New Wave - by Paul Myers - the Australian - February 01, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31011927.Pdf

2009/10 Broome and The Kimberley Emma Gorge, El Questro Station The real star of Australia Star in the adventure of a lifetime in one of the world’s most amazing wilderness areas. An ancient landscape of rugged ranges and stunning gorges, pristine beaches and untouched reefs. First Edition Valid 1 April 2009 – 31 March 2010. Contents The Broome and Kimberley region of Western Australia is a land of extraordinary contrasts, where red earth country meets the turquoise waters HOLIDAY PACKAGES 10 of the Indian Ocean. Along the coast lie some of Australia’s most beautiful beaches, rugged islands SELF DRIVE HOLIDAYS 12 and coral atolls with an amazing variety of marine life. Venture inland to spectacular rock formations, ancient gorges, rock pools and plunging waterfalls. EXPLORING BROOME AND THE KIMBERLEY 14 Not to be missed are the iconic beehive domes of the Bungle Bungle Range in World Heritage Listed Purnululu National Park. Enjoy relaxing days on the BROOME AND SURROUNDS 17 22 kilometre stretch of white sand known as Cable Beach in Broome, or cruise the amazing Kimberley coastline and inland waterways for a look at a part of the Kimberley only a privileged few have seen. Encounter amazing KUNUNURRA 29 wildlife and 20,000 year old rock art or travel along one of the best four wheel driving routes in Australia, the Gibb River Road. KIMBERLEY STATIONS AND WILDERNESS CAMPS 34 Romance and adventure are around every corner in the magical Kimberley. DERBY, FITZROY CROSSING AND HALLS CREEK 37 You could not make a better choice than to select a Great Aussie Holidays Broome & The Kimberley holiday. -

Meeting Responsible Officer Item Resolution Progress Comment Date Actioned Completed Minute Number OCM 25/02/2020 Chief Executive Officer 12.2.3

COUNCIL ACTION ITEMS Meeting Responsible Officer Item Resolution Progress Comment Date Actioned Completed Minute Number OCM 25/02/2020 Chief Executive Officer 12.2.3. Annual General Meeting of Electors That Council: The Senior Governance Officer will commence this 26-Feb-20 In progress 25/02/2020 - 118165 12 December 2019 1. In line with the Local Government Amendment Act 2019 and associated guidelines, draft a Shire of Wyndham East Kimberley Code of Conduct for body of work once the regulations and guidelines from Council Members, Committee Members and Election Candidates; the Department of Local Government, Sport and 2. Authorise the CEO to draft a separate Code of Conduct for Employees in line with Section 5.51(a) of the Local Government Act 1995 and; Cultural Industries have been published. In the interim 3. Ensure the provisions of each Code of Conduct are consistent with the regulations, which provide for the protection of residents against all forms of the current Code of Conduct still applies. bullying and harassment. OCM 25/02/2020 Stuart Dyson, Director Infrastructure 12.2.3. Annual General Meeting of Electors That Council includes the drain reference LOT 715, 41812 (Ivanhoe) within the 5 year drainage management plan which is currently being finalised by Included within the Drainage Implementation Plan. 25-Feb-20 In progress 25/02/2020 - 118166 12 December 2019 officers. Further engagement to take place with the Water Corporation as part of the drain sits within the P1 drinking water catchment area. OCM 25/02/2020 Stuart Dyson, Director Infrastructure 12.2.3. Annual General Meeting of Electors That Council undertakes a review of gardening and slashing activities and whether or not it is cost effective to outsource them. -

Kimberley Wilderness Adventures Embark on a Truly Inspiring Adventure Across Australia’S Last Frontier with APT

