American Psychological Association 5Th Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles and Gases Such As Particulate Chemical Parameterizations in the Models (Carmichael Et Al., Matter (PM), Carbon Monoxide (CO), Ozone (O3), Nitrogen 2008)

Geosci. Model Dev., 13, 1055–1073, 2020 https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-1055-2020 © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Development of Korean Air Quality Prediction System version 1 (KAQPS v1) with focuses on practical issues Kyunghwa Lee1,2, Jinhyeok Yu2, Sojin Lee3, Mieun Park4,5, Hun Hong2, Soon Young Park2, Myungje Choi6, Jhoon Kim6, Younha Kim7, Jung-Hun Woo7, Sang-Woo Kim8, and Chul H. Song2 1Environmental Satellite Center, Climate and Air Quality Research Department, National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), Incheon, Republic of Korea 2School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Engineering, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology (GIST), Gwangju, Republic of Korea 3Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Texas, USA 4Air Quality Forecasting Center, Climate and Air Quality Research Department, National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), Incheon, Republic of Korea 5Environmental Meteorology Research Division, National Institute of Meteorological Sciences (NIMS), Jeju, Republic of Korea 6Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea 7Department of Advanced Technology Fusion, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of Korea 8School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea Correspondence: Chul H. Song ([email protected]) Received: 12 June 2019 – Discussion started: 18 July 2019 Revised: 30 January 2020 – Accepted: 5 February 2020 – Published: 10 March 2020 Abstract. For the purpose of providing reliable and robust compared with those of the CMAQ simulations without ICs air quality predictions, an air quality prediction system was (BASE RUN). For almost all of the species, the application developed for the main air quality criteria species in South of ICs led to improved performance in terms of correlation, Korea (PM10, PM2:5, CO, O3 and SO2). -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

2. Case Study: Anime Music Videos

2. CASE STUDY: ANIME MUSIC VIDEOS Dana Milstein When on 1 August 1981 at 12:01 a.m. the Buggles’ ‘Video Killed the Radio Star’ aired as MTV’s first music video, its lyrics parodied the very media pre- senting it: ‘We can’t rewind, we’ve gone too far, . put the blame on VTR.’ Influenced by J. G. Ballard’s 1960 short story ‘The Sound Sweep’, Trevor Horn’s song voiced anxiety over the dystopian, artificial world developing as a result of modern technology. Ballard’s story described a world in which natu- rally audible sound, particularly song, is considered to be noise pollution; a sound sweep removes this acoustic noise on a daily basis while radios broad- cast a silent, rescored version of music using a richer, ultrasonic orchestra that subconsciously produces positive feelings in its listeners. Ballard was particu- larly criticising technology’s attempt to manipulate the human voice, by con- tending that the voice as a natural musical instrument can only be generated by ‘non-mechanical means which the neruophonic engineer could never hope, or bother, to duplicate’ (Ballard 2006: 150). Similarly, Horn professed anxiety over a world in which VTRs (video tape recorders) replace real-time radio music with simulacra of those performances. VTRs allowed networks to replay shows, to cater to different time zones, and to rerecord over material. Indeed, the first VTR broadcast occurred on 25 October 1956, when a recording of guest singer Dorothy Collins made the previous night was broadcast ‘live’ on the Jonathan Winters Show. The business of keeping audiences hooked 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, promoted the concept of quantity over quality: yes- terday’s information was irrelevant and could be permanently erased after serving its money-making purpose. -

Political Leadership, Knowledge, and Socialization and Regional Environmental Cooperation in Northeast Asia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring August 2014 Still Dirty After All These Years: Political Leadership, Knowledge, and Socialization and Regional Environmental Cooperation in Northeast Asia Inkyoung Kim University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Inkyoung, "Still Dirty After All These Years: Political Leadership, Knowledge, and Socialization and Regional Environmental Cooperation in Northeast Asia" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 103. https://doi.org/10.7275/5534063.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/103 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STILL DIRTY AFTER ALL THESE YEARS: POLITICAL LEADERSHIP, KNOWLEDGE, AND SOCIALIZATION AND REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL COOPERATION IN NORTHEAST ASIA A Dissertation Presented by INKYOUNG KIM Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2014 Political Science © Copyright by Inkyoung Kim 2014 All Rights Reserved STILL DIRTY AFTER ALL -

