This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tissue and Cell

TISSUE AND CELL AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.1 • Abstracting and Indexing p.1 • Editorial Board p.1 • Guide for Authors p.3 ISSN: 0040-8166 DESCRIPTION . Tissue and Cell is devoted to original research on the organization of cells, subcellular and extracellular components at all levels, including the grouping and interrelations of cells in tissues and organs. The journal encourages submission of ultrastructural studies that provide novel insights into structure, function and physiology of cells and tissues, in health and disease. Bioengineering and stem cells studies focused on the description of morphological and/or histological data are also welcomed. Studies investigating the effect of compounds and/or substances on structure of cells and tissues are generally outside the scope of this journal. For consideration, studies should contain a clear rationale on the use of (a) given substance(s), have a compelling morphological and structural focus and present novel incremental findings from previous literature. IMPACT FACTOR . 2020: 2.466 © Clarivate Analytics Journal Citation Reports 2021 ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING . Scopus PubMed/Medline Cambridge Scientific Abstracts Current Awareness in Biological Sciences Current Contents - Life Sciences Embase Embase Science Citation Index Web of Science EDITORIAL BOARD . Editor Pietro Lupetti, University of Siena, Siena, Italy AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK 1 Oct 2021 www.elsevier.com/locate/tice 1 Managing Editor Giacomo Spinsanti, University of Siena, -

The Rewards of Platform Unity: Moving to One Repository at Universidad De La Salle Delivers Benefits

Case Study The rewards of platform unity: moving to one repository at Universidad de La Salle delivers benefits To better support the mission that drives Colombia’s Universidad de La Salle — to generate knowledge that will transform Colombian society by contributing to equity, the defense of life and human development — the university recognized the need to combine three separate digital platforms into a single unifying online presence while simultaneously addressing a long list of technical challenges. After considering several options, it identified Digital Commons as the perfect fit for its needs. This case study charts the university’s decision-making process, the rewards it has subsequently reaped and eight tips for other institutions embarking on a digital repository journey. Introduction Founded in 1964, Universidad de La Salle1 is a private Catholic the other its digital educative resources. So, a cross-department institution with around 14,000 students and 700 postgraduates task force set out to find a single solution that would provide enrolled in a wide array of courses and degree programs. It them with key items on their wish list: is rated a “High Quality University” by Colombia’s National Accreditation Council2 (CNA). Back in 2018, the institution’s five • One entry point to the university’s intellectual output journals were stored on Public Knowledge Project’s Open Journal • Support for the full journal-publishing cycle Systems (OJS) platform. Initially, OJS ticked many boxes for the (including peer review) journals team, as Editorial Head Alfredo Morales recalls: “We • Robust customer support were able to consolidate all our titles, standardize publishing criteria and increase visibility inside and outside the university.” • Effective SEO and indexing of journal articles in Google Scholar • Standardization of metadata But the team also encountered issues that impacted their productivity and content discoverability. -

Get Noticed Promoting Your Article for Maximum Impact Get Noticed 2 GET NOTICED

Get Noticed Promoting your article for maximum impact GET NOTICED 2 GET NOTICED More than one million scientific articles are published each year, and that number is rising. So it’s increasingly important for you to find ways to make your article stand out. While there is much that publishers and editors can do to help, as the paper’s author you are often best placed to explain why your findings are so important or novel. This brochure shows you what Elsevier does and what you can do yourself to ensure that your article gets the attention it deserves. GET NOTICED 3 1 PREPARING YOUR ARTICLE SEO Optimizing your article for search engines – Search Engine Optimization (SEO) – helps to ensure it appears higher in the results returned by search engines such as Google and Google Scholar, Elsevier’s Scirus, IEEE Xplore, Pubmed, and SciPlore.org. This helps you attract more readers, gain higher visibility in the academic community and potentially increase citations. Below are a few SEO guidelines: • Use keywords, especially in the title and abstract. • Add captions with keywords to all photographs, images, graphs and tables. • Add titles or subheadings (with keywords) to the different sections of your article. For more detailed information on how to use SEO, see our guideline: elsevier.com/earlycareer/guides GIVE your researcH THE IMpact it deserVes Thanks to advances in technology, there are many ways to move beyond publishing a flat PDF article and achieve greater impact. You can take advantage of the technologies available on ScienceDirect – Elsevier’s full-text article database – to enhance your article’s value for readers. -

