Hinckley Retail Capacity Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leicester and Leicestershire City Deal

Leicester and Leicestershire City Deal Page | 1 Executive Summary Leicester and Leicestershire is a diverse and dynamic local economy and its success is integral to driving economic growth in the United Kingdom. The area is home to just under 1 million residents and over 32,000 businesses, many in the manufacturing and logistics sectors. Leicester and Leicestershire also benefits from its location at the heart of the UK road network and close proximity to both the second largest freight handling airport in the UK and London. The area provides employment for 435,000 people and generates an estimated gross value added of £19.4 billion. Despite these strengths Leicester and Leicestershire faces a series of challenges: more than 25,000 jobs were lost between 2008 and 2011 (nearly twice the national average); youth unemployment is relatively high within the city of Leicester and parts of the county; and whilst 70% of small and medium enterprises have plans for growth many find accessing the right type of business support is complex. Some local businesses also note difficulties in filling vacancies. As part of the area’s wider Growth Strategy the City Deal seeks to tackle these key barriers. Over its lifetime the Leicester and Leicestershire Enterprise Partnership expects that the City Deal will deliver: A new employment scheme targeted at 16-24 year olds that will reduce youth unemployment by 50% by 2018, deliver 3,000 new apprenticeships and 1,000 traineeships and work placements. An innovative new employment and training scheme for young offenders. Improved co-ordination of business support services and a range of innovative business support programmes. -

Hinckley Le10 2Jq

WATLING STREET HINCKLEY LE10 2JQ FORECOURT & CONVENIENCE STORE INVESTMENT LOCATED IN CLOSE PROXIMITY TO M69 MOTORWAY WITH AN UNEXPIRED TERM OF 17 YEARS FORECOURT & CONVENIENCE STORE INVESTMENT LOCATED IN CLOSE WATLING STREET, HINCKLEY, LE10 2JQ PROXIMITY TO M69 MOTORWAY WITH AN UNEXPIRED TERM OF 17 YEARS INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS PROPOSAL ■ Strategically located Petrol Station Forecourt and foodstore, ■ Let until March 2038 with no break option - ■ We are instructed to seek offers in excess of 170 yards away from junction 1 of the M69 motorway unexpired term of 17 years £1,650,000 (One Million, Six Hundred and ■ Situated southbound on the busy A5 trunk road, being the ■ Let to Rontec Properties (No.4) Limited, Fifty Thousand Pounds) subject to contract final petrol station before the motorway guaranteed by Rontec Roadside Retail Limited and exclusive of VAT. A purchase at this level ■ Comprising of 2,342 sq ft of retail accommodation and Rontec Service Stations 1A reflects a Net Initial Yield of 5.75% rising and 8 petrol pumps, occupying a site of 0.34 acres ■ Additional guarantee by the undoubted covenant to 6.00% in June 2024 after allowing for ■ Located south of Hinckley town, 13 miles of Co-operative Group Food Limited until 2027 purchaser’s costs of 6.15%. from Leicester and Coventry ■ Estimated retail sales of £570,000 per annum and fuel volume ■ Producing an income of £100,814.76 per annum of 4.3m litres per annum subject to fixed annual uplifts of 2% ■ Freehold FORECOURT & CONVENIENCE STORE INVESTMENT LOCATED IN CLOSE WATLING STREET, HINCKLEY, LE10 2JQ PROXIMITY TO M69 MOTORWAY WITH AN UNEXPIRED TERM OF 17 YEARS Stoke-on-Trent Newcastle-under-Lyme North (M6) North (M1) Sheffield Stoke on Trent, NOTTINGHAM Manchester, Liverpool LOCATION DERBY M1 Hinckley is the second largest town in Leicestershire, located at the midpoint between Leicester and Coventry approximately 13 miles M6 (21 km) south west of Leicester town centre, 13 miles (21 km) north east of Coventry town centre and 5 miles (8km) north east of Nuneaton. -

Can Arcadia Stop the Rot? As Sir Philip Green's Fashion Empire Faces Tough Times, Gemma Goldiingle and George Macdonald Analyse How It Can Turn the Corner

