Visibility of Invisible Africans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31 Churches to Close Grace to the Catholic Church

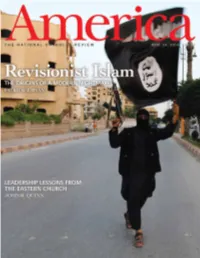

OF MANY THINGS n one long wall of my office Accordingly, Father Hunt soon returned 106 West 56th Street in New York, arranged in to his duties as literary editor. In New York, NY 10019-3803 Ph: 212-581-4640; Fax: 212-399-3596 1984 he was named editor in chief. Otwo rows, are the portraits Subscriptions: 1-800-627-9533 of of my predecessors, 13 in all since In 1987 he was among 16 Catholic www.americamagazine.org 1909. Among them are some of the journalists invited to attend Pope John facebook.com/americamag most accomplished churchmen in U.S. Paul II’s meeting in September 1987 twitter.com/americamag history, a daily reminder that I stand with leaders of the entertainment and PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF on the shoulders of giants. The third communication industry in Los Angeles. Matt Malone, S.J. portrait from the right, on the bottom George Hunt, S.J., retired from EXECUTIVE EDITORS row, is that of George W. Hunt, S.J., America in 1998, at the conclusion of Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy the 11th editor in chief. A native of the magazine’s most prosperous year MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber Yonkers, N.Y., Father Hunt entered to date. He remains the longest serving LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. the Society of Jesus in 1954 and was editor in chief. Later that year, he was SENIOR EDITOR AND CHIEF CORRESPONDENT ordained a priest in 1967. He earned named director of the Archbishop Kevin Clarke a theology degree from Yale Divinity Hughes Institute for Religion and EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. -

Sunrise 75 for Email

Vladivostok Sunrise Mary Mother of God Mission Society Vladivostok Russia St Paul Minnesota Issue Number Seventy Five May 1, 2007 May 27 is moved again to October 7! At our Bishop’s request the re-consecration of our church is scheduled for October 7, 2007. He will also bless our Our Lady of Fatima Rectory, and a new Franciscan hospice for the homeless in Ussurysk earlier in the week. Sorry about the changes! organizations here in Russia are brand new, and there is much about them that needs improvement. Due to personnel problems, and in order to improve the organizational structure, the Catholic charitable organization "Caritas," which was begun by Bishop Joseph Werth, S.J., in 1992, simply needed to be reorganized, and Fr Myron, as the Dean of the Vladivostok Deanery, began tackling the problem in January of this year. Among other things, it was necessary to come up with plans for restructuring the entire WSC project and to find new directors for some of the Centers. That is where I came in. I'm the one who is "just beginning". Fr. Myron asked me to take on the duties of coordinating all the Women's Support Centers in the Deanery. I accepted the task even though I had no special training. I am not a doctor nor a psychologist, nor a nurse. I was not even a director of one of the Centers. I am a teacher and a religious sister of the Congregation of the Sisters of Charity of Saint Ann. But I think that together with all the other members of the board of Some Follow Through (And Others Are Just Beginning) by Sr. -

1 FIFTH WORLD CONGRESS for the PASTORAL CARE of MIGRANTS and REFUGEES Presentation of the Fifth World Congress for the Pastoral

