Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scary Poppins Returns! Doctor Who: the Eighth Doctor, Liv and Helen Are Back on Earth, but This Time There’S No Escape…

ISSUE: 136 • JUNE 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM SCARY POPPINS RETURNS! DOCTOR WHO: THE EIGHTH DOCTOR, LIV AND HELEN ARE BACK ON EARTH, BUT THIS TIME THERE’S NO ESCAPE… DOCTOR WHO ROBOTS THE KALDORAN AUTOMATONS RETURN BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Torchwood, Dark Shadows, @BIGFINISH Blake’s 7, The Avengers, THEBIGFINISH The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain BIGFINISHPROD Scarlet and Survivors, as BIG-FINISH well as classics such as HG BIGFINISHPROD Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summer eld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH EDITORIAL WE’RE CURRENTLY in very COMING SOON interesting times, aren’t we? The COVID-19 pandemic has changed all our lives in recent ABBY AND ZARA months, with lockdown becoming a part of our everyday routine. -

Toys for the Collector 27Th & 28Th October 2020 at 10.00 ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Viewing: by Appointment Only

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Toys for the Collector 27th & 28th October 2020 at 10.00 ONLINE ONLY AUCTION Viewing: by appointment only Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Fine Diecasts Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Graham Bilbe Adrian Little Toys Trains Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 1. A Pre-War Dinky Toys 48 Petrol 8. Pre-War Dinky Toy Military 17. Dinky Toy Cars, 30d Vauxhall, 36b 25. Dinky Toy Cars, including 40a 34. Dinky Toys 38b Sunbeam 43. Dinky Toys 370 Dragster Set, Station, tinplate construction with ‘Filling Aircraft, 62h Hawker Hurricane (4), 62e Bentley, 36c Humber Vogue, 36d Rover, Riley Saloon, 40g Morris Oxford, 40d Talbot Sports, two examples, first red 109 Gerry Anderson’s The Secret Service & Service Station’ roof sign, green roof Vickers-Supermarine Spitfire (3), 62d 36e British Salmson, 30b Rolls-Royce, 40a Austin Devon, 40e Standard Vanguard, body, maroon tonneau, black ridged Gabriel Model T Ford, 290 S R N 6 and base, G-VG Blenheim Bomber, all in camouflage, 62a Riley (2), 40b Triumph, 39a Packard, P-VG Austin Atlantic and five others, with hubs, second early issue, grey body, dark Hovercraft, in original boxes, VG-E, boxes £80-120 Spitfire, 60p Gloster Gladiator (2), P-F, (10) Schuco Micro Racer 1043/1 Mercedes SSK grey tonneau, black smooth hubs, solid G-VG (3) most with fatigue damage or missing parts £80-120 and white metal kit built MG, F-VG, some steering wheel, VG-E, grey example with £60-80 2. -

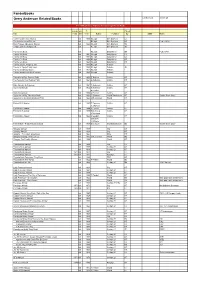

Fanderbooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08

FanderBooks Gerry Anderson Related Books List Revised: 27-Oct-08 Pre-1990 UK Gerry Anderson Annuals/Large Format Books Annual p/b © Check Title Year† h/b Year Author Publisher By ISBN ** Notes Twizzle's Adventure Stories h/b 1958 R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT The Adventures of Twizzle h/b R.Leigh Birn Brothers AT Publ. 1959? More Twizzle Adventure Stories h/b 1960 R.Leigh Birn Brothers TN Twizzle and the Hungry Cat p/b R.leigh Birn Brothers JB Torchy Gift Book h/b R.Leigh Daily Mirror SB Publ. 1960 Torchy Gift Book h/b 1961 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1962 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1963 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy Gift Book h/b 1964 R.Leigh Daily Mirror AT Torchy and the Magic Beam h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy in Topsy-Turvy Land h/b 1960 R.Leigh Pelham JB Torchy and Bossy Boots h/b 1961 R.Leigh Pelham - Torchy and his Two Best Friends h/b 1962 R.Leigh Pelham - Television's Four Feather Falls h/b 1960 S.Thamm Collins AT Tex Tucker's Four Feather Falls h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Mike Mercury in Supercar h/b 1961 S.Anderson Collins AT Supercar Annual h/b 1962 S.Anderson Collins AT & E.Eden Supercar Annual h/b 1963 A.Fennell Collins AT Supercar - A Big Television Book h/b 1962 G.Sherman World Distributors AT Golden Book Story Supercar on the Black Diamond Trail h/b 1965 J.W.Jennison World AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1963 D.Spooner Collins AT & J.Hynam Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1964 A.Fennell Collins AT Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1965 D.Motton & Collins AT J.Dennison Fireball XL5 Annual h/b 1966 S.Goodall, -

