88 Annex II. •— Recent Harvest Statistics..................................................................................................................... 93 Annex III. ■— Mr. Hoover's Report to President Harding on the Work of the American -

TULA REGION TULA Moscow Moscow REGION Region

TULA REGION TULA Moscow Moscow REGION region Kaluga region Tula Novomoskovsk Ryazan region Lipetsk Oryol region region Population Total area Tula Novomoskovsk 1.5million 25 700km2 550 800 125 200 OVERVIEW OF TULA REGION ECONOMY GRP Manufacturing (rating 2017) 40,5% 562 bn rubles industries 104,4% Wholesale and retail trade 12,2% Industrial production GRP structure growth 106,2% Transport and (2017) communications 6,5% Agricultural output Real estate transactions 11,4% production growth 110,4% (2017) Agriculture 7,0% Investment at current prices (2017) 127 bn rubles Other kinds of economic 22,4% activities 109,4% at comparable prices to 2016 FORMULA FOR SUCCESS Favorable Tailor-made Tax logistics approach benefits Highly qualified workforce Good governance FAVORABLE LOGISTICS Nearest airports: Domodedovo - 2hours km 180 Vnukovo - 2hours from Moscow Kaluga - 1hour and 40minutes In direct proximity to the largest target market М2 Crimea M4 Don Moscow Railway: southern branch of the Paveletsky route Major national highways INVESTOR INDIVIDUAL ACCOMPONIMENT Support in establishing local production Location matching Legal support State support at both the federal Selection of contractors and regional levels Regional integrated development projects Consulting support Establishment and development of industrial parks PPP projects One-stop shop 24/7 TAX BENEFITS Property tax reduction 0% up to 10 tax periods Income tax reduction 15,5% Projects from 100m rubles According to Tula region law No. 1390-ATR dated 06.02.2010 Investments in construction -

International Out-Of-Delivery-Area and Out-Of-Pickup-Area Surcharges

INTERNATIONAL OUT-OF-DELIVERY-AREA AND OUT-OF-PICKUP-AREA SURCHARGES International shipments (subject to service availability) delivered to or picked up from remote and less-accessible locations are assessed an out-of-delivery area or out-of-pickup-area surcharge. Refer to local service guides for surcharge amounts. The following is a list of postal codes and cities where these surcharges apply. Effective: January 17, 2011 Albania Crespo Pinamar 0845-0847 3254 3612 4380-4385 Berat Daireaux Puan 0850 3260 3614 4387-4388 Durres Diamante Puerto Santa Cruz 0852-0854 3264-3274 3616-3618 4390 Elbasan Dolores Puerto Tirol 0860-0862 3276-3282 3620-3624 4400-4407 Fier Dorrego Quequen 0870 3284 3629-3630 4410-4413 Kavaje El Bolson Rawson 0872 3286-3287 3633-3641 4415-4428 Kruje El Durazno Reconquista 0880 3289 3644 4454-4455 Kucove El Trebol Retiro San Pablo 0885-0886 3292-3294 3646-3647 4461-4462 Lac Embalse Rincon De Los Sauces 0909 3300-3305 3649 4465 Lezha Emilio Lamarca Rio Ceballos 2312 3309-3312 3666 4467-4468 Lushnje Esquel Rio Grande 2327-2329 3314-3315 3669-3670 4470-4472 Shkodra Fair Rio Segundo 2331 3317-3319 3672-3673 4474-4475 Vlore Famailla Rio Tala 2333-2347 3323-3325 3675 4477-4482 Firmat Rojas 2350-2360 3351 3677-3678 4486-4494 Andorra* Florentino Ameghino Rosario De Lerma 2365 3360-3361 3682-3683 4496-4498 Andorra Franck Rufino 2369-2372 3371 3685 4568-4569 Andorra La Vella General Alvarado Russel 2379-2382 3373 3687-3688 4571 El Serrat General Belgrano Salina De Piedra 2385-2388 3375 3690-3691 4580-4581 Encamp General Galarza -

