Bangladesh: Journalists, the Press and Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Study on Violence Against Children Response to The

United Nations Study on Violence against Children Response to the questionnaire received from the Government of BANGLADESH QUESTIONNAIRE I. Legal Framework This part of the questionnaire aims to determine how your country's legal framework addresses violence against children, including prevention of violence, protection of children from violence, redress for victims of violence, penalties for perpetrators and reintegration and rehabilitation of victims. International human rights instruments 1. Describe any developments with respect to violence against children, which have resulted from your country's acceptance of international human rights instruments, including, for example, the convention of the Rights of the Child and its optional protocols, the Palermo Protocol or regional human rights instruments. Provide information on cases concerning violence against children in which your country's courts or tribunals have referred to international or regional human rights standards. Answer 1: The Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh was among the first country to ratify the United Nations Convention on the rights of the child (CRC) in 1990. As a signatory to the CRC and its protocol the Government of Bangladesh has made various efforts towards implementing the provision of the CRC. The Government has taken prompt action to disseminate the CRC to the stakeholder i.e. policy makers, elected public representatives at grass root level and to the civil society member to aware them about the right of the children. To implement the CRC the government had formed a core group after signing of the CRC and its optional protocol. The esteem Ministry is maintaining a database on violence against children of the country. -

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020

Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Supported by Published by I Bangladesh Workplace Death Report 2020 Published by Safety and Rights Society 6/5A, Rang Srabonti, Sir Sayed Road (1st floor), Block-A Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207 Bangladesh +88-02-9119903, +88-02-9119904 +880-1711-780017, +88-01974-666890 [email protected] safetyandrights.org Date of Publication April 2021 Copyright Safety and Rights Society ISBN: Printed by Chowdhury Printers and Supply 48/A/1 Badda Nagar, B.D.R Gate-1 Pilkhana, Dhaka-1205 II Foreword It is not new for SRS to publish this report, as it has been publishing this sort of report from 2009, but the new circumstances has arisen in 2020 when the COVID 19 attacked the country in March . Almost all the workplaces were shut about for 66 days from 26 March 2020. As a result, the number of workplace deaths is little bit low than previous year 2019, but not that much low as it is supposed to be. Every year Safety and Rights Society (SRS) is monitoring newspaper for collecting and preserving information on workplace accidents and the number of victims of those accidents and publish a report after conducting the yearly survey – this year report is the tenth in the series. SRS depends not only the newspapers as the source for information but it also accumulated some information from online media and through personal contact with workers representative organizations. This year 26 newspapers (15 national and 11 regional) were monitored and the present report includes information on workplace deaths (as well as injuries that took place in the same incident that resulted in the deaths) throughout 2020. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Trans-boundary elected representative workshop on Challenges and Management of Public Disclosure Authorized Sundarbans Landscape: Finding a Shared Way Forward on Sundarbans On MV Paramhansa Cruise; 20 – 22 March, 2015 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Background ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Objectives of the event .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3. Scope of the event ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. Background for the event .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Assessment of current situation .................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1. Key issues and challenges ............................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2. Current perception of key stakeholders ......................................................................................... 7 2.1.3. Possible problem solving approaches -

Article 19: Freedom of Opinion and Expression

Article 19: Freedom of Opinion and Expression Why would a human rights organization go to court to support someone whose extreme political views or ethical position it fundamentally opposes? A pornographer perhaps, or an anarchist? Because of the rights asserted in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), we all have the right to form our own opinions and to express and share them freely. “If we do not believe in freedom of expression “The first human who hurled an for people we despise, we do not believe in it at insult instead of a stone was the all,” says linguist and political activist Noam founder of civilization.” Chomsky. Adds Human Rights Watch: –Sigmund Freud “freedom of speech is a bellwether: how any society tolerates those with minority, disfavored or even obnoxious views will often speak to its performance on human rights more generally.” This right underpins many others, such as religion, assembly and the ability to participate in public affairs, but freedom of expression is not unlimited. A common metaphor to describe its limits is that you cannot falsely yell “fire” in a crowded theatre and cause a panic and possible injury. Other forms of speech generally not protected include child pornography, perjury, blackmail, and incitement to violence. The UDHR’s drafters wrestled with the issue of how tolerant a tolerant society should be of people like Nazis and fascists who themselves are intolerant. They were acutely conscious of the role played by the Nazi media and film industry in the creation of an environment that enabled the slaughter of 6 million Jews, and other groups such as the Roma and people with disabilities. -

