Underreporting COVID-19: the Curious Case of the Indian Subcontinent Cambridge.Org/Hyg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.Conference-APP Disaster Impact on Sundarbans

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Applied, Natural and Social Sciences (IMPACT: IJRANSS) ISSN(P): 2347-4580; ISSN(E): 2321-8851 Special Edition, Sep 2016, 5-12 © Impact Journals DISASTER IMPACT ON SUNDARBANS - A CASE STUDY ON SIDR AFFECTED AREA MOHAMMAD ZAKIR HOSSAIN KHAN Institute of Disaster Management and Vulnerability Studies, Dhaka University, Bangladesh ABSTRACT The primary indicators of environmental sustainability is the biodiversity and its conservation stated by Kates et al. (2001), whereas the assessment of biomass and floristic diversity in tropical forests has been identified as a priority by many international organizations stated by Stork et al. (1997). Cyclone ‘Sidr’, a tropical cyclone, was one of the biggest cyclones in the history of Bangladesh, formed in the central Bay of Bengal hit the coast of Bangladesh in 2007 and it made landfall on 15th of November with peaking wind speed of over 260 km/h. It resulted in an estimated 4,000 human deaths and the displacement of over 3 million people stated by US Embassy Dhaka (2007). The most significant devastating impact it left behind is on the diversity of flora of the Sundarbans. One quarter of the biomass cover (which is approximately 2500 sq. km) of the Sundarbans mangrove forest was damaged by the storm directly or indirectly due to the tidal surge stated by CEGIS (2007). The study shows that the total forest area damaged by the cyclone Sidr was about 21% of the Sundarbans. It was found that highly affected forest areas were dominated by Keora ( Sonneratia apetala ). Trees of Keora are comparatively taller more than 15 m and grow on newly accreted forest land. -

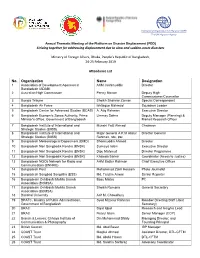

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving Together for Addressing Displacement Due to Slow and Sudden-Onset Disasters

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving together for addressing displacement due to slow and sudden-onset disasters Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dhaka, People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 24-25 February 2019 Attendance List No. Organization Name Designation 1 Association of Development Agencies in AKM Jashimuddin Director Bangladesh (ADAB) 2 Australian High Commission Penny Morton Deputy High Commissioner/Counsellor 3 Bangla Tribune Sheikh Shahriar Zaman Special Correspondent 4 Bangladesh Air Force Ishtiaque Mahmud Squadron Leader 5 Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) A. Atiq Rahman Executive Director 6 Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, Prime Ummay Salma Deputy Manager (Planning) & Minister's Office, Government of Bangladesh Market Research Officer 7 Bangladesh Institute of International and Munshi Faiz Ahmad Chairman Strategic Studies (BIISS) 8 Bangladesh Institute of International and Major General A K M Abdur Director General Strategic Studies (BIISS) Rahman, ndc, psc 9 Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) Shamsuddin Ahmed Director 10 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Sumaiya Islam Executive Director 11 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Dipu Mahmud Director Programme 12 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Khaleda Sarkar Coordinator (Acess to Justice) 13 Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and AHM Bazlur Rahman Chief Executive Officer Communication (BNNRC) 14 Bangladesh Post Mohammad Zakir Hossain Photo Journalist 15 Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) Md. Tanzim Anwar -

Chapter 1 Introduction Main Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Main Report Chapter 1 Introduction Main Report CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study The Peoples Republic of Bangladesh has a population of 123 million (as of June 1996) and a per capita GDP (Fiscal Year 1994/1995) of US$ 235.00. Of the 48 nations categorized as LLDC, Bangladesh is the most heavily populated. Even after gaining independence, the nation repeatedly suffers from floods, cyclones, etc.; 1/3 of the nation is inundated every year. Shortage in almost all sectors (e.g. development funds, infrastructure, human resources, natural resources, etc.) also leaves both urban and rural regions very underdeveloped. The supply of safe drinking water is an issue of significant importance to Bangladesh. Since its independence, the majority of the population use surface water (rivers, ponds, etc.) leading to rampancy in water-borne diseases. The combined efforts of UNICEF, WHO, donor countries and the government resulted in the construction of wells. At present, 95% of the national population depend on groundwater for their drinking water supply, consequently leading to the decline in the mortality rate caused by contagious diseases. This condition, however, was reversed in 1990 by problems concerning contamination brought about by high levels of arsenic detected in groundwater resources. Groundwater contamination by high arsenic levels was officially announced in 1993. In 1994, this was confirmed in the northwestern province of Nawabganji where arsenic poisoning was detected. In the province of Bengal, in the western region of the neighboring nation, India, groundwater contamination due to high arsenic levels has been a problem since the 1980s. -

