Shivaji's Fortunes and Possessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recently Noticed Inscription from Lohagadwadi Ancient Asia (Fort Lohagad), District Pune, Maharashtra, India

Pradhan, S, et al. 2020. Recently Noticed Inscription from Lohagadwadi Ancient Asia (Fort Lohagad), District Pune, Maharashtra, India. Ancient Asia, 11: 1, pp. 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/aa.187 RESEARCH PAPER Recently Noticed Inscription from Lohagadwadi (Fort Lohagad), District Pune, Maharashtra, India Shrikant Pradhan*, Abhinav Kurkute† and Vivek Kale‡ In 1969 an early Jaina inscription was discovered from Pale cave, Taluka Mawal, District Pune, Maharashtra, by H.D. Sankalia and Shobhana Gokhale, Pune (1971: 67–69). It was an important discovery of an early Jaina inscription in western India. While studying the Pale inscription, both the authors had cited that “There must be many more such inscriptions, which need to be discovered.” Recently an inscription is noticed in one of the small rock-cut excavations group in fort Lohogad, Lohagadwadi by a group of trekking and exploration enthusiasts. While observing this inscription, it proposes some early characteristics of Brāhmī script. It is significant to mention that the Lohagadwadi inscription starts with ‘Namo arahaṁtānaṁ’ and the donor’s name Idarakhita. Interestingly, the inscription shows close affinity to the Pale cave inscription and proposes to be an important early inscription of Jainism in Maharashtra by the same donor mentioned in the Pale inscription. Probably, a small cave complex of Lohagadwadi, as primarily described in this article, dates back to the early rock-cut activity of Jainism in Maharashtra. Introduction eastern precipice, though both are located a little distance The well-known medieval fort of Lohagad is located from the above-mentioned excavations. Earlier, Burgess approximately 25 km south of Pale Cave. -

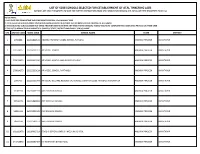

List of 6038 Schools Selected for Establishment of Atal Tinkering

LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. LAST DATE FOR COMPLETING THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS : 31st JANUARY 2020 2. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST OPEN A NEW BANK ACCOUNT IN A PUBLIC SECTOR BANK FOR THE PURPOSE OF ATL GRANT. 3. THESE SELECTED SCHOOLS MUST NOT SHARE THEIR INFORMATION WITH ANY THIRD PARTY/ VENDOR/ AGENT/ AND MUST COMPLETE THE COMPLIANCE PROCESS ON THEIR OWN. 4. THIS LIST IS ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF STATE, DISTRICT AND FINALLY SCHOOL NAME. S.N. ATL UID CODE UDISE CODE SCHOOL NAME STATE DISTRICT 1 2760806 28222800515 ANDHRA PRADESH MODEL SCHOOL PUTLURU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 2 132314217 28224201013 AP MODEL SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 3 574614473 28223600320 AP MODEL SCHOOL AND JUNIOR COLLEGE ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 4 278814373 28223200124 AP MODEL SCHOOL RAPTHADU ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 5 2995459 28222500704 AP SOCIAL WELFARE RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL JUNIOR COLLEGE FOR GIRLS KURUGUNTA ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 6 13701194 28220601919 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 7 15712075 28221890982 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 8 56051196 28222301035 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 9 385c1160 28221591153 AVR EM HIGH SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 10 102112978 28220902023 GOOD SHEPHERD ENGLISH MEDIUM SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR 11 243715046 28220590484 K C NARAYANA E M SCHOOL ANDHRA PRADESH ANANTAPUR LIST OF 6038 SCHOOLS SELECTED FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ATAL TINKERING LABS (SCHOOLS ARE KINDLY REQUESTED TO WAIT FOR FURTHER INSTRUCTIONS FROM ATAL INNOVATION MISSION, NITI AAYOG ON THEIR REGISTERED EMAIL IDs) PLEASE NOTE:- 1. -

Siva Chhatrapati, Being a Translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with Extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijaya, with Notes