Catalogue 876.Pdf

FLECK WAY, THORNABY, STOCKTON-ON-TEES TS17 9JZ Telephone: 0044 (0)1642 750616 Fax: 0044 (0)1642 769478 e-mail: [email protected] www.vectis.co.uk Oxford Office - Unit 5A, West End Industrial Estate, Witney, Oxon OX28 1UB Telephone: 0044 (0)1993 709424 TV & FILM RELATED SALE Thursday 29th April 2021 Auction Commences at 10.00am Bidding can be made using the following methods: Commission bids: Postal/Fax: Telephone bidding and Internet bidding. You can leave proxy bids at www.vectis.co.uk or bid live online with www.vectis.co.uk & www.invaluable.com If you intend to bid by telephone please contact the office for further information on 0044 (0)1642 750616 Forthcoming Room Sales at Vectis Auctions Wednesday 12th May 2021 - Diecast Sale Thursday 13th May 2021 - Diecast Sale Wednesday 19th May 2021 - Military, Civilian Figures, Equipment & Accessories Sale Thursday 20th May 2021 - General Toy Sale Wednesday 26th May 2021 - Matchbox Sale Thursday 27th May 2021 - Matchbox Sale Friday 28th May 2021 - Model Train Sale Dates are correct at time of print but are subject to change - please check www.vectis.co.uk for updates Managing Director . .Vicky Weall Auctioneers . .Debbie Cockerill, Julian Royse & Jo McDonald Cataloguers . .Nick Dykes & Kathy Taylor Photography . .Paul Beverley & Andrew Wilson Data Input . Nick Dykes & Kathy Taylor Layout & Design . .Simon Smith A subsidiary of The Hambleton Group Ltd - VAT Reg No. 647 5663 03 www.vectis.co.uk Contents Thursday 29th April 2021 TV & Film ........................................................................................................................................Lots 4001 – 4323 The Beatles Collection.....................................................................................................................Lots 4324 – 4357 TV & Film ........................................................................................................................................Lots 4358 – 4578 Live Internet Bidding All Lots in the sales can be viewed via our website on www.vectis.co.uk. -

Recursos Electrónicos HIS-212

La aventura espacial en cine y televisión: los viajes de ciencia ficción en el macrocosmos en conmemoración de los noventa años del natalicio de Neil Armstrong Películas y episodios de series de televisión consultadas 2001: A Space Odyssey (Movie, 1968) 2010: The Year We Make Contact (Movie, 1984) A Trip to the Moon (Movie, 1902) Abbott and Costello Go to Mars (Movie, 1953) After Earth (Movie, 2013) Alien franchise: Alien (Movie, 1979) Aliens (Movie, 1986) Alien 3 (Movie, 1992) Alien: Resurrection (Movie, 1997) Prometheus (Movie, 2012) Alien: Covenant (Movie, 2017) Alien: Containment (Short Film, 2019) Alien: Specimen (Short Film, 2019) Alien: Night Shift (Short Film, 2019) Alien: Ore (Short Film, 2019) Alien: Harvest (Short Film, 2019) Alien: Alone (Short Film, 2019) Alien Abduction (Movie, 2005) Alien Armageddon (Movie, 2011) Alien Cargo (Movie, 1999) Alien Expedition (Movie, 2018) Alien Nation (Movie, 1988) Alien Siege (Movie, 2005) Alien Uprising (Movie, 2008) Angry Red Planet (Movie, 1959) Apollo 13 (Movie, 1995) Apollo 18 (Movie, 2011) Arena (Movie, 1989) Armageddon (Movie, 1998) Avatar (Movie, 2009) Babylon 5 franchise Babylon 5: The Gathering (Movie, 1993) Babylon 5 (TV Series, 110 episodes, 1994-1998) In the Beginning (Movie, 1998) Thirdspace (Movie, 1998) The River of Souls (Movie, 1998) A Call to Arms (Movie, 1999) Crusade (TV Series, 13 episodes, 1999) The Legend of the Rangers: To Live and Die in Starlight (Movie, 2002) Babylon 5: The Lost Tales: Voices in the Dark (Direct to Video, 2 episodes, 2006) Barbarella (Movie, 1968) -