Indo-Bangladesh Relations

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 7 Nos.3-4 July - December 2003 BANGLADESH SPECIAL Regimes, Power Structure and Policies in Bangladesh Redwanur Rahman Indo-Bangladesh Relations Anand Kumar India-Bangladesh Bilateral Trade: Issues and Concerns Indra Nath Mukherji Rise of Religious Radicalism in Bangladesh Apratim Mukarji Hindu Religious Minority in Bangladesh Haridhan Goswami and Zobaida Nasreen Situation of Minorities in Bangladesh Ruchira Joshi Conflict and the 1997 Peace Accord of Chittagong Hill Tracts Binalakshmi Nepram Demographic Invasion from Bangladesh Bibhuti Bhusan Nandy India and Bangladesh: The Border Issues Sreeradha Datta Bangladesh-Pakistan Relations Smruti S. Pattanaik HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K. WARIKOO Assistant Editor : SHARAD K. SONI © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 200.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 400.00 Institutions : Rs. 500.00 & Libraries (Annual) OVERSEAS (AIRMAIL) Single Copy : US $ 15.00 UK £ 10.00 Annual (Individual) : US $ 30.00 UK £ 20.00 Institutions : US $ 50.00 & Libraries (Annual) UK £ 35.00 The publication of this journal (Vol.7, Nos.3-4, 2003) has been financially supported by the Indian Council of Historical Research. -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Freemuse-Drik-PEN-International

Joint submission to the mid-term Universal Periodic Review of Bangladesh by Freemuse, Drik, and PEN International 4 December 2020 Executive summary Freemuse, Drik, and PEN International welcome the opportunity to contribute to the mid-term review of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) on Bangladesh. This submission evaluates the implementation of recommendations made in the previous UPR and assesses the Bangladeshi authorities’ compliance with international human rights obligations with respect to freedoms of expression, information and peaceful assembly, in particular concerns related to: - Digital Security Act and Information and Communication Technology Act - Limitations on freedom of religion and belief - Restrictions to the right to peaceful assembly and political engagement - Attacks on artistic freedom and academic freedom As part of the third cycle UPR process in 2018, the Government of Bangladesh accepted 178 recommendations and noted 73 out of a total 251 recommendations received. This included some aimed at guaranteeing the rights to freedom of expression, information and peaceful assembly. However, a crackdown on freedom of expression has been intensified since the review and civil society, including artists and journalists, has faced adversity from authorities. These are in violation of Bangladesh’s national and international commitments to artistic freedom, specifically the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which were ratified by the authorities in 2000 and 1998, respectively. This UPR mid-term review was compiled based on information from Freemuse, Drik and PEN International. 1 SECTION A Digital Security Act: a threat to freedom of expression Third Cycle UPR Recommendations The Government of Bangladesh accepted recommendations 147.67, 147.69, 147.70, 148.3, 148.13, 148.14, and 148.15 concerning the Information and Communication Technology Act and Digital Security Act. -

Music Industry Workshop

Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries Proceedings of the Youth Forum MUSIC INDUSTRY WORKSHOP European Parliament Brussels, Belgium 19 May 2001 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2003 NOTE The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All data are provided without warranty of any kind and the United Nations does not make any representation or warranty as to their accuracy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purposes. UNCTAD/LDC/MISC.82 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication is the outcome of the proceedings of the Youth Forum Music Industry Workshop, a parallel event organized on 19 May 2001 during the Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries, held in the European Parliament in Brussels. Ms. Zeljka Kozul-Wright, the Youth Forum Coordinator of the Office of the Special Coordinator for LDCs, prepared this publication. Lori Hakulinen-Reason and Sylvie Guy assisted with production and Diego Oyarzun-Reyes designed the cover. ii CONTENTS Pages OPENING STATEMENTS Statement by Mr. Rubens Ricupero ............................................................................ 1 Statement by H.E. Mr. Mandisi B. Mpahlwa ............................................................... 5 Statement by Ms. Zeljka Kozul-Wright......................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Challenges and prospects in the music industry for developing countries by Zeljka Kozul-Wright................................................................................................. -

Concert for Migrants’ at a Glance: to Celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a Virtual Concert Titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ Was Organized on 18 December 2020

