Chinese Multinational Companies in Global R&D and Innovation Rankings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEACHERS' RETIREMENT SYSTEM of the STATE of ILLINOIS 2815 West Washington Street I P.O

Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2020 Performed as Special Assistant Auditors for the Auditor General, State of Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System of the State of Illinois Compliance Examination For the Year Ended June 30, 2020 Table of Contents Schedule Page(s) System Officials 1 Management Assertion Letter 2 Compliance Report Summary 3 Independent Accountant’s Report on State Compliance, on Internal Control over Compliance, and on Supplementary Information for State Compliance Purposes 4 Independent Auditors’ Report on Internal Control over Financial Reporting and on Compliance and Other Matters Based on an Audit of Financial Statements Performed in Accordance with Government Auditing Standards 8 Schedule of Findings Current Findings – State Compliance 10 Supplementary Information for State Compliance Purposes Fiscal Schedules and Analysis Schedule of Appropriations, Expenditures and Lapsed Balances 1 13 Comparative Schedules of Net Appropriations, Expenditures and Lapsed Balances 2 15 Comparative Schedule of Revenues and Expenses 3 17 Schedule of Administrative Expenses 4 18 Schedule of Changes in Property and Equipment 5 19 Schedule of Investment Portfolio 6 20 Schedule of Investment Manager and Custodian Fees 7 21 Analysis of Operations (Unaudited) Analysis of Operations (Functions and Planning) 30 Progress in Funding the System 34 Analysis of Significant Variations in Revenues and Expenses 36 Analysis of Significant Variations in Administrative Expenses 37 Analysis -

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Annual Report 147402 (Zoomlion Eng) 00

中聯重科股份有限公司 ZOOMLION HEAVY INDUSTRY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY CO., LTD. ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Annual Report 147402 (Zoomlion Eng)_00. IFC (eng)_(210x285) \ 14/04/2021 \ X11 \ P. 1 Important notice • The Board of Directors and the Supervisory Board of the Company and its directors, supervisors and senior management warrant that there are no misrepresentation, misleading statements or material omissions in this report and they shall, individually and jointly, accept full responsibility for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents of this report. • All directors attended the Board meeting at which this report was reviewed. Definition Unless the context otherwise requires, the following terms shall have the meanings set out below: “The Company” or “Zoomlion” refers to Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science and Technology Co., Ltd. “Listing Rules” or “Listing Rules of Hong Kong” refers to the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. 147402 (Zoomlion Eng)_00. IFC (eng)_(210x285) \ 14/04/2021 \ X11 \ P. 2 CONTENTS Company Profile 2 Chairman’s Statement 4 Principal Financial Data and Indicators 7 Report of the Board of Directors 10 Management Discussion and Analysis 24 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 34 Significant Events 63 Changes in Share Capital and Shareholders 66 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Employees 71 Share Option Scheme 82 Corporate Governance 86 Independent Auditor’s Report 101 Financial Statements prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards and Notes 109 147402 (Zoomlion Eng)_01. Company Profile_(210x285) \ 13/04/2021 \ X11 \ P. 2 Company Profile I. Company Information Company name (in Chinese): 中聯重科股份有限公司 Chinese abbreviation: 中聯重科 Company name (in English): Zoomlion Heavy Industry Science And Technology Co., Ltd.* English abbreviation: Zoomlion Legal representative of the Company: Zhan Chunxin Secretary of the Board of Directors/Company Secretary: Yang Duzhi Representative of securities affairs: Xu Yanlai Contact address: No. -

