Study of Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions and Beliefs Regarding HIV and AIDS (KAPB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES Centre: Provincial Office, Nelspruit Salary: R1 185 879 – 1 355 916 P.A

MPUMALANGA PROVINCE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH “SIYANAKEKELA” SENIOR MANAGER: PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES Centre: Provincial Office, Nelspruit Salary: R1 185 879 – 1 355 916 p.a. (OSD Requirements). All shortlisted candidates for SMS posts will be subjected to a technical exercise that intends to test relevant technical elements of the job. The recommended candidates will be subjected to a competency assessment. The successful candidate must sign a performance agreement. Reference No: MPDoH/July/17/01 Requirements: Diploma Pharm / BSC. Pharm / B. Pharm or NQF Level 7 qualification as recognized by SAQA. Current registration with SAPC. At least five (5) years of experience at a middle / senior managerial level. Good communication, interpersonal and computer skills (MS Word and Excel). Ability to work in a team. Good understanding of the National Drug Policy and good pharmacy practice guidelines. Sound knowledge of the Pharmacy Act and the related Substance Act. A valid code B driver’s license. Duties: Development of strategic and operational plan of Pharmaceutical services. Compile annual quarterly and monthly reports of Pharmaceutical services. Management of the pharmaceutical budget and monitor expenditure. Overall responsibility and accountability for medicine supply management processes. Manage warehousing of all pharmaceuticals. Manage the development and review of pharmaceutical policies. Manage Essential Medicine List Programme. Render technical and pharmaceutical support to all health programmes. Provide expert advice and training to other healthcare. Ensure the implementation of the down referral system. Implement the essential drug Programme. Supervise pharmaceutical care to Hospital patients by implementing monitoring of work procedures, policies and Guidelines. Overall responsibility and accountability for drug supply management to ensure the safe and reliable procurement, storage, control and distribution of quality pharmaceuticals. -

Government Notice No

6 No. 28552 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 3 MARCH 2006 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND CULTURE DEPARTEMENT VAN KUNS EN KULTUUR No. 185 3 March 2006 APPROVAL OF OFFICIAL GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES I, Z, Pallo Jordan, Minister of Arts and Culture officially approved the following geographical names on the advice of the South African Geographical Names Council on 1I November 2005. Dibaba (change of name from A settlement 10 km W of Carolina in Diepgezet) Mpumalanga Ekhandizwe (change of name from A settlement 65 km S of Globlersdal in Louis Creek) Mpumalanga eKulindeni A settlement 20 km S of Badplaas in Mpumalanga eMalahleni (change of name from A town (formerly Witbank) situated 30 Witban k) km E of Middleburg in Mpumalanga eMpuluzi A river 85 km W of Carolina in Mpumalanga eNdlulamithini (change of name from A settlement 6 km W of Standerton in Kaffirskraalkopie) Mpumalanga Engodlomezi (change of name from A mountain 86 km W of Carolina in SYd4 Mpumalanga eNtambende 1 (change of name from A settlement 9 W of Carolina in Devet) Mpumalanga eNtambende 11 (change of name from A settlement 9 W of Carolina in Nordeen) Mpumalanga STAATSKOERANT, 3 MAART 2006 No. 28552 7 eSilobela A township 1 km W of Carolina in Mpumafanga Etikhulungwane (change of name from A settlement 93 km SW of Carolina in Diepdale) Mpumalanga Etikwentsaba Estate A settlement 3 km W of Hazyview in Mpumalanga Ezimbuthumeni (change of name from A settlement 50 km E of Standerton in Kaffirskraal) Mpumalanga Ga-Morwe (change of name from A settlement f 7 km -