14 Retail Week June 16, 2017 Can Arcadia stop the rot? As Sir Philip Green's fashion empire faces tough times, Gemma Goldiingle and George MacDonald analyse how it can turn the corner ashion giant Arcadia, owner of famous One of the Arcadia brands facing the fascias such as Topshop, Evans and most competition is the jewel in its Dorothy Perkins, suffered a steep fall in crown - Topshop. profits last year. The retailer was once a haven for FThe retailer's annual report and accounts, fashion-forward young shoppers and filed at Companies House this week, showed exuded cool. that earnings took a£129.2m hit from excep- However, over the past decade tionals as onerous lease provisions and costs Zara, H&M and Primark have surged relating to the now defunct BHS had an impact. in popularity while pureplay rivals But even before such items were taken such as Asos and Boohoo are also rivalling into account, operating profit slid 16% from Topshop in the style stakes. £252.9m to £211.2m on sales down from Some industry observers believe it is no £2.07bnto£2.02bn. longer the automatic first-choice shopping Arcadia faces many of the same problems destination for its young customers. as its peers, such as changes to consumer GlobalData analyst Kate Ormrod says: spending habits and currency volatihty, as well "Online pureplays are now the first port of as some particular challenges of its own. call. They are dominating in terms of customer Arcadia said: "The retail industry continues engagement. Shoppers are on there first thing Has Topshop(above, to experience a period of major change as in the morning and last thing at night." right) lost its cool customers become ever more selective and Ormrod says that Topshop needs to do more despite attempts to value-conscious and advances in technology to engage its customers online and connect remain current? open up more diverse, fast-changing and more with popular culture. -

Jurys Inn Hinckley Island Jurys Inn Hinckley Island

JURYS INN HINCKLEY ISLAND JURYS INN HINCKLEY ISLAND 600 Free Spaces TO HINCKLEY B4109 TO M1 JCT 21 & LEICESTER SKETCHLEY HILL RUGB East Midlands (28 miles) Birmingham Intl (22.1 miles) Y ROAD TO M42 JCT 10 & TAMWORTH A5 Hinckley (2.1 miles) Nuneaton (5 miles) JCT 1 M69 Hinckley town centre WA TLING ST D B4109 M69 R A5 Y E TO M1 JCT 20 BROCHURE L K & LONDON C N TO I M6 JCT 2 H For multi location enquiries, please contact our dedicated Jurys Meeting team on: Tel: 0845 525 6338 Email: [email protected] For all other enquiries, contact the hotel directly: JURYS INN HINCKLEY ISLAND Watling Street Hinckley Leicestershire LE10 3JA Tel: 01455 631 122 Email: [email protected] Or enquire online at jurysinns.com/meetings PERFECTLY LOCATED YOUR HOME Jurys Inn Hinckley Island is located just off Junction 1 of the M69 motorway between Leicester and Coventry. The FOR BUSINESS hotel is only 2.1 miles from Hinckley railway station and offers excellent access to the M6, M69 and M1 motorways, Birmingham and East Midlands Airport, mak- Whether you want to hold a ing it a perfect base for exploring central England. Local meeting, seminar, conference, attractions include The National Space Centre, Bosworth Battlefield, Twycross Zoo & Warwick Castle. training day, workshop or event, Jurys Inn have it covered. Jurys Meetings is shorthand for excellence and reliability. Room design is stylish and light, and equipment is first class. The smooth efficiency of our highly trained, dedicated Jurys Meetings team means consistency, reliability and a completely stress-free experience. -

Leics HMA ELR Report - Appendices Final.Doc PACEC Contents

Leicester and Leicestershire HMA Employment Land Study A report prepared by PACEC With Warwick Business Management Ltd on behalf of Leicester Shire Economic Partnership PACEC Public and Corporate Economic Consultants 49-53 Regent Street Cambridge CB2 1AB Tel: 01223 311649 Fax: 01223 362913 504 Linen Hall 162-168 Regent Street London W1R 5TB Tel: 020 7734 6699 Fax: 020 7434 0357 e-mail: [email protected] February 2009 Ref: H:\0712\12LSEP\Rep\Final\Leics HMA ELR Report - Appendices Final.doc PACEC Contents Contents Appendix A Commuting Flows ..................................................................................................... 2 Appendix B Employment Sector Definitions .............................................................................. 10 Appendix C Floorspace Definitions ............................................................................................ 11 C1 ODPM Floorspace Definitions up to 2004 ...................................................................... 11 C2 ODPM Floorspace Definition 2005 onwards .................................................................. 12 Appendix D Outstanding Planning Permissions and Allocations, March 2007 .......................... 14 Appendix E Site Assessment of Employment Areas which remain Wholly or Partly Undeveloped 20 Appendix F Floorspace Densities .............................................................................................. 23 F1 Strategic Warehousing ...................................................................................................... -

FOR SALE Eastwoods Service Station Petrol Service Station with Bungalow, Industrial Units and Storage Land Total Site Area: 1.12 Hectares (2.76 Acres)

