Degruyter Opar Opar-2020-0130 98..117 ++

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

A CLASS ACADEMY OF ENGLISH BELS GOZO EUROPEAN SCHOOL OF ENGLISH (ESE) INLINGUA SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES St. Catherine’s High School, Triq ta’ Doti, ESE Building, 60, Tigne Towers, Tigne Street, 11, Suffolk Road, Kercem, KCM 1721 Paceville Avenue, Sliema, SLM 3172 Mission Statement Pembroke, PBK 1901 Gozo St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Tel: (+356) 2010 2000 Tel: (+356) 2137 4588 Tel: (+356) 2156 4333 Tel: (+356) 2137 3789 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT profession and sector. Malta Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inlinguamalta.com can boast that both its ELT profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being Web: www.aclassenglish.com Web: www.belsmalta.com Web: www.ese-edu.com practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. All this has resulted in rapid growth for INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH the sector. ACE ENGLISH MALTA BELS MALTA EXECUTIVE TRAINING LANGUAGE STUDIES Bay Street Complex, 550 West, St. Paul’s Street, INSTITUTE (ETI MALTA) Mattew Pulis Street, Level 4, St.George’s Bay, St. Paul’s Bay ESE Building, Sliema, SLM 3052 ELT Schools St. Julian’s, STJ 3311 Tel: (+356) 2755 5561 Paceville Avenue, Tel: (+356) 2132 0381 There are currently 37 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Malta can boast that both its ELT Tel: (+356) 2713 5135 Email: [email protected] St. Julian’s, STJ 3103 Email: [email protected] profession and sector are well structured and closely monitored, being the first and practically only Email: [email protected] Web: www.belsmalta.com Tel: (+356) 2379 6321 Web: www.ielsmalta.com language-learning destination in the world with legislation that assures that every licensed school Web: www.aceenglishmalta.com Email: [email protected] maintains a national quality standard. -

Gozo During the Second World War - a Glimpse

Gozo During the Second World War - a Glimpse CHARLES BEZZINA Introduction squad was not set up in Gozo during the war and British soldiers, who started to visit Gozo in March The part played by Gozo during the war was 1941, were only stationed in Gozo primary schools somewhat different from that of Malta. Gozo, or other private buildings just for short periods, though subject to the same rules and regulations of to relax and also for their military exercises and wartime Malta, was not a military objective and it parades to boost the local morale. It was only in was only in early 1942 that Gozo became an enemy mid-1943 that, because of the temporary Gozo target. Yet Gozitans feared the enemy especially Airfield, some defence precautions were taken to in 1942 since the island was defenceless and had guard against any air attacks. nothing to fight with. Therefore certain exigencies that were introduced in Malta from the outbreak of From the outbreak of the war with Italy in June 1940 the hostilities with Italy, became in force in Gozo up to mid-December 1941, Italian and German only after the Luftwaffe intensified the attacks on the planes just passed over Gozo and occasionally island in 1942. Thus in Gozo public shelter digging dropped bombs only to lighten their load and turn and construction did not start before March 1941, back as fast as they could. Thus Gozo as a small the Demolition and Clearance was not established and defenceless island never endured the harsh until February 1942 and the Home Guard only came bombing that took place incessantly on Malta. -