Media Analysis Report: Nutrition and Health Issues in the Media

Media Analysis Report: Nutrition and Health Issues in the Media April 2014 Conducted by Supported by This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Health, Infectious Diseases, and Nutrition, Bureau for Global Health, and USAID/Bangladesh under terms of Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-12-00005, through the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance III (FANTA) Project, managed by FHI 360. The contents are the responsibility of FHI 360 and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Background ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Objective of the Media Analysis .............................................................................................................. 1 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Results of Print Media Monitoring ........................................................................................................... 4 Results of Broadcast Media Monitoring ................................................................................................ 10 Comparative Analysis of Baseline and Follow-Up Media Monitoring ................................................... 14 Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................................................... -

Joint Letter to the Human Rights Council Calling for States' Action To

www.amnesty.org AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC STATEMENT DATE 17 June 2021 INDEX MDE 28/4303/2021 JOINT LETTER TO THE HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL CALLING FOR STATES’ ACTION TO ADDRESS THE ALGERIAN AUTHORITIES’ ALARMING CRACKDOWN ON PRO-DEMOCRACY FORCES 82 civil society organisations call on states to take action to address the Algerian authorities' alarming crackdown on pro- democracy forces during HRC 47 The unrelenting criminalisation of fundamental freedoms warrants an urgent response Dear representatives, We, the undersigned Algerian, regional and international non-governmental organisations, urge your government, individually and jointly with other states, to address the alarming crackdown on peaceful Algerian protesters, journalists, civil society members and organisations, human rights defenders and trade unionists during the 47th United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC) session. Repression has increased drastically and a more assertive public position from states is crucial to protecting Algerians peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly. We urge you, in relevant agenda items such as in the interactive dialogue with the High Commissioner under Item 2 or in the Interactive Debates with the Special Rapporteurs on freedom of expression and freedom of association and peaceful assembly under Item 3, to: ● Condemn the escalating crackdown on peaceful protesters, journalists and human rights defenders, including the excessive use of force, the forced dispersal and intimidation of protesters and the -

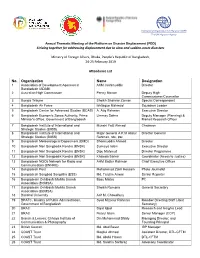

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving Together for Addressing Displacement Due to Slow and Sudden-Onset Disasters

Annual Thematic Meeting of the Platform on Disaster Displacement (PDD) Striving together for addressing displacement due to slow and sudden-onset disasters Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dhaka, People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 24-25 February 2019 Attendance List No. Organization Name Designation 1 Association of Development Agencies in AKM Jashimuddin Director Bangladesh (ADAB) 2 Australian High Commission Penny Morton Deputy High Commissioner/Counsellor 3 Bangla Tribune Sheikh Shahriar Zaman Special Correspondent 4 Bangladesh Air Force Ishtiaque Mahmud Squadron Leader 5 Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies (BCAS) A. Atiq Rahman Executive Director 6 Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority, Prime Ummay Salma Deputy Manager (Planning) & Minister's Office, Government of Bangladesh Market Research Officer 7 Bangladesh Institute of International and Munshi Faiz Ahmad Chairman Strategic Studies (BIISS) 8 Bangladesh Institute of International and Major General A K M Abdur Director General Strategic Studies (BIISS) Rahman, ndc, psc 9 Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) Shamsuddin Ahmed Director 10 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Sumaiya Islam Executive Director 11 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Dipu Mahmud Director Programme 12 Bangladesh Nari Sangbadik Kendra (BNSK) Khaleda Sarkar Coordinator (Acess to Justice) 13 Bangladesh NGOs Network for Radio and AHM Bazlur Rahman Chief Executive Officer Communication (BNNRC) 14 Bangladesh Post Mohammad Zakir Hossain Photo Journalist 15 Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) Md. Tanzim Anwar -

Kenya: ARTICLE 19 Calls for Expansion of Freedom of Expression Rights to Be Integrated Into the New Draft Constitution of Kenya