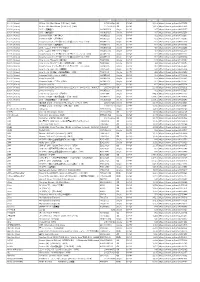

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert Nach Interpreten

Songliste Koreanisch (Juli 2018) Sortiert nach Interpreten SONGCODETITEL Interpret 534916 그저 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 534541 널 바라본것 뿐 1730 533552 MY WAY - 533564 기도 - 534823 사과배 따는 처녀 - 533613 사랑 - 533630 안녕 - 533554 애모 - 533928 그의 비밀 015B 534619 수필과 자동차 015B 534622 신인류의 사랑 015B 533643 연인 015B 975331 나 같은 놈 100% 533674 착각 11월 975481 LOVE IS OVER 1AGAIN 980998 WHAT TO DO 1N1 974208 LOVE IS OVER 1SAGAIN 970863기억을 지워주는 병원2 1SAGAIN/FATDOO 979496 HEY YOU 24K 972702 I WONDER IF YOU HURT LIKE ME 2AM 975815 ONE SPRING DAY 2AM 575030 죽어도 못 보내 2AM 974209 24 HOUR 2BIC 97530224소시간 2BIC 970865 2LOVE 2BORAM 980594 COME BACK HOME 2NE1 980780 DO YOU LOVE ME 2NE1 975116 DON'T STOP THE MUSIC 2NE1 575031 FIRE 2NE1 980915 HAPPY 2NE1 980593 HELLO BITCHES 2NE1 575032 I DON'T CARE 2NE1 973123 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 975236 I LOVE YOU 2NE1 980779 MISSING YOU 2NE1 976267 UGLY 2NE1 575632 날 따라 해봐요 2NE1 972369 AGAIN & AGAIN 2PM Seite 1 von 58 SONGCODETITEL Interpret 972191 GIVE IT TO ME 2PM 970151 HANDS UP 2PM 575395 HEARTBEAT 2PM 972192 HOT 2PM 972193 I'LL BE BACK 2PM 972194 MY COLOR 2PM 972368 NORI FOR U 2PM 972364 TAKE OFF 2PM 972366 THANK YOU 2PM 980781 WINTER GAMES 2PM 972365 CABI SONG 2PM/GIRLS GENERATION 972367 CANDIES NEAR MY EAR 2PM/백지영 980782 24 7 2YOON 970868 LOVE TONIGHT 4MEN 980913 YOU'R MY HOME 4MEN 975105 너의 웃음 고마워 4MEN 974215 안녕 나야 4MEN 970867 그 남자 그 여자 4MEN/MI 980342 COLD RAIN 4MINUTE 980341 CRAZY 4MINUTE 981005 HATE 4MINUTE 970870 HEART TO HEART 4MINUTE 977178 IS IT POPPIN 4MINUTE 975346 LOVE TENSION 4MINUTE 575399 MUZIK 4MINUTE 972705 VOLUME UP 4MINUTE 975332 WELCOME -

Universidade Federal Do Ceará Instituto De Cultura E Arte Curso De Design-Moda

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ INSTITUTO DE CULTURA E ARTE CURSO DE DESIGN-MODA RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL FORTALEZA 2019 RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL Monografia para o trabalho de conclusão de curso, em Design-Moda da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do título de graduado. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes FORTALEZA 2019 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará Biblioteca Universitária Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante aos dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a) A517k Amaral, Rafaela Prado do. Kpop: padrão de beleza, mídia e suas implicações no cotidiano dos grupos femininos na Coreia do Sul / Rafaela Prado do Amaral. – 2019. 61 f. : il. color. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (graduação) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Instituto de cultura e Arte, Curso de Design de Moda, Fortaleza, 2019. Orientação: Profa. Dra. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes . 1. Kpop. 2. Corpo. 3. Mídia. 4. Padrão de beleza. I. Título. CDD 391 RAFAELA PRADO DO AMARAL KPOP: PADRÃO DE BELEZA, MÍDIA E SUAS IMPLICAÇÕES NO COTIDIANO DOS GRUPOS FEMININOS NA COREIA DO SUL Monografia para o trabalho de conclusão de curso, em Design-Moda da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito para obtenção do título de graduado. Aprovada em: ___/___/______. BANCA EXAMINADORA ________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Francisca Raimunda Nogueira Mendes (Orientadora) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Cyntia Tavares Marques de Queiroz Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) _________________________________________ Profª. -