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 01 October 2020 FTSE Value Stocks China A Share Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 September 2020 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) Agricultural Bank of China (A) 4.01 CHINA Fuyao Glass Group Industries (A) 1.43 CHINA Seazen Holdings (A) 0.81 CHINA Aisino Corporation (A) 0.52 CHINA Gemdale (A) 1.37 CHINA Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Group (A) 1.63 CHINA Anhui Conch Cement (A) 3.15 CHINA GoerTek (A) 2.12 CHINA Shenwan Hongyuan Group (A) 1.11 CHINA AVIC Investment Holdings (A) 0.61 CHINA Gree Electric Appliances Inc of Zhuhai (A) 7.48 CHINA Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town Holdings 0.66 CHINA Bank of China (A) 2.23 CHINA Guangdong Haid Group (A) 1.24 CHINA (A) Bank Of Nanjing (A) 1.32 CHINA Guotai Junan Securities (A) 1.99 CHINA Sichuan Chuantou Energy (A) 0.71 CHINA Bank of Ningbo (A) 2 CHINA Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology (A) 3.56 CHINA Tbea (A) 0.86 CHINA Beijing Dabeinong Technology Group (A) 0.56 CHINA Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development 1.49 CHINA Tonghua Dongbao Medicines(A) 0.59 CHINA China Construction Bank (A) 1.83 CHINA (A) Weichai Power (A) 2.09 CHINA China Life Insurance (A) 2.14 CHINA Hengtong Optic-Electric (A) 0.59 CHINA Wuliangye Yibin (A) 9.84 CHINA China Merchants Shekou Industrial Zone 1.03 CHINA Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (A) 3.5 CHINA XCMG Construction Machinery (A) 0.73 CHINA Holdings (A) Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial(A) 6.32 CHINA Xinjiang Goldwind Science&Technology (A) 0.74 -

Signature Redacted I MIT Sino in School of Management May 6, 2016

Individual Investors, Social Media and Chinese Stock Market: a Correlation Study By Yonghui Wu B.E., Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2007 M.E., Shanghai Jiao Tong University, 2010 SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT STUDIES MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 082016 JUNE 2016 LIBRARIES @2016 Yonghui Wu. All rights reserved. ARCHIVES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: Signature redacted I MIT Sino in School of Management May 6, 2016 Certified by: Signature redacted Erik Brynjolfsson Schussel Family Professor Thesis Supervisor Signature redacted____ Accepted by: Rodrigo S. Verdi Associate Professor of Accounting Program Director, M.S. in Management Studies Program MIT Sloan School of Management Individual Investors, Social Media and Chinese Stock Market: a Correlation Study By Yonghui Wu Submitted to MIT Sloan School of Management on May 6, 2016 in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Management Studies. ABSTRACT Chinese stock market is a unique financial market where heavy involvement of individual investors exists. This article explores how the sentiment expressed on social media is correlated with the stock market in China. Textual analysis for posts from one of the most popular social media in China is conducted based on Hownet and NTUSD, two most commonly used sentiment Chinese dictionaries. -

An Introduction to CPU and DSP Design in China

SCIENCE CHINA Information Sciences . REVIEW . January 2016, Vol. 59 012101:1–012101:8 doi: 10.1007/s11432-015-5431-6 An introduction to CPU and DSP design in China Weiwu HU1,2,4 *, Yifu ZHANG1,2,3 & Jie FU1,2,3 1State Key Laboratory of Computer Architecture, Institute of Computing Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; 2Institute of Computing Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; 3School of Computer and Control Engineering, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China; 4Loongson Technology Corporation Limited, Beijing 100195, China Received June 26, 2015; accepted August 10, 2015; published online October 29, 2015 Abstract In recent years, China has witnessed considerable achievements in the production of domestically- designed CPUs and DSPs. Owing to fifteen years of hard work that began in 2001, significant progress has been made in Chinese domestic CPUs and DSPs, primarily represented by Loongson and ShenWei processors. Furthermore parts of the CPU design techniques are comparable to the world’s most advanced designs. A special issue published in Scientia Sinica Informationis in April 2015, is dedicated to exhibiting the technical advancements in Chinese domestically-designed CPUs and DSPs. The content in this issue describes the design and optimization of high performance processors and the key technologies in processor development; these include high-performance micro-architecture design, many-core and multi-core design, radiation hardening design, high- performance physical design, complex chip verification, and binary translation technology. We hope that the articles we collected will promote understanding of CPU/DSP progress in China. Moreover, we believe that the future of Chinese domestic CPU/DSP processors is quite promising. -