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 010002 ПЕТРОЗАВОДСК PETROZAVODSK 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010214 ГОЛИКОВКА GOLIKOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010318 ШУЙСКИЙ МОСТ SHUISKII MOST 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010322 ТОМИЦЫ TOMICE 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010407 ШУЙСКАЯ SHUISKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010411 ОСТ. ПУНКТ 427 КМ OST. PUNKT 427 KM 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010426 ЛУЧЕВОЙ LUCHEVOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010500 СУНА SUNA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010515 ОСТ. ПУНКТ 437 КМ OST. PUNKT 437 KM 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010604 ЗАДЕЛЬЕ (РЗД) ZADELE 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010708 КОНДОПОГА KONDOPOGA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010727 МЯНСЕЛЬГА MIANSELGA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010731 ИЛЕМСЕЛЬГА ILEMSELGA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010801 КЕДРОЗЕРО KEDROZERO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010820 ЛИЖМА LIJMA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010835 НОВЫЙ ПОСЕЛОК NOVEI POSELOK 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010843 ВИКШЕЗЕРО VIKSHEZERO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 010905 НИГОЗЕРО NIGOZERO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 011005 КЯППЕСЕЛЬГА KIAPPESELGA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION -

Uzlovaya Kimovsk Kireyevsk Belyov

WHERE RUSSIAN INGENUITY LIVES TULA REGION INVESTMENT STRATEGY FOR 2019-2022 TULA REGION INVESTMENT STRATEGY. STRUCTURE Zаoksky Aleksin Yasnogorsk Leninsky Venyov CURRENT BACKGROUND AND DEVELOPMENT AND TULA STATUS TRENDS DETERMINING INVESTMENT PRIORITIES Suvorov Dubna THE STRATEGY Novomoskovsk Odoyev Shchyokino Uzlovaya Kimovsk Kireyevsk Belyov Arsenyevo Bogoroditsk Plavsk Tyoploye Volovo Kurkino Chern FINANCIAL AND N TOOLS. CENTRES OF Arkhangelskoye ON-FINANCIAL GOALS RESPONSIBILITY Yefremov STRATEGIC PLANNING DOCUMENTS. TULA REGION INVESTMENT STRATEGY THROUGH 2030 TULA REGION GOVERNMENT DECREE NO. 1113-Р DATED 11 DECEMBER 2013 STRATEGIC PRIORITIES AND TRENDS OF THE TULA REGION’S INVESTMENT DEVELOPMENT BY SECTOR: BY TERRITORY: INNOVATIVE RENEWAL OF TRADITIONAL ECONOMIC SECTORSИ TULA AGGLOMERATION DEVELOPMENT FORMATION OF A "NEW ECONOMY" CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT OF TERRITORIES INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS FOR REDUCING THE ANTHROPOGENIC IMPACT KEY DEVELOPMENT AREAS 1 IMPLEMENTING INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS 5 DEVELOPMENT OF THE TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE COMPREHENSIVE UPGRADING OF THE HOUSING AND UTILITIES COMPLEX, CREATION OF THE INVESTMENT INFRASTRUCTURE, SUCH AS INDUSTRIAL 2 6 LARGE-SCALE HOUSING CONSTRUCTION FOR LOW AND MEDIUM INCOME PARKS AND TECHNOPARKS, BUSINESS INCUBATORS POPULATION GROUPS DEVELOPMENT OF PRIORITY INVESTMENT AREAS BASED ON THE 3 LIFTING ELECTRICITY GRID RESTRICTIONS TO MEET CURRENT AND FUTURE 7 ESTABLISHED POTENTIAL OF BASIC INDUSTRIES CONSUMER NEEDS 4 CONSTRUCTION OF THE REQUISITE GAS TRANSPORTATION INFRASTRUCTURE TO -

