Technical Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact of Biological Control on Two Knapweed Species in British Columbia

Impact of Biological Control on Two Knapweed Research Report Species in British Columbia Don Gayton, FORREX & Val Miller, B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations Abstract Diffuse and spotted knapweed ( Centaurea diffusa Lam and C. stoebe L.) are two closely re - lated invasives found in many parts of British Columbia’s Southern Interior, causing sub - stantial economic losses in rangelands. Beginning in 1970, the provincial government initiated a long-term biological control effort against the knapweeds, introducing 10 dif - ferent insect agents from 1970 to 1987. In an effort to evaluate the efficacy of the program, archival (1983–2008) data was amassed from 19 vegetation monitoring sites that contained knapweed. In 2010, these sites were relocated and re-monitored and cover values were an - alyzed. Diffuse knapweed showed significant declines at 14 of 15 sites; spotted knapweed declined at three of four sites. Possible alternative explanations for the decline are dis - cussed. Evidence strongly points to a suite of biocontrol agents (seed feeders and root feed - ers) as the primary drivers of knapweed decline in British Columbia’s Southern Interior. KEYWORDS : biological control; British Columbia; Centaurea ; knapweed; monitoring Introduction iffuse knapweed ( Centaurea diffusa Lam.) and spotted knapweed ( Centaurea stoebe L.) are two introduced, closely related invasive forbs. These species are most com - Dmon in the northwestern United States and in western Canada. Centaurea stoebe (also referred to as C. maculosa Lam. and C. biebersteinii DC) is particularly widespread, reported in 45 US states and all provinces of Canada (Marshall 2004; Zouhar 2001). The drought-tolerant C. diffusa has an altitudinal range of 150–900 m, whereas C. -

Centaurea Stoebe Ssp. Micranthos

Species: Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/cenmac/all.html SPECIES: Centaurea maculosa Introductory Distribution and occurrence Management Considerations Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Centaurea maculosa AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Zouhar, Kris. 2001. Centaurea maculosa. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: CENMAC SYNONYMS: Centaurea biebersteinii DC. [82] Centaurea stoebe L. ssp. micranthos (Gugler) Hayek [137] NRCS PLANT CODE [212]: CEBI2 1 of 58 9/24/2007 4:04 PM Species: Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/cenmac/all.html COMMON NAMES: spotted knapweed TAXONOMY: The scientific name for spotted knapweed is Centaurea maculosa Lam. (Asteraceae) [45,67,217,233]. Oschmann [137] suggests that in North America, the name Centaurea maculosa has been misapplied to Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos. The taxonomy of spotted knapweed is discussed in Ochsmann [137] and on the Centaurea website. Oschsmann [136] also cites evidence of hybridization between spotted and diffuse knapweed (Centaurea diffusa) in at least 7 U.S. states. The hybrid is named Centaurea × psammogena Gayer. LIFE FORM: Forb FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: No special status OTHER STATUS: Spotted knapweed has been declared a noxious or restricted weed in at least 15 states in the U.S. and 4 Canadian provinces [213]. -

(Centaurea Stoebe Ssp. Micranthos) Biological Control Insects in Michigan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Valparaiso University The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 47 Numbers 3 & 4 - Fall/Winter 2014 Numbers 3 & Article 3 4 - Fall/Winter 2014 October 2014 Establishment, Impacts, and Current Range of Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea Stoebe Ssp. Micranthos) Biological Control Insects in Michigan B. D. Carson Michigan State University C. A. Bahlai Missouri State University D. A. Landis Michigan State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Carson, B. D.; Bahlai, C. A.; and Landis, D. A. 2014. "Establishment, Impacts, and Current Range of Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea Stoebe Ssp. Micranthos) Biological Control Insects in Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 47 (2) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol47/iss2/3 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Carson et al.: Establishment, Impacts, and Current Range of Spotted Knapweed (<i 2014 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 129 Establishment, Impacts, and Current Range of Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos) Biological Control Insects in Michigan B. D. Carson1, C. A. Bahlai1, and D. A. Landis1* Abstract Centaurea stoebe L. ssp. micranthos (Gugler) Hayek (spotted knapweed) is an invasive plant that has been the target of classical biological control in North America for more than four decades. -

Centaurea Stoebe)

Chapter 11 Sustainable Control of Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) D.G. Knochel and T.R. Seastedt Abstract Spotted knapweed is native to Eastern Europe, with a locally scarce but widespread distribution from the Mediterranean to the eastern region of Russia. The plant is one of over a dozen Centaurea species that were accidentally introduced into North America and now is found in over 1 million ha of rangeland in the USA and Canada. Land managers spend millions of dollars annually in an attempt to control spotted knapweed and recover lost forage production, and meanwhile the plant perse- veres as a detriment to native biodiversity and soil stability. These ecological concerns have motivated intense scientific inquiry in an attempt to understand the important fac- tors explaining the unusual dominance of this species. Substantial uncertainty remains about cause–effect relationships of plant dominance, and sustainable methods to control the plant remain largely unidentified or controversial. Here, we attempt to resolve some of the controversies surrounding spotted knapweed’s ability to dominate invaded com- munities, and focus on what we believe is a sustainable approach to the management of this species in grasslands, rangelands, and forests. Application of both cultural and bio- logical control tools, particularly the concurrent use of foliage, seed, and root feeding insects, is believed sufficient to decrease densities of spotted knapweed in most areas to levels where the species is no longer a significant ecological or economic concern. Keywords Biological control • Biological invasions • Centaurea stoebe L. ssp micranthos • Centaurea maculosa • Knapweed • Sustainable management 11.1 Introduction Knapweeds and yellow starthistle, plants belonging to the genus Centaurea and the closely related genus Acroptilon, are members of the Asteraceae that were acciden- tally introduced into North America from Eurasia over a century ago. -

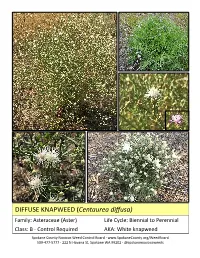

DIFFUSE KNAPWEED (Centaurea Diffusa)

DIFFUSE KNAPWEED (Centaurea diffusa) Family: Asteraceae (Aster) Life Cycle: Biennial to Perennial Class: B - Control Required AKA: White knapweed Spokane County Noxious Weed Control Board · www.SpokaneCounty.org/WeedBoard 509-477-5777 · 222 N Havana St, Spokane WA 99202 · @spokanenoxiousweeds DIFFUSE KNAPWEED DESCRIPTION • Most flowers white, but may be light purple Growth Traits: Biennial to short-lived perennial; bushy plant growing to three and a half feet tall. Long taproot. • 20% to 50% of plants break from root crown Begins as basal rosette, then develops a main stem that and become tumbleweeds, spreading seeds branches extensively. Heavy branching makes a bushy, • May hybridize with spotted knapweed rounded plant. Knapweeds are allelopathic; they exude chemicals that inhibit the growth of nearby plants • Native to eastern Europe and western Asia creating an environment in which they can spread and CONTROL METHODS form monocultures more rapidly. Mechanical: Hand pulling feasible for small Leaves and Stems: Leaves and stems covered in short populations; ensure roots are removed and pull coarse hairs, giving plant gray-green appearance. new plants multiple times through season. Leaves and stems feel somewhat coarse. Basal leaves are deeply lobed. Upper leaves are linear and not Mowing at late bud to early flower stage, two to lobed. Stems branch extensively. four times per season, can reduce seed production. Mowing can encourage plants to Flowers: Blooms June - September. Flowers typically bloom and set seed at mower blade height. white, but may be pale purple. Flower bracts fringed Regular cultivation will control knapweed; always with spines, and end in a spine that extends away from clean equipment before removing from infested the flowerhead. -

Reference Plant List

APPENDIX J NATIVE & INVASIVE PLANT LIST The following tables capture the referenced plants, native and invasive species, found throughout this document. The Wildlife Action Plan Team elected to only use common names for plants to improve the readability, particular for the general reader. However, common names can create confusion for a variety of reasons. Common names can change from region-to-region; one common name can refer to more than one species; and common names have a way of changing over time. For example, there are two widespread species of greasewood in Nevada, and numerous species of sagebrush. In everyday conversation generic common names usually work well. But if you are considering management activities, landscape restoration or the habitat needs of a particular wildlife species, the need to differentiate between plant species and even subspecies suddenly takes on critical importance. This appendix provides the reader with a cross reference between the common plant names used in this document’s text, and the scientific names that link common names to the precise species to which writers referenced. With regards to invasive plants, all species listed under the Nevada Revised Statute 555 (NRS 555) as a “Noxious Weed” will be notated, within the larger table, as such. A noxious weed is a plant that has been designated by the state as a “species of plant which is, or is likely to be, detrimental or destructive and difficult to control or eradicate” (NRS 555.05). To assist the reader, we also included a separate table detailing the noxious weeds, category level (A, B, or C), and the typical habitats that these species invade. -

Montana Knapweeds

Biology, Ecology and Management of Montana Knapweeds EB0204 May 2011 Celestine Duncan, Consultant, Weed Management Services, Helena, MT Jim Story, Research Professor, retired, MSU Western Ag Research Center, Corvallis, MT Roger Sheley, former MSU Extension Weed Specialist, Bozeman, MT revised by Hilary Parkinson, MSU Research Associate, and Jane Mangold, MSU Extension Invasive Plant Specialist Table of Contents Plant Biology . 3 SpeedyWeed ID . 5 Ecology . 4 Habitat . 4 Spread and Establishment Potential . 6 Damage Potential . 7 Origins, Current Status and Distribution . 8 Management Alternatives . 8 Prevention . 8 Mechanical Control . .9 Cultural Control . .10 Biological Control . .11 Chemical Control . .14 Integrated Weed Management (IWM) . 16 Additional Resources . 16 References . 17 Acknowledgements . .19 COVER PHOTOS large - spotted knapweed by Marisa Williams, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, bugwood.org top inset - diffuse knapweed by Cindy Roche, bugwood.org bottom inset - Russain knapweed by Steve Dewey, Utah State University, bugwood.org Any mention of products in this publication does not constitute a recommendation by Montana State University Extension. It is a violation of Federal law to use herbicides in a manner inconsistent with their labeling. Copyright © 2011 MSU Extension The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Montana State University and Montana State University Extension prohibit discrimination in all of their programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital and family status. Issued in furtherance of cooperative extension work in agriculture and home economics, acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Douglas L. Steele, Vice President of External Relations and Director of Extension, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717. -

Diffuse Knapweed Centaurea Diffusa

Diffuse knapweed Other common names: White knapweed, spreading USDA symbol: CEDI3 Centaurea diffusa knapweed, tumble knapweed ODA rating: B Distribution in Oregon: Although widely, diffuse knapweed has limited distribution in Oregon with the northeastern and central areas having the heaviest infestation. Introduction: Diffuse is a member of a large genus of over 400 species, most originating in the Mediterranean region. Diffuse knapweed was first introduced to the Pacific Northwest at the turn of the century as a contaminant in alfalfa seed imported from Turkestan, Turkmenistan or hybrid alfalfa seed from Germany. Description: Diffuse knapweed is a biennial that flowers from midsummer to fall. It grows to 3 feet tall. It is a single-stemmed plant with numerous lateral branches. Flowers are white to rose, sometimes purplish. Flower heads are slender with pointed, fringed bracts and grows out of urn-shaped heads carried as the tips of the many branches. It spreads by seed, aided by the tumbling of windblown mature plants. A single plant can produce approximately 18,000 seeds. Impacts: Diffuse knapweed will form dense stands on any open ground, excluding more desirable forage species. Once established, the necessary extensive control measures are often more expensive than the income potential of the land. It grows under a wide range of conditions, such as riparian areas, sandy river shores, gravel banks, rock outcrops, rangelands and roadsides. There are possible health hazards from absorbing plant juice through bare hand pulling of plants. It is recommended that gloves be worn while handling plants. Diffuse knapweed also supports small mites that bite humans and cause skin irritation Biological controls: Biocontrol agents include several seed feeding flies and weevils, and a root-boring beetle. -

Complete Hanford Reach National Monument Weed Book

Hanford Reach National Monument / Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Noxious Weeds Field Guide Prepared for educational and field use by Staff of the Hanford Reach National Monument/Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge. Hanford Reach National Monument Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge Noxious Weed Field Guide Table of contents: Yellow Starthistle Centaurea solistitialis L. Rush Skeletonweed Chondrilla juncea L. Salt Cedar Tamarix ramosissima Ledeb. Purple Loosestrife Lythrum salicaria L. Puncturevine, Bullhorns, Goathead, Sandbur Tribulus terrestris L. Russian Knapweed Centaurea repens L. Perennial Pepperweed, Hoary Cress and related whitetops Lepidim latifolium L., Cardaria draba (L.) Desv., C. pubescens (C.A. Meg Jarmolenko), and C. chalapensis L. Diffuse Knapweed, Tumble Knapweed Centaurea diffusa Lam. Spotted Knapweed Centaurea biebersteinii DC. = Centaurea maculosa Lam. Hairy Willow-herb Epilobium hirsutum Dalmatian Toadflax Linaria dalmatica L. Camelthorn Alhagi Pseudalhagi Bieb. Canada Thistle Cirsium arvense L. Scotch Thistle Onopordum acanthium L. What is a Noxious Weed? Weeds are plants that interfere with management objectives for a given area of land at a given point in time. Noxious weeds are invasive non-native plants that are aggressive, competitive, highly destructive or difficult to control. “Noxious weed” is also a legal term: the Washington State Noxious Weed List is a regulatory list identifying plants that, by law, must be controlled. The Problem of Noxious Weeds: Noxious weeds are fierce competitors - able to invade and dominate sites very quickly. Many of these weeds are poisonous or can cause other types of physical damage to wildlife, livestock, and humans. Because most of these are non-native, they are able to outcompete the local native plants. -