FOR SALE Eastwoods Service Station Petrol Service Station with Bungalow, Industrial Units and Storage Land Total site area: 1.12 hectares (2.76 acres) Ashby Road Stapleton Leicestershire LE9 8JE Guide Price £1,200,000 Not to Scale. For Illustration Only 47 D A4 Y ROA ASHB 7 44 A D OA Y R HB AS EASTWOODS SERVICE STATION Property Highlights • Fully trading, owner-operated Petrol Filling Station with shop, available as a going concern. • Alternatively, the Service Station could be closed, the property providing an excellent mixed-use investment and asset management opportunity. • Also, the property provides an excellent opportunity for an owner occupier industrial user with a variety of units and extensive yard areas. • Available Freehold with vacant possession. • Three bedroom bungalow with indoor swimming pool. • Haulage operator centre with O licence for 20 vehicles and 8 Trailers • Industrial and storage units totalling 1,148.63 sq m (12,362 sq ft). • MOT Testing Station • Also car wash and ancillary offices. • Total site area: 1.12 hectares (2.76 acres), including yard of 0.335 hectares (0.83 acres) Ashby Road, Stapleton, Leicestershire LE9 8JE Stafford Burton upon Trent M6 M1 Location M42 Eastwoods Service Station fronts the Cannock Lichfield Lichfield Market A447 Ashby Road equidistant Bosworth between Hinckley (5 miles to the Tamworth Leicester south) and Coalville (5 miles to the A444 Walsall M6 north), near the villages of Stapleton, TOLL A5 Sutton Cheney, Cadeby and Kirkby Hinckley Mallory. Market Bosworth is Wolverhampton approximately two miles to the Nuneaton M1 north-west. Adjacent and nearby are Birmingham M69 M6 extensive Garden Centres, the Mallory LutterworthLutterworth Park Motor Racing Centre, and the Bosworth Battlefield Visitor Centre. -

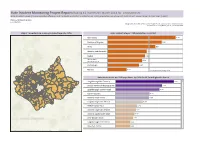

Himp Maps Page2

Hate Incident Monitoring Project Report: Rolling 12 months ll March 2014 for Leicestershire Hate Incident Levels (Police recorded offences and incidents and HIMP incidents) per 1000 populaon are shown at District and Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Choose Partnership Area Leicestershire Designed by Karen Earp, Research & Insight Team , Leicestershire County Council, Contact: [email protected] , 0116 305 7260 Map of Leicestershire showing incident levels by LSOA Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by district. -1 Charnwood 0.76 -1 Oadby and Wigston 0.61 -1 Blaby 0.53 0 Hinckley and Bosworth 0.44 0 Melton 0.42 North West 0 0.39 Leicestershire 0 Harborough 0.35 0 Rutland 0.21 Leicestershire Average 0.46 Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by LSOA for All from highest to lowest -9 Loughborough Bell Foundry 9.27 -7 Oadby The Parade & Leicester Ra.. 7.40 -7 Loughborough Toothill Road 7.00 -5 Coalville Centre 5.44 -5 Hinckley Town Centre 5.35 -4 Loughborough Centre South 4.34 -3 Melton Egerton East 3.46 -3 Hinckley Town Centre North 3.24 -3 Hinckley Castle South West 3.06 -3 Lile Bowden South 2.83 -2 Loughborough Centre West 2.39 -2 Measham Centre 2.39 -2 Loughborough Meadow Lane 2.37 About Tableau maps: www.tableausoftware.com/ mapdata Hate Incident Monitoring Project Report: Rolling 12 months ll March 2014 for Blaby Hate Incident Levels (Police recorded offences and incidents and HIMP incidents) per 1000 populaon are shown at District and Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) Choose Partnership Area Blaby Designed by Karen Earp, Research & Insight Team , Leicestershire County Council, Contact: [email protected] , 0116 305 7260 Map of Blaby showing incident levels by LSOA Hate incident rate per 1000 populaon by district. -

Transport Trends in Leicestershire, 2015

Leicestershire County Council Transport Trends in Leicestershire 2015 Network Data and Intelligence (NDI) Leicestershire Transport Trends 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Traffic Growth ................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Traffic Volumes ............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Traffic Composition ......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Traffic Speeds and Delay ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Prepay Technologies Prepay Technologies: the Reason Why?

PrePay Technologies PrePay Technologies: the reason why? Accor Services’ business model Affiliate the Establish Ticket Float Programme Redemption Final Acceptance Corporate Production mgt design Users Network relationships & Delivery 1. Network access 2. Issuer status 3. Transaction and control & competency authorization/ processing PPT integrates 3 key stages … and speeds up in the Value Chain: our time to market for 1. Network access 2. Issuer status Electronic Transactions 3. Transaction authorization / Processing 2 PrePay Technologies: A Prepaid Card Solutions Provider Acquisition in September 2007 A value-added processing platform for Prepaid Card solutions 60 specialist staff dedicated to prepaid Business volume: 400 Million € # transactions: 40 Million 3 3 Expertise: A fully integrated services model Programme design, integration & support • Programme delivery and management • 24/7 support, fully customisable self service options Issuing & processing • In house processing on closed, filtered & open payment networks • MasterCard certified prepaid processor Compliance & regulation • E-Money licence, FSA regulated (UK) • ‘Passported’ across Europe • Compliance & regulatory support (KYC) 4 4 Business Model: A fully integrated services model Set up the Ongoing Business Services International Regulatory Regulatory Transaction Program Program scheme operations Approval & processing design implementation handling (E-Money Support (MasterCard) compliance) Set-up fees Fee per transaction 5 Card cycle Card Issuing Card Card usage Activation -

