Making War on Terrorists— Reflections on Harming the Innocent*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Live News: a Survival Guide for Journalists

AA SURVIVALSURVIVAL GUIDEGUIDE FORFOR JOURNALISTSJOURNALISTS LIVELIVE NEWSNEWS Front cover picture: A press photographer in a cloud of teargas during a riot in Lima, Peru, in May 2000. Photo: AP / Martin Mejia Title page picture (right) A newspaper vendor waits for customers in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, one of many countries where media have been put under threat. In November 2002, an emergency aid programme was launched by the IFJ, the Communication Assistance Foundation, International Media Support and Media Assistance International, working with the Union Nationale des Journalistes de Côte d'Ivoire (UNJCI) and the West Africa Journalists Association. The programme included training on safety and conflict reporting. Photo: AP / Clement Ntaye. LIVE NEWS A SURVIVAL GUIDE FOR JOURNALISTS Written and produced for the IFJ by Peter McIntyre Published by the International Federation of Journalists, Brussels March 2003 With the support of the European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights. (i) Live News — A survival guide for journalists Published by the International Federation of Journalists March 2003. © International Federation of Journalists International Press Centre Residence Palace Rue de la Loi 155 B-1040 Brussels, Belgium ✆ +32 2 235 2200 http://www.ifj.org Editor in Chief Aidan White, General Secretary, IFJ Managing Editor Sarah de Jong, Human Rights Officer, IFJ [email protected] Projects Director Oliver Money-Kyrle Written and designed by Peter McIntyre, Oxford, UK [email protected] Acknowledgments The IFJ would like to thank: Associated Press Photos and Reuters, who donated the use of photos; AKE Ltd, Hereford, UK, for advice, information, facilities, and support; Mark Brayne (Dart Centre Europe) for advice on post trauma stress; Rodney Pinder, for comments on the drafts; All the journalists who contributed to, or were interviewed for, this book. -

Where Is Al-Qaida Going? by Anne Stenersen

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 11, Issue 6 Articles Thirty Years after its Foundation – Where is al-Qaida Going? by Anne Stenersen Abstract This article presents a framework for understanding al-Qaida, based on a new reading of its thirty-year history. Al-Qaida today is commonly labelled a ‘global insurgency’ or ‘global franchise.’ However, these labels are not sufficient if we want to understand what kind of threat al-Qaida poses to the West. Al-Qaida is better described as a revolutionary vanguard, engaged in a perpetual struggle to further its Salafi-jihadi ideology. Its strategy is flexible and opportunistic, and the organization uses a range of tools associated with both state and non-state actors. In the future al-Qaida is likely to treat international terrorist planning, and support to local insurgencies in the Muslim world, as two separate activities. International terrorism is currently not a prioritised strategy of al-Qaida, but it is likely to be so in the future, given that it manages to re-build its external operations capability. Keywords: Al-Qaida, terrorism, insurgency, strategy, external operations Introduction The status and strength of al-Qaida (AQ) are the subject of an ongoing debate. [1] There are two opposite and irreconcilable views in this debate: The first is that al-Qaida is strong and cannot be discounted. The other is that al-Qaida is in decline. [2] Those who suggest al-Qaida is strong, tend to emphasise the size and number of al-Qaida’s affiliates, especially in Syria, Yemen and Somalia; they also point to the rise of new leaders, in particular bin Laden’s son Hamza. -

Islamic State in Afghanistan: Challenges for Pakistan

Islamic State in Afghanistan: Challenges for Pakistan Islamic State in Afghanistan: Challenges for Pakistan Asad Ullah Khan & Arhama Siddiqua Abstract The Islamic State (IS) Wilayat-e-Khorasan, expanded at an alarmingly fast rate. However, because of losses, at the hands of both the Taliban and U.S.-backed Afghan forces, Islamic State’s future in Afghanistan was somewhat jeopardized. Nonetheless, seeing as the IS claimed responsibility for two deadly attacks on the Christian community in Pakistan’s south-western province of Balochistan among other such incidents it is no wonder that Pakistani counterterrorism officials are concerned about the spill-over of this faction of IS into their country. The recent efforts by Pakistan to safeguard its borders in the form of military operation and fencing have shaped a scenario in which the threat level for Pakistan is now on minimum level. The threat for Pakistan is more ideological in nature and needs to be defended with credible de- radicalization programs. It is pertinent to note here that Daesh is at the back foot and is adopting the tactics of negotiation instead of violence. Using qualitative data, this paper aims at analyzing Daesh as a potential threat for Pakistan, after considering the internal efforts done by Asad Ullah Khan and Arhama Siddiqua are Research Fellows at Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad, Islamabad. 103 JSSA, Vol. IV, No. 2 Asad Ullah Khan & Arhama Siddiqua Pakistan to counter this imminent threat; to what extent these efforts have secured Pakistan from this evil threat and what is still needed to be done. It will also aim to showcase that even though Pakistan must take the necessary measures, Daesh has not and will not be able to expand in Pakistani territory. -

