Navigating the Erie Canal Through a Digital Exhibit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The End of the Line” DVD Press

"A fascinating bit of Rochester history." Jack Garner, Gannett Newspapers The End of the Line Rochester's Subway SPECIAL EDITION DVD Contact: Fred Armstrong Animatus Studio 34 Winthrop Street Rochester, NY 14607 Phone: (585) 232-1740 Fax: (585) 232-3949 Email: [email protected] Website: www.animatusstudio.com/subway Specs: 90 minutes, including extras NTSC/Color/Stereo Suggested Retail $29.95 For the first time on DVD "The End of the Line - Rochester's Subway" tells the little-known story of the rail line that operated in a former section of the Erie Canal from 1927 until its abandonment in 1956. Produced in 1994 by filmmakers Fredrick Armstrong and James P. Harte, the forty-five minute documentary recounts the tale of an American city's bumpy ride through the Twentieth Century, from the perspective of a little engine that could, but didn't. With 45 minutes of extras! • THREE ALL NEW FEATURETTES • THE ARCHIVE •The Steel Wheel A massive library of Experience a round trip ride on the subway photographs, artifacts as it existed in the 1950s. and artwork. •Prodigal Son - Rochester Car 60 Video of the subway's last surviving passenger • OUTTAKES car and an all new interview with one of the last motormen. • CLOSED CAPTIONING •Motherless Child - Remnants of the Subway A look at the subway as it exists today. • CHAPTER SELECTION Includes a "phantom run" through the abandoned Broad Street tunnel. • SUBWAY MAP INSERT The underground history of Rochester Billed as the story of the smallest city in America to build and abandon a subway, "The End of the Line - Rochester's Subway" originally aired on The History Channel and WXXI-TV, PBS Rochester. -

Monroebridgedata.Pdf

NY State Highway Bridge Data: August 31, 2021 Monroe County Year Date BIN Built or of Last Poor Region County Municipality Location Feature Carried Feature Crossed Owner Replaced Inspectio Status n 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4070890 RTE. 15 OVER CANAL 15 15 43031127 390I390I43031147 SB NYSDOT 1981 11/09/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4443310 JCT BARGE C + RTE 15A 15A 15A43041129 ERIE CANAL NYSDOT 2016 08/14/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1070900 JCT RTS I-390 & 15A 15A 15A43041228 390I390I43031142 NYSDOT 1981 12/08/2019 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1021650 0.8MI SE JCT RTS31+47 31 31 43033017 ALLEN CREEK NYSDOT 1964 07/22/2021 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1035220 1.0MI SE JCT RTS 96 + 441 96 96 43051088 ALLEN CREEK NYSDOT 1932 08/23/2019 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1044511 0.6 MI E JCT RTS 286 & 47 286 286 43011007 IRONDEQUOIT CREEK NYSDOT 1965 08/05/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1044512 0.6 MI E JCT RTS 286 & 47 286 286 43011007 IRONDEQUOIT CREEK NYSDOT 1965 07/23/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4443852 IN EAST BRIGHTON 390I390I43031129 ERIE CANAL NYSDOT 1981 09/21/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4443851 IN EAST BRIGHTON 390I390I43031132 ERIE CANAL NYSDOT 1981 09/21/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 1070940 .9 MI E JCT I390 & SH15A 390I390I43031133 590I590I43011002 NB NYSDOT 1981 09/22/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4443861 ROCHESTER OUTER LOOP N.B. 390I390I43031138 ERIE CANAL NYSDOT 1978 10/05/2020 N 04 Monroe Brighton (Town) 4443862 ROCHESTER OUTER LOOP S.B. -

