Primary Undifferentiated High-Grade Pleomorphic Sarcoma/Malignant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1

Case Report pISSN 1738-2637 / eISSN 2288-2928 J Korean Soc Radiol 2015;72(4):295-299 http://dx.doi.org/10.3348/jksr.2015.72.4.295 Bilateral Presentation of Pleural Desmoplastic Small Round Cell Tumors: A Case Report1 양측 흉막에 발생한 결합조직형성 소원형세포종양의 증례 보고1 You Sun Won, MD1, Jai Soung Park, MD1, Sun Hye Jeong, MD1, Sang Hyun Paik, MD1, Heon Lee, MD1, Jang Gyu Cha, MD1, Eun Suk Koh, MD2 Departments of 1Radiology, 2Pathology, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, Bucheon, Korea Desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT) is a highly aggressive malignant small cell neoplasm occurring mainly in the abdominal cavity, but it is extremely rare in Received October 13, 2014; Accepted December 21, the pleura. In this case, a 15-year-old male presented with a 1-month history of left 2014 chest pain. Chest radiographs revealed pleural thickening in the left hemithorax and Corresponding author: Jai Soung Park, MD Department of Radiology, Soonchunhyang University chest computed tomography showed multifocal pleural thickening with enhance- College of Medicine, Bucheon Hospital, 170 Jomaru-ro, ment in both hemithoraces. A needle biopsy of the left pleural lesion was performed Wonmi-gu, Bucheon 420-767, Korea. and the final diagnosis was DSRCT of the pleura. We report this unusual case aris- Tel. 82-32-621-5851 Fax. 82-32-621-5874 E-mail: [email protected] ing from the pleura bilaterally. The pleural involvement of this tumor supports the hypothesis that it typically occurs in mesothelial-lined surfaces. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) Index terms which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distri- Pleura bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the Thickened Pleura original work is properly cited. -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

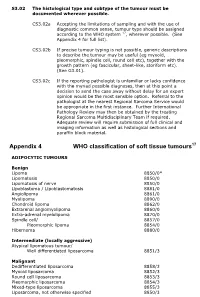

Appendix 4 WHO Classification of Soft Tissue Tumours17

S3.02 The histological type and subtype of the tumour must be documented wherever possible. CS3.02a Accepting the limitations of sampling and with the use of diagnostic common sense, tumour type should be assigned according to the WHO system 17, wherever possible. (See Appendix 4 for full list). CS3.02b If precise tumour typing is not possible, generic descriptions to describe the tumour may be useful (eg myxoid, pleomorphic, spindle cell, round cell etc), together with the growth pattern (eg fascicular, sheet-like, storiform etc). (See G3.01). CS3.02c If the reporting pathologist is unfamiliar or lacks confidence with the myriad possible diagnoses, then at this point a decision to send the case away without delay for an expert opinion would be the most sensible option. Referral to the pathologist at the nearest Regional Sarcoma Service would be appropriate in the first instance. Further International Pathology Review may then be obtained by the treating Regional Sarcoma Multidisciplinary Team if required. Adequate review will require submission of full clinical and imaging information as well as histological sections and paraffin block material. Appendix 4 WHO classification of soft tissue tumours17 ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS Benign Lipoma 8850/0* Lipomatosis 8850/0 Lipomatosis of nerve 8850/0 Lipoblastoma / Lipoblastomatosis 8881/0 Angiolipoma 8861/0 Myolipoma 8890/0 Chondroid lipoma 8862/0 Extrarenal angiomyolipoma 8860/0 Extra-adrenal myelolipoma 8870/0 Spindle cell/ 8857/0 Pleomorphic lipoma 8854/0 Hibernoma 8880/0 Intermediate (locally -