Bachabazi in Afghanistan

AIHRC Causes and Consequences Of Bachabazi in Afghanistan (National Inquiry Report) 1393 AIHRC Report Identity Title: The Causes and Consequences of Bachabazi in Afghanistan (National Inquiry Report) Research: Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission Authors: Mohammad Hossein Saramad, Abdullah Abid, Mohammad Javad Alavi, Bismillah Waziri, Najibullah Babrakzai, and Latifa Sultani Revision and rewriting: Hussain Ali Moin Translators: AIHRC’s translation team (Ali Rahim Rahimi, Habibullah Habib, Murtaza Niazi) Data Extraction: Ahmed Shaheen Bashardost Design and layout: Mohammad Taqi Hasanzada Circulation: 1000 Volume Publisher: Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission Date of publication: Sunbual 1393 Address: Karte Se, Pooli Sorkh Road - Sixth District, Kabul, Afghanistan Contact numbers: +93(020)2500676 - 2500677 Email Address: [email protected] Website: www.aihrc.org.af Table of Contents Message of Dr. Sima Samar A Preface 1 Report Summary 3 Chapter One About the AIHRC and its Legal Mandates Concerning Children’s Rights 10 1.3 Legal Basis of the AIHRC’s Mandate in Conducting National Inquiries 13 Chapter Two Concept and Methodology of National Inquiry 15 2.1. What is National Inquiry? 15 2.2 Goals of a National Inquiry 17 2.3 Methodology of the National Inquiry 18 State Obligations towards Children’s Rights 20 Chapter three Legal Analysis of Bachabazi 23 3.1 What is Bachabazi 23 3.2 Bachabazi as a Crime and Human Rights Violation 24 3.3 Criminalization of Bachabazi 27 Chapter Four Analysis of the Statistical Findings 33 Demographic Particularities: 34 First- Demographic Particularities of the Perpetrators: 1. Age: 34 2. Literacy Level 35 3. Marital Status: 36 Second- Demographic Particularities of the Victims of Bachabazi: 1. -

The Bedlam Stacks Natasha Pulley

JULY 2017 The Bedlam Stacks Natasha Pulley An astonishing historical novel set in the shadowy, magical forests of South America, which draws on the captivating world of the international bestseller The Watchmaker of Filigree Street Description An astonishing historical novel set in the shadowy, magical forests of South America, which draws on the captivating world of the international bestseller The Watchmaker of Filigree StreetIt would have been a lovely thing to believe in, if I could have believed in anything at all.In 1860, Merrick Tremayne is recuperating at his family's crumbling Cornish estate as he struggles to recover from an injury procured on expedition in China. Dispirited by his inability to walk any futher than his father's old greenhouse, he is slowly coming round to his brother's suggestion that - after a life lived dangerously - he might want to consider a new path, into the clergy.But when the East India Trading Company coerces Merrick in to agreeing to go on one final expedition to the holy town of Bedlam, a Peruvian settlement his family knows well, he finds himself thrown into another treacherous mission for Her Majesty, seeking valuable quinine from a rare Cinchona tree. In Bedlam, nothing is as it seems. The Cinchona is located deep within a sacred forest where golden pollen furls in the air and mysterious statues built from ancient rock appear to move. Guided by the mysterious priest Raphael, who disappears for days on end into this shadowy realm, Merrick discovers a legacy left by his father and grandfather before him which will prove more valuable than the British Empire could ever have imagined. -

