Morotai—April 194 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council Chairs: Natalia Constantine Katie Hamlin Committee Topics: Topic 1: Nuclear Weapons in North Korea Topic 2: Syria Cessation of Hostilities Topic 3: Senkaku Islands Dispute 0 Chair Biographies Hello delegates! My name is Natalia Constantine and I’m in my senior year. I have been in MUN since 8th grade and this is my second time chairing, but my first time participating in Security Council. Besides MUN, I am on the tennis team, masque, and the school’s mathletics team. I am hoping for a fun and educational conference with resolutions passed, please do not hesitate in contacting me at [email protected] if you have any questions. See you all December 10th! Good day delegates! I am Katherine Hamlin, and I am a Junior this year at New Hartford High School. I have participated in MUN since I was in 8th grade and this will be my first time serving as a chair. Outside of MUN, I am also a distance swimmer for our school’s Varsity Swim team, a member of our French and Latin clubs, and a member of our Students for Justice and Equality club. I am greatly looking forward to serving as a chair on Security Council, and I hope that it will be an interesting and productive committee. If you have any questions, please contact me at [email protected] See you in December! Special Committee Notes Our simulation of the Security Council will be run Harvard Style. This means that there will be NO pre-written resolutions allowed in committee. -

Deconstructing Japan's Claim of Sovereignty Over the Diaoyu

Volume 10 | Issue 53 | Number 1 | Article ID 3877 | Dec 30, 2012 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Deconstructing Japan’s Claim of Sovereignty over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands 釣魚/尖閣に対する日本の統治権を脱構築 する Ivy Lee, Fang Ming “The near universal conviction in Japan with has shown effective control to be determinative which the islands today are declared an in a number of its rulings, a close scrutiny of ’integral part of Japan’s territory‘ is remarkable Japan’s effective possession/control reveals it to for its disingenuousness. These are islands have little resemblance to the effective unknown in Japan till the late 19th century possession/control in other adjudicated cases. (when they were identified from British naval As international law on territorial disputes, in references), not declared Japanese till 1895, theory and in practice, does not provide a not named till 1900, and that name not sound basis for its claim of sovereignty over the revealed publicly until 1950." GavanDiaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan will hopefully McCormack (2011)1 set aside its putative legal rights and, for the sake of peace and security in the region, start Abstract working with China toward a negotiated and mutually acceptable settlement. In this recent flare-up of the island dispute after Japan “purchased” three of theKeywords Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands, Japan reiterates its position that “the Senkaku Islands are an Diaoyu Dao, Diaoyutai, Senkakus, territorial inherent part of the territory of Japan, in light conflict, sovereignty, of historical facts and based upon international law.” This article evaluates Japan’s claims as I Introduction expressed in the “Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands”A cluster of five uninhabited islets and three published on the website of the Ministry of rocky outcroppings lies on the edge of the East Foreign Affairs, Japan. -

Q&A on the Senkaku Islands

Q&A on the Senkaku Islands Q1: What is the basic view of the Government of Japan on the Senkaku Islands? A1: There is no doubt that the Senkaku Islands are clearly an inherent territory of Japan, in light of historical facts and based upon international law. Indeed, the Senkaku Islands are under the valid control of Japan. There exists no issue of territorial sovereignty to be resolved concerning the Senkaku Islands. Q2: What are the grounds for Japan's territorial sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands? A2: 1. From 1885 on, surveys of the Senkaku Islands had been thoroughly made by the Government of Japan by the agencies of Okinawa Prefecture and by way of other methods. Through these surveys, it was confirmed that the Senkaku Islands had been uninhabited and showed no trace of having been under the control of the Qing Dynasty of China. Based on this confirmation, the Government of Japan made a Cabinet Decision on 14 January 1895 to erect a marker on the Islands to formally incorporate the Senkaku Islands into the territory of Japan. These measures were carried out in accordance with the ways of duly acquiring territorial sovereignty under international law. 2. Since then, the Senkaku Islands have continuously remained as an integral part of the Nansei Shoto which are the territory of Japan. These islands were neither part of the island of Formosa nor part of the Pescadores Islands which were ceded to Japan from the Qing Dynasty of China in accordance with Article 2 of the Treaty of Shimonoseki which came into effect in May of 1895. -