Lyrics-To-Audio Alignment by Unsupervised Discovery Of

FIRST DRAFT, 18 JANUARY 2017 1 Lyrics-to-Audio Alignment by Unsupervised Discovery of Repetitive Patterns in Vowel Acoustics Sungkyun Chang, Member, IEEE, and Kyogu Lee, Senior Member, IEEE Abstract—Most of the previous approaches to lyrics-to-audio 1) ASR-based: The core part of these systems [5]–[8] alignment used a pre-developed automatic speech recognition uses mature automatic speech recognition (ASR) techniques (ASR) system that innately suffered from several difficulties to developed previously for regular speech input. The phone adapt the speech model to individual singers. A significant aspect missing in previous works is the self-learnability of repetitive model is constructed as gender-dependent models through vowel patterns in the singing voice, where the vowel part used training with a large speech corpus [9]. In parallel, the music is more consistent than the consonant part. Based on this, our recordings are pre-processed by a singing voice separation system first learns a discriminative subspace of vowel sequences, algorithm to minimize the effect of unnecessary instrumental based on weighted symmetric non-negative matrix factorization accompaniment. In this situation, adapting the trained speech (WS-NMF), by taking the self-similarity of a standard acoustic feature as an input. Then, we make use of canonical time warping model to the segregated sung voice is a difficult problem, due (CTW), derived from a recent computer vision technique, to to the large variation in individual singing styles, remaining find an optimal spatiotemporal transformation between the accompaniments, and artifact noises. Based on the standard text and the acoustic sequences. Experiments with Korean and ASR technique, Fujihara, et al. -

Vanderbilt University Class of 2021 Commencement Program

VANDERBILT COMMENCEMENT 15–16 May 2021 Alma Mater On the city’s western border, reared against the sky, Proudly stands our Alma Mater as the years roll by. Forward! ever be thy watchword, conquer and prevail. Hail to thee, our Alma Mater, Vanderbilt, All Hail! Cherished by thy sons and daughters, memories sweet shall throng ’Round our hearts, O Alma Mater, as we sing our song. Forward! ever be thy watchword, conquer and prevail. Hail to thee, our Alma Mater, Vanderbilt, All Hail! —Robert F. Vaughan, 1907 The medallion on the cover of this program is the Official Seal of Vanderbilt University, adopted by the Board of Trust on May 4, 1875. II Progr am UNDERGRADUATE CEREMONY Procession of stage party starts at 9:00 a.m. Ceremonies on stage start around 9:07 a.m., end about noon. (Guests remain seated throughout the ceremony.) Processional (Banner Bearers, Deans, Founder’s Medalists, Faculty Senate Chair, Alumni Association President, Provost, Chair of Board of Trust, Chancellor) Rondeau Jean-Joseph Mouret Pomp and Circumstance Edward Elgar Trumpet Tune John Stanley Welcome Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Presentation of Emeriti Susan R. Wente, Provost Recognition of Other Academic Guests Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Awarding of Founder’s Medals for First Honors Susan R. Wente, Provost Presentation of Board of Trust Resolution Bruce R. Evans, Board of Trust Chair Farewell Remarks to Graduates Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Conferral of Degrees Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Musical Interlude Kingston Ho, violin, Class of 2023, Blair School of Music Danse Rustique Eugène Ysae Presentation of Graduates Alma Mater Ava Berniece Anderson, Class of 2021, Blair School of Music (Words on page II) Charge to the Graduates Daniel Diermeier, Chancellor Finale “Hoe-Down” from Rodeo Aaron Copland SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 VANDERBILT CAMPUS 1 Contents Te Academic Procession ......................................... -

CJ ENM Bloomberg: 035760 KS, Reuters: 035760.KS

Regional Company Focus CJ ENM Bloomberg: 035760 KS, Reuters: 035760.KS Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 9 Nov 2018 BUY, KRW219,000 KOSDAQ: 693.7 Strength in content business (Closing price as of 08/11/18) underpins earnings Price Target 12-mth: KRW300,000 • If not for IPTV commission hike, 3Q18 earnings would Reason for Report: 3Q18 earnings review have been a positive surprise Potential catalyst: Synergies between its digital channels and • To continue outperforming the market in terms of TV ad commerce business revenue growth Where we differ: We are more optimistic than the market for FY18F, but more conservative for FY19/20F • Commerce margins to recover in near term Analyst • Retain BUY, keep our TP of KRW300,000 Regional Research Team [email protected] Media: Stronger than expected TV and digital ad revenue. CJ ENM’s media division posted its highest-ever quarterly OP of KRW37.2bn (+305% y-o-y) in 3Q18. With the airing of premium content such as Price Relative ‘Boyfriend’ and ‘Memories of the Alhambra’ and several other 350,000 130 popular shows in 4Q18, CJ ENM’s TV ad revenue outperformance 300,000 120 250,000 110 and digital ad revenue growth should persist. Sales to Chinese and 100 200,000 global over-the-top (OTT) service providers also seem likely. 90 150,000 80 Commerce: Temporary dent to margins. Gross merchandise sales 100,000 70 50,000 60 were solid at KRW935.9bn (+5% y-o-y) with KRW80.2bn from T 0 50 commerce (+36% y-o-y) and KRW267.5bn from mobile commerce Nov-14 Jun-15 Jan-16 Aug-16 Mar-17 Oct-17 May-18 Stock price(LHS,KRW) Rel. -