Sciencedirect ® Sciencedirect Books: High Impact, Relevant Content

ScienceDirect ® ScienceDirect Books: High impact, relevant content These days, a world of information is at our fingertips. Simple online searches return millions of pages that claim to provide expert, timely information. But we’ve all had the experience of wondering if the information is trustworthy, accurate and the best to address our needs. Even casual web searchers are left wondering how to decipher the irrelevant information that fills online search result pages, so what’s a serious researcher to do in a world of overwhelming content and underwhelming relevancy? Elsevier offers greater clarity and insights for researchers by putting their needs first. ScienceDirect: A maximum impact, trusted research solution that delivers ScienceDirect, Elsevier’s leading online full-text information solution, is more than just a research destination for scientists; it’s a continuously evolving, dynamic repository that is constantly updated with the very latest research data available on a variety of subjects. Using the latest technology, the platform provides users with the answers they need, when they need them across a broad range of topics in science, technology and health, helping users attain a greater depth of information than other research solutions provide. Our data driven approach A user focused perspective based on the workflow and understanding the needs of researchers to build our publishing strategy Elsevier offers greater clarity and insights for researchers decisions. By providing data and analysis of their by putting their needs first. A wide range of relevant institution’s usage behavior on ScienceDirect to identify content combined with cutting-edge technology on the content gaps, a clear picture of in-demand content ScienceDirect platform provides quick, easily accessible emerges. -

Information for Authors

Information for Authors The Lancet is an international general medical journal that will consider any original contribution that advances or illuminates medical science or practice, or that educates or entertains the journal’s readers. Whatever you have written, remember that it is the general reader whom you are trying to reach. One way to find out if you have succeeded is to show your draft to colleagues in other specialties. If they do not understand, neither, very probably, will The Lancet’s staff or readers. Manuscripts must be solely the work of the author(s) stated, must not have been previously published elsewhere, and must not be under consideration by another journal. For randomised controlled trials or research papers judged to warrant fast dissemination, The Lancet will publish a peer-reviewed manuscript within 4 weeks of receipt (see Swift+ and Fast-track publication). If you wish to discuss your proposed fast-track submission with an editor, please call one of the editorial offices in London (+44 [0] 20 7424 4950), New York (+1 212 633 3667), or Beijing (+86 10 852 08872). The Lancet is a signatory journal to the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Recommendations for the Medical Journals, issued by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE Recommendations), and to the Committee Conduct, Reporting, Editing, on Publication Ethics (COPE) code of conduct for editors. We follow COPE’s guidelines. and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals http://www.icmje.org If your question is not addressed on these pages then the journal’s editorial staff in London (+44 [0] 20 7424 4950), New York (+1 212 633 3810), or Beijing (+86 10 852 08872) will be pleased to help (email [email protected]). -

Elsevier, Bepress, and a Glimpse at the Future of Scholarly Communication Christine L Ferguson, Murray State University

Murray State University From the SelectedWorks of Cris Ferguson 2018 Elsevier, bepress, and a Glimpse at the Future of Scholarly Communication Christine L Ferguson, Murray State University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/christine-l-ferguson/45/ Balance Point Elsevier, bepress, and a Glimpse at the Future of Scholarly Communication Cris Ferguson, Column Editor Director of Technical Services, Waterfield Library, Murray State University, Murray, KY 42071; phone: 270-809-5607; email: [email protected]; ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000- 0001-8410-6010 Keywords Elsevier; bepress; open access; Penn Libraries; Digital Commons; scholarly communications Abstract The acquisition of bepress by Elsevier in August 2017, while unpopular among many librarians, provides both companies opportunities for expansion and growth. This Balance Point column outlines some of the benefits to both companies and the reaction by the library community. Also addressed is the announcement by the Penn Libraries that they are searching for a new open source repository potentially to replace bepress’s Digital Commons. The column concludes with some discussion of Elsevier’s relationship with open access content and the impact of the acquisition on the scholarly communications infrastructure. On August 2, 2017, Elsevier announced its acquisition of bepress, the provider of the Digital Commons institutional repository platform. Digital Commons “allows institutions to collect, organize, preserve and disseminate their intellectual output, including preprints, working papers, journals or specific articles, dissertations, theses, conference proceedings and a wide variety of other data” (Elsevier, August 2, 2017). bepress’s other major service, the Experts Gallery Suite, focuses on showcasing the expertise and scholarship of faculty. At the time Elsevier acquired the company, bepress had more than 500 customers using Digital Commons, and over 100 institutions using the Experts Gallery Suite. -

Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering

CURRENT OPINION IN CHEMICAL ENGINEERING AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 2211-3398 DESCRIPTION . Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering is devoted to bringing forth short and focused review articles written by experts on current advances in different areas of chemical engineering. Only invited review articles will be published. The goals of each review article in Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering are: 1. To acquaint the reader/researcher with the most important recent papers in the given topic. 2. To provide the reader with the views/opinions of the expert in each topic. The reviews are short (about 2500 words or 5-10 printed pages with figures) and serve as an invaluable source of information for researchers, teachers, professionals and students. The reviews also aim to stimulate exchange of ideas among experts. Themed sections: Each review will focus on particular aspects of one of the following themed sections of chemical engineering: 1. Nanotechnology 2. Energy and environmental engineering 3. Biotechnology and bioprocess engineering 4. Biological engineering (covering tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, drug delivery) 5. Separation engineering (covering membrane technologies, adsorbents, desalination, distillation etc.) 6. Materials engineering (covering biomaterials, inorganic especially ceramic materials, nanostructured materials). 7. Process systems engineering 8. Reaction engineering and catalysis. Selection of the topics to be reviewed: Section Editors of each themed section are authorities in the field and are selected by the Editors of the journal. They divide their section into a number of topics ensuring that the field is comprehensively covered and that all issues of current importance are emphasized. -

CAGEO Gfa April2010.Pdf

Guide for Authors – Computers & Geosciences It can be advantageous to print this "Guide for Authors" section for reference during the subsequent stages of article preparation. Summary of Important Items when submitting a manuscript 1) Be certain that your manuscript contains suitable material for the journal (computing methods in the physical geosciences). Out of scope articles will be returned to authors without review. Please read the Aims & Scope of the journal. 2) Please read the Elsevier web page on Publishing Ethics: www.elsevier.com/publishingethicskit. 3) Please provide a covering letter explaining the contribution of the manuscript. 4) Grammar, spelling and accuracy are considered as the most important screening criterion. If your manuscript contains errors in English, it will be returned. Non- English speaking authors are encouraged to have their manuscript checked and edited by a native English speaker. Alternatively, the use of language editing services can be used to improve the English of a manuscript. 5) Manuscripts, which do not meet the novelty, significance, and competence criteria (Aims & Scope of the journal) will be returned to authors at any stage, at the discretion of the Editor. 6) References must follow the format as stipulated in this guide. Your manuscript will be returned if the format of the references is not correct. 7) Ensure that figures are adequately labelled (coordinates, scale bar, orientation) and the resolution is sufficient for publication scale. 8) Choose the appropriate article type (Research, Application, Review or Short Note articles – see Aims & Scope). Ensure your manuscript falls within the word limit for the article type that you choose. -

Elsevier Research Platforms

| 1 | Scopus Trainer : Nattaphol Sisuruk Elsevier Training Consultant, Research Solutions E-mail : [email protected] | 2 | ELSEVIER is a leading Science & Health Information Provider CONTENTPROVISION ‘E’ CONTENT PROVISION RESEARCH MGMT SEARCH & DISCOVERY /PROMOTION TOOLS Niels Louis Alexander Albert George F. John C. Roger D. Craig C Mello Smoot Medicine Bohr Physics Pasteur Fleming Einstein Mather Kornberg Physics Physics (Chemistry) Medicine Physics Chemistry 2 | 3 | Globally recognised high impact content Disseminate Global Elsevier Citations Total STM reference, publication & citations Elsevier share Coverage: Approximately 5,000 publishers Other Get cited Publisher A Publisher B CertifyCertify Investigate Global Elsevier Publications Global References to Elsevier Elsevier Publish Cite Elsevier Other Publisher A Other Publisher A Publisher B 24 Citations Per Paper: Publisher B 27% of all references Global team 2010-2014 74 offices in 24 countries Publisher References Publications Citations 7,000 Journal Editors Elsevier 56,304,346 1,888,115 45,990,748 Publisher A 15,738,334 1,221,036 22,374,220 70,000 Editorial Board Members Publisher B 23,064,330 747,976 18,298,048 600,000 authors Other 116,371,011 5,261,600 95,192,376 Totals 211,478,021 9,118,727 181,855,392 | 4 | Elsevier Research Platforms : Researchers seek a digital environment where ideas can be exchanged, examined, and applied with tools that empower STM knowledge. To find and analyze data from over 5000 publishers Access the leading eBooks and journal articles published by Elsevier Manage your research and showcase your profile via free services :These platforms make data and content easier to search, access, analyze, and share. -