Show Guide 2003

PLUS 2003 OFFICIAL ROYAL MELBOURNE Ui E SEPTEMBER 18-28 TAKE THE HARD WORK OUT OF YARD WORK... EASY STARTING 1-start' OPTIONS AMIABLE ON MOST „new moDas 0 AWARD WINNING SYSTEM ONINNif "NM BRUSHCUTIERS & TRIMMERS HEDGE TRIMMERS N1111.11.011w.4 POWER BLOWN FROM S379* SAVE SSS FROM $599* SAVE $SS FROM $399* SAVE $$$ For the name of your local Allpower Garden Machinery Centre ph: (03) 9990 3344 or visit us at www.allpower.com.au TRADE-IN'S NOT INCLUDED 26'0 2 le•A HS„wr Alipower for Suprrwiff, Echo, Arians, Sligo, Power Pruner, Moffett, Chipper Chopper and Mitsubishi PARTICIPATING DEALERS ONLY. FREiG1-17 4 PRE-DELIVERS NOT INCLUDED ••••°' FACT: The total spectator capacity of Cadbury Arena is about 22,000 2 OFFICIAL ROYAL MELBOURNE SHOW GUIDE Herald Sun dipowi 0°11 A WELCOME NOTE Follow the Yellow Brick Road OLLOW the Yellow Brick Road at the Show. It will lead you on a F fun and nutritious journey through the new attractions of this Jack Seymour year's event. The Yellow Brick Road continues its President tradition of being the best value-for- money showbag that is healthy for all Royal Agricultural the family. The journey starts when you pay $9 Society of Victoria at any of the main entrances or at the new The Weekly Times Victorian WELCOME to Six Worlds —One Agribusiness Showcase (opposite the Great Show. That is the Royal carpark entrance). Melbourne Show of 2003. Present the token from Page 4 of this The show is Victoria's largest and longest-running annual Show Guide to receive a $1 discount. -

![WHY DO PEOPLE IMAGINE ROBOTS] This Project Analyzes Why People Are Intrigued by the Thought of Robots, and Why They Choose to Create Them in Both Reality and Fiction](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7812/why-do-people-imagine-robots-this-project-analyzes-why-people-are-intrigued-by-the-thought-of-robots-and-why-they-choose-to-create-them-in-both-reality-and-fiction-6717812.webp)

WHY DO PEOPLE IMAGINE ROBOTS] This Project Analyzes Why People Are Intrigued by the Thought of Robots, and Why They Choose to Create Them in Both Reality and Fiction

Project Number: LES RBE3 2009 Worcester Polytechnic Institute Project Advisor: Lance E. Schachterle Project Co-Advisor: Michael J. Ciaraldi Ryan Cassidy Brannon Cote-Dumphy Jae Seok Lee Wade Mitchell-Evans An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science [WHY DO PEOPLE IMAGINE ROBOTS] This project analyzes why people are intrigued by the thought of robots, and why they choose to create them in both reality and fiction. Numerous movies, literature, news articles, online journals, surveys, and interviews have been used in determining the answer. Table of Contents Table of Figures ...................................................................................................................................... IV Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. I Literature Review .................................................................................................................................... 1 Definition of a Robot ........................................................................................................................... 1 Sources of Robots in Literature ............................................................................................................ 1 Online Lists ..................................................................................................................................... -

DDA Project Could Be Enhanced by FTE Funds

250 (^Serving The Lowell Area for over 100 Years ^ TOT The LoweU Ledger Volume 19, Issue 1 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, November 16,1994 C-l fp,.' ^ CI a^-s- be***- 1 \ \ \ \ \ 11 n AVV y** P U f* i v « '• mm r&ft#*: v.<Sr^r f J •r (tr nr ton f e t> Wv* JWHRTTV'- -rj» x This is a sketch of the proposed riverfront design for the city of Lowell. The city will begin work on its DDA project in 1995. DDA project could be enhanced by FTE funds By Thad Kraus Swanson also noted that Spring Lake has a $1.3 the funds. Lowell Ledger Editor the repaving of M-21 in the million bond issue. The con- Should Lowell be granted city is being scheduled for struction will start in the FTE funds, they would not be 1996. Bridge improvements spring. available until the construc- Through the Federal and needed curb replacement Spring Lake Village tion season (April) of 1996. Transportation Enhancement will be handled at the state Manager Eric DeLong said The application deadline is Fund, the Lowell Downtown expense. its match with the FTE pro- April 15, 1995. Development Authority has Through the Federal gram was 50-50 dollar match- If Lowell were to receive an opportunity to improve Transportation Enhancement ing. these additional funds, they upon its roughly $ 1.2 million (FTE) program, cities are "We included the monies could possibly be used toward downtown improvement asked to put in a minimum of from the Federal Transporta- additional landscaping and/ project. -

Collectable Toys, Models, Model Railways, Dolls and Teddy Bears, Automobilia and Railwayana