‘Concert for Migrants’ at A Glance: To celebrate International Migrants Day 2020, a virtual concert titled ‘Concert for Migrants’ was organized on 18 December 2020. Featuring popular singers from home and abroad, the concert has reached more than 3.3 million people in more than 30 countries worldwide. In between performing a range of popular songs, the celebrities spoke on the importance of informed migration decisions contributing to regular, safe, and orderly migration, sustainable reintegration as well as migration governance. Outreach of the Concert Number of people reached online 1.9 Million Number of people watched the concert on TV 1.4 Million Total 3.3 Million Name of the top 15 countries from where Bangladesh, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Qatar, Lebanon, Kuwait, people watched the concert Bahrain, Jordan, Malaysia, Singapore, UK, Egypt, Italy, and Japan Number of media report produced 37+ A number of creative content were developed and shared on our social media platforms with the endorsement of celebrities. Video messages of the singers: • Fahmida Nabi: https://fb.watch/2Nh7wL_j-c/ • Sania Sultana Liza: https://fb.watch/2Nh5OeaFrB/ • S.I. Tutul: https://fb.watch/2Nh6HEtrjW/ • Sahos Mostafiz: https://fb.watch/2NhdDW4VBj/ • Fakir Shabuddin: https://fb.watch/2NhavHLAXI/ • Xefer Rahman: https://fb.watch/2NhfsHFkb2/ • Polash Noor: https://fb.watch/2Nh3fURc-Z/ • Nowshad Ferdous: https://fb.watch/2NhgfU2SfA/ • Mizan Mahmud Razib: https://fb.watch/2Nh9_iwehf/ Promo: https://fb.watch/2NhcsD5lRB/ Media Reports on the Concert: 1. Daily Star 11. Daily Asian Age 21. Dainik Amader Shomoy 31. Barta 24 2. Dhaka Tribune 12. Daily Ittefaq 22. Newshunt 32. Change 24 3. -

Media Coverage Links

Pneumonia in Bangladesh: Where we are and what need to do Media Coverage Links 1. icddr,b press release - https://www.icddrb.org/quick-links/press-releases?id=98&task=view 2. UNB (news agency) - http://www.unb.com.bd/category/Bangladesh/pneumonia-kills-24000- plus-children-in-bangladesh-every-year/60359 3. The Daily Star - https://www.thedailystar.net/city/news/juvenile-pneumonia-ignored-due- covid-pandemic-experts-1993417 4. Dhaka Tribune (English) https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2020/11/11/every-hour- pneumonia-kills-3-children-in-bangladesh 5. Dhaka Tribune (Bangla) https://bit.ly/3ngKe2H 6. The New Age - https://www.newagebd.net/article/121327/67-children-die-of-pneumonia- daily:-study 7. The Observer BD - https://www.observerbd.com/news.php?id=284093 8. The Business Standard - https://tbsnews.net/bangladesh/health/67-children-die-pneumonia- every-day-bangladesh-156727 9. The Financial Express - https://www.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/health/pneumonia-kills-67- children-every-day-in-bangladesh-1605157926 10. The Independent - http://www.theindependentbd.com/post/255893 11. Bangladesh Post (print and online – English) - https://www.bangladeshpost.net/posts/pneumonia-still-number-one-killer-of-bangladeshi- children-46768 12. The Daily Sun (print and online – English) - https://www.daily- sun.com/post/517196/Preventing-child-death-from-pneumonia-requires-multi-system-approach 13. The New Nation (print and online – English) - http://thedailynewnation.com/news/268690/67-children-die-of-pneumonia-every-day-in- bangladesh.html 14. The Bangladesh and Beyond (online – English) - https://thebangladeshbeyond.com/preventing- child-death-from-pneumonia-requires-multi-system-approach-health-experts/ 15. -

Ganges Strategic Basin Assessment

Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 67668-SAS Report No. 67668-SAS Ganges Strategic Basin Assessment A Discussion of Regional Opportunities and Risks Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized GANGES STRATEGIC BASIN ASSESSMENT: A Discussion of Regional Opportunities and Risks b Report No. 67668-SAS Ganges Strategic Basin Assessment A Discussion of Regional Opportunities and Risks Ganges Strategic Basin Assessment A Discussion of Regional Opportunities and Risks World Bank South Asia Regional Report The World Bank Washington, DC iii GANGES STRATEGIC BASIN ASSESSMENT: A Discussion of Regional Opportunities and Risks Disclaimer: © 2014 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 14 13 12 11 This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law.