Identification of Specialized Pro- Resolving Mediator Clusters From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Oxygenation of Prostaglandin Endoperoxides and Arachidonic Acid

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Pharmacy 231 _____________________________ _____________________________ Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Oxygenation of Prostaglandin Endoperoxides and Arachidonic Acid Cloning, Expression and Catalytic Properties of CYP4F8 and CYP4F21 BY JOHAN BYLUND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2000 Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Pharmacy) in Pharmaceutical Pharmacology presented at Uppsala University in 2000 ABSTRACT Bylund, J. 2000. Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Oxygenation of Prostaglandin Endoperoxides and Arachidonic Acid: Cloning, Expression and Catalytic Properties of CYP4F8 and CYP4F21. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from Faculty of Pharmacy 231 50 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-4784-8. Cytochrome P450 (P450 or CYP) is an enzyme system involved in the oxygenation of a wide range of endogenous compounds as well as foreign chemicals and drugs. This thesis describes investigations of P450-catalyzed oxygenation of prostaglandins, linoleic and arachidonic acids. The formation of bisallylic hydroxy metabolites of linoleic and arachidonic acids was studied with human recombinant P450s and with human liver microsomes. Several P450 enzymes catalyzed the formation of bisallylic hydroxy metabolites. Inhibition studies and stereochemical analysis of metabolites suggest that the enzyme CYP1A2 may contribute to the biosynthesis of bisallylic hydroxy fatty acid metabolites in adult human liver microsomes. 19R-Hydroxy-PGE and 20-hydroxy-PGE are major components of human and ovine semen, respectively. They are formed in the seminal vesicles, but the mechanism of their biosynthesis is unknown. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction using degenerate primers for mammalian CYP4 family genes, revealed expression of two novel P450 genes in human and ovine seminal vesicles. -

Colorectal Cancer and Omega Hydroxylases

1 The differential expression of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid metabolising enzymes in colorectal cancer and its prognostic significance Abdo Alnabulsi1,2, Rebecca Swan1, Beatriz Cash2, Ayham Alnabulsi2, Graeme I Murray1 1Pathology, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences and Nutrition, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, AB25, 2ZD, UK. 2Vertebrate Antibodies, Zoology Building, Tillydrone Avenue, Aberdeen, AB24 2TZ, UK. Address correspondence to: Professor Graeme I Murray Email [email protected] Phone: +44(0)1224 553794 Fax: +44(0)1224 663002 Running title: omega hydroxylases and colorectal cancer 2 Abstract Background: Colorectal cancer is a common malignancy and one of the leading causes of cancer related deaths. The metabolism of omega fatty acids has been implicated in tumour growth and metastasis. Methods: This study has characterised the expression of omega fatty acid metabolising enzymes CYP4A11, CYP4F11, CYP4V2 and CYP4Z1 using monoclonal antibodies we have developed. Immunohistochemistry was performed on a tissue microarray containing 650 primary colorectal cancers, 285 lymph node metastasis and 50 normal colonic mucosa. Results: The differential expression of CYP4A11 and CYP4F11 showed a strong association with survival in both the whole patient cohort (HR=1.203, 95% CI=1.092-1.324, χ2=14.968, p=0.001) and in mismatch repair proficient tumours (HR=1.276, 95% CI=1.095-1.488, χ2=9.988, p=0.007). Multivariate analysis revealed that the differential expression of CYP4A11 and CYP4F11 was independently prognostic in both the whole patient cohort (p = 0.019) and in mismatch repair proficient tumours (p=0.046). Conclusions: A significant and independent association has been identified between overall survival and the differential expression of CYP4A11 and CYP4F11 in the whole patient cohort and in mismatch repair proficient tumours. -

Clinical Implications of 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid in the Kidney, Liver, Lung and Brain