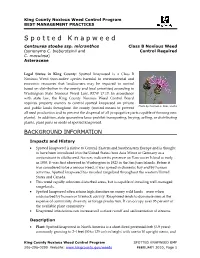

King County Best Management Practices for Spotted Knapweed

King County Noxious Weed Control Program BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Spotted Knapweed Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos Class B Noxious Weed (synonyms C. biebersteinii and Control Required C. maculosa) Asteraceae Legal Status in King County: Spotted knapweed is a Class B Noxious Weed (non‐native species harmful to environmental and economic resources that landowners may be required to control based on distribution in the county and local priorities) according to Washington State Noxious Weed Law, RCW 17.10. In accordance with state law, the King County Noxious Weed Control Board requires property owners to control spotted knapweed on private and public lands throughout the county (control means to prevent Photo by Norman E. Rees, USDA all seed production and to prevent the dispersal of all propagative parts capable of forming new plants). In addition, state quarantine laws prohibit transporting, buying, selling, or distributing plants, plant parts or seeds of spotted knapweed. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Impacts and History Spotted knapweed is native to Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe and is thought to have been introduced into the United States from Asia Minor or Germany as a contaminant in alfalfa seed. Sources indicate its presence on Vancouver Island as early as 1893. It was first observed in Washington in 1923 in the San Juan Islands. Before it was considered to be a serious weed, it was spread in domestic hay and by human activities. Spotted knapweed has invaded rangeland throughout the western United States and Canada. This weed rapidly colonizes disturbed areas, but is capable of invading well‐managed rangelands. Spotted knapweed often attains high densities on sunny wild lands—even when undisturbed by human or livestock activity. -

SPOTTED KNAPWEED (Centaurea Biebersteinii)

NOXIOUS WEEDS IN CLALLAM COUNTY SPOTTED KNAPWEED (Centaurea biebersteinii) Spotted knapweed grows 8 to 40 inches tall. The upright stems are somewhat branched, mainly in the upper half. The leaves at the base of the plant are about four inches long and divided into lobes. The blue-gray leaves become smaller higher up the stem. The flower heads are solitary at the ends of clustered branches. The flowers, which bloom from June to October, are pink to purple, sometimes white. The bracts, which occur at the base of the flower head, have a spinelike fringe on the upper edge and at the tip; the center “spine” is shorter than the others. The bracts also usually have a black spot on the tip but this may be lacking on white-flowered plants. If it is missing, the shorter central “spine” is usually a good ID feature. Bracts are modified leaves, usually near a flower. In most knapweed species the bracts form a cup-like structure that supports the flower head. Some knapweeds are similar looking and differences in the bracts can be an important way of distinguishing species. Threats: · Spotted knapweed is an aggressive and invasive species that invades pastures and meadows, displacing forage plants but having little value as forage itself. · It reduces the water storage capacity of soil and increases erosion. Spotted knapweed is a Class B designate weed in Clallam County. Control is required county-wide. Look-a-likes: At least six other knapweed species occur in Clallam County; all of them could be mistaken for spotted knapweed. -

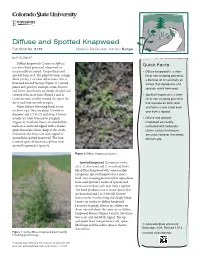

Diffuse and Spotted Knapweed Fact Sheet No

Diffuse and Spotted Knapweed Fact Sheet No. 3.110 Natural Resources Series|Range by K.G. Beck* Diffuse knapweed (Centaurea diffusa) Quick Facts is a short-lived perennial, a biennial, or occasionally an annual. It reproduces and • Diffuse knapweed is a short- spreads from seed. The plant develops a single lived, non-creeping perennial, shoot (stem), 1 to 2 feet tall or more, that is a biennial, or occasionally an branched toward the top (Figure 1). Grazed annual that reproduces and plants may produce multiple stems. Rosette spreads solely from seed. and lower shoot leaves are deeply divided and covered with short hairs (Figure 2 and 3). • Spotted knapweed is a short- Leaves become smaller toward the top of the lived, non-creeping perennial shoot and have smooth margins. that reproduces from seed Many solitary flowering heads occur and forms a new shoot each on shoot tips. They are about 1/8 inch in year from a taproot. diameter and 1/2 to 2/3 inch long. Flowers usually are white but may be purplish • Diffuse and spotted (Figure 4). Involucre bracts are divided like knapweed are readily teeth on a comb and tipped with a slender controlled with herbicides. spine that makes them sharp to the touch. Unless cultural techniques Sometimes the bracts are dark-tipped or are used, however, the weeds spotted like spotted knapweed. The long will reinvade. terminal spine differentiates diffuse from spotted knapweed (Figure 6). Figure 2: Diffuse knapweed rosettes. Spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe; a.k.a., C. biersteinii and C. maculosa) looks like diffuse knapweed with some notable exceptions.