1 FIFTH WORLD CONGRESS FOR THE PASTORAL CARE OF MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES Presentation of the Fifth World Congress for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees Address of Pope John Paul II Address of H.E. Stephen Fumio Cardinal Hamao to His Holiness Pope John Paul II Welcome Address, Card. Stephen Fumio Hamao Presentation of the Congress, Card. Stephen Fumio Hamao The Present Situation of International Migration World-Wide, Dr. Gabriela Rodríguez Pizarro Refugees and International Migration. Analysis and Action Proposals, Prof. Stefano Zamagni The Situation and Challenges of the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Asia and the Pacific, Bishop Leon Tharmaraj The Situation and Challenges of the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in North America, Rev. Anthony Mcguire Migrants and Refugees in Latin America, Msgr. Jacyr Francisco Braido, CS Situation and Challenges regarding the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Africa. Comments by a Witness and “Practitioner”, Abraham-Roch Okoku-Esseau, S.J. Situations and Challenges for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Refugees in Europe, Msgr. Aldo Giordano Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision of the Church on Migrants and Refugees. (From Post- Vatican II till Today), H.E. Archbishop Agostino Marchetto Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision of the Church for a Multicultural/Intercultural Society, H.E. Cardinal Paul Poupard Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision and the Guidelines of the Church for Ecumenical Dialogue, Card. Walter Kasper Starting afresh from Christ. The Vision and Guidelines of the Church for Inter-Religious Dialogue, Archbishop Pier Luigi Celata The Anglican Communion, His Grace Ian George 2 World Council of Churches, Ms Doris Peschke The German Catholic Church’s Experience of Ecumenical Collaboration in its Work with Migrants and Refugees, Dr. -

Sementes Inesperadas De Um Jardim (Des)Encantado

PONTIFÍCIA UNIVERSIDADE CATÓLICA DE SÃO PAULO PUC-SP ANTONIO GENIVALDO CORDEIRO DE OLIVEIRA Sementes inesperadas de um jardim (des)encantado A construção político-eclesial da identidade de Igreja local no Japão: Um estudo a partir do conflito com o Caminho Neocatecumenal Doutorado em Ciência da Religião São Paulo 2016 ANTONIO GENIVALDO CORDEIRO DE OLIVEIRA Sementes inesperadas de um jardim (des)encantado A construção político-eclesial da identidade de Igreja local no Japão: Um estudo a partir do conflito com o Caminho Neocatecumenal Doutorado em Ciência da Religião Tese apresentada à Banca examinadora da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para obtenção do Título de Doutor em Ciência da Religião sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. João Décio Passos. São Paulo 2016 Banca Examinadora ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ À Edward Williams, OMI e Konishi Yumiko A realização desta pesquisa foi possível graças ao apoio institucional da Fundação São Paulo - FUNDASP e da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES por meio do desconto parcial e das taxas que cobriram parte das mensalidades do curso. A CAPES através do Programa de Doutorado Sanduíche no Exterior - PDSE 99999.002393/2015-08, possibilitou a realização do período de pesquisas em Paris e Roma. Através do Santander International Summer Schools for Doctoral Students em convênio com as Universidades de Heidelberg e de Kyōto, foi possível viver a experiência de inserção no intercâmbio de pesquisa internacional em março de 2015. Agradecimentos Aos Missionários Oblatos de Maria Imaculada da Delegação Japão-Coréia, da Província do Brasil e da Comunidade de Fontenay-sous-Bois na França. -

"Welcoming the Stranger": a Dialogue Between Scriptural Understandings of and Catholic Church Policies Towards Migrant

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2009 "Welcoming the Stranger": A dialogue between Scriptural understandings of and Catholic Church policies towards migrants and refugees and pastoral praxis in the migrant and refugee pastoral care bodies within the Archdiocese of Perth Judith M. Woodward University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Woodward, J. M. (2009). "Welcoming the Stranger": A dialogue between Scriptural understandings of and Catholic Church policies towards migrants and refugees and pastoral praxis in the migrant and refugee pastoral care bodies within the Archdiocese of Perth (Doctor of Pastoral Theology (PThD)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/44 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Growth in human movement around the world has been one of the phenomenal aspects of globalization since the Second World War. Among these ‘people on the move’ those whom the United Nations Humanitarian Commission for Refugees has described as ‘persons of concern’ – refugees, displaced persons etc. – have increased at an alarming rate. They are now well in excess of the global population growth rate over the same period Many of these have moved into adjacent poorer developing countries but increasingly many are seeking asylum, either through official United Nations’ channels or through on-shore arrivals, in developing nations. -