SIVA CHHATRAPATI Extracts and Documents relating to Maratha History Vol. I SIVA CHHATRAPATI BEING A TRANSLATION OP SABHASAD BAKHAR WITH EXTRACTS FROM CHITNIS AND SIVADIGVTJAYA, WITH NOTES. BY SURENDRANATH SEN, M.A., Premchaxd Roychand Student, Lectcrer in MarItha History, Calcutta University, Ordinary Fellow, Indian Women's University, Poona. Formerly Professor of History and English Literature, Robertson College, Jubbulpore. Published by thz UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 1920 PRINTED BY ATCLCHANDKA BHATTACHABYYA, AT THE CALCUTTA UNIVEB8ITY PEE 88, SENATE HOUSE, CALCUTTA " WW**, #rf?fW rT, SIWiMfT, ^R^fa srre ^rtfsre wwf* Ti^vtm PREFACE The present volume is the first of a series intended for those students of Maratha history who do not know Marathi. Original materials, both published and unpublished, have been accumulating for the last sixtv years and their volume often frightens the average student. Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, therefore, suggested that a selection in a handy form should be made where all the useful documents should be in- cluded. I must confess that no historical document has found a place in the present volume, but I felt that the chronicles or bakhars could not be excluded from the present series and I began with Sabhasad bakhar leaving the documents for a subsequent volume. This is by no means the first English rendering of Sabhasad. Jagannath Lakshman Mankar translated Sabhasad more than thirty years ago from a single manuscript. The late Dr. Vincent A. Smith over- estimated the value of Mankar's work mainly because he did not know its exact nature. A glance at the catalogue of Marathi manuscripts in the British Museum might have convinced him that the original Marathi Chronicle from which Mankar translated has not been lost. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Satara. in 1960, the North Satara Reverted to Its Original Name Satara, and South Satara Was Designated As Sangli District

MAHARASHTRA STATE GAZETTEERS Government of Maharashtra SATARA DISTRICT (REVISED EDITION) BOMBAY DIRECTORATE OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONARY AND PUBLICATION, MAHARASHTRA STATE 1963 Contents PROLOGUE I am very glad to bring out the e-Book Edition (CD version) of the Satara District Gazetteer published by the Gazetteers Department. This CD version is a part of a scheme of preparing compact discs of earlier published District Gazetteers. Satara District Gazetteer was published in 1963. It contains authentic and useful information on several aspects of the district and is considered to be of great value to administrators, scholars and general readers. The copies of this edition are now out of stock. Considering its utility, therefore, need was felt to preserve this treasure of knowledge. In this age of modernization, information and technology have become key words. To keep pace with the changing need of hour, I have decided to bring out CD version of this edition with little statistical supplementary and some photographs. It is also made available on the website of the state government www.maharashtra.gov.in. I am sure, scholars and studious persons across the world will find this CD immensely beneficial. I am thankful to the Honourable Minister, Shri. Ashokrao Chavan (Industries and Mines, Cultural Affairs and Protocol), and the Minister of State, Shri. Rana Jagjitsinh Patil (Agriculture, Industries and Cultural Affairs), Shri. Bhushan Gagrani (Secretary, Cultural Affairs), Government of Maharashtra for being constant source of inspiration. Place: Mumbai DR. ARUNCHANDRA S. PATHAK Date :25th December, 2006 Executive Editor and Secretary Contents PREFACE THE GAZETTEER of the Bombay Presidency was originally compiled between 1874 and 1884, though the actual publication of the volumes was spread over a period of 27 years. -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE - 4 Page : 1 schoolwise performance of Fresh Regular candidates MARCH-2020 Division : MUMBAI Candidates passed School No. Name of the School Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 16.01.001 SAKHARAM SHETH VIDYALAYA, KALYAN,THANE 185 185 22 57 52 29 160 86.48 27210508002 16.01.002 VIDYANIKETAN,PAL PYUJO MANPADA, DOMBIVLI-E, THANE 226 226 198 28 0 0 226 100.00 27210507603 16.01.003 ST.TERESA CONVENT 175 175 132 41 2 0 175 100.00 27210507403 H.SCHOOL,KOLEGAON,DOMBIVLI,THANE 16.01.004 VIVIDLAXI VIDYA, GOLAVALI, 46 46 2 7 13 11 33 71.73 27210508504 DOMBIVLI-E,KALYAN,THANE 16.01.005 SHANKESHWAR MADHYAMIK VID.DOMBIVALI,KALYAN, THANE 33 33 11 11 11 0 33 100.00 27210507115 16.01.006 RAYATE VIBHAG HIGH SCHOOL, RAYATE, KALYAN, THANE 151 151 37 60 36 10 143 94.70 27210501802 16.01.007 SHRI SAI KRUPA LATE.M.S.PISAL VID.JAMBHUL,KULGAON 30 30 12 9 2 6 29 96.66 27210504702 16.01.008 MARALESHWAR VIDYALAYA, MHARAL, KALYAN, DIST.THANE 152 152 56 48 39 4 147 96.71 27210506307 16.01.009 JAGRUTI VIDYALAYA, DAHAGOAN VAVHOLI,KALYAN,THANE 68 68 20 26 20 1 67 98.52 27210500502 16.01.010 MADHYAMIK VIDYALAYA, KUNDE MAMNOLI, KALYAN, THANE 53 53 14 29 9 1 53 100.00 27210505802 16.01.011 SMT.G.L.BELKADE MADHYA.VIDYALAYA,KHADAVALI,THANE 37 36 2 9 13 5 29 80.55 27210503705 16.01.012 GANGA GORJESHWER VIDYA MANDIR, FALEGAON, KALYAN 45 45 12 14 16 3 45 100.00 27210503403 16.01.013 KAKADPADA VIBHAG VIDYALAYA, VEHALE, KALYAN, THANE 50 50 17 13 -