Albert Luthuli Local Municipality 2013/14

IDP REVIEW 2013/14 IIntegrated DDevelopment PPlan REVIEW - 2013/14 “The transparent, innovative and developmental local municipality that improves the quality of life of its people” Published by Chief Albert Luthuli Local Municipality Email: [email protected] Phone: (017) 843 4000 Website: www.albertluthuli.gov.za IDP REVIEW 2013/14 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms 6 A From the desk of the Executive Mayor 7 B From the desk of the Municipal Manager 9 PART 1- INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1.1 INTRODUCTION 11 1.2 STATUS OF THE IDP 11 1.2.1 IDP Process 1.2.1.1 IDP Process Plan 1.2.1.2 Strategic Planning Session 1.3 LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK 12 1.4 INTER GOVERNMENTAL PLANNING 13 1.4.1 List of Policies 14 1.4.2 Mechanisms for National planning cycle 15 1.4.3 Outcomes Based Approach to Delivery 16 1.4.4 Sectoral Strategic Direction 16 1.4.4.1 Policies and legislation relevant to CALM 17 1.4.5 Provincial Growth and Development Strategy 19 1.4.6 Municipal Development Programme 19 1.5 CONCLUSION 19 PART 2- SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 2.1 BASIC STATISTICS AND SERVICE BACKLOGS 21 2.2 REGIONAL CONTEXT 22 2.3 LOCALITY 22 2.3.1 List of wards within municipality with area names and coordinates 23 2.4 POPULATION TRENDS AND DISTRIBUTION 25 2.5 SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT 29 2.5.1 Land Use 29 2.5.2 Spatial Development Framework and Land Use Management System 29 Map: 4E: Settlement Distribution 31 Map 8: Spatial Development 32 2.5.3 Housing 33 2.5.3.1 Household Statistics 33 2.5.4 Type of dwelling per ward 34 2.5.5 Demographic Profile 34 2.6 EMPLOYMENT TRENDS 39 2.7 INSTITUTIONAL -

Table of Contents

GERT SIBANDE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY FINAL IDP 2011/12 TO 2013/14 A DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY STRIVING TO EXCEL IN GOOD GOVERNANCE AND QUALITY INFRASTRUCTURE Gert Sibande District Municipality i Foreword by the Executive Mayor It gives me great pleasure to present the Draft Integrated Development Plan for the 2011/12 to 2013/14 Financial Years, in the last year of this Current Term of Office. In reviewing our 2010/11 IDP and subsequently drafting our IDP and Budget respectively for 2011/12 to 2013/14 and beyond, we have consulted quite extensively with our communities in all our constituent Local Municipalities through their varying groupings using our IDP Representative Forum and other IGR structures institutionalised within our Municipality. Culminating from the state of the Nation and state of the Province Addresses respectively, and aforementioned consultation and engagements with varying stakeholders the following Key Development objectives were identified as pertinent in bringing about improved quality of life for our entire populace:- Facilitate creation of more jobs and descent work; Form strategic partnerships in fighting hunger and poverty; Advocate for access to quality education for all our citizens; Ensure proper health care for all our communities; Ensure sustainable development of all rural communities within our jurisdictional area; Harness the building of safer and secure communities To date resounding success has been realised in number of areas, where many of our people are living decent lives as a result of the services provided by the District in collaboration with its social partners. Whilst much has been achieved, there is still much that needs to be done to reverse and ultimately eradicate undesired consequences of underdevelopment, inequality, unemployment, HIV/AIDS and poverty. -

Mpumalanga Presentation

STATE OF THE PROVINCE: MPUMALANGA Briefing the Portfolio Committee on Home Affairs: 8 SEPTEMBER 2015 Presented by the Acting Provincial Manager: Ms ME Makatu TABLE OF CONTENT Provincial Overview 12 - 31 Capacity Information 32 - 38 Human Resources 39 - 49 Counter Corruption, Security Services and Labour Relations 50 -54 Finance and Budget 55 - 62 Operations 63 - 74 Ports of Entry 75 - 78 Challenges and Achievement 79 - 80 2 SOCIO-ECONOMIC REVIEW AND OUTLOOK OF MPUMALANGA - DECEMBER 2014 KEY FINDINGS • Mpumalanga’s percentage share of the national population of 54.0 million was 7.8 per cent, or 4.2 million, in 2014. • In total over the last year, Mpumalanga recorded 14 000 less jobs, however, the province registered an increase of 8 000 jobs in the third quarter of 2014. • Mpumalanga (29.3 per cent), recorded the fourth highest strict unemployment rate among the nine provinces. The expanded unemployment rate was 42.0 per cent in the third quarter of 2014. • The male unemployment rate was 25.7 per cent, the female unemployment was 33.6 per cent and the youth (15-34 years) unemployment rate was 41.8 per cent. • By 2013, 10.8 per cent of the people 20 years and older had not received any schooling. • In 2013, the Mpumalanga’s Grade 12 pass rate (77.6 per cent) was the fifth highest/lowest. • In 2012, the HIV prevalence rate of the female population aged 15–49 in Mpumalanga was 35.6 per cent – the second highest after KwaZulu-Natal. • In 2013, Mpumalanga recorded a HDI (The Human development index is a composite, relative index that attempts to quantify the extent of human development of a community. -