Reading Reason with Emmanuel Eze Formations

Africana philosophy through his founding and editorship of the journal Philosophia Africana. The journal under Eze’s Symposia on Gender, Race and editorial leadership was committed to promoting “scholarly Philosophy exchanges across [the] historical and cultural boundaries” represented by African, African-American, and Afro- Volume 4, Special Issue on Emmanuel Eze, Spring 2008 Caribbean philosophical traditions. He also edited two http://web.mit.edu/sgrp important anthologies, Postcolonial African Philosophy: A Critical Reader (1997) and African Philosophy: An Anthology (1998), in which he took pains to draw contributions from writers working in all of these three subdisciplinary Reading Reason with Emmanuel Eze formations. Eze is perhaps best known for his critical reading of Kant’s JOHN PITTMAN anthropological writings and the philosophical ‘raciology’ Department of Art, Music, and Philosophy they contain, in his important article, “The Color of Reason: John Jay College of Criminal Justice The City University of New York The Idea of ‘Race’ in Kant’s Anthropology.” He extended that 899 Tenth Ave. critique to include Hume as well in his edited volume on Race New York, NY 10019 and the Enlightenment. Indeed, Emmanuel Eze was the USA contemporary writer who most consistently explored the [email protected] issue of the racial logic of the founding thinkers of the European enlightenment. In Achieving our Humanity: The Idea of a Postracial Future (2001), Eze extended that inquiry, Emmanuel Eze’s last and, terribly, posthumous book is On discussing at length the history of race conceptions in Reason: Rationality in a World of Cultural Conflict and Racism European thought, arguing that the modern origins of (2008). -

Social Contributions of the Catholic Church and Regional Solidarity: Analysis of the Korean-Japanese Conferences of Catholic Bishops

Korea Journal, vol. 59, no. 3 (autumn 2019): 5–26. © The Academy of Korean Studies, 2019 Social Contributions of the Catholic Church and Regional Solidarity: Analysis of the Korean-Japanese Conferences of Catholic Bishops Young-Kyun CHOI Abstract This study focuses on the history of regional solidarity among Catholic churches in East Asia as civil society organizations within the axiological frame of peace and social order. This paper endeavors to show the significant role of the Korean-Japanese Catholic bishops conferences, which have developed over 20 years, not only in contributing to civil and social solidarity but also to congeniality between the Korean and Japanese people. The cooperative activities of the Korean and Japanese bishops, which have their origins in efforts to deal with the historical issues between Korea and Japan, are considered purposeful undertakings in support of peace and order in the East Asia region. With the passage of time, the solidarity of the bishops has developed toward solving diverse regional social dislocation issues. The thrust of the bishops’ unified action can be seen in two aspects. The first is the bishops’ view that society, to become peaceful and mature, requires structural changes, and thus the cooperative efforts of the Korean and Japanese bishops have a socio-political orientation. The second aspect is its role as social charity, that is, volunteer work on behalf of the impoverished and social minorities. When regional peace and cooperation are threatened by the self-interests of nation-states, the case of regional cooperation by a religious organization demonstrates how civil society is able to contribute to the progress and peace of a given region beyond the efforts of national governments. -

Race in Early Modern Philosophy

Introduction I.1. Nature In 1782, in the journal of an obscure Dutch scientific society, we find a relation of the voyage of a European seafarer to the Gold Coast of Africa some decades earlier. In the town of Axim in present- day Ghana, we learn, at some point in the late 1750s, David Henri Gallandat met a man he describes as a “hermit” and a “soothsayer.” “His father and a sister were still alive,” Gallandat relates, “and lived a four- days’ journey inland. He had a brother who was a slave in the colony of Suriname.”1 So far, there is nothing exceptional in this relation: countless families were broken up by the slave trade in just this way. But we also learn that the hermit’s soothsaying practice was deeply informed by “philosophy.” Gal- landat is not using this term in a loose sense, either. The man he meets, we are told, “spoke various languages— Hebrew, Greek, Latin, French, High and Low German; he was very knowledgeable in astrology and as- tronomy, and a great philosopher.”2 In fact, this man, we learn, “had been sent to study at Halle and in Wittenberg, where in 1727 he was promoted to Doctor of Philosophy and Master of Liberal Arts.”3 On a certain understanding, there have been countless philosophers in Africa, whose status as such required no recognition by European institu- tions, no conferral of rank.4 On a narrower understanding, however, Anton Wilhelm Amo may rightly be held up as the first African philosopher in modern history. Gallandat tells us that after the death of Amo’s “master,” Duke August Wilhelm of Braunschweig- Wolfenbüttel, the philosopher- slave grew “melancholy,” and “decided to return to his home country.” 1 Verhandelingen uitgegeven door het Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen te Vlissingen, Negende Deel, Middelburg: Pieter Gillissen, 1782, 19– 20. -