1 Review 2 Clinical Implications of 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic 3 Acid in the Kidney, Liver, Lung and Brain: An 4 Emerging Therapeutic Target 5 Osama H. Elshenawy 1, Sherif M. Shoieb 1, Anwar Mohamed 1,2 and Ayman O.S. El-Kadi 1,* 6 1 Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton T6G 2E1, AB, Canada; 7 [email protected] (O.H.E.); [email protected] (S.M.S.); [email protected] (A.M.) 8 2 Department of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Medicine, Mohammed Bin Rashid University of 9 Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai, United Arab Emirates 10 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: 780-492-3071; Fax: 780-492-1217 11 Academic Editor: Kishor M. Wasan 12 Received: 12 January 2017; Accepted: 15 February 2017; Published: 20 February 2017 13 Abstract: Cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of arachidonic acid (AA) is an important 14 pathway for the formation of eicosanoids. The ω-hydroxylation of AA generates significant levels 15 of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) in various tissues. In the current review, we discussed 16 the role of 20-HETE in the kidney, liver, lung, and brain during physiological and 17 pathophysiological states. Moreover, we discussed the role of 20-HETE in tumor formation, 18 metabolic syndrome and diabetes. In the kidney, 20-HETE is involved in modulation of 19 preglomerular vascular tone and tubular ion transport. Furthermore, 20-HETE is involved in renal 20 ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and polycystic kidney diseases. The role of 20-HETE in the liver is 21 not clearly understood although it represents 50%–75% of liver CYP-dependent AA metabolism, 22 and it is associated with liver cirrhotic ascites. -

Fatty Acid Oxidation

FATTY ACID OXIDATION 1 FATTY ACIDS A fatty acid contains a long hydrocarbon chain and a terminal carboxylate group. The hydrocarbon chain may be saturated (with no double bond) or may be unsaturated (containing double bond). Fatty acids can be obtained from- Diet Adipolysis De novo synthesis 2 FUNCTIONS OF FATTY ACIDS Fatty acids have four major physiological roles. 1)Fatty acids are building blocks of phospholipids and glycolipids. 2)Many proteins are modified by the covalent attachment of fatty acids, which target them to membrane locations 3)Fatty acids are fuel molecules. They are stored as triacylglycerols. Fatty acids mobilized from triacylglycerols are oxidized to meet the energy needs of a cell or organism. 4)Fatty acid derivatives serve as hormones and intracellular messengers e.g. steroids, sex hormones and prostaglandins. 3 TRIGLYCERIDES Triglycerides are a highly concentrated stores of energy because they are reduced and anhydrous. The yield from the complete oxidation of fatty acids is about 9 kcal g-1 (38 kJ g-1) Triacylglycerols are nonpolar, and are stored in a nearly anhydrous form, whereas much more polar proteins and carbohydrates are more highly 4 TRIGLYCERIDES V/S GLYCOGEN A gram of nearly anhydrous fat stores more than six times as much energy as a gram of hydrated glycogen, which is likely the reason that triacylglycerols rather than glycogen were selected in evolution as the major energy reservoir. The glycogen and glucose stores provide enough energy to sustain biological function for about 24 hours, whereas the Triacylglycerol stores allow survival for several weeks. 5 PROVISION OF DIETARY FATTY ACIDS Most lipids are ingested in the form of triacylglycerols, that must be degraded to fatty acids for absorption across the intestinal epithelium. -

Identification of the Cytochrome P450 Enzymes Responsible for the X

FEBS Letters 580 (2006) 3794–3798 Identification of the cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for the x-hydroxylation of phytanic acid J.C. Komen, R.J.A. Wanders* Departments of Clinical Chemistry and Pediatrics, Emma Children’s Hospital, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands Received 27 March 2006; revised 26 May 2006; accepted 30 May 2006 Available online 9 June 2006 Edited by Sandro Sonnino tanic acid occurs effectively by bacteria present in the rumen Abstract Patients suffering from Refsum disease have a defect in the a-oxidation pathway which results in the accumulation of of ruminants. phytanic acid in plasma and tissues. Our previous studies have Phytanic acid accumulates in patients with adult Refsum dis- shown that phytanic acid is also a substrate for the x-oxidation ease (ARD, MIM 266500) which is due to a defect in the a-oxi- pathway. With the use of specific inhibitors we now show that dation pathway caused by mutations in one of two genes members of the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) family 4 class are including the PAHX gene which codes for phytanoyl-CoA responsible for phytanic acid x-hydroxylation. Incubations with hydroxylase [2,3], and the PEX7 gene which codes for the microsomes containing human recombinant CYP450s (Super- PTS2 receptor [4]. The majority of ARD patients have muta- TM somes ) revealed that multiple CYP450 enzymes of the family tions in the PAHX gene. The increased levels of phytanic acid 4 class are able to x-hydroxylate phytanic acid with the follow- in plasma and tissues are thought to be the direct cause for the ing order of efficiency: CYP4F3A > CYP4F3B > CYP4F2 > pathology of the disease. -

Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry

Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry View Article Online PAPER View Journal | View Issue A new synthetic protectin D1 analog 3-oxa-PD1 reduces neuropathic Cite this: Org. Biomol. Chem., 2021, n-3 DPA 19, 2744 pain and chronic itch in mice† Jannicke Irina Nesman,a Ouyang Chen, b Xin Luo, b Ru-Rong Ji, b Charles N. Serhan c and Trond Vidar Hansen *a The resolution of inflammation is a biosynthetically active process controlled by the interplay between oxygenated polyunsaturated mediators and G-protein coupled receptor-signaling pathways. These enzy- matically oxygenated polyunsaturated fatty acids belong to distinct families of specialized pro-resolving autacoids. The protectin family of mediators has attracted an interest because of their potent pro-resol- ving and anti-inflammatory actions verified in several in vivo disease models. Herein, we present the stereoselective synthesis and biological evaluations of 3-oxa-PD1n-3 DPA, a protectin D1 analog. Results from mouse models indicate that the mediators protectin D1, PD1n-3 DPA and the new analog 3-oxa- Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. PD1n-3 DPA all relieved streptozotocin-induced diabetic neuropathic pain at doses of 90 and 300 pmol, equivalent to 30 and 100 ng, respectively, following intrathecal (I.T.) injection. Of interest, at a low dose of only 30 pmol (10 ng; I.T.) only 3-oxa PD1n-3 DPA was able to alleviate neuropathic pain, directly compared Received 23rd October 2020, to vehicle controls. Moreover, using a chronic itch model of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), all three Accepted 2nd March 2021 compounds at 300 pmol (100 ng) showed a significant reduction in itching for several hours. -

Widespread Signals of Convergent Adaptation to High Altitude in Asia and America

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/002816; this version posted September 26, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Widespread signals of convergent adaptation to high altitude in Asia and America Matthieu Foll 1,2,3,*, Oscar E. Gaggiotti 4,5, Josephine T. Daub 1,2, Alexandra Vatsiou 5 and Laurent Excoffier 1,2 1 CMPG, Institute oF Ecology and Evolution, University oF Berne, Berne, 3012, Switzerland 2 Swiss Institute oF BioinFormatics, Lausanne, 1015, Switzerland 3 Present address: School oF LiFe Sciences, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, 1015, Switzerland 4 School oF Biology, Scottish Oceans Institute, University oF St Andrews, St Andrews, FiFe, KY16 8LB, UK 5 Laboratoire d'Ecologie Alpine (LECA), UMR 5553 CNRS-Université de Grenoble, Grenoble, France * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/002816; this version posted September 26, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Living at high-altitude is one oF the most diFFicult challenges that humans had to cope with during their evolution. Whereas several genomic studies have revealed some oF the genetic bases oF adaptations in Tibetan, Andean and Ethiopian populations, relatively little evidence oF convergent evolution to altitude in diFFerent continents has accumulated. -

Hydroxy-Very-Long-Chain Fatty Acids

The FASEB Journal • Research Communication Characterization of the human -oxidation pathway for -hydroxy-very-long-chain fatty acids Robert-Jan Sanders,* Rob Ofman,* Georges Dacremont,† Ronald J. A. Wanders,* and Stephan Kemp*,1 *Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases, Departments of Pediatrics/Emma Children’s Hospital and Clinical Chemistry, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; and †Department of Pediatrics, State University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium ABSTRACT Very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) trophy protein (ALDP), an ATP-binding cassette trans- have long been known to be degraded exclusively in porter protein located in the peroxisomal membrane peroxisomes via -oxidation. A defect in peroxisomal (3). One of the primary peroxisomal functions is -oxidation results in elevated levels of VLCFAs and is detoxification of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) associated with the most frequent inherited disorder of (Ͼ22 carbons) by chain shortening via -oxidation (4). the central nervous system white matter, X-linked adre- Although the exact role of ALDP remains elusive, it has noleukodystrophy. Recently, we demonstrated that VL- been implicated in the transport of VLCFA into peroxi- CFAs can also undergo -oxidation, which may provide somes (5, 6). In patients with X-ALD, the defect in an alternative route for the breakdown of VLCFAs. The ALDP results in decreased -oxidation of VLCFAs (7). -oxidation of VLCFA is initiated by CYP4F2 and As a result, VLCFAs accumulate in all tissues and CYP4F3B, which produce -hydroxy-VLCFAs. In this plasma (8). In brain, ALDP is expressed in all glial cell article, we characterized the enzymes involved in the types, including astrocytes, microglial cells, and oligo- formation of very-long-chain dicarboxylic acids from dendrocytes (9). -