Limpopo Proposed Main Seat / Sub District Within the Proposed Magisterial District Tshitale Sub District of Makhado Magisterial

# # C! # # # # # ^ C! # .!C!# # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # C!^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ C! # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C!# # # C!C! # # # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # C!# # # # # # C! ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # C! # # # # # # # C! # #^ # # # # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # # # C! # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # C! # C! # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # C! # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # C!# # # ^ # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # # # ^ # # C! # C!# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #C! ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! C! # # # # # # # # C!# # # ##! # # # # C # C! # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # ^ # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # ## # # C! #C! # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # # C! ## # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # # # # ### # ! C! # # C # # # # C! # # ## ## C! # # C! .! # # # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # ## # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # C! # # # # ^ # # # # # # # C! # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # C! # # # # C!## # # # ## # C! # # # # C!# # # # # # # C! # C! # # # # # # ^ # # # C! # ^ # ! # ## C # # C! #C! ## # # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## # C! # # # # # # # # # # # # # #C! # # # # # # -

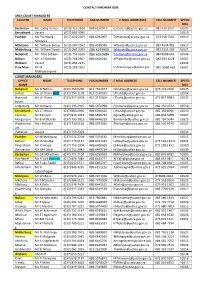

CONTACT INFORMATION AREA COURT MANAGERS CLUSTER NAME TELEPHONE FAX NUMBER E-MAIL ADDRESSES CELL NUMBER SPEED DIAL Barberton

CONTACT INFORMATION AREA COURT MANAGERS CLUSTER NAME TELEPHONE FAX NUMBER E-MAIL ADDRESSES CELL NUMBER SPEED DIAL Barberton Ms. Cathy Venter (013) 712 2104 086 6150972 [email protected] 082 334 2937 16503 Eerstehoek Vacant (017) 883 0090 16510 Evander Ms Thembela (017) 632 2204 086 6292907 [email protected] 073 158 7502 16512 Mcetywa Mdutjana Mr. William Baloyi (013) 947 2363 086 4018346 [email protected] 083 4304 485 16517 Middelburg Mr. William Nyathi (013) 262 2033 086 6293960 [email protected] 083 5355 283 16521 Nelspruit Mr. Titus Letlape (013) 753 6200 086 6292684 [email protected] 084 8388 663 16504 Nsikazi Mr. A Thabethe (013) 793 0567 086 6446010 [email protected] 082 933 3228 16527 Witbank Vacant (013) 656 2221 16534 Prov Man Mr IR (013) 283 7501 [email protected] 082 9568 663 16551 Mohlamonyane COURT MANAGERS OFFICE NAME TELEPHONE FAX NUMBER E MAIL ADDRESS CELL NUMBER SPEED NAME DIAL Nelspruit Ms N Ndlovu (013) 753 6299 013 7554077 [email protected] 076 271 2920 16525 Belfast Ms LP Thaha (Act) (013) 253 1138 013 2530035 [email protected] 16504 Waterval Ms LP Thaha (013) 257 0004 013 2570004 [email protected] 072 833 8983 16533 Boven Lydenburg Mr Chiloane (013) 235 2325 086 5070998 [email protected] 082 256 4722 16518 Eerstehoek Ms LT Mtuta (017) 883 0090 086 6046420 [email protected] 082 359 8096 16510 Carolina Mr DA Gule (017) 843 1033 086 5699732 [email protected] 082 844 5008 16507 Morgenzon Mr B Mahlambi (017) 793 3013 086 6446329 [email protected] -