China 2025 16

China | Equity Strategy China 14 December 2014 EQUITY RESEARCH China The Year of the Ram: Stars Aligned for a Historic Bull Run Key Takeaway The Ram, the Bull and the Heavenly Twins – the stars are now aligned for China’s historic bull-run. China's stock market offers massive untapped potential given the high savings rate and low penetration. “Keeping Growth Steady” is a top priority for 2015; we expect SHCOMP and HSCEI to test 4,050 and 15,420, up 38% and 37% from current levels. As confidence gains momentum, volatility becomes the investors’ best friend. CHINA China Gallops into a Historic Bull Run. On Nov 20, 2013, we wrote “The Year of the Horse will see China unleash its full potential, as President Xi ushers in a new era of profound change.” “We expect capital markets to gradually gain confidence in China’s ability to drive fundamental reforms and expect Chinese stocks to enter a historic multi-year bull run.” Indeed, 2014 has been a remarkable year. As of Dec.12, SHCOMP surged 39% to 2938, breaking a seven-year bearish trend to become the best performing index in the world. China Stock Market: Massive Untapped Potential. According to China Household Finance Survey, property accounted for 66.4% of total Chinese household assets in 2013. Financial assets accounted for a mere 10.1% of household wealth. While over 61% of Chinese families have bank deposits, only 6.5% of them invested in the stock market. Given China’s high savings rate and low stock market penetration, we believe the A-share market offers significant upside potential. -

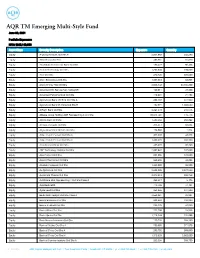

AQR TM Emerging Multi-Style Fund June 30, 2021

AQR TM Emerging Multi-Style Fund June 30, 2021 Portfolio Exposures NAV: $685,149,993 Asset Class Security Description Exposure Quantity Equity A-Living Services Ord Shs H 2,001,965 402,250 Equity Absa Group Ord Shs 492,551 51,820 Equity Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Ord Shs 180,427 96,468 Equity Accton Technology Ord Shs 1,292,939 109,000 Equity Acer Ord Shs 320,736 305,000 Equity Adani Enterprises Ord Shs 1,397,318 68,895 Equity Adaro Energy Tbk Ord Shs 2,003,142 24,104,200 Equity Advanced Info Service Non-Voting DR 199,011 37,300 Equity Advanced Petrochemical Ord Shs 419,931 21,783 Equity Agricultural Bank of China Ord Shs A 288,187 614,500 Equity Agricultural Bank Of China Ord Shs H 482,574 1,388,000 Equity Al Rajhi Bank Ord Shs 6,291,578 212,576 Equity Alibaba Group Holding ADR Representing 8 Ord Shs 33,044,794 145,713 Equity Alinma Bank Ord Shs 1,480,452 263,892 Equity Ambuja Cements Ord Shs 305,517 66,664 Equity Anglo American Platinum Ord Shs 174,890 1,514 Equity Anhui Conch Cement Ord Shs A 307,028 48,323 Equity Anhui Conch Cement Ord Shs H 1,382,025 260,500 Equity Arab National Bank Ord Shs 485,970 80,290 Equity ASE Technology Holding Ord Shs 2,982,647 742,000 Equity Asia Cement Ord Shs 231,096 127,000 Equity Aspen Pharmacare Ord Shs 565,696 49,833 Equity Asustek Computer Ord Shs 1,320,000 99,000 Equity Au Optronics Ord Shs 2,623,295 3,227,000 Equity Aurobindo Pharma Ord Shs 3,970,513 305,769 Equity Autohome ADS Representing 4 Ord Shs Class A 395,017 6,176 Equity Axis Bank GDR 710,789 14,131 Equity Ayala Land Ord Shs 254,266 344,300 -