Paantu: Visiting Deities, Ritual, and Heritage in Shimajiri, Miyako Island, Japan

PAANTU: VISITING DEITIES, RITUAL, AND HERITAGE IN SHIMAJIRI, MIYAKO ISLAND, JAPAN Katharine R. M. Schramm Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Folklore & Ethnomusicology Indiana University December 2016 1 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ________________________ Michael Dylan Foster, PhD Chair ________________________ Jason Baird Jackson, PhD ________________________ Henry Glassie, PhD ________________________ Michiko Suzuki, PhD May 23, 2016 ii Copyright © 2016 Katharine R. M. Schramm iii For all my teachers iv Acknowledgments When you study islands you find that no island is just an island, after all. In likewise fashion, the process of doing this research has reaffirmed my confidence that no person is an island either. We’re all more like aquapelagic assemblages… in short, this research would not have been possible without institutional, departmental, familial, and personal support. I owe a great debt of gratitude to the following people and institutions for helping this work come to fruition. My research was made possible by a grant from the Japan Foundation, which accommodated changes in my research schedule and provided generous support for myself and my family in the field. I also thank Professor Akamine Masanobu at the University of the Ryukyus who made my institutional connection to Okinawa possible and provided me with valuable guidance, library access, and my first taste of local ritual life. Each member of my committee has given me crucial guidance and support at different phases of my graduate career, and I am grateful for their insights, mentorship, and encouragement. -

A Bird's Eye View of Okinawa

A Bird’s Eye View of Okinawa by HIH Princess Takamado, Honorary President ne of the most beautiful of the many O“must visit” places in Japan is the Ryukyu Archipelago. These islands are an absolute treasure trove of cultural, scenic and environmental discoveries, and the local people are known for their warmth and welcoming nature. Ikebana International is delighted to be able to host the 2017 World Convention in Okinawa, and I look forward to welcoming those of you who will be joining us then. 13 Kagoshima Kagoshima pref. Those who are interested in flowers are generally interested in the environment. In many cultures, flowers and birds go together, and so, Osumi Islands Tanega too, in my case. As well as being the Honorary President of Ikebana International, I am also the Yaku Honorary President of BirdLife International, a worldwide conservation partnership based in Cambridge, UK, and representing approximately 120 countries or territories. In this article, I Tokara Islands would like introduce to you some of the birds of Okinawa Island as well as the other islands in the Ryukyu Archipelago and, in so doing, to give you Amami a sense of the rich ecosystem of the area. Amami Islands Kikaiga One Archipelago, Six Island Tokuno Groups The Ryukyu Archipelago is a chain of islands Okinawa pref. Okino Erabu that stretches southwest in an arc from Kyushu (Nansei-shoto) to Chinese Taiwan. Also called the Nansei Islands, the archipelago consists of over 100 islands. Administratively, the island groups of Kume Okinawa Naha Osumi, Tokara and Amami are part of Kagoshima Prefecture, whilst the island groups Ryukyu Archipelago of Okinawa, Sakishima (consisting of Miyako Okinawa Islands and Yaeyama Islands), Yonaguni and Daito are part of Okinawa Prefecture. -