Hinckley and Bosworth Nominated Candidates

Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll Leicestershire County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for Burbage Division Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* HILL (address in Social Chettle David * Roger Hinckley & Democratic Wallis Sonia J ** Bosworth) Party MARTIN 1 Kestrel Close, Labour Party Clayden Hugh C * Robert Burbage, LE10 Clayden Anna M P ** 2PA WALKER 16 Denis Road, Liberal Inman Celia P * Barry Richard Burbage, LE10 Democrat Focus Lynch Maureen V ** 2LR Team WRIGHT (address in The Clayton Andrew T * Amanda Victoria Hinckley & Conservative MacDonald David W ** Bosworth) Party Candidate The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. A POLL WILL BE TAKEN on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of Parish Councillors, the election of the Police and Crime Commissioner and the referendum on the adoption of the Burbage Neighbourhood Plan. Dated 8 April 2021 Bill Cullen Deputy Returning Officer Hinckley Hub Rugby Road Hinckley Leicestershire LE10 0FR Statement of Persons Nominated and Notice of Poll Leicestershire County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for De Montfort Division Reason why Name of Description -

Hinckley and Bosworth

HINCKLEY & BOSWORTH DISTRICT PROFILE JANUARY 2010 JSNA District Level Report JSNA findings for Hinckley and Bosworth 1. Demography In 2007 there were an estimated 104,400 people resident in Hinckley and Bosworth. 95% of the population is white British and 2% is White Other. Hinckley and Bosworth is affected by socio-economic deprivation with 7.1% of the population living in neighbourhoods that have been classified as deprived nationally (4th quintile). However, there are no residents within the most deprived quintile within this district. Whilst this is similar to the value for Leicestershire it is well below the national average of 20% of people. Priority Neighbourhoods Hinckley and Bosworth has five priority neighbourhoods, Earl Shilton, Barwell, Hinckley, Burbage and Bagworth. Maps of the priority neighbourhoods are available on the Leicestershire Statistics and Research Online website: http://www.lsr-online.org/reports/leicestershire_laa_priority_neighbourhoods 2. Housing and accommodation needs Hinckley and Bosworth is a mostly rural area. The main settlements, Hinckley, Barwell, and Earl Shilton, are fairly different . Using Output Area Classifications to gain a general view suggests that Hinckley contains more higher income households and Earl Shilton is relatively more working class, but these are generalisations and cover a substantial variety. Most of the children of school age in the main settlements are White British. The largest ethnic minority groups are ‘Other White’ and ‘Asian/British Indian’. Properties in the main settlements are mainly owner occupied 3 bed houses, though there are significant numbers of both 2 bed flats and houses. There is very little private rented property (though this is likely to have increased since 2001) throughout the borough. -

Updates out of Hours (OOH) Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) Forum Community Health Care H&B

Updates Out of Hours (OOH) Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) Forum Community Health Care H&B Alan Plumpton Updates Sharing of Patient information leaflet. • University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust • Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust • Northern Doctors Urgent Care Ltd – Oadby and Wigston Walk-in Medical Centre – Melton Mowbray Hospital Minor Injury and Illness Service – Market Harborough Minor Injury and Illness Unit – Rutland Memorial Hospital Minor Injury and Illness Unit • Central Nottingham Clinical Services – Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland Out of Hours Service – Urgent Care Centre, Loughborough • Derbyshire Health United – NHS 111 • East Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Trust • George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust – Urgent Care Centre Leicester • Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Families (SSAFA) Walk-in Centre 112 • When making an emergency call on a mobile phone use the number 112 instead of 999. • This enables the operator to pinpoint you position to within 5 metres • 999 gives only a general position Out of Hours (OOH) – Special Measures • Christine Green is Acting CEO replaces Richard Carroll • 81 recommendations from CQC only 3 left to address. On target to complete these. • Contracts up for renewal of OOH and 111. Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) Forum Speeding up A&E at Leicester Royal Infirmary 3rd Nov The Emergency Dept at LRI will work along side “Lakeside,” (providers who are made up of GP’s in Corby).. They make sure that when a patient walks in they will be triaged by senior clinicians. They can then be sent to - same day clinics if they have an on going condition - referral back to GP. - UCC (Urgent Care Centre) - A&E Community Healthcare reforms in Hinckley and Bosworth • Consultation has taken place over 18 mths (George Ward Centre June 15th) plus meetings at the Golf Club, and other interested groups (Dementia, Youth groups and PPG’s) • 12 Action points plus Fact sheets on your seats show what has changed so far based on patient comments.