Quick Start Guide

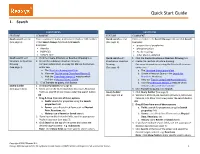

Quick Start Guide 1. Search SUBSTANCES REACTIONS FEATURE COMMENT FEATURE COMMENT Quick search as text Enter a substance name, molecular formula or CAS number Quick search as text Enter a term(s) in the Search Reaxys field and click Search. (See page 3) in the Search Reaxys field and click Search. (See page 3) Examples: Examples: preparation of porphyrine Atenolol phosphorylation Pt(PPh3)3 Suzuki coupling 102625-70-7 Adler phenol oxidation Quick search with 1. Click the Create Structure or Reaction Drawing box. Quick search with 1. Click the Create Structure or Reaction Drawing box. Structure or Reaction 2. Create the substance structure drawing. Structure or Reaction 2. Create the reaction structure drawing. Drawing For more information on using the Marvin JS structure Drawing For more information on using the Marvin JS structure (See page 4) editor see: (See page 4) editor see: a. The Structure drawing workflow. a. The Structure drawing workflow. b. View our Tips for using ChemAxon Marvin JS. b. Create a Reaction Query in the Search for c. Visit the ChemAxon Marvin JS website which Reactions Workflow. includes a MarvinJS User’s Guide. c. View our Tips for using ChemAxon Marvin JS 3. Click Transfer to query, click Search. d. Visit the ChemAxon Marvin JS website which Query builder 1. Click Query builder (See page 6). includes a MarvinJS User’s Guide (See page 5 & 6) 2. Select one of the Quick Querylets (Structure, Molecular 3. Click Transfer to query, click Search. Formula, CAS RN or Doc Index) under the search button. Query builder 1. -

Current Opinion in Plant Biology

CURRENT OPINION IN PLANT BIOLOGY AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.4 ISSN: 1369-5266 DESCRIPTION . Excellence paves the way With Current Opinion in Plant Biology Current Opinion in Plant Biology builds on Elsevier's reputation for excellence in scientific publishing and long-standing commitment to communicating high quality reproducible research. It is part of the Current Opinion and Research (CO+RE) suite of journals. All CO+RE journals leverage the Current Opinion legacy - of editorial excellence, high-impact, and global reach - to ensure they are a widely read resource that is integral to scientists' workflow. Expertise: Editors and Editorial Board bring depth and breadth of expertise and experience to the journal. Discoverability: Articles get high visibility and maximum exposure on an industry-leading platform that reaches a vast global audience. The Current Opinion journals were developed out of the recognition that it is increasingly difficult for specialists to keep up to date with the expanding volume of information published in their subject. In Current Opinion in Plant Biology, we help the reader by providing in a systematic manner: 1. The views of experts on current advances in plant biology in a clear and readable form. 2. Evaluations of the most interesting papers, annotated by experts, from the great wealth of original publications. Division of the subject into sections: The subject of plant biology is divided into themed sections which are reviewed regularly to keep them relevant. -

Journal of Molecular Biology

JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AUTHOR INFORMATION PACK TABLE OF CONTENTS XXX . • Description p.1 • Audience p.2 • Impact Factor p.2 • Abstracting and Indexing p.2 • Editorial Board p.2 • Guide for Authors p.6 ISSN: 0022-2836 DESCRIPTION . Journal of Molecular Biology (JMB) provides high quality, comprehensive and broad coverage in all areas of molecular biology. The journal publishes original scientific research papers that provide mechanistic and functional insights and report a significant advance to the field. The journal encourages the submission of multidisciplinary studies that use complementary experimental and computational approaches to address challenging biological questions. Research areas include but are not limited to: Biomolecular interactions, signaling networks, systems biology Cell cycle, cell growth, cell differentiation Cell death, autophagy Cell signaling and regulation Chemical biology Computational biology, in combination with experimental studies DNA replication, repair, and recombination Development, regenerative biology, mechanistic and functional studies of stem cells Epigenetics, chromatin structure and function Gene expression Receptors, channels, and transporters Membrane processes Cell surface proteins and cell adhesion Methodological advances, both experimental and theoretical, including databases Microbiology, virology, and interactions with the host or environment Microbiota mechanistic and functional studies Nuclear organization Post-translational modifications, proteomics Processing and function of biologically