The Irabu Language and Its Speakers

Chapter 1 The Irabu language and its speakers This chapter introduces the language described in this grammar, Irabu Ryukyuan (henceforth Irabu). The chapter gives information about the ge- nealogical and geographical affi liations of the language together with the settlement and political history of the Rykukus. This chapter also addresses the sociolinguistic situation, literature review, and a brief sketch of import- ant features of phonology and grammar, with a particular focus on typolog- ical characteristics. 1.1. Geography Irabu is spoken on Irabu, which is one of the Sakishima Islands within the Ryukyu archipelago, an island chain situated in the extreme south of the Japan archipelago. Amami Islands Sakishima Islands Mainland Okinawa Ryukyu archipelago MAP 1 The Ryukyu archipelago The Sakishima Islands consist of two groups: the Miyako Islands and the Yaeyama Islands. Irabu is the second largest island in the Miyako Islands (MAP 2). 2 Chapter 1 Ikema Island Ogami Island Irabu Island Miyako Shimoji Island Island Tarama Island Kurima Island 5km 5mi MAP 2 The location of Irabu within the Miyako Islands1 Next to Irabu lies Shimoji, which has no permanent inhabitants and there is a very large airfi eld for training pilots and a small residential area of these pilots and associated people, surrounded by scattered fi elds of local people living in Irabu. However, this island used to be inhabited by lrabu people, and was called macїnaka [matsnaka] ‘in-the-woods’. The previous importance of this island as a living place is evidenced in the fact that it is the setting of a lot of stories and legends (see Appendix (1)). -

A General Overview of Irabu Ryukyuan, a Southern Ryukyuan Language of the Japonic Language Group1

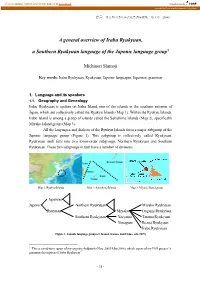

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Prometheus-Academic Collections 思言 東京外国語大学記述言語学論集 第 1 号(2006) A general overview of Irabu Ryukyuan, a Southern Ryukyuan language of the Japonic language group1 Michinori Shimoji Key words: Irabu Ryukyuan, Ryukyuan, Japonic languages, Japanese, grammar 1. Language and its speakers 1.1. Geography and Genealogy Irabu Ryukyuan is spoken on Irabu Island, one of the islands in the southern extreme of Japan, which are collectively called the Ryukyu Islands (Map 1). Within the Ryukyu Islands, Irabu Island is among a group of islands called the Sakishima Islands (Map 2), specifically Miyako Island group (Map 3). All the languages and dialects of the Ryukyu Islands form a major subgroup of the Japonic language group (Figure 1). This subgroup is collectively called Ryukyuan. Ryukyuan itself falls into two lower-order subgroups, Northern Ryukyuan and Southern Ryukyuan. These two subgroups in turn have a number of divisions. Map 1. Ryukyu Islands Map 2. Sakishima Islands Map 3. Miyako Island group Japanese Japonic Northern Ryukyuan Miyako Ryukyuan Ryuyuan Miyako Oogami Ryukyuan Southern Ryukyuan Yaeyama Tarama Ryukyuan Yonaguni Ikema Ryukyuan Irabu Ryukyuan Figure 1. Japonic language group (cf. Kamei, Koono, and Chino, eds. 1997) 1 This is a mid-term report of my ongoing fieldwork (Nov. 2005-May.2006), which is part of my PhD project “a grammar description of Irabu Ryukyuan”. - 31 - Michinori Shimoji 1.2. Previous studies on Irabu Ryukyuan The main focus of the previous studies on Irabu Ryukyuan has been on the phonetic/phonological aspects of that language. -