Temporary Closing of Places of Interest

COVID-19 TEMPORARY CLOSING OF PLACES OF INTEREST In view of the current situation regarding COVID-19, a number of places of interest, museums, heritage sites and attractions have announced that they will be temporarily closed. Some have closed for a definite period of time, whilst others have closed until further notice. This measure is being taken as a precaution to safeguard the wellbeing of staff and visitors, It is advisable to check the respective website before visiting. Places of Interest that have announced temporary closing include the following: All FONDAZJONI WIRT ARTNA sites, namely: Saluting Battery - Valletta Lascaris War Rooms - Valletta War HQ Tunnels - Valletta Unfinished WW2 Bunker - Valletta Fort Rinella - Kalkara Malta at War Museum - Vittoriosa Bieb is-Sultan - Vittoriosa All HERITAGE MALTA museums and sites, namely: The Palace Armoury - Valletta Palace State Rooms - Valletta Fort St Elmo/National War Museum - Valletta National Museum of Archaeology - Valletta MUZA - Valletta Skorba - Mgarr Ta' Ħaġrat - Mgarr Ta' Bistra Catacombs - Mosta St Paul’s Catacombs - Rabat Domus Romana - Rabat National Museum of Natural History - Mdina Fort St Angelo - Vittoriosa Inquisitors Palace - Vittoriosa Malta Maritime Museum - Vittoriosa Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum – Paola Tarxien Temples - Tarxien Ħaġar Qim Temples - Qrendi Mnajdra Temples - Qrendi Għar Dalam - Birżebbuġa Borġ in-Nadur Temples – Birżebbuġa Old Prisons, Citadel – Victoria, Gozo Citadel Visitor Centre - Victoria, Gozo Gran Castello Historic -

Malta & Gozo Directions

DIRECTIONS Malta & Gozo Up-to-date DIRECTIONS Inspired IDEAS User-friendly MAPS A ROUGH GUIDES SERIES Malta & Gozo DIRECTIONS WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Victor Paul Borg NEW YORK • LONDON • DELHI www.roughguides.com 2 Tips for reading this e-book Your e-book Reader has many options for viewing and navigating through an e-book. Explore the dropdown menus and toolbar at the top and the status bar at the bottom of the display window to familiarize yourself with these. The following guidelines are provided to assist users who are not familiar with PDF files. For a complete user guide, see the Help menu of your Reader. • You can read the pages in this e-book one at a time, or as two pages facing each other, as in a regular book. To select how you’d like to view the pages, click on the View menu on the top panel and choose the Single Page, Continuous, Facing or Continuous – Facing option. • You can scroll through the pages or use the arrows at the top or bottom of the display window to turn pages. You can also type a page number into the status bar at the bottom and be taken directly there. Or else use the arrows or the PageUp and PageDown keys on your keyboard. • You can view thumbnail images of all the pages by clicking on the Thumbnail tab on the left. Clicking on the thumbnail of a particular page will take you there. • You can use the Zoom In and Zoom Out tools (magnifying glass) to magnify or reduce the print size: click on the tool, then enclose what you want to magnify or reduce in a rectangle. -

Fortification Drawings of the Baroque Age at the National Library of Malta

European Journal of Science and Theology, December 2019, Vol.15, No.6, 197-202 BOOK REVIEW Lines of defence: fortification drawings of the Baroque Age at the National Library of Malta Denis De Lucca, Stephen Spiteri and Hermann Bonnici (eds.) International Institute for Baroque Studies, University of Malta, Malta, 2015, 399 pp, ISBN: 978-99957-856-1-1, EUR 850 In 2015, the International Institute for Baroque Studies in collaboration with Malta Libraries published its magnum opus ‘Lines of Defence: Fortification Drawings of the Baroque Age at the National Library of Malta’. This work is edited by three academics of the Institute, namely Denis De Lucca (Director), Stephen Spiteri (a leading scholar in the field of historical research focused on fortress building) and Hermann Bonnici (an architect whose specialisation is the conservation/restoration of Malta’s fortifications). Albeit the publication’s main forward was penned by Juanito Camilleri (Rector of the University of Malta at the time of publication), one also finds an informal one by Oliver Mamo (the National Librarian and CEO of Malta Libraries at the time of publication) followed by a general introduction to the collection of drawings housed at the National Library of Malta (NLM) by Maroma Camilleri (Senior Librarian at the NLM). This publication is an all-encompassing compendium of graphical designs relating to the diverse fortifications studded all over the Maltese Islands. It brings together a unique collection, mostly preserved at the NLM in Valletta, of plans and drawings of mainly eighteenth century military architecture in Malta and Gozo. This significant publication constitutes the largest collection of original plans, elevations and axonometric-type/perspective drawings of fortifications, projected and/or realised on the islands during the rule of the Hospitaller Order (1530-1798). -