The Best Diagnosis Is

Dermatopathology Diagnosis Superficial Plantar Fibromatosis The best diagnosis is: H&E, original magnification 40. a. dermatofibroma b. keloid CUTISc. neurofibroma d. nodular fasciitis Do Note. superficialCopy plantar fibromatosis H&E, original magnification 400. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 225 FOR DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION Luke Lennox, BA; Anna Li, BS; Thomas N. Helm, MD Mr. Lennox and Dr. Helm are from the Department of Dermatology, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Ms. Li is from the Department of Dermatology, Ross University, Dominica, West Indies. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Thomas N. Helm, MD, Dermatopathology Laboratory, 6255 Sheridan Dr, Building B, Ste 208, Williamsville, NY 14221 ([email protected]). 220 CUTIS® WWW.CUTIS.COM Copyright Cutis 2013. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Dermatopathology Diagnosis Discussion Superficial Plantar Fibromatosis lantar fibromatosis typically presents as firm represents a reactive proliferation of spindle cells most plaques or nodules on the plantar surface of the often encountered on the extremities of young adults. Pfoot.1 The process is caused by a proliferation of Spindle cells are loosely arranged in a mucinous fibroblasts and collagen and has been associated with stroma and are not circumscribed (tissue culture ap- trauma, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, and pearance). Vesicular nuclei are encountered, but there alcoholism.2 Unlike the fibromatoses associated with is no remarkable nuclear pleomorphism. Extravasated Gardner syndrome, superficial plantar fibromatosis has not been associated with abnormalities in the ade- nomatous polyposis coli gene or with the -catenin gene.3,4 Lesions typically present in middle-aged or elderly individuals and involve the medial plantar fas- cia. -

About Soft Tissue Sarcoma Overview and Types

cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 About Soft Tissue Sarcoma Overview and Types If you've been diagnosed with soft tissue sarcoma or are worried about it, you likely have a lot of questions. Learning some basics is a good place to start. ● What Is a Soft Tissue Sarcoma? Research and Statistics See the latest estimates for new cases of soft tissue sarcoma and deaths in the US and what research is currently being done. ● Key Statistics for Soft Tissue Sarcomas ● What's New in Soft Tissue Sarcoma Research? What Is a Soft Tissue Sarcoma? Cancer starts when cells start to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer and can spread to other areas. To learn more about how cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?1 There are many types of soft tissue tumors, and not all of them are cancerous. Many benign tumors are found in soft tissues. The word benign means they're not cancer. These tumors can't spread to other parts of the body. Some soft tissue tumors behave 1 ____________________________________________________________________________________American Cancer Society cancer.org | 1.800.227.2345 in ways between a cancer and a non-cancer. These are called intermediate soft tissue tumors. When the word sarcoma is part of the name of a disease, it means the tumor is malignant (cancer).A sarcoma is a type of cancer that starts in tissues like bone or muscle. Bone and soft tissue sarcomas are the main types of sarcoma. Soft tissue sarcomas can develop in soft tissues like fat, muscle, nerves, fibrous tissues, blood vessels, or deep skin tissues. -

The Role of Cytogenetics and Molecular Diagnostics in the Diagnosis of Soft-Tissue Tumors Julia a Bridge

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, S80–S97 S80 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 The role of cytogenetics and molecular diagnostics in the diagnosis of soft-tissue tumors Julia A Bridge Department of Pathology and Microbiology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare, comprising o1% of all cancer diagnoses. Yet the diversity of histological subtypes is impressive with 4100 benign and malignant soft-tissue tumor entities defined. Not infrequently, these neoplasms exhibit overlapping clinicopathologic features posing significant challenges in rendering a definitive diagnosis and optimal therapy. Advances in cytogenetic and molecular science have led to the discovery of genetic events in soft- tissue tumors that have not only enriched our understanding of the underlying biology of these neoplasms but have also proven to be powerful diagnostic adjuncts and/or indicators of molecular targeted therapy. In particular, many soft-tissue tumors are characterized by recurrent chromosomal rearrangements that produce specific gene fusions. For pathologists, identification of these fusions as well as other characteristic mutational alterations aids in precise subclassification. This review will address known recurrent or tumor-specific genetic events in soft-tissue tumors and discuss the molecular approaches commonly used in clinical practice to identify them. Emphasis is placed on the role of molecular pathology in the management of soft-tissue tumors. Familiarity with these genetic events -

Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone

bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 3 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours WHO OMS International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Edited by Christopher D.M. Fletcher K. Krishnan Unni Fredrik Mertens IARCPress Lyon, 2002 bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 4 World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Series Editors Paul Kleihues, M.D. Leslie H. Sobin, M.D. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone Editors Christopher D.M. Fletcher, M.D. K. Krishnan Unni, M.D. Fredrik Mertens, M.D. Coordinating Editor Wojciech Biernat, M.D. Layout Lauren A. Hunter Illustrations Lauren A. Hunter Georges Mollon Printed by LIPS 69009 Lyon, France Publisher IARCPress International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) 69008 Lyon, France bb5_1.qxd 13.9.2006 14:05 Page 5 This volume was produced in collaboration with the International Academy of Pathology (IAP) The WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone presented in this book reflects the views of a Working Group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference in Lyon, France, April 24-28, 2002. Members of the Working Group are indicated in the List of Contributors on page 369. bb5_1.qxd 22.9.2006 9:03 Page 6 Published by IARC Press, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 150 cours Albert Thomas, F-69008 Lyon, France © International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2002, reprinted 2006 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accordance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. -