Political and Cultural Identity in the Global Postcolony: Postcolonial Thinkers on the Racist Enlightenment and the Struggle for Humanity

www.acpo.cz recenzovaný časopis | peer-reviewed journal 2017 | vol. 9 | no. 1 | issn 1803–8220 ROOTHAAN, Angela (2017). Political and Cultural Identity in the Global Postcolony: Postcolonial Thinkers on the Racist Enlightenment and the Struggle for Humanity. Acta Politologica. Vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 31-44. Tento článek podléhá autorským právům, kopírování a využívání jeho obsahu bez řádného odkazování na něj je považováno za plagiátorství a podléhá sankcím dle platné legislativy. This article is protected by copyright. Copying and use of its content and presenting it as original research without proper citation is plagiarism, which is subject to legal sanctions. Katedra politologie Institutu politologických studií DepartmentFakulta of Political sociálních Science, věd u Instituteniverzity of Karlovy Political Studies Faculty of social sciences, charles university Political and Cultural Identity in the Global Postcolony: Postcolonial Thinkers on the Racist Enlightenment and the Struggle for Humanity Angela Roothaan1 Abstract: This paper investigates how, in the condition of postcolonialism, claims of political and cultural identity depend on the understanding of humanity, and how this understanding ultimately relates to historical agency. I understand postcolonialism as the condition that aims at the decolonization of thought of formerly colonized and former colonizers together – a condition that is global. I will construe my argument by discussing the following au- thors: Frantz Fanon, Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, Amilcar Cabral, Achille Mbembe and Michael Onyebuchi Eze. Fanon for his criticism of modern Western philosophy as dehumanizing the other; Emmanuel Eze for his in-depth critique of Kant and Hegel’s ideas of humanity and the racialised and racist frames of thought they left behind and both Fanon and Eze for their proposals to understand humanity as a project under construction; Amilcar Cabral for his views on the interrelatedness of political and cultural identity in a situation of the building of new nations. -

(Universals) in Aristotle

Rethinking Universalism and Particularism in African Philosophy: Towards an Eclectic Approach by Mutshidzi Maraganedzha Supervisor: Prof Bernard Matolino This dissertation is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy, in the School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics. College of Humanities, University of Kwa-Zulu Natal, Pietermaritzburg November 2019 Declaration The author declares that the content of this thesis is his work unless the contrary has been specifically indicated. This thesis has not been submitted in any form for any specific degree to any other university across the world. Citations, references and to a greater extend borrowed ideas are properly acknowledged within the text. Signed: __________________ _______________ Mutshidzi Maraganedzha Date Student No. 207505743 I declare that this work has been submitted with the approval of the University supervisor. Signed: __________________ _______________ Prof. Bernard Matolino Date School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics University of KwaZulu-Natal i Dedication I dedicate this thesis to my late father, Khamusi Samson Maraganedzha who passed-away at the beginning of my doctoral studies. ii Abstract The study focuses on the dispute between the universalists and particularists in the characterization of the nature of African philosophy. In African philosophy the debate is formulated as a dichotomy between the universalists and the particularists. At the center of this debate is the notion of ‘universal’ and its relationship to the particular. The universalists argue that the nature of (African) philosophy–its methodology and subject matter–has to be universal and should be the same when applied to Western and African thought systems. -