From Jerusalem to Malta: the Hospital's Character and Evolution1 from Peregrinationes, a Publication of the Accademia Internazionale Melitense

From Jerusalem to Malta: the Hospital's character and evolution1 From Peregrinationes, a publication of the Accademia Internazionale Melitense Anthony Luttrell The origins of the Order of St. John remain somewhat obscure, and the homelands of the founder Girardus, perhaps an Italian, and of the first Master Fr. Raymond de Podio, possibly French or Provençal, are unknown. The emergence of the Hospital was an aspect of the profound religious revival in the West which generated a reformed papacy, monastic renewal based on Cluny, lay movements for the support of charity and hospitals, and the first crusade. Probably in about 1070 various merchants from Amalfi, and perhaps from elsewhere in Southern Italy, founded a hospice for Latin pilgrims in Jerusalem which was attached to the Benedictine house of Sancta Maria Latina; subsequently a second house was established for women. These hospices were for pilgrims and especially for the poor rather than for the medically sick. Their staff may have been lay brethren under some vow of obedience. The hospices seem not to have had their own incomes or endowments, their resources coming from the Amalfitans and the Benedictines and perhaps also from pilgrims and other visitors2. The crusaders' conquest of 1099 brought fundamental change to Jerusalem which became a Christian city. The number of Latin pilgrims and poor increased, the Holy Sepulchre was occupied by Latin canons and the Greek Patriarch was replaced by a Latin one. The Benedictines of Sancta Maria Latina lost their predominance in Jerusalem. The Latin hospice survived under its competent leader Girardus; it was detached from Sancta Maria Latina and was somehow associated with the Holy Sepulchre nearby. -

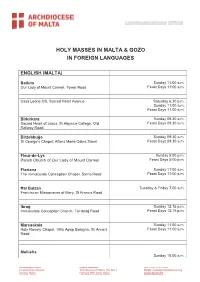

Holy Masses in Malta & Gozo in Foreign Languages

HOLY MASSES IN MALTA & GOZO IN FOREIGN LANGUAGES ENGLISH (MALTA) Balluta Sunday 11:00 a.m. Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Tower Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Casa Leone XIII, Sacred Heart Avenue Saturday 6:30 p.m. Sunday 11:00 a.m. Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Birkirkara Sunday 09:30 a.m. Sacred Heart of Jesus, St Aloysius College, Old Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Railway Road Birżebbuġa Sunday 09:30 a.m. St George’s Chapel, Alfons Maria Galea Street Feast Days 09:30 a.m. Fleur-de-Lys Sunday 5:00 p.m. Parish Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Feast Days 5:00 p.m. Floriana Sunday 11:00 a.m. The Immaculate Conception Chapel, Sarria Road Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Ħal Balzan Tuesday & Friday 7:00 a.m. Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, St Francis Road Ibraġ Sunday 12:15 p.m. Immaculate Conception Church, Tal-Ibraġ Road Feast Days 12:15 p.m. Marsaskala Sunday 11:00 a.m. Holy Rosary Chapel, Villa Apap Bologna, St Anne’s Feast Days 11:00 a.m. Road Mellieħa Sunday 10:00 a.m. Shrine of Our Lady, Pope’s Visit Square Feast Days 10:00 a.m. Msida Sunday 10:00 a.m. Dar Manwel Magri, Mgr Carmelo Zammit Street Naxxar Sunday 11:30 a.m. Church of Divine Mercy, San Pawl tat-Tarġa Feast Days 11:30 a.m. The Risen Christ Chapel, Hilltop Gardens Sunday 11:30 a.m. Retirement Village, Inkwina Road Paceville Sunday 11:30 a.m. -