Practical Issues for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Vicky Pham, MS, Evita Henderson-Jackson, MD, Matthew P

Pathology Report Practical Issues for Retroperitoneal Sarcoma Vicky Pham, MS, Evita Henderson-Jackson, MD, Matthew P. Doepker, MD, Jamie T. Caracciolo, MD, Ricardo J. Gonzalez, MD, Mihaela Druta, MD, Yi Ding, MD, and Marilyn M. Bui, MD, PhD Background: Retroperitoneal sarcoma is rare. Using initial specimens on biopsy, a definitive diagnosis of histological subtypes is ideal but not always achievable. Methods: A retrospective institutional review was performed for all cases of adult retroperitoneal sarcoma from 1996 to 2015. A review of the literature was also performed related to the distribution of retroperitoneal sarcoma subtypes. A meta-analysis was performed. Results: Liposarcoma is the most common subtype (45%), followed by leiomyosarcoma (21%), not otherwise specified (8%), and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (6%) by literature review. Data from Moffitt Cancer Center demonstrate the same general distribution for subtypes of retroperitoneal sarcoma. A pathology-based algorithm for the diagnosis of retroperitoneal sarcoma is illustrated, and common pitfalls in the pathology of retroperitoneal sarcoma are discussed. Conclusions: An informative diagnosis of retroperitoneal sarcoma via specimens on biopsy is achievable and meaningful to guide effective therapy. A practical and multidisciplinary algorithm focused on the histopathology is helpful for the management of retroperitoneal sarcoma. Introduction tic, and predictive information based on a relatively Soft-tissue sarcomas are mesenchymal neoplasms small amount of tissue obtained -

Aggressive Fibromatosis of the Chest Wall Mimicking Low Grade Fibrosarcoma - an Unusual Clinical Presentation

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571 Case Report Aggressive Fibromatosis of the Chest Wall Mimicking Low Grade Fibrosarcoma - An Unusual Clinical Presentation Dr. Nimisha Sharma1*, Dr. Sumanashree Mallappa2**, Dr. Sujata Raychaudhuri3*, Dr Amit Yadav3**, Prof. Dr. A. K. Mandal4** 1Assistant Professor, 2Senior Resident, 3Associate Professor, 4Director Professor, *Dept. of Pathology, ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Faridabad **Dept. of Pathology, VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi Corresponding Author: Dr. Nimisha Sharma ABSTRACT Background: Aggressive fibromatosis (AF), also known as desmoid tumour or musculoaponeurotic fibromatosis is a monoclonal fibroblastic proliferative disease. It can present as abdominal and extra- abdominal fibromatosis. Extra abdominal deep fibromatosis represent 3.5% of fibrous tissue tumor and 0.03% of all neoplasms. Anterior chest wall forms 10% of Extra abdominal deep fibromatosis cases. Case history: Patient presented with a progressively increasing large swelling on the chest wall since 2 years. On examination, firm to hard ill defined growth was found. Microscopic examination showed a cellular spindle cell tumour. Strong positivity for VIMENTIN and focal positivity for SMA and DESMIN was seen on Immunohistochemistry. Final Diagnosis of aggressive fibromatosis was made. Conclusion: This case is being presented for its rarity, unusual clinical presentation and overlapping clinical and histopathological features with fibrosarcoma, which is a malignant -