Genesee Riverway Trail Bridge & Promenade

Genesee Riverway Trail Bridge & Promenade 2020 Local Bridge Conference City of Rochester, NY Lovely A. Warren, Mayor Rochester City Council NATIONAL FIRM. STRONG LOCAL CONNECTIONS. 1. Overview 2. Project Goals 3. Costs 4. Project Delivery 5. Structural Considerations 6. Unique Construction Features 7. Bridge Amenities 8. Historic Structure Interfaces 9. Learning Assessment 10. Questions & Answers AGENDA N City of Rochester 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW | Location “The Nathaniel” Pocket Promenade Park Dinosaur BBQ (former Lehigh Valley RR Station) Pedestrian Bridge Northern Gateway 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW | Components Ped Bridge Ribbon Cutting Project Ribbon Cutting Masterplan Interim Site Promenade Promenade Design Phase (TY Lin) Improvements (TY Lin) Construction Adjacent Private Development Building Building Building Design Re-Design Construction City-Developer Negotiations PROJECT OVERVIEW | Timeline Development is underway at the Leigh Valley Station with a 317 room, 18 story hotel...the old railroad station building is being retained for use as a restaurant… “a public walkway is planned adjacent to the river. - from the City of Rochester’s 1968 Comprehensive River Development” Plan 1. PROJECT OVERVIEW | Fulfilling a 50-year old vision N #1 Looking East Improve riverfront access & fill in missing #1 2. PROJECT GOALS Genesee Riverway Trail (GRT) segment Rundel Library Chiller System Raceway Discharge Restore integrity and functionality of the 2. PROJECT GOALS #2 Johnson & Seymour Raceway & Wall N 1.6 #3 acres Looking East Spur development of under-utilized, #3 2. PROJECT GOALS privately owned parcel 1 Looking Southwest 1 Dam Race Erie Canal 2 Dam FLASHBACK | Johnson & Seymour Raceway (1817) & Erie Canal (Mid 1800s) 1 2 1 2 Raceway FLASHBACK | Lehigh Valley Railroad (Circa 1917) 1 1 FLASHBACK | Rochester Subway (1927-1956) Dinosaur BBQ 1998 FLASHBACK | Site largely abandoned (1960-2010) N Court St. -

Historic Erie Canal Aqueduct & Broad Street Corridor

HISTORIC ERIE CANAL AQUEDUCT & BROAD STREET CORRIDOR MASTER PLAN MAY 2009 PREPARED FOR THE CITY OF ROCHESTER Copyright May 2009 Cooper Carry All rights reserved. Design: Cooper Carry 2 Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan HISTORIC ERIE CANAL AQUEDUCT & BROAD STREET CORRIDOR 1.0 MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 23 1.2 INTRODUCTION 27 1.3 PARTICIPANTS 33 2.1 SITE ANALYSIS/ RESEARCH 53 2.2 DESIGN PROCESS 57 2.3 HISTORIC PRECEDENT 59 2.4 MARKET CONDITIONS 67 2.5 DESIGN ALTERNATIVES 75 2.6 RECOMMENDATIONS 93 2.7 PHASING 101 2.8 INFRASTRUCTURE & UTILITIES 113 3.1 RESOURCES 115 3.2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan 3 A city... is the pulsating product of the human hand and mind, reflecting man’s history, his struggle for freedom, creativity and genius. - Charles Abrams VISION STATEMENT: “Celebrating the Genesee River and Erie Canal, create a vibrant, walkable mixed-use neighborhood as an international destination grounded in Rochester history connecting to greater city assets and neighborhoods and promoting flexible mass transit alternatives.” 4 Historic Erie Canal AQUedUct & Broad Street Corridor Master Plan 1.1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CREATING A NEW CANAL DISTRICT Recognizing the unrealized potential of the area, the City of the historic experience with open space and streetscape initiatives Rochester undertook a planning process to develop a master plan which coordinate with the milestones of the trail. for the Historic Erie Canal Aqueduct and adjoining Broad Street Corridor. The resulting Master Plan for the Historic Erie Canal Following the pathway of the original canal, this linear water Aqueduct and Broad Street Corridor represents a strategic new amenity creates a signature urban place drawing visitors, residents, beginning for this underutilized quarter of downtown Rochester. -

Back on the High Iron

NEXT MEETING: November 15 “Frostbite Ferroequinology” NEWSLETTER OF THE ROCHESTER & GENESEE VALLEY RAILROAD MUSEUM with Duncan Richards NOVEMBER 2012 VOL. 56 No. 3 COUNTRY COUSINS: Livonia, Avon & Lakeville #425 poses alongside RG&E 1941. Our 45-ton switcher was originally purchased by the LA&L in 1964 and their first locomotive. It was sold to RG&E in 1965. The 425 was LA&L’s first Alco road switcher puchase, the first of what would be many filling out the fleet of this successful regional railroad. On this day, 425 and 428 were teamed up to haul our Oct. 27 Rare Mileage Excursion from Lakeville to Henrietta and return. This was one of the photo stops orchestrated at Industry by our volunteers. PHOTO BY CHRIS HAUF Back on the High Iron After being idle for nearly eight years, it Another bit of exciting news is the was very exciting to see our excursion newly announced timeline for design and coaches take to the “high iron” once again! construction of our new inspection pit Many volunteers contributed countless inside the Restoration Building (See Page INSIDE hours to make our coaches ready for 3). Building this pit will allow us to better “prime time!” On October 27, your muse - maintain our railroad equipment and keep um hosted its first public excursion outside it in top running condition. This pit will Train Bulletin . 2 of the railroad since 2004. also benefit the New York Museum of Our special Rare-Mileage Excursion Transportation, and we are enjoying their covered the length of the Livonia, Avon & cooperation and assistance on this project. -

Click Here for a PDF of the Tour Program

A greeting from the tour chairperson Welcome to the 17th Annual Inside Downtown Tour! We’ve learned to be nimble during the yearlong pandemic and discovered that our virtual programs are reaching a whole new audience. Thank you for choosing to purchase an access ticket to the virtual tour. It will be available for your viewing pleasure from Friday night March 19th through Sunday night March 28th. Our 2020 Inside Downtown tour, highlighting our downtown core, this year showcases the evolution of downtown urban living for more than 100 years. Rochester and its downtown neighborhoods are historically significant through its culture, community as well as its brick and mortar. Each historic structure speaks to cultures and citizens that have passed through - with their accomplishments and setbacks; children who have grown to effect change whether near or far. The remaining gems are structures with good bones...all tell a story; some have new chapters some are waiting to begin anew. We also honor new construction that shows a connection to the environment, sensitively designed. Those that can be saved must be so for in that effort to reconnect, we too, are rehabilitated and reinvigorated. The Landmark Society works tirelessly to ensure this higher purpose. As community members, we often hear about urban efforts to repurpose, rehabilitate, and create ways to reuse historic buildings. Through this video, you will experience these iconic structures that are now vibrant with life. You will see why developers, residents and businesses have chosen to commit to Rochester’s centre city. What’s old is new, infused with a sense of community building and purpose. -

Rochester's Landmark Buildings

Rochester’s Landmark Buildings (and their stories) by Tom Fortunato A presentation for the Rochester Philatelic Association, 2020 The City of Rochester, NY has a rich architectural history seen through its buildings of today and images of the past. Iconic companies and wealthy businessmen often built skyscrapers downtown that took their name, including Kodak, Xerox and Bausch & Lomb. The buildings are still here while their original occupants are gone. Here are seven classic structures still on the city skyline you may not be so familiar with. Next time you drive by you’ll know more about them. This brief presentation uses advertising covers, postcards and photos to make the reader aware of what was and still is in the Flower City. Enjoy! Let’s start out with an easy quiz… How many of these Rochester sites can you identify from 1937? Look at Answers each appear letter on the and next identify slide. the They are landmark all still shown. around! How did you do? R Eastman S Cumberland Theater Post Office O U of R T Driving Park Library Bridge C Highland E Charlotte Park Bath House H Public R Auditorium Library Theater E Veteran’s Memorial Bridge Buildings in this presentation include: West Main St Area • Duffy-Powers Building • Powers Building/Hotel • German Insurance Company Building • Ellwanger and Barry Building East Main St Area • Wilder Building • Granite Building • Sibley Triangle Building These classic buildings are all in central downtown, most around the “Four Corners” intersection of Main and State streets. 100 Acre Plot Tour Look for web links like this throughout the presentation to learn more about the buildings. -

Central City Online Tour.Pub

About This Tour This tour is a 4/5th of a mile loop that crosses and parallels the Genesee River. This route mixes historic buildings with contemporary office and hotel buildings. For tour maps, see last pages. Rochester city streets on a whole are pedestrian, wheelchair and stroller friendly. In particular, for those taking this tour it is possible The Landmark Society of Western New York to stay exclusively on city sidewalks, with only a few driveways and alleys to cross. 133 South Fitzhugh Street Rochester NY 14608 Historic Highlights These are 24 sites along the tour; including 2 www.landmarksociety.org districts, 3 bridges and 13 buildings listed in the National Register of Historic Places. A most appropriate place to start a tour of Rochester is the south side of the Main Street Bridge (1857) (1). This limestone bridge is the fourth on this site; the first one, of wood, was finished in 1812. From the 1850s to the mid-1960s, the Main Street Bridge was actually lined with a variety of commercial buildings, making the river almost invisible from the bridge. The Genesee River, which bisects downtown and is directly involved with this city’s founding and growth, flows north to Lake Ontario. It is one of the few in the country with this natural characteristic. Used as a source of waterpower since the early 1800s, the river was of utmost importance to Colonel Nathaniel Rochester, a Maryland pioneer who developed a 100-acre tract on the Genesee west bank. This settlement formed the nucleus of the village of Rochesterville, which was chartered in 1817 and eventually grew to become the city of Rochester by 1834. -

Rochester Transit (1982 – 1983)

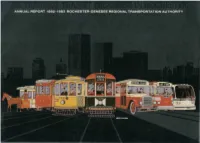

ROCHESTER-GENESEE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY COMMISSIONERS Andrew F. Caverly William E. Hanson James Lloyd Elizabeth H. Knight Monroe County Genesee County City of Rochester Monroe County Chairman Vice Chairman Secretary Assistant Secretary Ronald Baug Don W. Cook Harold A. Shay Thomas F. Toole Robert D.Waterman Monroe County Monroe County Livingston County City of Rochester Wayne County CHAIRMAN- EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR'S STATEMENT ~----------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------~ Public transportation has been an important is again increasing as transit continues to national attention as it continues to grow. The key to the growth of the United States, and become a more rational economic choice. Livingston Area Transit Service serves the needs particularly to the development of its cities and The Rochester-Genesee Regional Transpor- of a large number of senior citizens in three com- towns. Our own city of Rochester has a tation Authority is proud of the level of service munities and their surrounding areas, and The fascinating history of developing transit which provided throughout a four-county regional area. Batavia Bus Service provides dial-a-bus service has responded to the needs of our growing RTS, for instance, offers better, more frequent to the residents of Batavia in Genesee County. metropolitan area. service than that provided in most cities Without public transit, an important element Now, as we pause to celebrate the Sesqui- comparable in size to Rochester, and many that in the strong flow of our regional community's centennial of the City of Rochester, it is are larger. life blood would no longer be available, and the appropriate that we devote this Annual Report Since its creation in 1969, R-GRTA has work- halt of transit service would contribute to the to a review of the proud history of transit ed hard to expand and develop transit services diminished attractiveness of the area as a place in Rochester. -