Paleoarchean Bedrock Lithologies Across the Makhonjwa Mountains Of

Geoscience Frontiers 9 (2018) 603e665 HOSTED BY Contents lists available at ScienceDirect China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Geoscience Frontiers journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gsf Research Paper Paleoarchean bedrock lithologies across the Makhonjwa Mountains of South Africa and Swaziland linked to geochemical, magnetic and tectonic data reveal early plate tectonic genes flanking subduction margins Maarten de Wit a,*, Harald Furnes b, Scott MacLennan a,c, Moctar Doucouré a,d, Blair Schoene c, Ute Weckmann e, Uma Martinez a,f, Sam Bowring g a AEON-ESSRI (Africa Earth Observatory Network-Earth Stewardship Science Research Institute), Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa b Department of Earth Science & Centre for Geobiology, University of Bergen, Norway c Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, Guyot Hall, Princeton, NJ, USA d Department of Geosciences, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa e Department Geophysics, GFZ - German Research Centre for Geosciences, Helmholtz Centre, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, Germany f GISCAPETOWN, Cape Town, South Africa g Earth, Atmosphere and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA article info abstract Article history: The Makhonjwa Mountains, traditionally referred to as the Barberton Greenstone Belt, retain an iconic Received 12 June 2017 Paleoarchean archive against which numerical models of early earth geodynamics can be tested. We Received in revised form present new geologic and structural maps, geochemical plots, geo- and thermo-chronology, and 2 October 2017 geophysical data from seven silicic, mafic to ultramafic complexes separated by major shear systems across Accepted 5 October 2017 the southern Makhonjwa Mountains. All reveal signs of modern oceanic back-arc crust and subduction- Available online 31 October 2017 related processes. -

Chief-Albert-Luthuli

Chief Albert Luthuli Municipality Integrated Development Plan 2020-2021 The transparent, innovative and developmental municipality that improves the quality of life of its people 6/4/2020 INDEX ACCRONYMS AND ABREVIATIONS ABET Adult Based Education and Training AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ASGISA Accelerated Shared Growth Initiative South Africa CBO’s Community Based Organizations CETA Construction Education and Training Authority CHBC Community Home Base Care CIP Comprehensive Infrastructure Plan CFO Chief Financial Officer CMIP Consolidated Municipal Infrastructure Programme CM Community Services DAC District Aids Council DBSA Development Bank of South Africa DALA Department of Agriculture and Land Administration DARDLA Department of Development and Land Administration DCOGTA Department of Corporative Government and Traditional Affairs DHS Department of Human Settlements DLA Department of Land Affairs DM District Municipality DME Department of Minerals and Energy DPWR&T Department of Public Works, Roads and Transport DRDLR Department of Rural Development and Land Reform ECA Environmental Conservation Act EPWP Expanded Public Works Programme EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIP Environmental Implementation Plan EPWP Expanded Public Works Programme EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIP Environmental Implementation Plan EPWP Expanded Public Works Programme FBS Free basic Services FBE Free Basic Electricity GIS Geographic Information System GSDM Gert Sibande District Municipality HoD Head of Department HDI Human Development -

Mpumalanga No Fee Schools 2017

MPUMALANGA NO FEE SCHOOLS 2017 NATIONAL NAME OF SCHOOL SCHOOL PHASE ADDRESS OF SCHOOL EDUCATION DISTRICT QUINTILE LEARNER EMIS 2017 NUMBERS NUMBER 2017 800035522 ACORN - OAKS COMPREHENSIVE HIGH SCHOOL Secondary BOHLABELA 1 476 800034879 ALFRED MATSHINE COMMERCIAL SCHOOL Secondary STAND 7B CASTEEL TRUST BUSHBUCKRIDGE BOHLABELA 1 673 800030445 AMADLELO ALUHLAZA SECONDARY SCHOOL Secondary PHILA MYENI AVENUE ETHANDAKUKHANYA PIET RETIEF GERT SIBANDE 1 1386 800005058 AMALUMGELO PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary DWARS IN DIE WEG MORGENZON GERT SIBANDE 1 9 800000158 AMANZAMAHLE PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary PO BOX 1822 ERMELO ERMELO GERT SIBANDE 1 66 800000166 AMANZI PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary VYGEBOOM DAM BADPLAAS BADPLAAS GERT SIBANDE 1 104 800035381 AMON NKOSI PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary STAND NO. 6099 EXTENTION 12 BARBERTON EHLANZENI 1 727 800000240 ANDISA PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary STAND NO 3050 MABUYENI SIYABUSWA NKANGALA 1 286 800034906 ANDOVER PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary OKKERNOOTBOOM TRUST ACORNHOEK ACORNHOEK BOHLABELA 1 259 800034851 APLOS CHILOANE PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary KAZITHA TRUST ARTHURSEAT ACORNHOEK BOHLABELA 1 325 VLAKVARKFONTEIN 800000307 ARBOR PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary ARBOR DELMAS NKANGALA 1 351 FARM 800034852 ARTHURSEAT PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary ARTHURSEAT I ACORNHOEK ACORNHOEK BOHLABELA 1 236 800000406 BAADJIESBULT PRIMARY SCHOOL Combined APPELDOORN FARM CAROLINA CAROLINA GERT SIBANDE 1 184 800035179 BABATI PRIMARY SCHOOL Primary JUSTICIA TRUST JUSTICIA TRUST XIMHUNGWE BOHLABELA 1 500 800034907 BABINATAU SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL Secondary DINGLEDALE "B" ACORNHOEK -