956830 Deliverable D2.1 Initial Vision and Requirement Report

European Core Technologies for future connectivity systems and components Call/Topic: H2020 ICT-42-2020 Grant Agreement Number: 956830 Deliverable D2.1 Initial vision and requirement report Deliverable type: Report WP number and title: WP2 (Strategy, vision, and requirements) Dissemination level: Public Due date: 31.12.2020 Lead beneficiary: EAB Lead author(s): Fredrik Tillman (EAB), Björn Ekelund (EAB) Contributing partners: Yaning Zou (TUD), Uta Schneider (TUD), Alexandros Kaloxylos (5G IA), Patrick Cogez (AENEAS), Mohand Achouche (IIIV/Nokia), Werner Mohr (IIIV/Nokia), Frank Hofmann (BOSCH), Didier Belot (CEA), Jochen Koszescha (IFAG), Jacques Magen (AUS), Piet Wambacq (IMEC), Björn Debaillie (IMEC), Patrick Pype (NXP), Frederic Gianesello (ST), Raphael Bingert (ST) Reviewers: Mohand Achouche (IIIV/Nokia), Jacques Magen (AUS), Yaning Zou (TUD), Alexandros Kaloxylos (5G IA), Frank Hofmann (BOSCH), Piet Wambacq (IMEC), Patrick Cogez (AENEAS) D 2.1 – Initial vision and requirement report Document History Version Date Author/Editor Description 0.1 05.11.2020 Fredrik Tillman (EAB) Outline and contributors 0.2 19.11.2020 All contributors First complete draft 0.3 18.12.2020 All contributors Second complete draft 0.4 21.12.2020 Björn Ekelund Third complete draft 1.0 21.12.2020 Fredrik Tillman (EAB) Final version List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Denotation 5G 5th Generation of wireless communication 5G PPP The 5G infrastructure Public Private Partnership 6G 6th Generation of wireless communication AI Artificial Intelligence ASIC Application -

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

報告編號: 公司註冊處電子查冊服務 日期 : REPORT ID: RPS350 COMPANIES REGISTRY ELECTRONIC SEARCH SERVICES DATE: 28-2-2011 根據《公司條例》(第32章) 成立∕註冊的新公司 頁數: Newly Incorporated / Registered Companies under the Companies Ordinance (Cap. 32) PAGE: 1 本報告涵蓋的日期(日/月/年): Period Covered (By Date)(D/M/Y): 21/02/2011 - 27/02/2011 序號 公司名稱 公司註冊編號 成立∕註冊日期(日-月-年) Sequence No. Company Name C.R. Number Date of Incorporation / Registration(D-M-Y) 1 1st ATELIER LIMITED 1562496 21-2-2011 壹號創美有限公司 2 2B DEVELOPMENT LIMITED 1563538 23-2-2011 3 3B REFINERY LIMITED 1565086 24-2-2011 4 3D GLOVES CO., LIMITED 1564568 24-2-2011 威勤防護手套有限公司 5 A PLUS INDUSTRIAL (CHINA) LIMITED 1564845 24-2-2011 時駿實業有限公司 6 A&O CARGO (HK) LIMITED 1563039 22-2-2011 華優達貨運(香港)有限公司 7 A.R.M. ASIA CO., LIMITED 1562451 21-2-2011 8 AB2 Cloud Limited 1563866 23-2-2011 9 ABIZ LIMITED 1566123 27-2-2011 10 ABLE ACCORD LIMITED 1565456 25-2-2011 11 ABLE CHINA INTERNATIONAL GROUP LIMITED 1563286 22-2-2011 華誠國際集團(中國)有限公司 12 ABLE EAGLE CORPORATION LIMITED 1564381 24-2-2011 新鷹有限公司 13 ABLE FORTUNE HOLDINGS LIMITED 1564866 24-2-2011 成福集團有限公司 報告編號: 公司註冊處電子查冊服務 日期 : REPORT ID: RPS350 COMPANIES REGISTRY ELECTRONIC SEARCH SERVICES DATE: 28-2-2011 根據《公司條例》(第32章) 成立∕註冊的新公司 頁數: Newly Incorporated / Registered Companies under the Companies Ordinance (Cap. 32) PAGE: 2 本報告涵蓋的日期(日/月/年): Period Covered (By Date)(D/M/Y): 21/02/2011 - 27/02/2011 序號 公司名稱 公司註冊編號 成立∕註冊日期(日-月-年) Sequence No. Company Name C.R. -

Schedule of Investments (Unaudited) Blackrock Advantage Emerging Markets Fund January 31, 2021 (Percentages Shown Are Based on Net Assets)

