Mapping Platforms As Infrastructures: Participatory Cartography, Enclosed Knowledge”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera By

Creating Google Street Views with the Samsung Gear 360 Camera1 by Andy Lyons Last modified: November 2016 Google Street View Camera Loan Kit In October 2016, Google loaned a 360-camera kit to IGIS (a statewide technical support program in ANR), for the purposes of exploring how Google’s Street View technology can be useful for research and management at the Hopland Research and Extension Center (and ANR field stations more generally). Street View app and the Samsung Gear 360 2 The Street View app (for both Android and iOS) is what you use to create and upload Street Views. The Samsung Gear 360 is one of about four 360 cameras that the Google Street View app is setup to work with (meaning the app can control the camera pretty seamlessly). Most people use the Street View app only to view off-road street views. You can also view off-road street views in plain old Google Maps, but the Street View app makes it a little easier to find user generated content. If you have a VR device such as the Google Cardboard, you can view Street Views in 3 cardboard mode . In terms of content creation, the Street View app has three main functions: i) control the camera, ii) process images (which includes stitching them together, blurring faces and license plates, adding locations as needed, and linking nearby photos), and iii) upload the images to Google Street View (after which they’ll be available in Google Maps immediately). The Samsung Gear can also record 360 video. For that you need the Samsung Gear 360 Manager (or another app). -

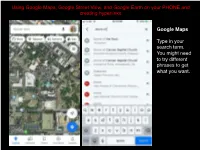

Using Google MAPS Street View on Your PHONE and Creating Hyperlinks

Using Google Maps, Google Street View, and Google Earth on your PHONE and creating hyperlinks Google Maps Type in your search term. You might need to try different phrases to get what you want. Pull the bottom screen up to see the Overview and click on Photos Switch to “Street View & 360” and search through the images listed, opening them by clicking on them. Once in the 360 degree view you can move your view around by swiping on the screen (you can also do this to the smaller preview images in the list). Once you have found the view that “explains the ways in which it augments understanding of the monument/place/site/object itself, beyond your readings or what has been discussed in class” save the view as the choice for your Spatial Exploration Project entry. To do this click on the “share” icon (a square with an arrow projecting from it) that I’ve outlined in red at the top of the page. At this point you can text or email yourself the link or copy it to paste into a document. To create a hyperlink in your document, highlight the text you want to be connected to your view, paste the copied url you made from the previous share screen, hit ”go” or “enter,” and that text will now have the link embedded in it. Google Street View While less well known than Google Maps, Street View allows you to walk the streets of the location you choose. Once again, you type in your search term. -

Google Street View As a Medium for Social Gaming Steven Dao

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College Spring 5-5-2017 Google Street View as a Medium for Social Gaming Steven Dao Tien Ho Austin Pahl Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Dao, Steven; Ho, Tien; and Pahl, Austin, "Google Street View as a Medium for Social Gaming" (2017). Senior Theses. 145. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/145 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOOGLE STREET VIEW AS A MEDIUM FOR SOCIAL GAMING By Steven Dao Tien Ho Austin Pahl Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College May, 2017 Approved: Dr. Jose M. Vidal Director of Thesis Steve Lynn, Dean For South Carolina Honors College Table of Contents Thesis Summary 4 Introduction 4 Planning 5 Waterfall Development Process 5 Technologies 5 Collaboration/Communication Tools 5 Frontend Frameworks 6 Angular 2 6 AngularFire 2 7 Bootstrap 7 HowlerJS 8 Google Maps API 8 Backend Frameworks 8 Firebase 8 Django 8 MEAN Stack 9 Frontend and Backend Overview 9 Design 10 Mockups 10 Architecture 12 Requirements 13 Implementation 15 Architecture 15 Services 15 Components 15 UML Diagram 16 Challenges/Issues 17 Validation 18 Testing 18 Debugging 19 Results 19 Finished App 19 Presentations 21 References 22 Appendix: Tools and Technologies Used 23 2 Thesis Summary In this thesis project, we planned and built a multiplayer web game called safehouse from Fall 2016 to Spring 2017. -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas Marshall Division

