The Princess Is in Another Castle: Multi-Linear Stories in Oral Epic and Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

The Art of the Graphic Novel

Eric Shanower The Art of the Graphic Novel Adapted from an address delivered at the 2004 ALAN Workshop. Mr. Shanower accompanied his talk with a beautiful slide show and refers to the slides in this address. raphic novel” is an and, for better or for worse, it awkward term. The seems we’re stuck with it. “G “graphic” part is I’m here to speak to you okay, graphic novels always have about the art of the graphic novel. graphics. It’s the “novel” part When you hear the phrase, the that’s a problem, because graphic art of the graphic novel, you likely novels aren’t always novels told think of the drawings, rather than with drawings. They can be the story. But I bet most of you works of non-fiction or collec will agree that writing is an art tions of short stories or, really, just as drawing is. I’m going to anything you can think of that talk about both. consists of drawings that convey Let’s forget about graphic narrative between two substan novels for a moment and think tial covers. about what I call cartooning. Or The term “graphic novel” you can call it “comic art” or isn’t much better or more “sequential art.” Cartooning is the accurate a description than the art of telling a story in pictures, term “comic book.” But “comic often using written words as in book” has pejorative connota integral part of the drawing. The tions, and many people seem history of cartooning starts a bit either embarrassed or dismissive nebulously. -

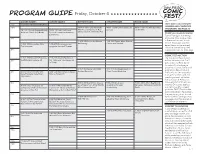

PROGRAM GUIDE Friday, October 4

PROGRAM GUIDE Friday, October 4 GARDEN ROOM 1 GARDEN ROOM 2 BRITTANY ROOM CRESCENT ROOM EATON ROOM INFO ABOUT AUTOGRAPH 11AM 11AM-12PM Ask Don Glut Anything SIGNING AND CHILDREN’S 12PM Noon-1:00PM I Like My Books Noon-1:00PM Comic Issues Live Noon-1:00PM It’s All Happening PROGRAMS: SEE PAGE 10 12:15-1:15 Early Origins of Early 12:15-1:15 Star Trek: Deep With Pictures—Comics in Aca- podcast on the Web demic Libraries, the SDSU Way American Comic Strip Books Space Nine and the American COMIC FEST FILM PROGRAM Experience Comic Fest again is showing 1PM night-time films, most of them 1:15-2:15 Comics You Should 1:15-2:15 Tarzan: Myth, Culture, in the time-honored 16 mm format. Come join us in the 1:30-2:30 One-on-One With 1:30-2:30 Creation of a lan- Be Reading Comics and Fandom Eaton Room for the movies! Eric Shanower guage for Game of Thrones The schedule will be posted 2PM outside the room for both days. COMIC FEST AUCTION 2:45-3:45 IDW Artist’s Editions— 2:45-3:45 Comics Fandom in The first Comic Fest Auction 3PM Scott Dunbier Explains All the 1960s and ‘70s Compared will be Saturday, Oct. 5 at 5 to Today p.m. under the Tent. Items for sale will include some great comics, toys, DVDs and 3:45-4:45 One-on-One With 3:45-4:45 Creating Comics—A original art. We will have a Andrew Biscontini Crash Course Workshop 4PM 4:00-5:00 One on One with 4:00-5:00 Star Trek Deep Space live comic art demonstration Jerry Pournelle (Larry Niven Nine vs. -

Publisher's Note

PUBLISHER’S NOTE Graphic novels have spawned a body of literary criti- the graphic novel landscape. It contains works that are FLVPVLQFHWKHLUHPHUJHQFHDVDVSHFL¿FFDWHJRU\LQWKH self-published or are from independent houses. The SXEOLVKLQJ¿HOGDWWDLQLQJDOHYHORIUHVSHFWDQGSHUPD- entries in this encyclopedic set also cover a wide range nence in academia previously held by their counterparts RISHULRGVDQGWUHQGVLQWKHPHGLXPIURPWKHLQÀXHQ- in prose. Salem Press’s Critical Survey of Graphic tial early twentieth-century woodcuts—“novels in Novels series aims to collect the preeminent graphic pictures”—of Frans Masereel to the alternative comics novels and core comics series that form today’s canon revolution of the 1980’s, spearheaded by such works for academic coursework and library collection devel- as Love and Rockets by the Hernandez brothers; from RSPHQWR൵HULQJFOHDUFRQFLVHDQGDFFHVVLEOHDQDO\VLV WKHDQWKURSRPRUSKLFKLVWRULFDO¿FWLRQRIMaus, which of not only the historic and current landscape of the in- attempted to humanize the full weight of the Holo- terdisciplinary medium and its consumption, but the caust, to the unglamorous autobiographical American wide range of genres, themes, devices, and techniques Splendor series and its celebration of the mundane; that the graphic novel medium encompasses. and from Robert Crumb’s faithful and scholarly illus- The combination of visual images and text, the em- trative interpretation of the Book of Genesis, to the phasis of art over written description, the coupling of tongue-in-cheek subversiveness of the genre -