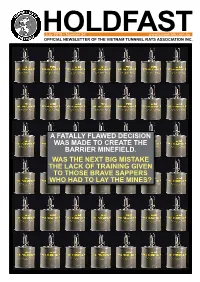

A Fatally Flawed Decision Was Made to Create the Barrier Minefield

HOLDFASTJuly 2019 - Number 34 www.tunnelrats.com.au OffICIal NEWslEttER of thE VIETNAM TUNNNEL Rats AssoCIatION INC. A FATALLY FLAWED DECISION WAS MADE TO CREATE THE BARRIER MINEFIELD. WAS THE NEXT BIG MISTAKE THE LACK OF TRAINING GIVEN TO THOSE BRAVE SAPPERS WHO HAD TO LAY THE MINES? NOSTALGIA PAGES 2 Optimum manning of a work team Nostalgia Pages Troop staff made sure Tunnel Rats were kept busy on menial tasks when back in base off operations, after all, who knows what a Tunnel Rat might get up to with time on his hands! The work party above is based on standard army procedure - if there are three men working you need three men watching over them. The ‘watchers’ were (L to R) Jock Meldrum, Yorkie Pages of great pics from the past to Schofield and Shorty Harrison. The fence mending is taking place at the amaze and amuse. Photo contribitions back of the 3 Troop lines in Nui Dat, some time in 1970/71. welcome. Send your favourite Vietnam pics (with descriptions, names and ap- Seriously weird sign at a prox dates) to Jim Marett 43 Heyington Vung Tau massage joint Place Toorak Vic 3142 or by email to: [email protected] HOLDFASTJuly 2019 - Number 34 www.tunnelrats.com.au OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE VIETNAM TUNNNEL RATS ASSOCIAT ION INC. A FATALLY FLAWED DECISION WAS MADE TO CREAT E THE BARRIER MINEFIELD. WAS THE NEXT BIG MISTAK E THE LACK OF TRAINING GIVEN TO THOSE BRAV E SAPPERS WHO HAD TO LAY THE MINES? Holdfast Magazine Written and edited by Jim Marett and published quarterly by the Vietnam Tunnel Rats Association 43 Heyington Place With its half man half woman illustration was this massage house way ahead Toorak Vic 3142 of its time in 1960’s Vung Tau? Were these trendsetters trying to appeal to Tel: 03-9824 4967 trans-gender folk even before we’d heard of such a thing? Or perhaps the Mobile: 0403 041 962 male soldier’s uniform and the female nurse’s uniform simply meant they [email protected] were wanting to attract business from soldiers on leave plus the nurses in www.tunnelrats.com.au the US and Australian military hospitals in Vung Tau. -

Only Afghanistan's Constitution to Decide on the Future Administration

Page 2 | NATIONAL Two Decades in Afghanistan: Was it Worth it? Page 3 | ECONOMY The Last Special It was 6am on September 12, 2001, when my phone rang and Gerry APTTA Trade Pact Forces Fighting the Brownlee said “turn on the TV, the U.S. is under attack”... Extended for Three Forever War Months Page 2 | NATIONAL Kabul Herat Nangarhar Balkh 14 / 3 17/ 4 23 / 12 16 / 9 Your Gateway to Afghanistan & the Region Sunday, March 7, 2021 Issue No. 931 www.heartofasia.af 10 afs Ghani: Only Afghanistan’s Constitution to Decide on the Future Administration decades’ achievements. Afghan-Iran Online He added: “By sacrificing, I mean Conference on Trade that all personal and group interests should be put aside, and people’s to be Held on Monday interests should be prioritized and An online conference is planned to be peace should be seen as a sacred held on opportunities and strategies goal.” for trade between Afghanistan and Iran Ghani reiterated that no one could on Monday, the portal of Iran Chamber decide on dissolving Afghanistan’s of Commerce, Industries, Mines and institutions that are approved in the Agriculture (ICCIMA) published. constitution. As per Tehran Times report, the online Calling the current opportunity for event will be attended by Hossein Salimi, peace unprecedented and unique, the chairman of Iran-Afghanistan Joint Ghani said Afghans want an end to the Chamber of Commerce. war that has continued for 42 years In this conference, the security and and that they want peace, but not the political situation of Afghanistan and peace of the graveyard. -

War Crimes Allegations and the UK: Towards a Fairer Investigative Process

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/129272 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications War Crimes Allegations and the UK: Towards a Fairer Investigative Process Andrew Williams1 University of Warwick War crimes allegations have dogged the UK military for decades. Yet there is no settled process to deal with them. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2019

INSIDE: l Canada set to recognize Tatar deportation as genocide – page 7 l Review: At The Ukrainian Museum’s film festival – page 9 l Ribbon-cutting highlights renovations at Bobriwka – page 17 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association, Inc., celebrating W its 125th anniversaryEEKLY Vol. LXXXVII No. 26-27 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JUNE 30 -JULY 7, 2019 $2.00 Ukrainian delegation bolts, Ukrainian Day advocacy event held in Washington Zelenskyy ‘disappointed’ as PACE reinstates Russia RFE/RL’s Ukrainian Service Ukraine’s delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has walked out in pro- test and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has voiced his “disappointment” over Russia having its voting rights reinstalled at the body after a three-year hiatus. In a June 25 statement on his Facebook page, President Zelenskyy said he tried to convince French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in separate meetings to not allow Russia back into Europe’s main human rights body until it meets PACE’s demands on adherence to princi- ples of rule of law and human rights. Ukrainian Day participants at the breakfast briefing session. “It’s a pity that our European partners didn’t hear us and acted differently,” Mr. Zelenskyy said of the lop- and a former co-chair of the Congressional Ukrainian sided vote from the Council of Europe’s 47 member On the agenda: Russia sanctions, Caucus, delivered observations from the perspective of states, where only 62 of the 190 delegates present energy security, occupation of Crimea, Congress. “Members of Congress highly value and appreci- ate the efforts of their constituents to visit Washington, opposed a report that made it possible for Russia to continued U.S. -