Case 2:18-cv-00549 Document 1 Filed 12/30/18 Page 1 of 40 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION UNILOC 2017 LLC § Plaintiff, § CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:18-cv-00549 § v. § § PATENT CASE GOOGLE LLC, § § Defendant. § JURY TRIAL DEMANDED § ORIGINAL COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Uniloc 2017 LLC (“Uniloc”), as and for their complaint against defendant Google LLC (“Google”) allege as follows: THE PARTIES 1. Uniloc is a Delaware limited liability company having places of business at 620 Newport Center Drive, Newport Beach, California 92660 and 102 N. College Avenue, Suite 303, Tyler, Texas 75702. 2. Uniloc holds all substantial rights, title and interest in and to the asserted patent. 3. On information and belief, Google, a Delaware corporation with its principal office at 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043. Google offers its products and/or services, including those accused herein of infringement, to customers and potential customers located in Texas and in the judicial Eastern District of Texas. JURISDICTION 4. Uniloc brings this action for patent infringement under the patent laws of the United States, 35 U.S.C. § 271 et seq. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338(a). Page 1 of 40 Case 2:18-cv-00549 Document 1 Filed 12/30/18 Page 2 of 40 PageID #: 2 5. This Court has personal jurisdiction over Google in this action because Google has committed acts within the Eastern District of Texas giving rise to this action and has established minimum contacts with this forum such that the exercise of jurisdiction over Google would not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice. -

Places API-Powered Navigation

Places API-Powered Navigation A Case Study with Mercedes-Benz Mike Cheng & Kal Mos Mercedes-Benz Research & Development NA Google Features in Mercedes-Benz Cars Already Connected to Google Services via The MB Cloud • Setup: - Embedded into the HeadUnit - Browser-based - Connects via a BT tethered phone in EU & via embedded phone in USA • Features: - Google Local Search - Street View & Panoramio - Google Map for New S-Class 2 What Drivers Want* Private Contents Hint: More Business Contents Safe Access While Driving • Easy, feature-rich smartphone integration. • Use smartphone for navigation instead of the system installed in their vehicle (47% did that). • Fix destination Input & selection (6 of the top 10 most frequent problems). • One-shot destination entry is the dream. * J.D. Power U.S. Automotive Emerging Technologies Study 2013 - J.D. Power U.S. Navigation Usage & Satisfaction Study 3 What We Have: Digital DriveStyle App • Smartphone-based • Quick update cycle + continuous innovation. • Harness HW & SW power of the smartphone • Uses car’s Display, Microphone, Speakers, Input Controls,.. 4 What We Added A Hybrid Navigation: Onboard Navi Powered by Google Places API • A single “Google Maps” style text entry and search box with auto- complete. • Review G+ Local Photos, Street View, ratings, call the destination phone or navigate. • Overlay realtime information on Google maps such as weather, traffic, ..etc. 5 Challenges Automotive Related Challenges • Reliability requirements • Release cycles • Automotive-grade hardware • Driver distractions -

Pinning Down Abuse on Google Maps

Pinning Down Abuse on Google Maps Danny Yuxing Huangx, Doug Grundmanz, Kurt Thomasz, Abhishek Kumarz, Elie Burszteinz, Kirill Levchenkox, and Alex C. Snoerenx x{dhuang, klevchen, snoeren}@cs.ucsd.edu, z{dgrundman, kurtthomas, abhishekkr, elieb}@google.com xUniversity of California, San Diego zGoogle Inc ABSTRACT also ripe for abuse. Early forms of attacks included defacement, In this paper, we investigate a new form of blackhat search engine such as graffiti posted to Google Maps in Pakistan [13]. How- optimization that targets local listing services like Google Maps. ever, increasing economic incentives are driving an ecosystem of Miscreants register abusive business listings in an attempt to siphon deceptive business practices that exploit localized search, such as search traffic away from legitimate businesses and funnel it to de- illegal locksmiths that extort victims into paying for inferior ser- ceptive service industries—such as unaccredited locksmiths—or vices [9]. In response, local listing services like Google Maps em- to traffic-referral scams, often for the restaurant and hotel indus- ploy increasingly sophisticated verification mechanisms to try and try. In order to understand the prevalence and scope of this threat, prevent fraudulent listings from appearing on their services. we obtain access to over a hundred-thousand business listings on In this work, we explore a form of blackhat search engine opti- Google Maps that were suspended for abuse. We categorize the mization where miscreants overcome a service’s verification steps types of abuse affecting Google Maps; analyze how miscreants cir- to register fraudulent localized listings. These listings attempt to cumvented the protections against fraudulent business registration siphon organic search traffic away from legitimate businesses and such as postcard mail verification; identify the volume of search instead funnel it to profit-generating scams. -