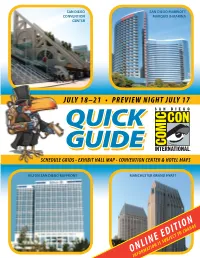

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

CITIZEN #166 Catalogue.Indd

Bonjour à toutes et à tous, Je vous en touchais deux mots, le mois dernier, c’est désormais à J-4 de la Brade- rie de Lille que ces quelques lignes sont désormais saisies ! édito Autrement dit la vague va bientôt nous recouvrir ! Bref rien d’autre que ce à quoi nous sommes habitués maintenant ! Le 1er septembre 2015 AstroCity fête ses …..dix-sept ans ! 17…. Bref ni sensiblerie ni nostalgie ici, que du plaisir ! J’imagine que vous avez tous passé une période estivale riche en repos et autre sieste et que vous attaquez d’arrache-pied ce mois de septembre 2015 ? Vous trouverez ici présentés les nouveautés d’octobre … que du bon ! Mais c’est une habitude avec nous !!! Plus sérieusement, sur le modèle du FCBD, nous allons profi ter du dernier week- end d’octobre pour organiser un special Halloween, si vous êtes dans les parages, si vous devez planifi er un déplacement dans la capitale des Flandres ? Bref…..venez ! news d’OCTOBRE 2015 d’OCTOBRE news Damien, Fred & Jérôme – le service VPC dans son intégralité ! la cover du mois : I HATE FAIRYLAND #1 par Skottie Young Le logo astrocity et la super-heroïne Un peu de lexique... “astrogirl” ont été créés par Blackface. Corp et sont la propriété exclusive de Damien GN pour Graphic novel : La traduction littérale de ce terme est «roman graphique» Rameaux & Frédéric Dufl ot au titre de la OS pour One shot : Histoire en un épisode, publié le plus souvent à part de la continuité régulière. société AstroCity SARL. Mise en en page et TP pour Trade paperback : Un trade paperback est un recueil en un volume unique de plusieurs comic-books qui regroupe un arc complet charte graphique du magazine Citizen et du site internet astrocity.fr par Blackface.Corp HC pour Hard Cover : Un hard cover est un recueil en version luxueuse, grand format et couverture cartonnée de plusieurs comic-books. -

DIABC SUMMER 2006.Indd

BOOKS AND TRADE PAPERBACKS TABLE OF CONTENTS 13th Son: Worse Thing Waiting . 44 Oh My Goddess! Volume 3 . 30 Aeon Flux . 21 Old Boy Volume 1 . 50 The Artist Within . 43 Path of the Assassin Volume 1 . 31 B.P.R.D.: The Black Flame . 39 Penny Arcade Volume 2: Epic Legends Berserk Volume 12 . 32 of the Magic Sword Kings . 49 BMWFilms.com Presents The Hire . 20 Pete Von Sholly’s Cannon God Exaxxion Stage 5 . 55 Extremely Weird Stories . 42 The Comics: An Illustrated History of Reiko the Zombie Shop Volume 3 . 26 Comic Strip Art . 43 Revelations . 44 Conan and the Demons of Khitai . 36 Saiyuki Reload Anime Manga Conan Volume 3: The Tower Volume 1 . 53 of the Elephant and Other Stories . 37 Scary Book Volume 2: Insects . 18 Concrete Volume 5: School Zone Volume 2 . 35 Think Like a Mountain . 20 Star Wars Omnibus: Concrete Volume 6: Strange Armor . 41 X-Wing Rogue Squadron Volume 1 . 23 Crying Freeman Volume 2 . 26 Star Wars: Clone Wars Adventures Ctrl-Alt-Del Volume 3. 46 Volume 6 . 48 De:Tales . 38 Star Wars: Clone Wars Dreadlful Ed . 24 Volume 9—Endgame . 48 Eden: It’s an Endless World! Volume 3 . 18 Star Wars: Honor and Duty . 22 Eden: It’s an Endless World! Volume 4 . 50 Sudden Gravity . 38 Emily the Strange Volume 1 . 45 Tarzan: The Joe Kubert Years Volume 3 . 36 Go Girl!: Robots Gone Wild! . 55 Trigun Maximum Volume 9 . 19 Gungrave Archive . 27 Trigun Maximum Volume 10 . 53 Haibane Renmei Anime Manga . 19 Usagi Yojimbo: Volume 20 Harlan Ellison’s Dream Corridor Glimpses of Death . -