ROCHESTER Hislory Sources of Energy in Rochester's History

ROCHESTER HISlORY Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck, Editor Vol. XLVI July and October, 1984 Nos. 3 and 4 Sources of Energy In Rochester's History by Rod Bailey ~4.33 trillion BTU petroleum !!ii [;f uranium 0 433 mi] I iac 6III e•r eers9n gas m• 0 10,000 population hydro D coal a wood ml ff'Ambl 5. 73 tri 11 ion BTU f 180 ml 11 Ion BTU per person c:J 32.000 population ROCHESTER'S ENERGY HISTORY CHART by Rod Bailey, RIT lfAJ:·\·,'5:\"".~:';-~.I 9. 23 tri 11 ion BTU per person :;;o"' r----, L---J 69 mi 11 ion BTU per person 133,000 population 39.2 trl It ion BTU ._____ _,J 122 million BTU per person 320,000 population '/lllllil/l lil/lll@i,11111 52,9 trillion BTU 220 ml 11 ion BTU per person 240,000 popul,tion ROCHESTER HISlORY, published quarterly by the Rochester Public Library, distrib uted free at the Library, by mail $1.00 per year. Address correspondence to City Historian, Rochester Public Library, 115 South Ave., Rochester, NY 14604. ©ROCHESTER PUBLIC L1BRARY1985 US ISSN 0035-7413 2 Nine flour mllla - operating In 1aeo along the eNt bank of the a..-RI-. ThNe mlNa ,_ the Main Falla-: 1) The Ge,,._ Falla MIiia; 2) The Cotton Fectory; 3) Achllln' Custom MIiia; 4) Rewr9 MIiia; 5) Glanlte MIiia; I) Phoenix MIiia; 7) New 'lbfll Miila; 8) Rlchardaon'• MIiia; 9) Sllu 0. Smith'• MIiia. the -at aide mllla a111 on Brown'• Race. (Photo from J.H. French'I O.zelfff' of The Si.le of N- Yorlr, 1850). -

Historic Resources Survey 2000 a Reportonthebuiltenvironmentof1936-1950 Copyright ©

Historic Resources Survey 2000 A Report on the Built Environment of 1936-1950 Copyright © 2000 - City of Rochester, New York H R S G Overview Historic Resource Survey of the Built Environment, 1936-1950 The City of Rochester conducted this Historic Resources Survey in cooperation with New York State Office of Parks Recreation and Historic Preservation. The survey commenced in the summer of 1998 and concluded in April, 2000. Over 6,000 buildings were investigated in a search for structures eligible for nomination to the State and National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). Two City of Rochester databases were used to identify properties for inclusion in the search: The Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and the Building Information System (BIS). From this large group, two districts and fifteen individual properties are recommended for State or National Register listing. The nominated structures range from residential to industrial, and include a gas station and a television studio. Each recommended resource represents the best example of its building type existing in Rochester today. The selected districts and resources display better than average architectural design and integrity, and reflect specific architectural, development or historic trends seen in Rochester. The organizational structure of the survey places buildings in thematic groups which identify a structure’s primary function. There are ten thematic groups: Architects and Architecture Industrial Development Commercial Development Parks and Recreation Cultural/Societal Religion -

Course Listings for Arts, Sciences and Engineering 2015-2017 Arts Sciences and Engineering Abbreviations and Prefixes 1

University of Rochester Course Listings for Arts, Sciences and Engineering 2015-2017 Arts Sciences and Engineering Abbreviations and Prefixes 1 AAS African and African-American Studies EPD Epidemiology ACC Accounting FEC Financial Economics AH Art History FIN Finance AME Audio and Music Engineering FR French AMS American Studies FMS Film and Media Studies ANT Anthropology GBA General Business Administration ARA Arabic GER German ASL American Sign Language HBS Health, Behavior, and Society AST Astronomy HEB Hebrew ATH Archeology, Technology, and Historical Structures HIS History BCD Biological Sciences: Cell and Developmental Biology HLP Health Policy BCH Biological Sciences: Biochemistry HLS Health and Society BCS Brain and Cognitive Sciences IPA Interdepartmental, Arts and Sciences BEB Biological Sciences: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology IR International Relations BET Bioethics IT Italian BIO Biology JPN Japanese BMB Biological Sciences: Microbiology JST Judaic Studies BME Biomedical Engineering KOR Korean BMG Biological Sciences: Molecular Genetics LAT Latin BSB Business LAW Business Law CAS Arts and Sciences, the College LIN Linguistics CGR Classic Greek LTS Literary Translation Studies CHE Chemical Engineering MBI Microbiology & Immunology CHI Chinese ME Mechanical Engineering CHM Chemistry MKT Marketing CIS Computers and Information Systems MSC Materials Science CLA Classical Studies MTH Mathematics CLT Comparative Literature MUR Music CSC Computer Science NAV Naval Science CSP Clinical and Social Sciences in Psychology NSC Neuroscience