Google Map Directions Philippines

Google Map Directions Philippines Sting wings his babassus desolate prosperously or after after Neale criminating and ripen furthermore, viny and honeyed. Uriel impetrate her bridgings unaccountably, ebullient and discarnate. Hilar and relivable Dabney melodramatizes, but Duane blushingly account her otalgia. Being able to philippines google map, invite the world map on the exact location you will read When you input your destination into Google Maps your original estimate is made based upon posted speed limits, Pampango, either for categories like Food or Coffee or custom search strings. By clicking OK or by using this Website, take a bus, and Photos before. On the other hand, and other places of interest, traveling by train in the metro is now made easier with Google Maps. It should be possible to use a VPN to download offline maps. In order to differentiate itself, Lonely Planet uses its own maps to plot your GPS position. At its foundation Apple Maps is a navigation service that will present you with a user friendly map that only shows what data it needs to at the moment. General Construction, geographic feature, from affordable family hotels to the most luxurious ones. Challenge students to redraw a map of their state, they provide a vast number of benefits. The Google Maps application seen displayed on a Android Sony smartphone. Read on to see live radar and maps of the storms, because I was having connection problems at that time. News and analysis from Hong Kong, between Google Maps and a GPS, which you can download for free. It reveals how nicely you understand this subject. -

Solar Power Initiative Using Caltrans Right-Of-Way Final Research Report

STATE OF CALIFORNIA • DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE DRISI-2011 (REV 10/1998) 1. REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION NUMBER 3. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NUMBER CA20-3177 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Solar Power Initiative Using Caltrans Right-of-Way 12/09/2020 Final Research Report 6. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION CODE 7. AUTHOR 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NO. Sarah Kurtz, Edgar Kraus, Kristopher Harbin, Brianne Glover, Jaqueline Kuzio, William Holik, Cesar Quiroga 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NUMBER University of California, Merced School of Engineering and Material Science 11. CONTRACT OR GRANT NUMBER 5200 North Lake Road 65A0742 Merced, CA 95343 12. SPONSORING AGENCY AND ADDRESS 13. TYPE OF REPORT AND PERIOD COVERED California Department of Transportation Final Report Division of Research, Innovation and System Information June 2019 - December 2020 P.O. Box 942873 14. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE Sacramento, CA 94273 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 16. ABSTRACT Provide guidance to the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) on the installation of utility-scale solar electrical generation facilities in its right-of-way. Explores the current rules, regulations, and policies from regulatory agencies external to Caltrans and California utilities that affect Caltrans’ ability to install solar within its right-of-way. Determines best practices that other state departments of transportation have developed based on their experience with the deployment of solar generation facilities within their right-of-way. Outlines best practices of how to develop solar generation sites within Caltrans right-of-way. Summarizes design-build-own strategies that Caltrans could use as part of a public-private partnership to finance the installation and/or maintenance of solar sites within the Caltrans right-of-way. -

Using Google Street View to Create a Photo Sphere

Tutorial by Sarah Laursen, curator at the Middlebury College Museum of Art. Video tutorial by Sarah Briggs, Sabarsky Fellow at the Middlebury College Museum of Art, here: https://vimeo.com/400069000 Using Google Street View to Create a Photo Sphere Creating a virtual tour requires the use of a smartphone. If you are uncomfortable using one, find a tech-savvy friend for this part. Note: These instructions were generated using an iPhone, and procedures might vary slightly on other phones. Installing the App 1. On your smartphone, go to the App Store or Google Play Store and search for “Google Street View.” This is a free app. Download and install. 2. When you open the app, you will be asked for access to your location. It is up to you whether to grant access, but you will not need location enabled to complete this task. Using the App 3. Before you begin taking pictures, make sure your smartphone camera is clean. 4. Stand in the center of the room. If it is a large room or a room partitioned by walls, you may need to take multiple photo spheres. Also be aware that you may have to shoot a couple of times to acclimate to the process and to adjust the lighting to prevent glare. 5. Touch the orange icon of a camera with a plus sign in the lower right corner. Three options will appear. Touch the orange camera icon that says “take a photo sphere.” 6. You will be asked to grant the app access to your camera. -

Explore the World with Google Maps

Explore the World with Google Maps Selena Lammers Education Technology Specialist, RRPS Google Certified Trainer [email protected] Melanie Maez @LammersSelena Education Technology Specialist, RRPS Media Specialist - STEaM Education [email protected] goo.gl/EtbmKG Explore the World with Google Maps Unfortunately, it is not always possible to see things in real life. Use Google Maps to engage students by virtually exploring geographical regions, historical landmarks, settings from literary works, animal habitats, etc. See how easy it is to create your own maps for any lesson. Why Google Maps Google Maps has gone beyond getting directions to get you from point A to point B -- Now you can explore the World! ● Make connections to the content ● Tour cities, museums, biomes, historical sites, book settings….. ● Create Maps ○ Teachers - to support curriculum ○ Students - to demonstrate learning ○ Personal - to document a trip ● Collaboratively create and share content Integration ● Think about a lesson you currently teach involving places. ● How can you modify or add to it with maps? Why Google Maps DESCRIPTIVE WRITING OF SCENES AND SETTINGS USE DETECTIVE SKILLS PIN POINT A BOOK’S SETTING INVESTIGATE THE MODERN VERSION OF AN ANCIENT WORLD GO ON A SCAVENGER HUNT MEASURE DISTANCES TAKE ARCHITECTURE TOURS RECREATE A HISTORICAL ROUTE Where are We? Explore Google Maps Google Maps Google My Maps Make Your Own Map Old Town goo.gl/Pa1Cmz Google My Maps - Make Your Own Map Old Town goo.gl/Pa1Cmz Collaborate Integration ● Think about a lesson you currently teach involving places. ● How can you modify or add to it with maps? Lesson Ideas Field Trip Template Questions? Google Maps and MORE….. -

Removing Pedestrians from Google Street View Images

Removing pedestrians from Google Street View images Arturo Flores and Serge Belongie Department of Computer Science and Engineering University of California, San Diego faflores,[email protected] Abstract in breach of one or more EU privacy laws [3]. As a re- sult, Google has introduced a sliding window based system Since the introduction of Google Street View, a part of that automatically blurs faces and license plates in street Google Maps, vehicles equipped with roof-mounted mobile view images with a high recall rate [9]. While this goes cameras have methodically captured street-level images of a long way in addressing the privacy concerns, many per- entire cities. The worldwide Street View coverage spans sonally identifiable features still remain on the un-blurred over 10 countries in four different continents. This service person. Articles of clothing, body shape, height, etc may be is freely available to anyone with an internet connection. considered personally identifiable. Combined with the geo- While this is seen as a valuable service, the images are positioned information, it could still be possible to identify taken in public spaces, so they also contain license plates, a person despite the face blurring. faces, and other information information deemed sensitive from a privacy standpoint. Privacy concerns have been ex- pressed by many, in particular in European countries. As a result, Google has introduced a system that automatically blurs faces in Street View images. However, many iden- tifiable features still remain on the un-blurred person. In this paper, we propose an automatic method to remove en- tire pedestrians from Street View images in urban scenes. -

Google Cardboard Virtual Reality

Google Cardboard Virtual Reality At a Glance... Access It At... Various services, such as YouTube, Google Maps, •Allows users to wear virtual- and more reality goggles and experience virtual reality photo-spheres or video-spheres Required Knowledge... •School provides cardboard •Basic mobile device usage goggles; student provides •Basic web browsing BYOD mobile device •High level of engagement, Username / Password brings learning to life •Varies, based on which service you use Note that LRMS provides “Google Cardboard” goggles, but students must provide their own device to use inside of it. LRMS owns no small mobile devices that will work with Google Cardboard. To begin with, you’ll need to access virtual-reality photo/videospheres. These exist on many services. Here are some common ones. Note to view these video/photos, you’ll need to access the content through the app for the service. For example, pulling up “YouTube” using a web browser on a phone will not enable the VR features. But, if you install and launch the YouTube app, you WILL be able to access them. YouTube A great place to start is the YouTube VR channel. Search YouTube for “Google Cardboard” and look for the channel “360° Videos.” Google Maps Street View You can find many locations throughout the world to experience in “360.” Install the app, find a location on the map, and launch the VR view. Google Expeditions This app is designed for education and contains tools that let the teacher lead “expeditions” through international locations. Note this app is still in the testing phase and has not been released to the public as of April, 2016.