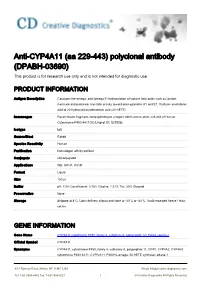

Anti-CYP4A11 (Aa 229-443) Polyclonal Antibody (DPABH-03690) This Product Is for Research Use Only and Is Not Intended for Diagnostic Use

Anti-CYP4A11 (aa 229-443) polyclonal antibody (DPABH-03690) This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic use. PRODUCT INFORMATION Antigen Description Catalyzes the omega- and (omega-1)-hydroxylation of various fatty acids such as laurate, myristate and palmitate. Has little activity toward prostaglandins A1 and E1. Oxidizes arachidonic acid to 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE). Immunogen Recombinant fragment, corresponding to a region within amino acids 229-443 of Human Cytochrome P450 4A11/22 (Uniprot ID: Q02928). Isotype IgG Source/Host Rabbit Species Reactivity Human Purification Immunogen affinity purified Conjugate Unconjugated Applications WB, IHC-P, ICC/IF Format Liquid Size 100 μl Buffer pH: 7.00; Constituents: 0.75% Glycine, 1.21% Tris, 20% Glycerol Preservative None Storage Shipped at 4°C. Upon delivery aliquot and store at -20°C or -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze / thaw cycles. GENE INFORMATION Gene Name CYP4A11 cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily A, polypeptide 12 [ Homo sapiens ] Official Symbol CYP4A11 Synonyms CYP4A11; cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily A, polypeptide 11; CP4Y; CYP4A2; CYP4AII; cytochrome P450 4A11; CYPIVA11; P450HL-omega; 20-HETE synthase; alkane-1 45-1 Ramsey Road, Shirley, NY 11967, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: 1-631-624-4882 Fax: 1-631-938-8221 1 © Creative Diagnostics All Rights Reserved monooxygenase; cytochrome P450HL-omega; cytochrome P-450HK-omega; fatty acid omega- hydroxylase; lauric acid omega-hydroxylase; 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthase; -

Title Page CYP4F3B Expression Is Associated with Differentiation Of

DMD Fast Forward. Published on July 21, 2011 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.110.036848 DMD ThisFast article Forward. has not been Published copyedited andon formatted.July 21, The 2011 final asversion doi:10.1124/dmd.110.036848 may differ from this version. DMD #36846 1 Title page CYP4F3B expression is associated with differentiation of HepaRG human hepatocytes and unaffected by fatty acid overload. Stéphanie Madec, Virginie Cerec, Emmanuelle Plée-Gautier, Joseph Antoun, Denise Glaise, Jean-Pierre Salaun, Christiane Guguen-Guillouzo and.Anne Corlu Downloaded from CNRS, UMR 7139, Station Biologique, BP74, 29682 Roscoff Cedex, France. (S.M., J-P. S.) dmd.aspetjournals.org Inserm, UMR–S 991, Liver Metabolisms and Cancer, Université de Rennes 1, CHU Rennes, avenue de la bataille Flandres-Dunkerque, 35033 Rennes, France. (V.C., D.G., C.G-G, A.C.) at ASPET Journals on October 1, 2021 Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Laboratoire de Biochimie, EA-948, Faculté de Médecine, CS 93837, 29238 Brest Cedex 3, France. (E. P-G., J.A., J-P. S) Copyright 2011 by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. DMD Fast Forward. Published on July 21, 2011 as DOI: 10.1124/dmd.110.036848 This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. DMD #36846 2 Running title page Running title: CYP4F3B and ω-hydroxylation of fatty acids in HepaRG cells Corresponding authors: Dr C. Guguen-Guillouzo and Dr A. Corlu, INSERM UMR-S 991, Hôpital Pontchaillou, 35033 Rennes cedex (France), Tel +33 (0)2 23 23 38 52, -