Schedule of Investments (unaudited) BlackRock Advantage Emerging Markets Fund January 31, 2021 (Percentages shown are based on Net Assets) Security Shares Value Security Shares Value Common Stocks China (continued) China Life Insurance Co. Ltd., Class H .................. 221,000 $ 469,352 Argentina — 0.0% China Longyuan Power Group Corp. Ltd., Class H ....... 52,000 76,119 (a) 313 $ 60,096 Globant SA .......................................... China Mengniu Dairy Co. Ltd.(a) ......................... 15,000 89,204 Brazil — 4.9% China Merchants Bank Co. Ltd., Class H ................ 36,000 275,683 Ambev SA ............................................. 236,473 653,052 China Overseas Land & Investment Ltd.................. 66,500 151,059 Ambev SA, ADR ....................................... 94,305 263,111 China Pacific Insurance Group Co. Ltd., Class H......... 22,000 90,613 B2W Cia Digital(a) ...................................... 20,949 315,188 China Railway Group Ltd., Class A ...................... 168,800 138,225 B3 SA - Brasil Bolsa Balcao............................. 33,643 367,703 China Resources Gas Group Ltd. ....................... 30,000 149,433 Banco do Brasil SA..................................... 15,200 94,066 China Resources Land Ltd. ............................. 34,000 134,543 BRF SA(a).............................................. 22,103 85,723 China Resources Pharmaceutical Group Ltd.(b) .......... 119,500 62,753 BRF SA, ADR(a) ........................................ 54,210 213,045 China Vanke Co. Ltd., Class A .......................... 67,300 289,157 Cia de Saneamento de Minas Gerais-COPASA .......... 52,947 150,091 China Vanke Co. Ltd., Class H .......................... 47,600 170,306 Duratex SA ............................................ 19,771 71,801 CITIC Ltd............................................... 239,000 186,055 Embraer SA(a).......................................... 56,573 90,887 Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., Class A .... 1,700 92,204 Gerdau SA, ADR ...................................... -

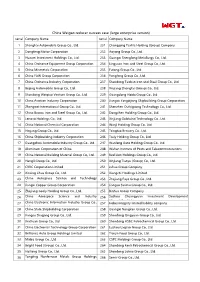

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

Semi-Annual Report March 31, 2021

The Advisors’ Inner Circle Fund III Rayliant Quantamental China Equity ETF SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT MARCH 31, 2021 Investment Adviser: Rayliant Asset Management THE ADVISORS’ INNER CIRCLE FUND III RAYLIANT QUANTAMENTAL CHINA EQUITY ETF MARCH 31, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Schedule of Investments 1 Statement of Assets and Liabilities 5 Statement of Operations 6 Statement of Changes in Net Assets 7 Financial Highlights 8 Notes to Financial Statements 9 Disclosure of Fund Expenses 26 Approval of Investment Advisory Agreement 28 The Fund files its complete schedule of investments with the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) for the first and third quarters of each fiscal year as an exhibit to its reports on Form N-PORT. The Fund’s Form N-PORT is available on the SEC’s website at https://www.sec.gov, and may be reviewed and copied at the SEC’s Public Reference Room in Washington, DC. Information on the operation of the Public Reference Room may be obtained by calling 1-800-SEC-0330. A description of the policies and procedures that the Fund uses to determine how to vote proxies relating to Fund securities, as well as information relating to how a Fund voted proxies relating to fund securities during the most recent 12-month period ended June 30, is available (i) without charge, upon request, by calling 1-866-898-1688; and (ii) on the SEC’s website at https://www.sec.gov. THE ADVISORS’ INNER CIRCLE FUND III RAYLIANT QUANTAMENTAL CHINA EQUITY ETF MARCH 31, 2021 (UNAUDITED) SECTOR WEIGHTINGS† 27.6% Financials 15.0% Consumer Staples 11.9% Consumer Discretionary 11.2% Industrials 11.0% Information Technology 7.6% Health Care 6.2% Materials 3.3% Utilities 3.3% Energy 1.8% Communication Services 1.1% Real Estate † Percentages are based on total investments.