The Baum Bugle

Fourth Draft Three Column Version August 15, 2002 The Baum Bugle The Journal of the International Wizard of Oz Club Index for Volumes 1-45 1957-2001 Volumes 1 through 31: Frederick E. Otto Volumes 32 through 45: Richard R. Rutter Dedications The Baum Bugle’s editors for giving Oz fans insights into the wonderful world of Oz. Fred E. Otto [1927-95] for launching the indexing project. Peter E. Hanff for his assistance and encouragement during the creation of this third edition of The Baum Bugle Index (1957-2001). Fred M. Meyer, my mentor during more than a quarter century in Oz. Introduction Founded in 1957 by Justin G. Schiller, The International Wizard of Oz Club brings together thousands of diverse individuals interested in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and this classic’s author, L. Frank Baum. The forty-four volumes of The Baum Bugle to-date play an important rôle for the club and its members. Despite the general excellence of the journal, the lack of annual or cumulative indices, was soon recognized as a hindrance by those pursuing research related to The Wizard of Oz. The late Fred E. Otto (1925-1994) accepted the challenge of creating a Bugle index proposed by Jerry Tobias. With the assistance of Patrick Maund, Peter E. Hanff, and Karin Eads, Fred completed a first edition which included volumes 1 through 28 (1957-1984). A much improved second edition, embracing all issues through 1988, was published by Fred Otto with the assistance of Douglas G. Greene, Patrick Maund, Gregory McKean, and Peter E. -

Preuzmi PDF 1.26 MB

Zastupljenost i važnost zbirke stripova i grafičkih romana u knjižnici - knjižnica Vrapče kao primjer dobre prakse Baj Zorojević, Aleksandra Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2021 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:735607 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FILOZOFSKI FAKULTET ODSJEK ZA INFORMACIJSKE I KOMUNIKACIJSKE ZNANOSTI SMJER BIBLIOTEKARSTVO Ak. god. 2020./2021. Aleksandra Baj Zorojević Zastupljenost i važnost zbirke stripova i grafičkih romana u knjižnici - knjižnica Vrapče kao primjer dobre prakse Diplomski rad Mentor : Dr. sc. Sonja Špiranec, red. prof. Zagreb, ožujak 2021. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Izjavljujem i svojim potpisom potvrđujem da je ovaj rad rezultat mog vlastitog rada koji se temelji na istraživanjima te objavljenoj i citiranoj literaturi. Izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije napisan na nedozvoljen način, odnosno da je prepisan iz necitiranog rada, te da nijedan dio rada ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Također izjavljujem da nijedan dio rada nije korišten za bilo koji drugi rad u bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj ili obrazovnoj ustanovi. 2 Sadržaj Sažetak ................................................................................................................................................... -

A 25Th Year Celebration!