Watada, M., Amd M. Itoh

50 Research Notes DIS 82 (July 1999) s36-s37; Tomimura, Y., M. Matsuda, and Y.N. Tobari 1993, In: Drosophila ananassae. Genetical and Biological Aspects, (Tobari, Y.N., ed.), pp.139-151. Table 2. Number of strains with impatemate females in various species of the ananassae complex. No. of tested strains No. of strains with Speies Loclity (No. of females tested) impatemate females ananassae Nairobi, Kenya (L) 1 (17) 0 Kandy, Sri Lanka (C) 2 (61) 0 Coinbatore, India (D) 2 (59) 0 Hyderabad, India (HYD) 1 (21) 0 Bukit Timer, Singapore (W) 2 (73) 0 Chiang Mai, Thailand (B) 1 (27) 0 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (X) 2 (23) 0 Sandakan, Malaysia (S) 1 (10) 0 Palawa, Philppines (R) 1 (16) 0 Los Banos, Philippines (Q) 3(77) 0 Australia (AUS) 1 (25) 0 Guam (GUM) 2 (45) 0 Lae, Papua New Guinea (LAE) 1 (20) 0 Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea (POM) 2 (101) 0 Ponape, Caroline Islands (PNI) 2 (111) 0 Tongatapu, Tonga 1 (10) 0 Vava'u, Tonga (VAV) 1 (15) 0 Pago Pago, Samoa (PPG) 1 (41) 0 pal/idosa-Iike Wau, Papua New Guinea 2 (78) 0 Lae, Papua New Guinea 3(94) 1 pallidosa Lautoka, Fiji (NAN) 4 (162) 0 Taxon K Kotakinabalu, Malaysia 2 (69) 0 papuensis-Iike Wau, Papua New Guinea 2 (78) 0 Lae, Papua New Guinea 2 (43) 0 Strains, species, and symbol of locality were described in detail by Tomimura et al. (1993) Distrbution of Drosophila in Okinawa and Sakshima Islands, Japan. Watada, Masayoshi,1 and Masanobu Itoh.2 ¡Deparent of Biology and Earh Sciences, Faculty of Science, Ehime University, Matsuyama, Ehime 790-8577, Japan, and 2Deparent of Applied Biology, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Matsugasaki, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8585, Japan; Corresponding author: Masayoshi Watada, e-mail: watada(qgserv.g.ehime-u.ac.jp Distribution of Drosophila fles in six islands of Okinawa prefecture of Japan had been surveyed in 1980's and 1990's from ecological and biogeographical viewpoints. -

The U.S. Role in the Sino-Japanese Dispute Over the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands, 1945–1971*

The U.S. Role in the Sino-Japanese Dispute over the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands, 1945–1971* Jean-Marc F. Blanchard In 1996, the Sino-Japanese conflict over the Diaoyu (Senkaku) Islands intensified to the point where the American mass circulation periodical Time asked: “Will the next Asian war be fought over a few tiny islands?”1 That such a question could be asked seems incredible given that the Diaoyu Islands, which lie north-east of Taiwan and west of Okinawa, consist of only five small islands and three rocky outcroppings with a total landmass of no more than 7 square kilometres or 3 square miles.2 Apart from their miniscule size, the islands are uninhabited, are incapable of supporting human habitation for an extended period of time and are unlikely to support any economic life of their own from indigenous resources.3 Why do the Chinese and Japanese care so much about islands that one scholar noted “you can’t even find on most maps?”4 The main reason seems to be the desire to claim sovereignty over a huge area of the continental shelf and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), 71,000 square kilometres by one recent estimate, that would convey rights to almost 100 billion barrels of oil and rich fishing grounds.5 In addition, the islands are *I would like to thank Steven T. Benfell, Daniel Dzurek, Avery Goldstein, Akira Iriya, Walter A. McDougall, Phillip C. Saunders and Allen S. Whiting for their feedback on various drafts of this paper. I also would like to express my appreciation to the staff at the National Archives-College Park, particularly Greg Gluba, Rebecca L. -

Commissioned Research Report on the Senkaku Islands-Related Documents in Okinawa Prefecture

Commissioned Research Report on the Senkaku Islands-related documents in Okinawa Prefecture FY2014 Cabinet Secretariat Commissioned Research Project March 2015 Okinawa Peace Assistance Center Acknowledgements Okinawa Peace Assistance Center (OPAC) history, administrative history, and natural was founded in 2002 as a specified non-profit science. These references would be organization in pursuit of practicing the beneficial to shed light on the Okinawan “peace-seeking spirit of Okinawa.” OPAC people’s relations with the Senkaku Islands conduct various projects in international for further research. peace and security fields, ranging from We are in debt to many institutions in Table of Contents capacity building, cooperation and Okinawa. Our utmost gratitude goes to those assistance, research, and network building. who provided us the valuable opportunities Acknowledgements ……………………………2 In FY 2014, OPAC conducted a research for accessing the documents and materials. project, “the Senkaku Islands-related We also deeply appreciate the research Preface …………………………………………3 documents in Okinawa Prefecture,” committee members for their helpful Project Outline …………………………………5 commissioned by the Office of Policy confirmation on the material contents and Planning and Coordination on Territory and suggestions on policy methods. We also 1. Objectives and Summary ………………5 Sovereignty of Cabinet Office. The project thank for their valuable comments on the researched Senkaku-related documents and future course of Senkaku study. 2. Periodization ………………………………6 materials archived in Okinawa, and those references were cataloged and digitized for Reiji Fumoto, 3. Project Scheme and Processes…………7 easy access. Director, Okinawa Peace Assistance Center, The research covered the areas of local March 2015 4. Institutions …………………………………8 5. Research Results …………………………8 6. -