District Census Handbook, North Satara

Government of Bombay NORTH SA TARA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK (Based on the 1951 Census) 315.4792 BOMB!,y 1951 NOWPADA" THAnA.. h1icRtiOI~:8 8~tles Deuot, fnstitute of Science Buulaiu,= NOR DCH ' I • 1mbs:y City l. from the {'~veM.lfuent Book"Depot,9'h.acui • from eh" mOflll!8i1l or tbr<>l1~n the High CommV"'ioo.". '"liiQf8 h_u~. ",HawyCtl. London. W.O. 2, or through any recognized Bonk.;lIor. Price-Rs. 2 As. B 01" 4 ,~. 6 d. 1952 .. '16 C Z Q ~ III Ii .... !'i"" 0 's ct N' t..) ~ ~ '1) 0::- ~ III• o ... .... § . I -1111 (/) 0 - t" _"'Q Q ~ Ie:(·i J-~ cx~ 0 Z ~ ~ < ~ ~ ~ ~ h .~~ ~ ~ ~. It () ~ ~ CONTENTS. A. General Population Tables. A-I Area, Houses and Population ~-.'i A-III Towns and Villages classified by Population 6-9 A-V Towns arranged territorially with population by livelihood classes. IO-Il B. Economic Tables. .. B-1 Livelihood Classes and Sub-Classes 12-19 B-If Secondary Means of Livelihood 20-:35 B-III Employers, Employees and Independent Workers in / . Industries and Services by Divisions and Sub-Divisions. 26-G9 Index of non-agricultural occupations in the district. .~. 10-77 C. Household and Age (Sample) Tables. C-I Household (Size and Composition) 78-81 C-II Livelihood classes by Age Groups ...• 82-85 C-III Age and Civil condition 86-95 C-IV Age and Literacy 96-103 C-V Single Year Age Returns 104-107 D. Social and Cultural Tables. D-! Languages: (i) Mother Tongue ... ... 108-112 (ii) Bilingualism .•.. 113-115 D-II Religion 116~1l7 . -

Flora of Aphyllophorales from Pune District- Part I

Journal on New Biological Reports 2(3): 188-227 (2013) ISSN 2319 – 1104 (Online) Flora of Aphyllophorales from Pune District- Part I Ranadive KR 1* , Jite PK 2, Ranade VD 3 and Vaidya JG 2 1Waghire College Saswad, Department of Botany, Pune – 412301, Maharashtra, India. 2Department of Botany, Mycology laboratory University of Pune, Pune – 411007, Maharashtra, India 3Abasaheb Garware College, Department of Botany, Karve Road, Pune, Maharashtra, India (Received on: 25 July, 2013; accepted on: 29 August, 2013) ABSTRACT The tropical forests of Pune District are mainly classified into Tropical stunted semi-evergreen forests, stunted semi- evergreen scrub forests, moist deciduous and dry deciduous forests. In the present study a total of 20 species of Aphyllophorales (8 families and 14 genera) from the 10 respective hosts were identified out of 126 collected specimens from 15 different localities throughout the Western Ghats of Pune districts, Maharashtra State . Key Words: Fungi, Maharashtra State, Pune, Western Ghats. INTRODUCTION Aphyllophorales order was proposed by In his “Essai Taxonomique ”, Patouillard made Rea, after Patouillard, for Basidiomycetes having groupings in polypores on the basis of such macroscopic basidiocarps in which the hymenophore characters as detailed hyphal morphology, structure is flattened (Thelephoraceae), club-like of the pileus and characters of basidia, spores and (Clavariaceae), tooth-like (Hydnaceae) or has the cystidia. He divided the Basidiomycetes into hymenium lining tubes (Polyporaceae) or some times Homobasidiomycetes with secondary spores and the on lamellae, the poroid or lamellate hymenophores Heterobasidiomycetes without secondary spores. The being tough and not fleshy as in the Agaricales. Heterobasidiomycetes were further subdivided Traditionally the order has had a core of four families according to the septation of the basidia. -

Shivaji the Great

SHIVAJI THE GREAT BY BAL KRISHNA, M. A., PH. D., Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society. the Royal Economic Society. London, etc. Professor of Economics and Principal, Rajaram College, Kolhapur, India Part IV Shivaji, The Man and His .Work THE ARYA BOOK DEPOT, Kolhapur COPYRIGHT 1940 the Author Published by The Anther A Note on the Author Dr. Balkrisbna came of a Ksbatriya family of Multan, in the Punjab* Born in 1882, be spent bis boyhood in struggles against mediocrity. For after completing bis primary education he was first apprenticed to a jewel-threader and then to a tailor. It appeared as if he would settle down as a tailor when by a fortunate turn of events he found himself in a Middle Vernacular School. He gave the first sign of talents by standing first in the Vernacular Final ^Examination. Then he joined the Multan High School and passed en to the D. A. V. College, Lahore, from where he took his B. A* degree. Then be joined the Government College, Lahore, and passed bis M. A. with high distinction. During the last part of bis College career, be came under the influence of some great Indian political leaders, especially of Lala Lajpatrai, Sardar Ajitsingh and the Honourable Gopal Krishna Gokhale, and in 1908-9 took an active part in politics. But soon after he was drawn more powerfully to the Arya Samaj. His high place in the M. A. examination would have helped him to a promising career under the Government, but he chose differently. He joined Lala Munshiram ( later Swami Shraddha- Btnd ) *s a worker in the Guruk.ul, Kangri. -

5. the Foundation of the Swaraj

5. The Foundation of the Swaraj In the first half of the seventeenth century, an epoch making personality emerged in Maharashtra - Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj. He established Swaraj by challenging the unjust ruling powers here. Shivaji Maharaj was born at the Shivneri fort near Junnar in Pune district on the day of Phalgun Vadya Tritiya in the Shaka year 1551, that is on 19 February 1630. Shahajiraje : Shahajiraje, the father of Shivaji Maharaj was a pre-eminent Sardar in the Deccan. The Mughals had launched a campaign to conquer the Nizamshahi Kingdom. The Adilshah of Bijapur allied with the Mughals in this campaign. Shahaji Maharaj did not wish the Mughals to get an entry into the South. So he tried to save Nizamshahi by offering stiff resistance to the Mughals. But he could not withstand the combined might of the Mughals Shahajiraje and the Adilshah. The Nizamshahi was defeated and came to an end in 1636 CE. After the Nizamshahi was wiped out, Shahajiraje became a Sardar of the Adilshah of Bijapur. The region comprising Pune, Supe, Indapur and Chakan parganas located between the Bheema and Neera rivers was vested in Shahajiraje as a jagir. This was continued by the Adilshah, and he also granted the jagir of Bengaluru and the neighbouring areas in Karnataka to Shahajiraje. For your information Jahagir or jagir means the right to enjoy the revenue of a region. The Sardars in the service of rulers used to get the revenue of the region as income instead of getting salaries directly. The region was chosen in such a way that the revenue would be equal to the salary. -

Tourist Attractions in Mahabaleshwar Hill Station, Satara District(Maharashtra)

Golden Research Thoughts Volume 2, Issue. 3, Sept 2012 Available online at www.aygrt.net ISSN:-2231-5063 ORIGINAL ARTICLE GRT Tourist Attractions In Mahabaleshwar Hill Station, Satara District(Maharashtra) Gatade D. G.1 and Abhay Patil2 1Professor and Head,Department of Geography , A.S.C.College, Ramanandnagar, (Burli), Dist- [email protected] 2Associate Professor and Head, Department of History , A.S.C.College,Ramanandnagar, (Burli), Dist- Sangli Abstract: In the present research paper an attempt has been made to highlight tourist attractions in Mahabaleshwar hill station of Satara district of Maharashtra. The entire study is based on primary & secondary data as well as empirical knowledge. Primary data is collected through the field survey and observation methods.Secondary data is taken from government reports, Gazetteer of Satara district, District Census Handbook of Satara and few websites. Tourist point is taken as study investigation unit. Study reveals that Mahabaleshwar has several attractions of which 20 attractions have most significant from the view point of the tourists of India and abroad. INTRODUCTION Mahabaleshwar is one of the important tourist destinations of Maharashtra from the view point of tourists of India and abroad. This destination has more 50 attractions among them 20 attractions are very popular..Nearly 4.5 million tourist per year visit to this destination. Hence the present study is taken from the view point tourism. No update in formations are available about these points In the present research paper an attempt has been made to highlight geographical and historical perspective of twenty attractions of the Mahabaleshwar hill station. -

Shivaji the Founder of Maratha Swaraj

26 B. I. S. M. Puraskrita Grantha Mali, No. SHIVAJI THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ BY C. V. VAIDYA, M. A., LL. B. Fellow, University of Bombay, Vice-Ctianct-llor, Tilak University; t Bharat-Itihasa-Shamshndhak Mandal, Poona* POON)k 1931 PRICE B8. 3 : B. Printed by S. R. Sardesai, B. A. LL. f at the Navin ' * Samarth Vidyalaya's Samarth Bharat Press, Sadoshiv Peth, Poona 2. BY THE SAME AUTHOR : Price Rs* as. Mahabharat : A Criticism 2 8 Riddle of the Ramayana ( In Press ) 2 Epic India ,, 30 BOMBAY BOOK DEPOT, BOMBAY History of Mediaeval Hindu India Vol. I. Harsha and Later Kings 6 8 Vol. II. Early History of Rajputs 6 8 Vol. 111. Downfall of Hindu India 7 8 D. B. TARAPOREWALLA & SONS History of Sanskrit Literature Vedic Period ... ... 10 ARYABHUSHAN PRESS, POONA, AND BOOK-SELLERS IN BOMBAY Published by : C. V. Vaidya, at 314. Sadashiv Peth. POONA CITY. INSCRIBED WITH PERMISSION TO SHRI. BHAWANRAO SHINIVASRAO ALIAS BALASAHEB PANT PRATINIDHI,B.A., Chief of Aundh In respectful appreciation of his deep study of Maratha history and his ardent admiration of Shivaji Maharaj, THE FOUNDER OF MARATHA SWARAJ PREFACE The records in Maharashtra and other places bearing on Shivaji's life are still being searched out and collected in the Shiva-Charitra-Karyalaya founded by the Bharata- Itihasa-Samshodhak Mandal of Poona and important papers bearing on Shivaji's doings are being discovered from day to day. It is, therefore, not yet time, according to many, to write an authentic lifetof this great hero of Maha- rashtra and 1 hesitated for some time to undertake this work suggested to me by Shrimant Balasaheb Pant Prati- nidhi, Chief of Aundh.