Kimberley Wilderness Adventures Embark on a truly inspiring adventure across Australia’s last frontier with APT. See the famous beehive domes of the World Heritage-listed Bungle Bungle range in Purnululu National Park 84 GETTING YOU THERE FROM THE UK 99 Flights to Australia are excluded from the tour price in this section, giving you the flexibility to make your own arrangements or talk to us about the best flight options for you 99 Airport transfers within Australia 99 All sightseeing, entrance fees and permits LOOKED AFTER BY THE BEST 99 Expert services of a knowledgeable and experienced Driver-Guide 99 Additional local guides in select locations 99 Unique Indigenous guides when available MORE SPACE, MORE COMFORT 99 Maximum of 20 guests 99 Travel aboard custom-designed 4WD vehicles built specifically to explore the rugged terrain in comfort SIGNATURE EXPERIENCES 99 Unique or exclusive activities; carefully designed to provide a window into the history, culture, lifestyle, cuisine and beauty of the region EXCLUSIVE WILDERNESS LODGES 99 The leaders in luxury camp accommodation, APT has the largest network of wilderness lodges in the Kimberley 99 Strategically located to maximise your touring, all are exclusive to APT 99 Experience unrivalled access to the extraordinary geological features of Purnululu National Park from the Bungle Bungle Wilderness Lodge 99 Discover the unforgettable sight of Mitchell Falls during your stay at Mitchell Falls Wilderness Lodge 99 Delight in the rugged surrounds of Bell Gorge Wilderness Lodge, conveniently located just off the iconic Gibb River Road 99 Enjoy exclusive access to sacred land and ancient Indigenous rock art in Kakadu National Park at Hawk Dreaming Wilderness Lodge KIMBERLEY WILDERNESS ADVENTURES EXQUISITE DINING 99 Most meals included, as detailed 99 A Welcome and Farewell Dinner 85 Kimberley Complete 15 Day Small Group 4WD Adventure See the beautiful landscapes of the Cockburn Range as the backdrop to the iconic Gibb River Road Day 1. -

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

About This Template

Your journey starts here Kimberley Complete Kimberley Complete by APT $9,195pp for 15 Days – Multiple departure dates PACKAGE INCLUDES A TASTE OF THE TOUR • Experiences in 19 destinations Venture into an unexplored rugged land. • Expert APT Driver-Guide The Kimberleys are mesmerizing. The • Locally inspired dining - a total of 41 colours and formations of this great land meals will leave you spell bound. With APT, you • APT's Exclusive Network of Wilderness Lodges will learn about this land from their • Custom designed 4WD dedicated guides, from the Bungle Bungles • Maximum 22 guests to Mitchell Falls. *Conditions apply. Prices are for twin share. Advertised prices are correct at time of publication and are subject to availability and change at any time without notification due to fluctuations in charges, taxes and currency. Additional charges and seasonal surcharges may apply Other conditions apply. To find out more call Anthony Lee your personal travel manager 0432 685 108 [email protected] facebook.com/anthonyleetravel travelmanagers.com.au/anthonylee Part of the House of Travel Group ACN: 113 085 626 Member: IATA, AFTA, CLIA Kimberley Complete by APT Your Small Group Journey itinerary Day 1: Arrive Broome: Arrive in Halls Creek, before arriving at Day 6: Lake Argyle, Ord River, Broome, where we meet you on arrival Purnululu National Park. Settle in to Kununurra: Travel to Lake Argyle and and transfer you to your hotel, your lodge before an open-air dinner join a wildlife cruise on the mighty Ord Broome's iconic Cable Beach Club tonight. River. From a modern shaded vessel, Resort and Spa. -

LA QON 4115 (A)-(C) 1 (A) (B) (C)(I) WA Health Is Unable to Provide Data for 2015 -2016. As This Period Is Prior to the Establis

LA QON 4115 (a)-(c) (a) (i) 2015/16 (ii) 2016/17 (iii) 2017/18 Department of Health Not applicable $7,275.86 $1,697.70 Health Support Services Not applicable Nil Nil Child and Adolescent Health Service Not applicable Nil $771,498.75 East Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable $4,380,602 $9,433,011 North Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable $349,332 $6,376,144 South Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable $1,260,000 $16,296,000 WA Country Health Service Nil $958,501 $6,303,319 Metropolitan Health Services (Debts in $3,215,000 2015/16 were written off by the Metropolitan Health Services Board, as this was prior to the establishment of Health Service Providers as separate statutory authorities. (b) (i) 2015/16 (ii) 2016/17 (iii) 2017/18 Department of Health Not applicable 36 12 Health Support Services Not applicable Nil Nil Child and Adolescent Health Service Not applicable Nil 1,934 East Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable 12,223 11,206 North Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable 7,918 16,254 South Metropolitan Health Service Not applicable 2,845 16,603 WA Country Health Service Nil 2,463 9,906 Metropolitan Health Services (Debts in 20,063 2015/16 were written off by the Metropolitan Health Services Board, as this was prior to the establishment of Health Service Providers as separate statutory authorities). (c)(i) WA Health is unable to provide data for 2015 -2016. As this period is prior to the establishment of Health Service Providers as separate statutory authorities, gathering this information would be extremely labour intensive and time consuming. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ‘Ilma’ - Ashley Hunter - ‘Ilma’