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr

Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MALTA • SICILY • ITALY Led by Dr. Carl Rasmussen MAY 11-22, 2021 organized by Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome / May 11-22, 2021 Malta Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Martyrdom in Rome MAY 11-22, 2021 Fri 14 May Ferry to POZZALLO (SICILY) - SYRACUSE – Ferry to REGGIO CALABRIA Early check out, pick up our box breakfasts, meet the English-speaking assistant at our hotel and transfer to the port of Malta. 06:30am Take a ferry VR-100 from Malta to Pozzallo (Sicily) 08:15am Drive to Syracuse (where Paul stayed for three days, Acts 28.12). Meet our guide and visit the archeological park of Syracuse. Drive to Messina (approx. 165km) and take the ferry to Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland (= Rhegium; Acts 28:13, where Paul stopped). Meet our guide and visit the Museum of Magna Grecia. Check-in to our hotel in Reggio Calabria. Dr. Carl and Mary Rasmussen Dinner at our hotel and overnight. Greetings! Mary and I are excited to invite you to join our handcrafted adult “study” trip entitled Following Paul from Shipwreck on Malta to Sat 15 May PAESTUM - to POMPEII Martyrdom in Rome. We begin our tour on Malta where we will explore the Breakfast and checkout. Drive to Paestum (435km). Visit the archeological bays where the shipwreck of Paul may have occurred as well as the Island of area and the museum of Paestum. Paestum was a major ancient Greek city Malta. Mark Gatt, who discovered an anchor that may have been jettisoned on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). -

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and of Malta – a General History of the Order of Malta

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OAR@UM Emanuel Buttigieg THE SOVEREIGN MILITARY HOSPITALLER ORDER OF ST. JOHN OF JERUSALEM OF RHODES AND OF MALTA – A GENERAL HISTORY OF THE ORDER OF MALTA INTRODUCTION: HOSPITALLERS Following thirteen years of excavation by the Israel Antiquities Authority, a thousand-year-old structure – once a hospital in Jerusalem – will be open to the public; part of it seems earmarked to serve as a restaurant. 1 In Syria, as the civil war rages on, reports and footage have been emerging of explosions in and around Crac des Chevaliers castle, a UNESCO World Heritage site. 2 During the interwar period (1923–1943), the Italian colonial authorities in the Dodecanese engaged in a wide-ranging series of projects to restore – and in some instances redesign – several buildings on Rhodes, in an attempt to recreate the late medieval/Renaissance lore of the island. 3 Between 2008 and 2013, the European Regional Development Fund provided the financial support necessary for Malta to undertake a large-scale restoration of several kilometres of fortifications, with the aim of not only preserving these structures but also enhancing Malta’s economic and social well- -being.4 Since 1999, the Sainte Fleur Pavilion in the Antananarivo University Hospital Centre in Madagascar has been helping mothers to give birth safely and assisting infants through care and research. 5 What binds together these seemingly disparate, geographically-scattered buildings, all with their stories of hope and despair? All of them – a hospital in Jerusalem, a castle in Syria, structures on Rhodes, fortifications on Malta, and yet another hospital, this time in Madagascar – attest to the constant (but evolving) mission of the Order of Malta “to Serve the Poor and Defend the Faith” over several centuries. -

Nadur and Its Countryside Mario Saliba

Nadur and its Countryside MARIO SALIBA Introduction on the northeast of the island between the villages of Xagħra and Qala. It lies, on top of the first of Gozo still offers tourists an opportunity to enjoy a the three hills, synonymous with the topography beautiful, unspoilt natural environment, away from of Gozo. The hill, or plateau, which is 160 metres everyday routine, tensions and pressures to satisfy above sea level, greets the sun rising from the east both their physical and mental needs. One of the every morning. This explains the rising sun on the picturesque places in Gozo is the village of Nadur. emblem of Nadur. Mother Nature endowed it with enchanting bays, citrus orchards, green fields, abundance of natural We do not have many documents or archaeological spring-water and valleys offering a good living for evidence which could shed light on the colonisation the villagers. of Nadur by its first inhabitants. In December 1990, two Dutch archaeologists Adrian van der A Historical Glimpse Blom and Veronica Veen, unearthed several shreds from an otherwise unspecified triangular The word “Nadur” which in Maltese means “a fields in the Ta’ Kenuna area. This points to the spacious stretch of land situated on a hill top fact that there might have been a community living from where one can watch the surroundings” on the spot around 4000 BC (Bezzina, 2007: 11). is derived from the Arabic word nadar (Erin Nevertheless, the plateau and its surroundings, Serracino-Inglott, 1979: 6 vol. 240). The town’s with a few farm houses scattered here and there, motto “Viġilat” which means “on the lookout”, were in existence for many years well before the is in line with this description. -