For immediate release – 15 May 2009 Kenya: ARTICLE 19 Calls for Expansion of Freedom of Expression Rights to be Integrated into the New Draft Constitution of Kenya Today, ARTICLE 19 Kenya and East Africa, based in Nairobi, Kenya, submitted its comments to the Committee of Experts for the new Constitutional Review Process currently ongoing in Kenya. ARTICLE 19 welcomes the review process and calls on the Committee of Experts to ensure the new Draft Constitution of Kenya is in line with freedom of expression and information best practice and international standards, as laid out in Article 19 of the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Kenya has signed and ratified. The Constitutional Review Process seeks to improve the current Constitution of Kenya which was first developed in 1963, and amended in 1996. The current process to review the Constitution will be the third of its kind. The Committee of Experts is responsible for developing a new draft Constitution by 1 December 2009. The final draft is expected to be adopted by Parliament by 2 March 2010 prior to a constitutional referendum. In its note to the Committee of Experts, ARTICLE 19 highlights the areas where guarantee of freedom of expression falls short of international human rights law and standards on the right to freedom of expression, the right to access information, and media freedoms. ARTICLE 19’s recommendations to the Committee of Experts include: That the Committee should ensure that the new Draft Constitution of Kenya protects the right of freedom of expression, including the right to information, in compliance with international and regional human rights law and standards. -

A Legacy of Virtue the Government Can't Silence: The

A Legacy of Virtue the Government Can’t Silence: The Case of Shahidul Alam The job for media pundits and intellectuals is often to question black and white narratives that are, in reality; washed in greys. But there are other times when things aren’t so complicated. There are times when one side clearly stands for inclusivism, creativity, empathy, mercy, mirth, humor, compassion and an unabashed zeal for the act of living, while the other side represents grim, cynical, self-interested raw power perpetuated by those who use violence to cover their insecurities, fears and incapacity to see that one’s reason for living on this earth has nothing to do with the allure of power and control. The arrest of renowned photographer Shahidul Alam by the Bangladeshi government is one these times. Alam, 63, was detained on Aug. 5, 2018, by plain-clothed officers who identified themselves as the detective branch of the Bangladeshi government. He was charged under the Section 57 Information and Communication Technology Act (ICT) with “spreading propaganda and false information used against a government” and for making “provocative comments” about the government’s violent response to students protesting for safer roads, in an interview he conducted with Al Jazeera. He was arrested hours after the interview. Bangladeshi’s ruling government, the Awami League, has consistently used Section 57 as a legal bludgeon to silence critics. The Bangladeshi court rejected Alam’s bail plea on Sept. 11 and he remains imprisoned. The protests, which started in Dhaka but spread throughout the country, began after a private bus ran over a group of college students, killing two. -

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of Valid Candidates for the Post of "Cashier"

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of valid candidates for the post of "Cashier" Sl. No Tracking No Roll Name Father's Name 1 1710040000000003 16638 MD. ZHAHIDUL ISLAM SHAHIN MD. SAIFUL ISLAM 2 1710040000000006 13112 MD. RATAN ALI MD. EBRAHIM SARKAR 3 1710040000000007 09462 TANMOY CHAKRABORTY BHIM CHAKRABORTY 4 1710040000000008 01330 MOHAMMAD MASUDUR LATE MOHAMMAD CHANDMIAH RAHMAN MUNSHI 5 1710040000000009 17715 SUSMOY. NOKREK ASHOK.CHIRAN 6 1710040000000012 14054 OMAR FARUK MD. GOLAM HOSSAIN 7 1710040000000013 17910 MD. BABAR UDDIN ANSARUL HOQ 8 1710040000000015 13444 SHAKIL JAINAL ABEDIN 9 1710040000000016 19905 ASIM BISWAS ANIL CHANDRA BISWAS 10 1710040000000017 21002 MD.MAHMUDUL HASAN MD.RAFIQUL ISLAM 11 1710040000000019 19973 MD.GOLAM SOROWER MD. SHOHRAB HOSSIN 12 1710040000000020 19784 MD ROKIBUL ISLAM MD OHIDUR RAHMAN 13 1710040000000021 17365 MD. SAIFUL ISLAM MOHAMMAD ALI 14 1710040000000022 17634 MD. ABUL KALAM AZAD MD. KARAMAT ALI 15 1710040000000023 04126 ZAHANGIR HOSSAIN MOHAMMAD MOLLA 16 1710040000000028 03753 MD.NURUDDIN MD.AMIR HOSSAIN 17 1710040000000029 20472 MD.SHAH EMRAN MD.SHAH ALAM 18 1710040000000030 08603 ANUP KUMAR DAS BIREN CHANDRA DAS 19 1710040000000031 14546 MD. FAISAL SHEIKH. MD. ARMAN SHEIKH. 20 1710040000000035 14773 MD. ARIFUL ISLAM MD. SHAHAB UDDIN 21 1710040000000037 13897 SHAKIL AHMED MD. NURUL ISLAM 22 1710040000000039 06463 MD. PARVES HOSSEN MD. SANA ULLAH 23 1710040000000042 19254 MOHAMMAD TUHIN SHEIKH MOHAMMAD TOMIZADDIN SHEIKH 24 1710040000000043 15792 MD. RABIUL HOSSAIN MD. MAHBUBAR RAHMAN 25 1710040000000047 00997 ANJAN PAUL AMAL PAUL 26 1710040000000048 16489 MAHBUB HASAN MD. AB SHAHID 27 1710040000000049 05703 MD. PARVEZ ALAM MD. SHAH ALAM 28 1710040000000051 10029 MONIRUZZAMAN MD.HABIBUR RAHMAN 29 1710040000000052 18437 SADDAM HOSSAIN MOHAMMAD ALI 30 1710040000000053 07987 MUSTAK AHAMMOD ABU AHAMED 31 1710040000000057 14208 MD. -