THE KIMBERLEY LAND COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2012 ‘Ilma’ - Ashley Hunter - ‘Ilma’ Kimberley Land Council Annual Report 2012 I 1 2 I Kimberley Land Council Annual Report 2012 Contents Introduction & Overview 4 Our Mission, Vision & Values 5 Co-chair Report 6 Board of Directors 7 CEO Report 8 Our Orgaisation 10 Kimberley Land Council 12 Role and Functions 13 Organisational Structure 14 Executive Roles & Responsibilities 15 Corporate Governance 16 Human Resources 19 Performance Report 20 Native Title Climate 22 Native Title Claim Updates 24 Looking After Country 36 Land & Sea Management 38 Projects 39 Kimberley Ranger Program & 43 Indigenous Protected Areas Glossary 53 Financial Statements 54 “I feel proud of the Kimberley Land Council, cause it’s there talking for our mob. We’ve got to back one another. We’ve got to be strong and stand up for our people. We’ve got to sit together and we’ve got to work together. Together, we are the Traditional Owners of this country.’’ Joe Brown, KLC Special Adviser Kimberley Land Council Annual Report 2012 I 3 Introduction & overview The Kimberley Land Council was established in 1978 following a dispute between Kimberley Aboriginal people, The Western Australian Government and an International mining company at Noonkanbah. The KLC was set up by Kimberley Aboriginal people as a peak regional community organisation, to secure the rights and interests of Kimberley Traditional Owners in relation to their land and waters and to protect their significant places. The KLC has experienced rapid growth in recent years. While fulfilling our role as a Native Title Representative Body remains the core business of our organisation, we have expanded to include a broad range of programs and activities that help us to achieve the vision of our members. -

Threatened and Priority Flora List 5 December 2018.Xlsx

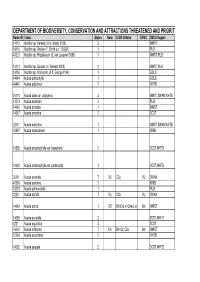

DEPARTMENT OF BIODIVERSITY, CONSERVATION AND ATTRACTIONS THREATENED AND PRIORITY Name ID Taxon Status Rank IUCN Criteria EPBC DBCA Region 14112 Abutilon sp. Hamelin (A.M. Ashby 2196) 2 MWST 14110 Abutilon sp. Onslow (F. Smith s.n. 10/9/61) 1 PILB 43021 Abutilon sp. Pritzelianum (S. van Leeuwen 5095) 1 MWST,PILB 14114 Abutilon sp. Quobba (H. Demarz 3858) 2 MWST,PILB 14155 Abutilon sp. Warburton (A.S. George 8164) 1 GOLD 14044 Acacia adinophylla 1 GOLD 44442 Acacia adjutrices 3 WHTB 16110 Acacia alata var. platyptera 4 MWST,SWAN,WHTB 13074 Acacia alexandri 3 PILB 14046 Acacia ampliata 1 MWST 14047 Acacia amyctica 2 SCST 3210 Acacia anarthros 3 MWST,SWAN,WHTB 43557 Acacia anastomosa 1 KIMB 14585 Acacia ancistrophylla var. lissophylla 2 SCST,WHTB 14048 Acacia ancistrophylla var. perarcuata 3 SCST,WHTB 3219 Acacia anomala TVUC2a VU SWAN 43580 Acacia anserina 2 KIMB 13073 Acacia aphanoclada 1 PILB 3220 Acacia aphylla TVUC2a VU SWAN 14049 Acacia aprica TCRB1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v) EN MWST 14050 Acacia arcuatilis 2 SCST,WHTB 3221 Acacia argutifolia 4 SCST 14051 Acacia aristulata TENB1+2c; C2a EN MWST 12248 Acacia ascendens 2 WHTB 14052 Acacia asepala 2 SCST,WHTB 14725 Acacia ataxiphylla subsp. ataxiphylla 3 SCST,WHTB B1ab(iii,iv,v)+2ab(iii 14687 Acacia ataxiphylla subsp. magna TEN,iv,v); C2a(i); D EN WHTB 19507 Acacia atopa 3 MWST 14053 Acacia auratiflora TVUC2a(i) EN WHTB 3230 Acacia auricoma 3 GOLD 14054 Acacia auripila 2 PILB 12249 Acacia awestoniana TCRC2a(ii) VU SCST 31784 Acacia barrettiorum 2 KIMB 41461 Acacia bartlei 3 SCST 3237 Acacia benthamii 2 SWAN 44472 Acacia besleyi 1 SCST 14611 Acacia bifaria 3 SCST 3243 Acacia botrydion 4 WHTB 13509 Acacia brachyphylla var. -