Malta & Gozo 7

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Malta & Gozo Gozo & Comino p127 Northern Malta p85 Sliema, St Julian's & Paceville p76 Central Malta Valletta p103 p50 Southern Malta p117 Brett Atkinson PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to VALLETTA . 50 SLIEMA, ST JULIAN’S Malta & Gozo . 4 History . 52 & PACEVILLE . 76 Malta & Gozo’s Top 10 . 8 Sights . 52 Sliema & Around . 78 Need to Know . 14 Courses . 60 St Julian’s & Paceville . 81 What’s New . 16 Tours . .. 60 If You Like… . 17 Eating . 60 NORTHERN MALTA . 85 Month by Month . 19 Drinking & Nightlife . 63 Golden Bay & Itineraries . 22 Entertainment . 67 Għajn Tuffieħa . .. 88 Accommodation . 24 Shopping . 67 Mġarr & Around . 89 Getting Around Around Valletta . 69 Mellieħa & Around . 89 Malta & Gozo . 26 Hal Saflieni Hypogeum & Marfa Peninsula . 92 Activities . 28 Tarxien Temples . 69 Xemxija . 92 Eat & Drink The Three Cities . 70 Like a Local . 38 Buġibba, Qawra & Vittoriosa . 70 St Paul’s Bay . 96 Travel with Children . 43 Senglea . 75 Baħar Iċ-Ċagħaq . 102 Regions at a Glance . .. 47 MACIEJ NICGORSKI / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / NICGORSKI MACIEJ © / 500PX MARTA TRITON FOUNTAIN, VALLETTA P60 DANILOVI / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / DANILOVI BLUE LAGOON, COMINO P148 Contents UNDERSTAND CENTRAL MALTA . 103 GOZO & COMINO . 127 Malta & Gozo Today . 150 Mdina . 106 Gozo . 130 History . 152 Rabat . 110 Victoria (Rabat) . 130 Dingli Cliffs . 112 The Maltese Way Mġarr . 135 of Life . 163 Mosta . 114 Mġarr ix-Xini . 136 5000 Years of Naxxar . 115 Xewkija . 137 Architecture . 167 Birkirkara & the Ta’Ċenċ . 137 Three Villages . 115 Xlendi . 138 Fomm ir-Riħ . 116 SURVIVAL Għarb & San Lawrenz . 139 GUIDE SOUTHERN MALTA . -

Migration, Surnames and Marriage in the Maltese Island of Gozo Around 1900

Journal of Maltese History, 2011/2 Migration, surnames and marriage in the Maltese island of Gozo around 1900. H.V.Wyatt Visiting Lecturer in the School of Philosophy, University of Leeds. Abstract The marriage records in the Public Registry in Gozo have been used to count the. frequency of surnames. Children with poliomyelitis and their controls from the same villages have been traced to their great grand-parents. These records have been used to trace migration to and from the larger island of Malta and the extent of consanguinity in each village. ______________________________________________________ Dr. Wyatt has held research and teaching posts in England, the United States, and the West Bank. He has taught and researched for 2 years in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and for 4 years in Malta. He was previously Honorary Research Fellow in Public Health Medicine at Leeds University. Acknowledgements: I am very grateful to the Peel Medical Research Trust and the Royal Society for travel grants, to all the doctors, parish priests and other clergy who helped me, but especially to Professors H.M.Gilles and A. Scicluna-Spiteri. 35 Journal of Maltese History, 2011/2 Introduction To the north-west of Malta is the smaller island of Gozo (Fig 1), with an area of 67 square kilometres and about one tenth the population of Malta. In November 1942 poliovirus was introduced to the islands from Egypt and more than 420 children were paralysed. There were later, but smaller epidemics, until mass immunisation with the Sabin vaccine ensured that there have been no cases since 1964.