Media Monitoring Report June 2020

Media Monitoring Report June 2020 Prepared for Bangladesh Health Watch Prepared by Media Professionals Group 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS Newspapers Monitoring Report at a glance Introduction: Media Reality in Bangladesh Newspapers Mentoring Methodology Findings Newspaper Coverage Scenario of Health Issues 1. Issues covered by Newspapers 2. Publication overview Coverage of Health Issues Interactive Journalism and Citizen Journalism 3. Summary Observations Annexure 2 | P a g e Newspapers Monitoring Report at a glance Most of Journalists are still working from home. Virtual communication is the main way to collect information. But printing copies of newspapers have been reaching to more readers now than last month due to open of transportation. On the other hand, public and private offices are working with limited facilities and manpower in National and local level. Main focuses of Government activities are health services and relief distribution. Newspapers have been trying to update readers Coronavisrus related issues in different dimensions considering plans, performances and gaps. All six newspaper (Prothom Alo, Samakal, Kalerkantho, Bangla Tribune, Daily Star and New Age) have been addressing similar issues every day. But they are maintaining their own style of presentation. Prothom Alo and Daily Star are little ahead compare to others. Journalists’ leaders have been raising voices against retrenchment, salary cut and salary nonpayment of journalists by media authorities. Due to long holidays as well as pandemic related abnormal situation media authorizes have been losing their income in terms of selling newspapers and advertisements. So issues of health safety and survival both are making journalists panic and creating disturbances for demonstrating their deserved professional performances A list of issues are identified which were frequently covered during this period. -

English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh

Advances in Journalism and Communication, 2016, 4, 127-148 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajc ISSN Online: 2328-4935 ISSN Print: 2328-4927 Small Circulation, Big Impact: English Language Newspaper Readability in Bangladesh Jude William Genilo1*, Md. Asiuzzaman1, Md. Mahbubul Haque Osmani2 1Department of Media Studies and Journalism, University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2News and Current Affairs, NRB TV, Toronto, Canada How to cite this paper: Genilo, J. W., Abstract Asiuzzaman, Md., & Osmani, Md. M. H. (2016). Small Circulation, Big Impact: Eng- Academic studies on newspapers in Bangladesh revolve round mainly four research lish Language Newspaper Readability in Ban- streams: importance of freedom of press in dynamics of democracy; political econo- gladesh. Advances in Journalism and Com- my of the newspaper industry; newspaper credibility and ethics; and how newspapers munication, 4, 127-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2016.44012 can contribute to development and social change. This paper looks into what can be called as the fifth stream—the readability of newspapers. The main objective is to Received: August 31, 2016 know the content and proportion of news and information appearing in English Accepted: December 27, 2016 Published: December 30, 2016 language newspapers in Bangladesh in terms of story theme, geographic focus, treat- ment, origin, visual presentation, diversity of sources/photos, newspaper structure, Copyright © 2016 by authors and content promotion and listings. Five English-language newspapers were selected as Scientific Research Publishing Inc. per their officially published circulation figure for this research. These were the Daily This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Star, Daily Sun, Dhaka Tribune, Independent and New Age.