Collectable Toys, Models, Model Railways, Dolls and Teddy Bears, Automobilia and Railwayana. Saturday 23 March 2013 10:00 Aston's Toy Auctions Baylies Hall Tower Street Dudley DY1 1NB Aston's Toy Auctions (Collectable Toys, Models, Model Railways, Dolls and Teddy Bears, Automobilia and Railwayana.) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1 Mounted. Ex-shop stock. Appears VG with some minor paint Britains Herald Swoppets 641 Cowboy Firing Pistol - Mounted. loss, includes 'I'm A Swoppet!' tag, in VG box with label peeling Ex-shop stock. Appears VG/E with some minor paint loss, in off but present. VG box with original complaint slip. Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 Lot: 11 Lot: 2 Britains Herald Swoppets The War of The Roses 15th Century Britains Herald Swoppets H631 Cowboy Bank Robber - Mounted Knight - H1450 with Standard. Appears VG although Mounted. Ex-shop stock. Appears VG/E with some very minor very fine lines/crazing visible on the horse, still displays well. paint loss, includes 'I'm A Swoppet!' tag, in VG box. Inclues 'Swoppet' label and tent-style box with base flaps Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 unattached but present. [Collection Only] Estimate: £20.00 - £40.00 Lot: 3 Britains Herald Swoppets H634 Cowboy Firing Rifle - Mounted. Lot: 12 Ex-shop stock. Appears VG/E with 'I'm A Swoppet!' tag, in VG Trade pack of 6 x Britains Herald Swoppets 535 Indian Brave box with 'odd pieces' written in red pen on one end. with Tomahawk - Mounted. Ex-shop stock. Appear overall Estimate: £30.00 - £50.00 VG/E, two with discolouration to white loin cloth, one horse has light crazing/lines to body. -

The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader

University of Kentucky UKnowledge American Popular Culture American Studies 5-2-2008 The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader J. P. Telotte Georgia Institute of Technology Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Telotte, J. P., "The Essential Science Fiction Television Reader" (2008). American Popular Culture. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_american_popular_culture/8 THE ESSENTIAL SCIENCE FICTION TELEVISION READER ESSENTIAL READERS IN CONTEMPORARY MEDIA AND CULTURE This series is designed to collect and publish the best scholarly writing on various aspects of television, film, the Internet, and other media of today. Along with providing original insights and explorations of criti- cal themes, the series is intended to provide readers with the best avail- able resources for an in-depth understanding of the fundamental issues in contemporary media and cultural studies. Topics in the series may include, but are not limited to, critical-cultural examinations of cre- ators, content, institutions, and audiences associated with the media industry. Written in a clear and accessible style, books in the series include both single-author works and edited collections. -

Searching Answers

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. u.s. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs . 'National Institute oj Justice: i "National Institute of Justice ~ Searching or Answers Annual Evaluation Report Drugs and Crime 1993-1994 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------~ Letter of Transmittal To the President, the Attorney General, and the Congress: Pursuant to Section 520 of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 (Public Law 100-690), I have the honor to transmit herewith Searching for Answers, the National Institute of Justice's Evaluation Report on Drugs and Crime for fiscal years 1993-1994. espectfully :mbmitted, ~N eem~ Di ector N ional Institute of Justice Washington, DC May 1995 SEARCHING FOR ANSWERS NCJRS SEP 113 1995 ANNUAL EVALUATION REPORT ON DRUGS AND CRIME: 1993-1994 A Report to the President, the Attorney General, and the Congress 155487 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this _ : .. material has been grpr&gfic Lornain/OJP /NIJ u. S. Department of Justice to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the 4I/iIiIII88 owner. National Institute of Justice Jeremy Travis Director Report Editors Mary G. Graham Winifred Reed The grants described in this report are monitored by staff members of the National Institute of Justice, who provided invaluable assistance in the development of this report. -

Two Arrested in Crackdown

Britain's hottest hardman bites the bullet this week in Incorporating juice magazine Guardian/ NUS Student Newspaper of the Year May 23,1997 Vol 27: Issue 23 DRUGS SQUAD BUSTS HALLS Two arrested Police hunt firebomb riot thugs A DRUGS gang is being blamed for last week's riois when Hyde Park was turned in crackdown into a battleground of bla/ing By JAN HENEK cars, u n'/rv l.diini /)<;u'.s. Police say the riots were a retaliation by drug dealers for POLICE arrested two freshers the raid on The Little Park as part of a covert operation to pub. similar to an incident two years ago, when the Jolly crack down on drugs in Brewer pub on Hyde Park Road was ra/ed to the ground university halls. after drug dealers were Special officers swooped in a dawn prevented from conducting business there. raid on Bodington hall, charging two The Hyde Park community agreed the riots have nothing students and cautioning two more for to do with lack of jobs or drugs offences. money, but are a result of the Police officers posed as drug dealers in an local drugs problem, which has been escalating during undercover offensive said to include the recent years in many of Leeds tapping of phones in halls of residence. inner-city communities. "They are going way too far," said one Bodington They say the drugs hall resident. "The police came here and pretended to situation is having a direct he drug dealers. It looked like entrapment." affect on the community. The two freshers face charges of intent to supply drugs Teenage girls are turning to and possession of cannahis.