Mpumalanga Proposed Main Seat / Sub District Within the Proposed

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # ## # # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # #!C # # # # # !C # ^ # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # !C # # # # # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # !C # # ## # # # !C # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C# # #^ # ## # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # ##^ !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # #!C ## # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # !C # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # #!C # !C # !C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # ### #!C # # !C # ## ## # # # !C # ## !C # # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### #^ # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # ## # !C !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # !C# # # # # !C ## # !C # # ^ # ## # # # !C# ^ # # !C # # ## # # !C # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # ## # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # !C # # # # # # -

Tiyani Sub District of Malamulele Magisterial District

!C !C^ !.!C !C !C^ ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C TTiiyyaannii SSuubb DDiissttrriicctt ooff MMaallaammuulleellee MMaaggiisstteerriiaall DDiissttrriicctt ^ !C !C !C !C DOORNSPRUIT LT WATERBOOM LANGVERWACHT VYGEBOOMSPRUIT 41 179 DRIEFONTEIN 30 SCHUYNSHOOGTE 27 er 286 !C 33 Malamulele rivi ing ELIM WOLFEROODE 29 or BALLYMORE WATERVAL LEVUBU !C D SHIRLEY ^ 38 WELGEVONDEN VAALKOP NABOOMKOP Main Seat 42 SAPS ONGEDACHT ñ Waterval 36 49 50 VYGEBOOMSDRIFT Shirindi MELKHOUTKOPJES KRUISFONTEIN Mashau 52 SCHIEL STYLDRIFT !C 53 314 WATERVAL 48 54 46 GROOTFONTEIN WATERVAL SAPS 47 45 Masia Vuwani MAMPAKUIL Louis Nkhesane Nkhensani Shikari 313 BOSCHKOPJE DE HOOP MODDERVLEI !C VUWANI TSHIMBUPFE 315 68 ONVERWACHT OOG VAN Trichardt 44 Sinthumule Mabodi Sub SAPS DOORNRIVIER Hlanganani 66 NIEUW MADOBI Davhana 318 ñ 230 Main Seat ENGELAND 81 District MAKHADO VLEYFONTEIN MASCHAPPE !C MALMESBURY 60 NIEUWVLAKTE MIDDELFONTEIN SAPS 310 82 ZEEKOEGAT 72 58 78 THORNDALE !C 79 LOCATIE VALDIGLEN 73 R578 !C !C ST VAN TABAAN 326 PIESANGFONTEIN Makhasa BUNGENI Ntshushi KHOMANANI MIDDELPLAATS 55 ROSSBACH BUSHY Hlanganani 658 HOOGMOED !C NK!CURI ZWARTFONTEIN UITSCHOT Klein-Letab Ka-Majosi NIEUWVELD 59 83 PARK a 69 BANKOP DIEPGEZET 392 84 GROENVALLEI PIESANGFONTEIN MARSEILLE 61 76 !C 319 89 Sub 71 WAGENDRIFT 390 SYFERFONTEIN !C 65 !C BELLEVUE