People on the Move

PEOPLE ON THE MOVE CIRCUS AND AMUSEMENT PARKS: ‘CATHEDRALS’ OF FAITH AND TRADITION, SIGN OF HOPE IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD PEOPLE ON THE MOVE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE PASTORAL CARE Suppl. OF MIGRANTS AND ITINERANT PEOPLE 117 XLII July-December 2012 Suppl. n. 117 PEOPLE ON THE MOVE XLII July-December 2012 Suppl. N. 117 Comitato Direttivo: Antonio Maria Vegliò, Presidente del PCPMI Joseph Kalathiparambil, Segretario del PCPMI Gabriele F. Bentoglio, Sottosegretario del PCPMI tel. 06.69887131 e-mail:RIÀFH#PLJUDQWVYD &RPLWDWR6FLHQWLÀFR &KLDUD $PLUDQWH )UDQFLV9LQFHQW $QWKR Q\ )DELR %DJJLR &DWHULQD %RFD $QDOLWD Candaten, Velasio De Paolis, Barnabe D’Souza, Christopher Hein, Johan Ketelers, 3DROR 0RUR]]R GHOOD 5RFFD *LDQFDUOR 3HUHJR%ULJLWWH3URNVFK$QGUHD5LFFDUGL 9LQFHQ]R5RVDWR0DULR6DQWLOOR*LRYDQQL Giulio Valtolina, Stefano Zamagni, Laura =DQIULQL&DWDOGR=XFFDUR Comitato di Redazione: Assunta Bridi, José Brosel, Nilda Castro, %UXQR &LFHUL )UDQFHVFD 'RQj $QWRQHOOD Farina, Angelo Forte, Matthew Gardzinski, $QJHOR *UHFR 7HUHVD .OHLQ $OHVVDQGUD +DOLQD 3DQGHU 0DULD 3DROD 5RQFHOOD 0DUJKHULWD 6FKLDYHWWL )UDQV 7KRROHQ Robinson Wijeinsinghe. Segreteria tecnica: 0DVVLPR%RL*LDQFDUOR&LULVDQR2OLYHUD *UJXUHYLF $PPQHH8IÀFLRDEE Abbonamento Annuo 2012 tel. 06.69887131 fax 06.69887111 2UGLQDULR,WDOLD ½ ZZZSFPLJUDQWVRUJ (VWHUR YLDDHUHD (XURSD ½ 5HVWRGHOPRQGR ½ Stampa: 8QDFRSLD ½ /LWRJUDÀD/HEHULW 9LD$XUHOLD5RPD 1 PEOPLE ON THE MOVE Rivista del Pontificio Consiglio della Pastorale per i Migranti e gli Itineranti PubblicazioneM semestrale con due supplementi Breve -

An Appraisal of the Challenges Confronting the Nature of African Philosophy

AN APPRAISAL OF THE CHALLENGES CONFRONTING THE NATURE OF AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY Williams O. ASO Introduction The place of adequate definition on any subject of discussion cannot be overemphasized. A proper definition of an idea is a true path way to better understanding and appreciation of its components, from the main topic to the minutest parts. Hence, a good definition of an academic subject tele-guides those who have interest in the subject to know what the subject holds, its concerns and what distinguishes it from other related subjects. A definition that involves all these concerns will help participants in the discussion at stake to avoid misconceptions and misgivings in one sense and overcome ambiguities and equivocations in another sense. As a matter of fact, a justified definition is necessary for African philosophy to determine its scope, to illustrate its characteristics, to identify its concerns and inherent problems. This attempt will make anybody in an academic environment to have a clearer picture of what is African philosophy. There is no doubt that countless definitions of 138 139 African philosophy may come up as a result of diverse impulses from the background, the school, the culture and appreciated methodology of each philosopher. However, a notable parameter is necessary to judge if a particular definition of African philosophy is credible and acceptable. What count most in the definition of African philosophy is not as important as the relationship that such definition must have with African worldview. Therefore, any definition of African philosophy that reflects on African perspective either by an African or non-African is relevant for the understanding of African philosophy.