Download Presentation

PRIORITY DEVELOPMENT AREA «ALEKSIN» («ALEKSIN» PDA) Priority Development Area «Aleksin» is established in accordance with the Decree of the RF Goverment of 12.04.2019 №430 ALEKSIN CITY DISTRICT GENERAL INFORMATION MOSCOW MOSCOW ADMINISTRATIVE CENTER ALEKSIN REGION ALEKSIN Zаoksky М6 М2 М4 KALYGA Yasnogorsk REGION TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE Leninsky Venyov RYAZAN REGION CITY ROAD «CRIMEA» - 31 KM FROM ALEKSIN Suvorov Dubna TULA Novomoskovsk Odoyev Shchyokino Uzlovaya Kimovsk Kireyevsk DISTANCE TO MAJOR CITIES Belyov Arsenyevo Bogoroditsk Plavsk TULA KALUGA MOSCOW Tyoploye Volovo LIPETSK 70 КМ 60 КМ 180 КМ REGION Kurkino Chern RAILWAY MOTOR ROADS OF REGIONAL Arkhangelskoye LINE IMPORTANCE «KALUGA-TULA» «TULA - ALEKSIN», «ALEKSIN - ZAOKSKY» ORYOL Yefremov «ZHELEZNYA - ALEKSIN», «ALEKSIN - PETRISHCHEVO» REGION «ALEKSIN - PERSHINO» ALEKSIN CITY DISTRICT ECONOMY POPULATION MANUFACTURE OF MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENT 38% 67 288 PEOPLE URBAN POPULATION - 57 950 PEOPLE OTHER NON-METALLIC RURAL POPULATION - 9 338 PEOPLE MINERAL PRODUCTS 18% TRADE, SERVICES 16% NUMBER OF WORKING AGE PERSONS ENERGY INDUSTRY 9% 35 110 PEOPLE CHEMICAL PRODUCTION 8% SECTORAL STRUCTURE OF THE «ALEKSIN» PDA OF AVERAGE MONTHLY CARDBOARD 7% SALARY (2018) PRODUCTION 30 015 RUBLES OTHER 7% ALEKSIN CITY DISTRICT LARGEST COMPANIES Research and Production Association «Tyazhpromarmatura» is a core machinery manufacturing enterprise of the city, which specializes in design Zаoksky and production of lock and pipeline valves for gas industry, petroleum industry, chemical industry and power industry. High quality of manufacturing products, progressive design and technological decisions allow company to hold leading positions in a field of pipeline valves production for years. The new production unit were launched in 2015 – that was a Sukhodolsky plant of special heavy machine building, which is focused on pipeline valve billets production using the Aleksin latest technologies. -

Tula Region Investment Potential General Information ТTULAУЛЬС REGIONКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ

TULA REGION GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION OF TULA REGION Tula Region investment potential General information ТTULAУЛЬС REGIONКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ The major highways and the main Population of the region - more than 1,5 million people Moscow railway lines of the Russian Federation Tula agglomeration - the largest in the Central Federal District 1,5 hours extend through the region. 1100 thousand people Moscow region • Area - 25 700 km2 Zaoksky • Climate - moderately continental Largest cities: Aleksin Yasnogorsk • Tula - more than 552 thousand people Kaluga region Venev • Novomoskovsk - more than 138 thousand people Leninsky Tula Highways: • М2 "Crimea", М4 "Don", Dubna Suvorov Novomoskovsk Ryazan region P132 "Kaluga - Ryazan", Shchekino Uzlovaya P140 "Tula - Novomoskovsk" Kimovsk Railways: Odoev Kireevsk • Moscow - Kharkiv - Simferopol Belev Bogoroditsk Arsenievo Plavsk • Moscow - Donbass Teploe Airports: Volovo • Domodedovo - 170 km Kurkino • Vnukovo - 180 km Chern • Sheremetyevo - 210 km Arkhangelskoye Lipetsk region 6 powergas generating main pipelines units Orel region Yefremov 7 cross-country pipelines Elements of the congenial investment climate ТTULAУЛЬС REGIONКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ Effective Industrialized Team Professional economy personnel Well-developed infrastructure Advantageous logistics Preferences Innovation potential Comfortable environment Economy ТTULAУЛЬС REGIONКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ Industrial structure Gross Regional Product 24,5% Machine-building in current prices (2016, estimated) 496 billion rubles 17,1% Chemical production 102,5% Food -