Development of Korean Air Quality Prediction System Version 1

https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-2019-169 Preprint. Discussion started: 18 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Development of Korean Air Quality Prediction System 2 version 1 (KAQPS v1): an operational air quality 3 prediction system with focuses on practical issues 4 5 Kyunghwa Lee1,2, Jinhyeok Yu2, Sojin Lee3, Mieun Park4,5, Hun Hong2, Soon Young 6 Park2, Myungje Choi6, Jhoon Kim6, Younha Kim7, Jung-Hun Woo7, Sang-Woo Kim8 7 and Chul H. Song2* 8 9 1. Environmental Satellite Center, Climate and Air Quality Research Department, National 10 Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), Incheon, Republic of Korea 11 2. School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Engineering, Gwangju Institute of Science 12 and Technology (GIST), Gwangju, Republic of Korea 13 3. Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Texas, USA 14 4. Air Quality Forecasting Center, Climate and Air Quality Research Department, National 15 Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), Incheon, Republic of Korea 16 5. Environmental Meteorology Research Division, National Institute of Meteorological 17 Sciences (NIMS), Jeju, Republic of Korea 18 6. Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Yonsei University, Seoul, Republic of Korea 19 7. Department of Advanced Technology Fusion, Konkuk University, Seoul, Republic of 20 Korea 21 8. School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic 22 of Korea 23 24 25 Short title: Operational air quality prediction system in Korea 26 27 Corresponding author: Chul H. Song ([email protected]) 28 1 https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-2019-169 Preprint. Discussion started: 18 July 2019 c Author(s) 2019. -

Accel World . Altima.Burst the Gravity

ANIME Serie Tipo Artista/Titulo OP Arrival of Tears 11 eyes ENDING Asriel - Sequentia (TV) Accel World . OP Altima.Burst The Gravity (TV) Air ENDING Lia - Farewell Song (TV) OP Air TV - Tori no Uta [VIDEO] Akame ga Kill! ENDING Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta (TV) OP Sora Amamiya - Skyreach (TV) Aldnoah Zero. OP Kalafina - Heavenly blue (TV) Amnesia. OP Nagi Yanagi - Zoetrope (TV) Angel Beats ENDING Aoi Tada - Brave Song (TV) INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Answer Song INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Thousand Enemies OP Lia - My Soul, Your Beats (TV) Angelic Layer. OP Atsuko Enomoto - Be My Angel Anohana OP Galileo Galilei - Aoi Shiori OP Galileo Galilei - Circle Game (TV) Another. OP Another. Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen (TV) OP Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen Ao no exorcist ENDING 2PM - Take Off ENDING Meisa Kuroki - Wired Life (TV) OP ROOKiEZ is PUNK'D - In My World (TV) OP Uverworld - Core Pride (TV) Aoki Hagane no Arpeggio OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG (TV) ENDING Trident - Innocent Blue (TV) ENDING Trident - Blue Fields (TV) Arata Kangatari. OP Sphere - Genesis Aria (TV) OP Sphere - Genesis Aria Argevollen OP Kotoko - Tough Intention (TV) Arjuna ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba (TV) ENDING Maaya Sakamoto - Sanctuary (TV) Asu No Yoichi. OP Meg Rock - Egao No Riyuu (TV) Avenger op. OP Ali Project - Gesshoku Grand Guignol (TV) Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu end.Milktub – ENDING Baka Go Home (TV) Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Irohanihoheto OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten (TV) OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten Bakumatsu Rock OP vistlip - Jack (TV) Basilisk ENDING BasiliskNana Mizuki - Wild Eyes (TV) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (Full version) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (TV version) Beck OP Hit in USA Beelzebub ENDING 9nine - Shoujo Traveler (TV) ENDING no3b - Answer (TV) ENDING Shoko Nakagawa - Tsuyogari (TV) Black bullet .