Role of 3-Hydroxy Fatty Acid-Induced Hepatic Lipotoxicity in Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Role of 3-Hydroxy Fatty Acid-Induced Hepatic Lipotoxicity in Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy Sathish Kumar Natarajan 1 ID and Jamal A. Ibdah 2,3,4,* 1 Department of Nutrition and Health Sciences, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68583-0806, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA 3 Department of Medical Pharmacology and Physiology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, USA 4 Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Medical Center, Columbia, MO 65201, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-573-882-7349; Fax: +1-573-884-4595 Received: 1 January 2018; Accepted: 16 January 2018; Published: 22 January 2018 Abstract: Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (AFLP), a catastrophic illness for both the mother and the unborn offspring, develops in the last trimester of pregnancy with significant maternal and perinatal mortality. AFLP is also recognized as an obstetric and medical emergency. Maternal AFLP is highly associated with a fetal homozygous mutation (1528G>C) in the gene that encodes for mitochondrial long-chain hydroxy acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (LCHAD). The mutation in LCHAD results in the accumulation of 3-hydroxy fatty acids, such as 3-hydroxy myristic acid, 3-hydroxy palmitic acid and 3-hydroxy dicarboxylic acid in the placenta, which are then shunted to the maternal circulation leading to the development of acute liver injury observed in patients with AFLP. In this review, we will discuss the mechanistic role of increased 3-hydroxy fatty acid in causing lipotoxicity to the liver and in inducing oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. -

Interpretive Guide for Fatty Acids

Interpretive Guide for Fatty Acids Name Potential Responses Metabolic Association Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Alpha Linolenic L Add flax and/or fish oil Essential fatty acid Eicosapentaenoic L Eicosanoid substrate Docosapentaenoic L Add fish oil Nerve membrane function Docosahexaenoic L Neurological development Omega-6 Polyunsaturated Linoleic L Add corn or black currant oil Essential fatty acid Gamma Linolenic L Add evening primrose oil Eicosanoid precursor Eicosadienoic Dihomogamma Linolenic L Add black currant oil Eicosanoid substrate Arachidonic H Reduce red meats Eicosanoid substrate Docosadienoic Docosatetraenoic H Weight control Increase in adipose tissue Omega-9 Polyunsaturated Mead (plasma only) H Add corn or black Essential fatty acid status Monounsaturated Myristoleic Palmitoleic Vaccenic Oleic H See comments Membrane fluidity 11-Eicosenoic Erucic L Add peanut oils Nerve membrane function Nervonic L Add fish or canola oil Neurological development Saturated Even-Numbered Capric Acid H Assure B3 adequacy Lauric H Peroxisomal oxidation Myristic H Palmitic H Reduce sat. fats; add niacin Cholesterogenic Stearic H Reduce sat. fats; add niacin Elevated triglycerides Arachidic H Check eicosanoid ratios Behenic H Δ6 desaturase inhibition Lignoceric H Consider rape or mustard seed oils Nerve membrane function Hexacosanoic H Saturated Odd-Numbered Pentadecanoic H Heptadecanoic H Nonadecanoic H Add B12 and/or carnitine Propionate accumulation Heneicosanoic H Omega oxidation Tricosanoic H Trans Isomers from Hydrogenated Oils Palmitelaidic H Eicosanoid interference Eliminate hydrogenated oils Total C18 Trans Isomers H Calculated Ratios LA/DGLA H Add black currant oil Δ6 desaturase, Zn deficiency EPA/DGLA H Add black currant oil L Add fish oil Eicosanoid imbalance AA/EPA (Omega-6/Omega-3) H Add fish oil Stearic/Oleic (RBC only) L See Comments Cancer Marker Triene/Tetraene Ratio (plasma only) H Add corn or black currant oil Essential fatty acid status ©2007 Metametrix, Inc.