Oceanmagazine#57

Reviews MONDANGO 3 room wiTh MAJESTY 135 BLUSH COMO ACOMO, A TRIUMPHview OF DUBOIS DESIGN AND FEADSHIP QUALITY NORTh WEST WILDeRNESS awe AND WONDER OF AUSTRALIA’S KIMBERLEY GLiTZ AND GLAMOuR A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO THE MONACO YACHT SHOW 0 2110 2 5 OCeAN LiFe OCeAN DesiGN AusTRALiAN MADe sTAYiNG sAFe WONDERFUL WORLD (inc.gst) THREE GREAT YACHTING NO PLACE LIKE HOME HIGH-TECH SECURITY OF WHISKEY MINDS JOIN FORCES – A BEACON OF QUALITY SYSTEMS AT SEA 77183 $12.95 PP:255003/07458 issue 57 9 128 destination t’s no coincidence that tourism Christian Flet australia chose Western australia’s ivast Kimberley region to showcase the grandeur and spectacle of our magnificent landscapes in the 2008 blockbuster Australia. Unlike the Central C her australian pair, Uluru and Kata tjuta, where tourism has been active for over half a century, visitors to the Kimberley have only been arriving in appreciable numbers for barely half that period. Perhaps as a result of near-impossible isolation, harsh climates and the almost complete lack of infrastructure, australia’s north West remained off the tourism radar until adventure cruisers and remote fishing charter operators changed that. the gobsmacking panoramas of Mitchell Falls, raft Point and mystical Montgomery reef could not have been better suited to the big-budget cinematography of Baz luhrmann’s movie. love it or not, the golden-hued ancient landscapes of the Kimberley were presented spectacularly on screen. More recently, however, it’s been the furore over oil and gas exploration highlighting the region, with local tourism businesses fearful that unfettered development will tarnish the unspoilt quality of the iconic Kimberley. -

LOCALITY BAILIFF KM AMOUNT STANDARD GST PAYABLE Rate Per Kilometre 1.1 ABBA RIVER Busselton 10 11.00 ABBEY Busselton 10 11.00 AB