A 25th Year Celebration! www.twomorrows.com 2019 Update #2 THE WORLD OF TWOMORROWS In 1994, amidst the boom-&-bust of comic book speculators, THE JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR #1 was published for true fans of the medium. That modest labor of love spawned TwoMorrows Publishing, today’s premier purveyor of publications about comics and pop culture. Celebrate our 25th anniversary with this special retrospective look at the company that changed fandom forever! Co-edited by and featuring publisher JOHN MORROW and COMIC BOOK ARTIST/COMIC BOOK CREATOR magazine’s JON B. COOKE, it gives the inside story and behind-the-scenes details of a quarter- century of looking at the past in a whole new way. Also included are BACK ISSUE magazine’s MICHAEL EURY, ALTER EGO’s ROY THOMAS, GEORGE KHOURY (author of KIMOTA!, EXTRAORDINARY WORKS OF ALAN MOORE, and other books), MIKE MANLEY (DRAW! magazine), ERIC NOLEN-WEATHINGTON (MODERN MASTERS), and a host of other comics luminaries who’ve contributed to TwoMorrows’ output over the years. From their first Eisner Award-winning book STREETWISE, through their BRICKJOURNAL LEGO® magazine, up to today’s RETROFAN magazine, every major TwoMorrows publication and contributor is covered with the same detail and affection the company gives to its books and magazines. With an Introduction by MARK EVANIER, Foreword by ALEX ROSS, Afterword by PAUL LEVITZ, and a new cover by TOM McWEENEY! SHIPS NOVEMBER 2019! (224-page FULL-COLOR Trade Paperback) $34.95 • (Digital Edition) $15.95 ISBN: 978-1-60549-092-2 (240-page ULTRA-LIMITED HARDCOVER) -

'The Wizard of Oz' to 'Wicked': Trajectory of American Myth

FROM 'THE WIZARD OF OZ' TO 'WICKED': TRAJECTORY OF AMERICAN MYTH Alissa Burger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2009 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Gene S. Trantham Graduate Faculty Representative Don McQuarie Piya Pal Lapinski © 2009 Alissa Burger All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor The Wizard of Oz story has been omnipresent in American popular culture since the first publication of L. Frank Baum’s children’s book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz at the dawn of the twentieth century. Ever since, filmmakers, authors, and theatre producers have continued to return to Oz over and over again. However, while literally hundreds of adaptations of the Wizard of Oz story abound, a handful of transformations are particularly significant in exploring discourses of American myth and culture: L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900); MGM’s classic film The Wizard of Oz (1939); Sidney Lumet’s film The Wiz (1978); Gregory Maguire’s novel Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West (1995); and Stephen Schwartz and Winnie Holzman’s Broadway musical Wicked (2003). This project critiques theories of fixed or prescriptive American myth, instead developing a theory of American myth as active, performative and even, at times, participatory, achieved through discussion of the fluidity of text and performance, built on Diana Taylor’s theory of the archive and the repertoire. By approaching text and performance as fluid rather than fixed, this dissertation facilitates an interdisciplinary consideration of these works, bringing children’s literature, film, popular fiction, theatre, and music together in a theoretically multifaceted approach to the Wizard of Oz narrative, its many transformations, and its lasting significance within American culture. -

Hellas on Screen Hellas on Screen HABES 45 Alte Geschichte HABES – Band 45

magenta druckt HKS 18 The recent success of Hollywood blockbust- ers such as Troy, Alexander and 300 demon- strates how popular Greek antiquity still is and how well it can be marketed. Today as in the golden age of the peplum- genre, its myths, the Homeric heroes, the Attic tragedies, and – less frequently – historical personages such as Alexander the Great or the Spartan king Leo- nidas represent Hellas. The authors of this volume highlight the many and varied forms of the reception of ancient Hellas in the history of the cinema, from mythology to Roman Greece, from the era of silent films to the new millennium. In this, they are examining classic films, recent releases, and lesser known and often over- looked productions. Hellas on Screen Hellas on Screen HABES www.steiner-verlag.de 45 Alte Geschichte HABES – Band 45 Franz Steiner Verlag Franz Steiner Verlag Cinematic Receptions of Ancient 45 History, Literature and Myth Edited by Irene Berti / Marta García Morcillo García Morcillo ISBN 978-3-515-09223-4 Irene Berti / Marta Irene Berti / Marta Hellas on Screen Edited by Irene Berti / Marta García Morcillo HABES Heidelberger Althistorische Beiträge und Epigraphische Studien – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – Herausgegeben von Géza Alföldy, Angelos Chaniotis und Christian Witschel BAND 45 Hellas on Screen Cinematic Receptions of Ancient History, Literature and Myth Edited by Irene Berti / Marta García Morcillo Franz Steiner Verlag Stuttgart 2008 Coverabbildung: Medea (P.P. Pasolini, 1969) credits: Cinetext Bildarchiv, reg. num. 00164401 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen National- bibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar.