A Rare Cause of Unexplained Abdominal Pain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants

Therapeutic Class Overview Anticonvulsants INTRODUCTION Epilepsy is a disease of the brain defined by any of the following (Fisher et al 2014): ○ At least 2 unprovoked (or reflex) seizures occurring > 24 hours apart; ○ 1 unprovoked (or reflex) seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after 2 unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years; ○ Diagnosis of an epilepsy syndrome. Types of seizures include generalized seizures, focal (partial) seizures, and status epilepticus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018, Epilepsy Foundation 2016). ○ Generalized seizures affect both sides of the brain and include: . Tonic-clonic (grand mal): begin with stiffening of the limbs, followed by jerking of the limbs and face . Myoclonic: characterized by rapid, brief contractions of body muscles, usually on both sides of the body at the same time . Atonic: characterized by abrupt loss of muscle tone; they are also called drop attacks or akinetic seizures and can result in injury due to falls . Absence (petit mal): characterized by brief lapses of awareness, sometimes with staring, that begin and end abruptly; they are more common in children than adults and may be accompanied by brief myoclonic jerking of the eyelids or facial muscles, a loss of muscle tone, or automatisms. ○ Focal seizures are located in just 1 area of the brain and include: . Simple: affect a small part of the brain; can affect movement, sensations, and emotion, without a loss of consciousness . Complex: affect a larger area of the brain than simple focal seizures and the patient loses awareness; episodes typically begin with a blank stare, followed by chewing movements, picking at or fumbling with clothing, mumbling, and performing repeated unorganized movements or wandering; they may also be called “temporal lobe epilepsy” or “psychomotor epilepsy” . -

Abdominal Epilepsy in an Adult: a Diagnosis Often Missed Psychiatry Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/19873.8600 Case Report Abdominal Epilepsy in an Adult: A Diagnosis Often Missed Psychiatry Section DEVAVRAT G HARSHE1, SNEHA D HARSHE2, GURUDAS R HARSHE3, GAYATRI G HARSHE4 ABSTRACT Abdominal Epilepsy (AE) is a variant of temporal lobe epilepsy and is commonly seen in pediatric age group. There are however, multiple reports of abdominal epilepsy in adolescents and even in adults. Chronic and recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms with one or more neuropsychiatric manifestations are often the presenting picture for a patient with AE. Such patients therefore, are more likely to consult a general practioner, a physician, a surgeon or a gastroenterologist than consulting a psychiatrist or a neurologist. We hereby present such a case of AE in an adult with review of similar reports. Keywords: Abdominal pain, Consultation liaison psychiatry, Temporal lobe CASE REPORT persisted. Considering the episodic hypertension with headache, A 45-year-old female with no past significant medical or psychiatric pheochromocytoma was suspected and was ruled out, when 24 history was referred to a psychiatric nursing home by a surgeon hours urinary Vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and serum metanephrines for suspected psychogenic abdominal pain. History consisted of turned out to be normal. Abdominal migraine and porphyria were multiple clustered episodes of abdominal pain since one year; each ruled out considering the duration of episodes, lack of any family episode consisting of insufferable abdominal pain with genuine history and absence of other findings supportive of porphyria. distress. Pain would begin at the right iliac fossa and radiate to Abdominal epilepsy was then considered as the diagnosis and was the umbilical area. -

Epilepsy and Communication

fasic England Gloss ry Epilepsy and communication Epilepsy is a chronic disorder of the brain • Temporal Lobe epilepsy characterised by recurrent seizures, which affects • Dravet syndrome people worldwide (WHO, 2016). The World Health Organisation deKnes a seizure as a transient loss of There are a range of communication difficulties function of all or part of the brain due to excessive associated with epilepsy. For some people, electrical discharges in a group of brain cells. Physical, communication difficulties can become more sensory or other functions can be temporarily lost. pronounced at times immediately before, during or after seizure activity. Epilepsy affects 1 in 177 young people under the age of 25 so there are around 112,000 young people with Communication difficulties may include: epilepsy in the UK (Joint Epilepsy Council, 2011). In 75% • Comprehension difficulties: Children may Knd it of people, seizures are well controlled with medication hard to understand what others are saying to but 25% continue to have seizures despite treatment. them or what is expected of them, and may struggle to understand environmental cues, daily Epilepsy can be linked with learning, behavioural and routines or activity sequences. speech and language difficulties. This is increasingly • Attention and listening difficulties: Children recognised and the risks are greater if epilepsy occurs may have difficulties in attending to spoken before 2 years of age. Parkinson (1994) found that language, or to an activity. from a small study of children referred for assessment of their epilepsy, 40% had undiagnosed language • Expressive difficulties: It may be hard for impairment of varying degrees of severity. -

14582 IBE Newsletter 2003

International Bureau for Epilepsy Annual Report 2003 Setting the Standard From Our Vision IBE has a vision of the world where everywhere ignorance and fear about epilepsy are replaced by understanding and care. Our Mission IBE exists to improve the social condition and quality of life of people with epilepsy and those who care for them. Our Goals • ORGANISATION To provide an international umbrella organisation for national epilepsy organisations whose primary purpose is to improve the social condition and quality of life of people with epilepsy and those who care for them. • SUPPORT To provide a strong global network to support the development of new Chapters, to support existing Chapters to develop to their fullest potential and to encourage co-operation and contact between Chapters. • COMMUNICATION To promote the facts about epilepsy and to communicate IBE’s vision, mission and messages to the widest possible audience. • EDUCATION To increase understanding and knowledge of epilepsy. • REPRESENTATION To provide an international and global platform for the representation of epilepsy. 2 International Bureau for Epilepsy Foreward During my fifteen years working, first in the British Parliament and Government and now in the European Parliament, I have seen and welcomed an ever-increasing awareness of the importance and benefits of strong partnerships. Networks and alliances are more than just “buzz words” – they are proven methods of achieving desired goals. They may not be easy to achieve, but, once in place, they make it simpler for patients, carers, professionals and academics to explain health needs and options for action and they make it easier for policy-makers to listen and to understand what is needed. -

Best Practice Guidelines for Training

Best practice guidelines for training professional carers in the administration of Buccal (Oromucosal) Midazolam for the treatment of prolonged and / or clusters of epileptic seizures in the community Safe & Effective | Kind & Caring | Exceeding Expectation Epilepsy Nurses Association (ESNA) June 2019 1. Foreword One of the most important components of epilepsy care is the pre-hospital community management of prolonged or repeated seizures, which, if untreated, can increase the risk of status epilepticus. Convulsive status epilepticus is a medical emergency requiring admission to hospital and has a mortality rate of up to 20 per cent. Effective management of seizures in the community in people at high risk of status epilepticus could significantly reduce mortality, morbidity and emergency health care utilisation. The Joint Epilepsy Council issued guidance until it was disbanded in 2015, leaving a vacuum in the review and update of clinical guidelines. Unfortunately, the clinical processes ensuring the safety and consistency of buccal midazolam usage demonstrates considerable heterogeneity. There are no current guidelines, standards or pathways to ensure the safety of all involved in the process i.e. patient, carer or professional. ESNA is an organisation principally formed by nurses with an interest in epilepsy. Most ESNA members support or complete training for buccal midazolam to ensure core competencies are up to date and patient safety is protected. ESNA is joined by the International League Against Epilepsy (British Chapter) and the Royal College of Psychiatrists (ID Faculty) as the other principal specialist clinical stakeholders with an interest to ensure governance in this complex care area is addressed robustly. ESNA has collaborated with the ILAE and the Royal College of Psychiatrists to produce updated buccal midazolam guidance. -

Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review Ismail A

Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS) Volume 2 | Issue 2 Article 4 7-2007 Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review Ismail A. Khatri Shifa International Hospital Umar S. Chaudhry Shifa International Hospital Abdul Majeed Khatri Neurology Center, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA Zahid F. Cheema University of Oklahoma Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns Part of the Neurology Commons Recommended Citation Khatri, Ismail A.; Chaudhry, Umar S.; Khatri, Abdul Majeed; and Cheema, Zahid F. (2007) "Ictus Emeticus: Case Reports and Literature Review," Pakistan Journal of Neurological Sciences (PJNS): Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://ecommons.aku.edu/pjns/vol2/iss2/4 C A S E R E P O R T ICTUS EMETICUS: CASE REPORTS AND LITERATURE REVIEW Ismail A. Khatri1, Umar S. Chaudhry1, Abdul Majeed Khatri2, Zahid F. Cheema3 1Department of Neurology, Shifa International Hospital, Islamabad, Pakistan; 2 Neurology Center, Nacogdoches, Texas, USA; 3Department of Neurology, University of Oklahoma Medical Center, Oklahoma City, OK, USA Correspondence to: Dr. Khatri, Section of Neurology, Shifa International Hospitals Ltd., Pitras Bukhari Road, Sector H-8/4, Islamabad 46000, Pakistan. Tel: (92-51) 444-6801-30 Ext: 3175, 3025. Fax: (92-51) 486-3182. Email: [email protected] Pak J Neurol Sci 2007; 2(2):96-98 ABSTRACT The diagnosis of abdominal epilepsy came into vogue in the 1950s and 1960s. Vomiting as a manifestation of seizure has been given different names including ictus emeticus. We report three cases of this interesting albeit uncommon condition. It is important for physicians to familiarize themselves with this symptomatology so as not to overlook this unique presentation of epileptic seizures. -

Fenfluramine Hydrochloride for the Treatment of Seizures in Dravet Syndrome: a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Articles Fenfluramine hydrochloride for the treatment of seizures in Dravet syndrome: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial Lieven Lagae*, Joseph Sullivan*, Kelly Knupp, Linda Laux, Tilman Polster, Marina Nikanorova, Orrin Devinsky, J Helen Cross, Renzo Guerrini, Dinesh Talwar, Ian Miller, Gail Farfel, Bradley S Galer, Arnold Gammaitoni, Arun Mistry, Glenn Morrison, Michael Lock, Anupam Agarwal, Wyman W Lai, Berten Ceulemans, for the FAiRE DS Study Group Summary Background Dravet syndrome is a rare, treatment-resistant developmental epileptic encephalopathy characterised by Published Online multiple types of frequent, disabling seizures. Fenfluramine has been reported to have antiseizure activity in December 17, 2019 observational studies of photosensitive epilepsy and Dravet syndrome. The aim of the present study was to assess the https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(19)32500-0 efficacy and safety of fenfluramine in patients with Dravet syndrome. See Online/Comment https://doi.org/10.1016/ Methods In this randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, we enrolled children and young adults S0140-6736(19)31239-5 with Dravet syndrome. After a 6-week observation period to establish baseline monthly convulsive seizure *Contributed equally frequency (MCSF; convulsive seizures were defined as hemiclonic, tonic, clonic, tonic-atonic, generalised tonic- Department of Paediatric clonic, and focal with clearly observable motor signs), patients were randomly assigned through an interactive web Neurology, University of response system in a 1:1:1 ratio to placebo, fenfluramine 0·2 mg/kg per day, or fenfluramine 0·7 mg/kg per day, Leuven, Leuven, Belgium (Prof L Lagae MD); University of added to existing antiepileptic agents for 14 weeks. -

Dictionary of Epilepsy

DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS .· DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY PART I: DEFINITIONS PROFESSOR H. GASTAUT President, University of Aix-Marseilles, France in collaboration with an international group of experts ~ WORLD HEALTH- ORGANIZATION GENEVA 1973 ©World Health Organization 1973 Publications of the World Health Organization enjoy copyright protection in accord ance with the provisions of Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. For rights of reproduction or translation of WHO publications, in part or in toto, application should be made to the Office of Publications and Translation, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. The World Health Organization welcomes such applications. PRINTED IN SWITZERLAND WHO WORKING GROUP ON THE DICTIONARY OF EPILEPSY1 Professor R. J. Broughton, Montreal Neurological Institute, Canada Professor H. Collomb, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, University of Dakar, Senegal Professor H. Gastaut, Dean, Joint Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Aix-Marseilles, France Professor G. Glaser, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Conn., USA Professor M. Gozzano, Director, Neuropsychiatric Clinic, Rome, Italy Dr A. M. Lorentz de Haas, Epilepsy Centre "Meer en Bosch", Heemstede, Netherlands Professor P. Juhasz, Rector, University of Medical Science, Debrecen, Hungary Professor A. Jus, Chairman, Psychiatric Department, Academy of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland Professor A. Kreindler, Institute of Neurology, Academy of the People's Republic of Romania, Bucharest, Romania Dr J. Kugler, Department of Psychiatry, University of Munich, Federal Republic of Germany Dr H. Landolt, Medical Director, Swiss Institute for Epileptics, Zurich, Switzerland Dr B. A. Lebedev, Chief, Mental Health, WHO, Geneva, Switzerland Dr R. L. Masland, Department of Neurology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, USA Professor F. -

September 2019 Research Quarterly

THINK BIG RESEARCH Q UARTER LY ISSUE 11: SEPTEMBER 2019 MY SEIZURE GAUGE EPILEPSY LEARNING HEALTHCARE SYSTEM SUDEP INSTITUTE INNOVATOR SPOTLIGHT FOUNDATION AWARDEES IN THE NEWS WELCOME Every year, the Epilepsy Foundation hosts a leadership conference that brings together local Epilepsy Foundations to share best practices from the network. This year’s theme is “THINK BIG.” I love this theme as it perfectly captures our strategic planning approach. We think big, so that we can act big, to make meaningful change today that will bring hope for tomorrow. TO CELEBRATE THE THINK BIG THEME, we will be In 1997, Apple launched their Think Different campaign, devoting this fall issue to the ways that we are thinking which brought new life into a company that would go on big – from driving therapeutic innovations, to changing to help reshape how we interact with technology. The outcomes, and saving lives. On page 4, you can learn full text of the ad is below: about the exciting progress of the My Seizure Gauge team, an international consortium working together to create a seizure forecasting device that could assess “Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The the chance of seizures like a weather forecast. On page troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The 6, you can learn about our leadership of the Epilepsy ones who see things differently. They’re not fond of rules Learning Healthcare System, a new model to transform and they have no respect for the status quo. You can the healthcare system. On page 7, you can learn more quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. -

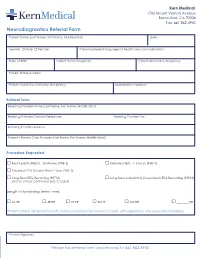

Neurodiagnostics Referral Form

Kern Medical 1700 Mount Vernon Avenue Bakersfield, CA 93306 Fax: 661.862.4940 Neurodiagnostics Referral Form Patient Name (Last Name, First Name, Middle Initial) Date Gender □ Male □ Female Patient preferred language for healthcare communication Date of Birth Patient Home Telephone Patient Alternative Telephone Patient Home Address Patient insurance company and plan(s) Authorization Number: Referral Form: Referring Provider Name (Last Name, First Name, Middle Initial) Referring Provider Contact Telephone Referring Provider Fax Referring Provider Address Patient’s Primary Care Provider (Last Name, First Name, Middle Initial) Procedure Requested: □ Routine EEG (REEG) - 20 Minutes (95816) □ Extended EEG - 1-2 Hours (95813) □ Extended EEG Greater than 2 Hours (95713) □ Long-Term EEG Recording (95716) □ Long-Term Ambulatory (Outpatient) EEG Recording (95953) EMU or Critical Continuous EEG (CCEEG) Length of Monitoring (select one): □ 24 HR □ 48 HR □ 72 HR □ 96 HR □ 120 HR □ ________ HR *Please attach last progress note, history and physical, insurance cards, demographics, any associated imaging. Provider Signature Please fax referral form and records to 661.862.4940 NEURODIAGNOSTICS Kern Medical offers the following EEG and EMU services Indications for routine Indications of Ambulatory Indications of VEEG study in How to Refer Patients to EEG VEEG EMU the EMU • After new onset seizure Ambulatory • Determine whether spells • Referrals can be arranged electroencephalography are epileptic seizures (spell by calling the Kern Medical • For diagnosing -

Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit

Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit A Resource for Parents with a Newly Diagnosed Child 136EMC Epilepsy & My Child Toolkit A Resource for Parents with a Newly Diagnosed Child “Obstacles are the things we see when we take our eyes off our goals.” -Zig Ziglar EPILEPSY & MY CHILD TOOLKIT • TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Purpose .............................................................................................................................................5 How to Use This Toolkit ....................................................................................................................5 About Epilepsy What is Epilepsy? ..............................................................................................................................7 What is a Seizure? .............................................................................................................................8 Myths & Facts ...................................................................................................................................8 How is Epilepsy Diagnosed? ............................................................................................................9 How is Epilepsy Treated? ..................................................................................................................10 Managing Epilepsy How Can You Help Manage Your Child’s Care? ...............................................................................13 What Should You Do if Your Child has a Seizure? ............................................................................14 -

Epileptics Are Affected by Flashing Lights ~ Cutting-Edge Projects in 15 Countries Around Our Mission: Only the World in Their Search for a Cure

The REAL Project Research & Epilepsy Awareness Shona Sulzbach What is Epilepsy: What to do if you see someone having a seizure: - Epilepsy is a neurological disorder that presents - Time the seizure. itself in the form of a seizure. - Remain calm - A person must have more than one seizure to be - Stay with the person until the seizure ends and diagnosed with epilepsy. they are fully awake. - Epilepsy does not discriminate and 1/26 people - Comfort the person as they regain full will develop a seizure disorder in their life. Consciousness. Types of Epilepsy: Only call 911 if: - There are two broad categories: generalized - The person has not had a seizure before. and focal. - The seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes. - Not all seizures present themselves with the loss - The person is hurt during the seizure. of consciousness and convulsions. - The seizure occurred in water. - Many seizure disorders include types of seizures - The person has difficulty walking or breathing where the person goes into “a trance”. after the seizure ends. What is CURE? - The person has another seizure just after the What Causes Epilepsy: - Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy (CURE) first - Genetics, brain injury or trauma, and/or is a nonprofit organization that works to One. structural changes (tumors, growths, nerve promote epilepsy research. damage). - It was founded in 1998 by Susan Axelrod and a DO NOT: - About half of all people diagnosed with epilepsy small group of parents of children with - Hold the person down or try to stop the seizure. do not know the cause. epilepsy. - Try to open/put anything in the person’s mouth.