NCTC Annex of the Country Reports on Terrorism 2008

Country Reports on Terrorism 2008 April 2009 ________________________________ United States Department of State Publication Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism Released April 2009 Page | 1 Country Reports on Terrorism 2008 is submitted in compliance with Title 22 of the United States Code, Section 2656f (the ―Act‖), which requires the Department of State to provide to Congress a full and complete annual report on terrorism for those countries and groups meeting the criteria of the Act. COUNTRY REPORTS ON TERRORISM 2008 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Strategic Assessment Chapter 2. Country Reports Africa Overview Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership The African Union Angola Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi Comoros Democratic Republic of the Congo Cote D‘Ivoire Djibouti Eritrea Ethiopia Ghana Kenya Liberia Madagascar Mali Mauritania Mauritius Namibia Nigeria Rwanda Senegal Somalia South Africa Tanzania Uganda Zambia Zimbabwe Page | 2 East Asia and Pacific Overview Australia Burma Cambodia China o Hong Kong o Macau Indonesia Japan Republic of Korea (South Korea) Democratic People‘s Republic of Korea (North Korea) Laos Malaysia Micronesia, Federated States of Mongolia New Zealand Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, or Vanaatu Philippines Singapore Taiwan Thailand Europe Overview Albania Armenia Austria Azerbaijan Belgium Bosnia and Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Estonia Finland France Georgia Germany Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy Kosovo Latvia Page | 3 Lithuania Macedonia Malta Moldova Montenegro -

One Huge US Jail'

http://www.guardian.co.uk/afghanistan/story/0,1284,1440836,00.html, 'One huge US jail' Afghanistan is the hub of a global network of detention centres, the frontline in America's 'war on terror', where arrest can be random and allegations of torture commonplace. Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark investigate on the ground and talk to former prisoners Saturday March 19, 2005 The Guardian Kabul was a grim, monastic place in the days of the Taliban; today it's a chaotic gathering point for every kind of prospector and carpetbagger. Foreign bidders vying for billions of dollars of telecoms, irrigation and construction contracts have sparked a property boom that has forced up rental prices in the Afghan capital to match those in London, Tokyo and Manhattan. Four years ago, the Ministry of Vice and Virtue in Kabul was a tool of the Taliban inquisition, a drab office building where heretics were locked up for such crimes as humming a popular love song. Now it's owned by an American entrepreneur who hopes its bitter associations won't scare away his new friends. Outside Kabul, Afghanistan is bleaker, its provinces more inaccessible and lawless, than it was under the Taliban. If anyone leaves town, they do so in convoys. Afghanistan is a place where it is easy for people to disappear and perilous for anyone to investigate their fate. Even a seasoned aid agency such as Médécins Sans Frontières was forced to quit after five staff members were murdered last June. Only the 17,000-strong US forces, with their all-terrain Humvees and Apache attack helicopters, have the run of the land, and they have used the haze of fear and uncertainty that has engulfed the country to advance a draconian phase in the war against terror. -

Incarnation Children's Center Coverage by Third Party Media

Reporting by New York Post, U.K. Guardian, A&U Magazine, Associated Press, Fox News and AHRP on the Incarnation Children's Center drug trials. SHOCKING EXPERIMENTS: AIDS TOTS USED AS ʻGUINEA PIGSʼ By Douglas Montero “I took the girls out of hell—and the city stole them back” http:// www.leftgatekeepers.com/articles/ AIDsTotsUsedAsGuineaPigsByDouglasMontero.htm February 28, 2004 Jacqueline Hoerger will never forget the raid of her Nyack home by foster-care social workers who snatched the two HIV-positive sisters she was trying to adopt. Her crime: She was accused of neglect by the girlsʼ doctor of because she refused to give them a potentially dangerous cocktail of high-powered AIDS medications that she felt made them sicker. Hoerger, a pediatric nurse who spent two years as the girlsʼ foster mother, got the children from Manhattanʼs Incarnation Childrenʼs Center, a foster home for HIV- infected kids, where she worked from 1989 to 1993. There, she watched an array of researchers experiment on HIV-infected children, some as young as 3 months. She did her job, and figured the doctors at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, which is affiliated with ICC, knew what they were doing. It wasnʼt until she was allowed to take the sisters, ages 6 and 4, home in late 1998 that she began questioning the doctors and suspected that they were conducting research. “They were given to me as total wrecks.,” Hoerger said, describing how the oldest was hyperactive and sickly and the youngest was lethargic, extremely overweight and could barely walk. She learned the drug cocktails were highly toxic and mostly untested in children after listening to a speech by Dr, Philip Incao, of Denver, who travels across the country questioning current HIV medical practices.