Synovial Sarcoma- an Unusual Cause of Heel Pain

Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 2008 Vol 2 No 2 MY Norhamdan, et al Synovial Sarcoma- An unusual cause of Heel Pain MY Norhamdan, MS (Ortho), Y Shahril, MS (Ortho), O Masbah, MS (Ortho), Siti Aishah MA*, MIAC Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, UKM Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia * Department of Pathology, UKM Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia ABSTRACT imaging revealed a well-circumscribed heterogeneous lesion, isointense to muscle on T(1)-weighted image and We report a case of 29-year-old female who presented with hyperintense on T(2) image indicating a benign lesion right heel pain that worsened over a period of two years. The (Figure 2). Due to close proximity to the posterior tibial onset of pain was followed by swelling at the medial aspect nerve, the patient was diagnosed with neuroma. of right ankle. She was initially treated for plantar fasciitis with multiple steroid injections over the heel. Subsequent The patient underwent excision biopsy and intra-operatively MRI revealed a well-defined heterogeneous lesion in the lesion was noted to be a soft, friable mass encasing the continuity with the medial plantar nerve. Excision biopsy medial plantar nerve (Figure 3). Histopathological was performed and histopathological evaluation revealed evaluation revealed monophasic synovial sarcoma as monophasic synovial sarcoma. The patient subsequently evidenced by spindle-shaped and neoplastic cells. underwent wide resection and free tissue transfer followed by Imunohistochemically the neoplastic cells were positive for radiotherapy and chemotherapy. This case highlights an vimentin and focally positive for EMA, CK, and CD 99 but unusual site and presentation of synovial sarcoma which led negative for CD 34, CD 31, desmin, myoglobin, smooth to delayed diagnosis and treatment. -

High-Grade Soft Tissue Sarcoma Arising in a Desmoid Tumor

Bertucci et al. Clin Sarcoma Res (2015) 5:25 DOI 10.1186/s13569-015-0040-0 Clinical Sarcoma Research CASE REPORT Open Access High‑grade soft tissue sarcoma arising in a desmoid tumor: case report and review of the literature François Bertucci1,2*, Marjorie Faure1, Maria‑Rosa Ghigna3, Bruno Chetaille4, Jérôme Guiramand5, Laurence Moureau‑Zabotto6, Anthony Sarran7 and Delphine Perrot1 Abstract Desmoid tumors are rare benign monoclonal fibroblastic tumors. Their aggressiveness is local with no potential for metastasis or dedifferentiation. Here we report on a 61-year-old patient who presented a locally advanced breast desmoid tumor diagnosed 20 years after post-operative radiotherapy for breast carcinoma. After 2 years of medical treatment, a high-grade undifferentiated pleomorphic soft tissue sarcoma arose within the desmoid tumor. Despite extensive surgery removing both tumors, the patient showed locoregional relapse by the sarcoma, followed by multimetastatic progression, then death 25 months after the surgery. The arising of a soft tissue sarcoma in a desmoid tumor is an exceptional event since our case is the fourth one reported so far in literature. It reinforces the need for timely and accurate diagnosis when a new mass develops in the region of a preexisting desmoid tumor, and more generally when a desmoid tumor modifies its clinical or radiological aspect. Keywords: Breast cancer, Desmoid tumor, Soft tissue sarcoma Background classification of sarcomas, they are classified as tumors Desmoid tumors (DT) are rare benign monoclonal fibro- with intermediate malignancy potential. Locally, they can blastic tumors representing less than 5 % of all soft tissue damage vital structures and threaten life [7], notably in tumors [1]. -

Clinicopathological Features of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans

ONCOLOGY LETTERS 11: 661-667, 2016 Clinicopathological features of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans NOPPADOL LARBCHAROENSUB1, JITCHAI KAYANKARNNAVEE1, SUDA SANPAPHANT1, KIDAKORN KIRANANTAWAT2, CHEWARAT WIROJTANANUGOON3 and VORACHAI SIRIKULCHAYANONTA1 Departments of 1Pathology, 2Surgery and 3Radiology, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10400, Thailand Received November 8, 2014; Accepted August 25, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2015.3966 Abstract. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is Introduction a superficial cutaneous tumor of low malignant potential characterized by a high rate of local recurrence. The histo- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a superficial, pathological appearance shows uniform spindle neoplastic low‑grade, locally aggressive, spindle, fibroblastic, neoplastic cells arranged in a predominantly storiform pattern, typically lesion. As a relatively uncommon neoplasm and locally with positive staining for cluster of differentiation (CD)34 aggressive cutaneous tumor, it is characterized by high and vimentin on immunohistochemistry. A minority of cases rates of local recurrence, but a low risk of metastasis (1-4). of DFSP have areas of sarcomatous transformation. Wide DFSP typically presents with a purple or pink asymptom- surgical excision is the cornerstone of treatment for DFSP. atic plaque or nodule, with a history of slow but persistent The objective of the present study was to determine the clini- growth (1). DFSPs usually affect young to middle-aged adult copathological features of DFSP. Pathological records were patients (1-4). The tumor was first described in 1924 by searched for cases of DFSP in the database of the Department Darier and Ferrand as a ‘progressive and recurring dermatofi- of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital broma’, which is a nodular cutaneous tumor characterized by (Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand) between 1994 and a prominent storiform pattern (5).