Тульская Область. Инвестиционный Паспорт Tula Region. Investment

Тульская область. Tula Region. Инвестиционный паспорт Investment Passport Инвестиционная деятельность Investments Внешне-экономическая деятельность Foreign economic activity Показатели экономического развития Indicators of economic development Промышленность Industry Сельское хозяйство Agriculture Инфраструктура Infrastructure Образование и наука Education and Science Здравоохранение Health service Туризм Tourism Потребительский рынок Consumer market Минерально-сырьевые ресурсы Mineral resources Основные тарифы Main tariff s Заокский Ясногорск Алексин Венев Ленинский Тула Дубна Суворов Новомосковск Щекино Одоев Кимовск Узловая Белев Донской Киреевск Арсеньево Богородицк Плавск Теплое Куркино Чернь Волово Архангельское Ефремов 2011 Краткая характеристика Тульской области Географическое положение ульская область расположена в центре Ев- ропейской части России на Среднерусской Твозвышенности в пределах степной и лесо- степной зон. Граничит на севере и северо-восто- ке — с Московской, на востоке — с Рязанской, на юго-востоке и юге — с Липецкой, на юге и юго- западе — с Орловской, на западе и северо-запа- де — с Калужской областями. Занимает площадь 25,7 тыс. кв. км (0,15% территории России). Наибольшая протяженность территории области с севера на юг — 200 км, с запада на восток — 190 км. Область располагает развитой транспортной се- тью, по которой осуществляются грузовые и пас- сажирские перевозки. Территорию области пере- секают важные стратегические автомобильные магистрали федерального значения: Москва– Крым, Москва–Дон, Калуга–Тула–Михайлов–Ря- -

Plan for Attracting Investment in the Economy of the Tula Region Tula Investment Development Indicators Region

PLAN FOR ATTRACTING INVESTMENT IN THE ECONOMY OF THE TULA REGION TULA INVESTMENT DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS REGION ТО ВВП THE PROPORTION OF FIXED INVESTMENT IN GRP (GDP), % ЦФО ВВП INVESTMENTS IN FIXED ASSETS, BN, RUB РФ 27 26,2 25,8 26 170,4 23,2 23,1 154,8 22,1 21,7 20,7 22 128,6 105,6 112,6 18 95,2 17 84,1 91,0 ВВП ВВП 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 ВРП GROSS REGIONAL PRODUCT, BN, RUB ВРП INDUSTRY STRUCTURE OF GROSS VALUE ADDED, % INDUSTRY 654,7 TRADE 600,94 AGRICULTURE 555,94 TRANSPORTATION AND STORAGE 518,69 477,54 BUILDING 411,12 OTHER 311,24 348,03 Manufacturing industry structure CHEMICAL INDUSTRY METALLURGICAL PRODUCTION ENGINEERING FOOD PRODUCTION PRODUCTS OF FABRICATED METAL PRODUCTS OTHERS 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 TULA ATTRACTED INVESTMENTS ? REGION 1 POSSIBLE INVESTMENT ORGANIC SYNTHESIS PRODUCTS AREAS MACHINE TOOL INDUSTRY, INDUSTRIAL MACHINERY, 20 2 CAR-PARTS PRODUCTION 3 СOMPOSITE MATERIALS 4 BIOTECHNOLOGIES, DEEP PROCESSING OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS ANALYSIS OF A POTENTIAL VALUE CREATION 5 AGRO-INDUSTRY AND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT 10 6 EXTRACTION AND PROCESSING OF RAW MATERIALS 7 TOURISM AND RECREATION INDUSTRY: CONSTRUCTION OF HOTELS CONTRIBUTION ANALYSIS OF THE PLAN FOR AND CAMPSITES, RECONSTRUCTION OF SANATORIUMS ATTRACTING INVESTMENT IN THE 8 REGIONAL ECONOMY 8 LOGISTICS (STORAGE AND TERMINAL SERVICES) 8 STRATEGIC PLAN GENERAL INVESTMENT PRIORITIES TULA STATE SUPPORT MEASURES REGION State support measures Category of recipients of