Aiming to Become a Natural World Heritage

ENGLISH To Be Listed as a Natural World Heritage Requires Maintaining and Conserving Universal Value Aiming to Become a Natural World Heritage The Natural Value of the Ryukyu Islands A Global Natural Treasure: The Ryukyu Islands —Recognizable and Therefore Protectable "Biodiversity" and "Ecosystem" as Reasons Objectives for Listing as a Natural World Heritage Site Japan's Last Undiscovered Region A Wondrous Forest The objective for gaining such listing is to protect and preserve a Iriomote Island Yambaru Region for Being Selected as a Candidate Site natural habitat that possesses outstanding universal value so that it In 2003, the Review Committee on Candidate Natural Sites for may be maintained as a heritage site for future generations. nomination to the World Heritage List (jointly established by the Ministry of the Environment and the Forestry Agency) selected the The Value of the Ryukyu Islands as a World Heritage Ryukyu Islands as a possible entrant from Japan. The Amami Island, Ecosystem Tokuno Island, the northern part of Okinawa Island (Yambaru), and Outstanding example of an ecosystem Iriomote Island in particular were lauded for their ecosystems and that clearly demonstrates a process of biodiversity. Despite the islands' geohistorical connection with the biological evolution independent from that Japanese mainland, the wildlife there have evolved independently and on a continental island diversified while endangered species live and grow in great numbers. Biodiversity The two most important factors when it comes to being listed as a An important region even from a global UNESCO Natural World Heritage site are to be of outstanding universal biodiversity-protection perspective for its value and for that value to be one that will be conserved for the future. -

Strategic Perspectives on the Sino-Japanese Dispute Over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands

A Segurança Marítima no Seio da CPLP: Contributos para uma Estratégia nos Mares da Lusofonia Strategic Perspectives on the Sino-Japanese Dispute over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands Tiago Alexandre Maurício Researcher at Kyoto University and WSD-Handa Felllow at Pacific Forum, CSIS, where is developing a project on Japan’s policy towards Senkaku/Diaoyu islands dispute. He is also a contributing analyst to Wikistrat, online consulting. He has an MA in War Studies from the King’s College (London), having previously graduated from the Technical University of Lisbon. Resumo Abstract Perspetivas Estratégicas sobre a Disputa Sino- Japonesa em Torno das Ilhas Diaoyu/Senkaku In recent years, but particularly in the last few months, we have seen growing media and scholarly attention fo- Nos últimos anos, mas particularmente nos últi‑ cusing on the dispute between Japan and the People´s mos meses, testemunhamos uma crescente atenção Republic of China in the East China Sea. The group of mediática e académica dedicada à disputa entre islands and rocks known as Senkaku in Japan, and Di- o Japão e a República Popular da China no Mar aoyu in China, has taken centre-stage in debates on the da China Oriental. O grupo de ilhas e rochedos evolution of the security environment in bilateral rela- conhecido como Senkaku no Japão, e Diaoyu na tions, as well as in the Asia-Pacific region writ large. China, tem assumido papel de relevo nos debates Looking at this dispute, one is struck not only by the sobre a evolução do ambiente securitário na rela‑ rapid changes occurring in the said security environ- ção bilateral, assim como na região Ásia‑Pacífico.