LOCALITY BAILIFF KM AMOUNT STANDARD GST PAYABLE Rate Per Kilometre 1.1 ABBA RIVER Busselton 10 11.00 ABBEY Busselton 10 11.00 ABYDOS South Hedland 129 141.90 ACTON PARK Busselton 13 14.30 ADELINE Kalgoorlie 4 4.40 4.85 AGNEW Leinster 20 22.00 AJANA Northampton 45 49.50 ALANOOKA Geraldton 56 61.60 67.75 Albany Albany 2 2.20 ALBION DOWNS Wiluna 86 94.60 ALDERSYDE Brookton 29 31.90 ALCOA (CARCOOLA) Pinjarra 5 5.50 ALICE DOWN STATION Halls Creek 25 27.50 ALLANSON Collie 4 4.40 ALEXANDER BRIDGE Margaret River 12 13.20 AMELUP Gnowangerup 40 44.00 AMERY Dowerin 8 8.80 AMBERGATE Busselton 10 11.00 ANKETEL STATION Mt. Magnet 120 132.00 ARDATH Bruce Rock 25 27.50 ARGYLE " NOT LAKE ARGYLE" Argyle 2 2.20 ARMSTRONG HILLS Mandurah 36 39.60 ARRINO (WEST) Three Springs 44 48.40 ARTHUR RIVER Wagin 29 31.90 ARTHUR RIVER STATION Gascoyne Junction 134 147.40 AUSTIN Cue 29 31.90 AUSTRALIND Bunbury 14 15.40 16.95 AUGUSTA Augusta 2 2.20 AVALON Mandurah 9 9.90 BAANDEE Kellerberrin 26 28.60 BABAKIN Merredin 71 78.10 BADDERA Northampton 10 11.00 BADGEBUP Katanning 36 39.60 BADGIN York 30 33.00 BADGINGARRA POOL Moora 56 61.60 BADJA (PASTORAL STATION) Yalgoo 29 31.90 BAKER’S HILL Wundowie 13 14.30 BALBARUP Manjimup 8 8.80 BALFOUR DOWNS STATION Nullagine 240 264.00 BALICUP Cranbrook 28 30.80 BALKULING York 43 47.30 BALLADONG York 2 2.20 BALLADONIA Norseman 218 239.80 BALLAGUNDI Kalgoorlie 29 31.90 35.10 BALLIDU Wongan Hills 32 35.20 BALINGUP Donnybrook 30 33.00 BALLY BALLY Beverley 24 26.40 BANDYA Laverton 131 144.10 BANJAWARN STATION Laverton 168 184.80 BAMBOO SPRINGS -

Aboriginal Management and Planning for Country: Respecting and Sharing Traditional Knowledge

Land & Water Australia wish to advise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders that the following publication may contain images of deceased persons. Land & Water Australia and the author apologises for any distress this might cause. Aboriginal Management and Planning for Country: respecting and sharing traditional knowledge Full report on Subprogram 5 of the Ord-Bonaparte program Kylie Pursche Kimberley Land Council ‘…country he bin cry for us. It change when we leave…’ ‘…I never went to school but my brain working for my country…’ Aboriginal Management and Planning for Country: respecting and sharing traditional knowledge Full report on Subprogram 5 of the Ord–Bonaparte Program Kylie Pursche Kimberley Land Council This project was funded by: Land & Water Australia Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation Australian Institute of Marine Science Australian National University Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Savannas Management Department of Agriculture, Western Australia Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australia Kimberley Land Council Shire of Wyndham–East Kimberley Water and Rivers Commission, Western Australia. Published by: Land & Water Australia GPO Box 2182 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: (02) 6263 6000 Facsimile: (02) 6263 6099 Email: [email protected] WebSite: www.lwa.gov.au © Land & Water Australia Disclaimer: The information contained in this publication is intended for general use, to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the sustainable management of land, water and vegetation. The information should not be relied upon for the purpose of a particular matter. Legal advice should be obtained before any action or decision is taken on the basis of any material in this document. -

Durack River and Karunjie Stations Western Australia 26 May–5 June 2014 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program

Durack River and Karunjie Stations Western Australia 26 May–5 June 2014 Bush Blitz species discovery program Durack River and Karunjie Stations 26 May–5 June 2014 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study DPaW Department of Parks and Wildlife EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) FRM Act Fish Resources Management Act 1994 (Western Australia) ILC Indigenous Land Corporation KLC Kimberley Land Council MAGNT Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory UNSW University of New South Wales WAM Western Australian Museum WAH Western Australian Herbarium WC Act Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 (Western Australia) Page 2 of 36 Durack River and Karunjie Stations 26 May–5 June 2014 Summary Durack River and Karunjie Stations in the Kimberley, Western Australia, were the focus of a Bush Blitz expedition from 26 May to 5 June 2014. These former pastoral properties are located along the Gibb River Road within the Pentecost River Catchment. The Indigenous Land Corporation (ILC) purchased the properties along with the neighbouring Home Valley Station and opened a pastoral, tourism and indigenous training centre in 2008. The Kimberley is one of the most ecologically important regions of Australia. Collecting occurred within a relatively dry corridor running north to south through the eastern Kimberley, which is less well known than the wetter parts of the western Kimberley or the area between Kununurra and the Northern Territory border.