The Copper Mines of Cornwall: Property and Profit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Pigot's 1830 Bodmin & Wadebridge.Docx

Extract from Pigot’s Directory of Cornwall, 1830 (pages 135‐136) Bodmin and Wadebridge Bodmin is a borough, market town and parish, in the hundred of Trigg; 234 miles from London, 62 from Exeter, 60 from the Land’s End, 34 from Falmouth, and six from Lostwithiel. It is situated nearly in the centre of the county, between two hills, and consists chiefly of one long street, running east and west. This town must at one time have been of much more consequence, and greater magnitude, than at the present day; for it formerly contained a priory, cathedral, and thirteen churches or free chapels, of which the foundations and sites of some are still to be distinguished. The present church is the largest in the county, and is handsome within, but externally irregularly built. The living is a vicarage, in the gift of Lord de Dunstanville; and the Rev. J. Wallis is the present incumbent. Here are three chapels for dissenters, and a free grammar school, founded and endowed by Queen Elizabeth. Bodmin must have been very early constituted a borough; for in an ancient record it appears that the burgesses were fined 100 shillings, in the 26th year of Henry II, for setting up a guild without a warrant. The corporate body, as created by the last charter, granted in 1798, consists of a mayor, 12 aldermen, 24 capital burgesses and a recorder. The right of returning members to Parliament is vested in the corporation; the mayor is the returning officer; and the present representatives are, David Gilbert, Esq. -

Camelford Exploration and Research

Out and about Local attractions Welcome to •Boscastle Visitor Centre There is much to enjoy at Boscastle and the Visitor Centre should be your first port of call for all the information you need to discover the opportunities for further local Camelford exploration and research. 01840 250010 www.visitboscastleandtintagel.com Caravan Club Site •Bodmin & Wenford •Lanhydrock House and Garden Steam Railway One of the most beautiful National Trust Discover the excitement and nostalgia of properties in Cornwall, Lanhydrock House steam travel with a journey back in time and gardens are a must-see all year round. on the Bodmin & Wenford Railway Superbly set in wooded parkland of 1,000 – Cornwall’s only full-size railway still acres and encircled by a garden of rare operated by steam locomotives. shrubs and trees. 0845 125 9678 01208 265950 www.bodminandwenfordrailway.co.uk www.nationaltrust.org.uk •The Eden Project With a worldwide reputation Eden barely •Carnglaze Slate Caverns needs an introduction, but this epic Three underground caverns set in 6.5 destination definitely deserves a day of acres of wooded hillside of the Loveny your undivided attention. Dubbed the Valley. Take a tour through the caverns ‘8th Wonder of the World’, there’s always of cathedral proportions, hand-created something new to see – go again & again! by local slate miners. Within the complex 01726 811911 is the famous subterranean lake with its www.edenproject.com crystal clear blue/green water. 01579 320251 •Pencarrow House & Gardens www.carnglaze.com 50 acres of beautiful grounds – the perfect place for everyone including the dog! Also an Historic Georgian house Activities containing a superb collection of pictures, Get to know your site furniture and porcelain. -

The Lanhydrock 10

Presents THE LANHYDROCK 10 Saturday 8 October 2016, 3.30pm race start MTRS Race 3, 2016/17 series UKA race licence applied for 10 mile multi-terrain run through the estate Bring the family and enjoy the whole property for the day. Visit www.nationaltrust.org.uk/lanhydrock for opening times and Directions: Follow the brown visitor road signs to National prices. National Trust members enter Lanhydrock House & Trust Lanhydrock and park in the main car park. After park- Gardens and park for FREE. ing, follow the signs on foot towards Lanhydrock House & Lanhydrock house, gardens, estate, cafe, restaurant, shop, Gardens. Registration tent by the plant centre next to the plant sales, cycle trails and cycle hire. car park, open from 2pm. Surname: ………………………………….. Forename: ………………………………......... Please write all details CLEARLY Address: ..................................................................... Male/Female: ....................................................... ................................................................................................ Date of Birth: ……….....………………………….. ................................................................................................ Tel. number: ……………...................................... Post code: ……………………………........................... Male Under 35 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75+ Female Under 35 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70+ Please circle your age group on race day (minimum age 17): Email address: …………......................................................................................................................................... -

Lanhydrock Golf Club Open Events 2020

Lanhydrock Golf Club Open Events 2020 Thursday 16th April – Seniors Spring Open Three Man Team BBB Stableford. Open to players aged 55 and over. Best two scores to count on each hole. 90% - Max h’cap 24. Entry includes, golf, prizes and two course carvery. Visitors £27.00 (members £20.00). Sunday 19th April – Men’s Spring Open Pairs BBB Stableford. 90% - Max H’cap 24. Entry includes, golf, prizes and Two Course Carvery. Visitors £27.00 (members £20.00). Tuesday 26th May – Junior Open Telegraph Qualifier 18 Hole Medal. Max h’cap 28 boys & girls 36. Entry Fee £8.00 (no cheques please) Also, 9 hole competition for Juniors not eligible for competition, £3.00 per player. Sunday 28th June – Men’s Open 18 Hole Individual Medal for Category 1 and 2. Full H’cap, Scratch and H’cap Prizes. 18 Hole Individual Stableford for Category 3 and up. Entry Fee £22.00 (members £12.00) inc ‘Stacked Hot Meat Bap’ of your choice after your round. Wednesday 22nd July - Ladies Team Open 18 Hole Team of Three Stableford. Coffee & Pastry on Arrival with Two Course Meal and Coffee. Max 36 h’cap. Please enter in Threeballs. Entry Fee - £29.00 (members £23.00) Thursday 23rd July - Seniors Individual Open Individual Stableford played in Fourballs. Maximum playing handicap 24 with full allowance. Coffee on Arrival with Two Course Carvery and Coffee after your round. Prizes inc Super Seniors Category. Entry Fee - £29.00 (members £23.00) Friday 24th July - Fourman Team Fourball Betterball Stableford with two scores to count on each hole. -

JULY 2013 EDITORIAL I Must Admit That I Had a Job Stealing Myself from the Sunshine to Write This

YOUR SUMMER Camelfordian JULY 2013 EDITORIAL I must admit that I had a job stealing myself from the sunshine to write this. I have been trying to grow my own fruit and vege- tables and have found it to be a little more complicated than “shove it in the ground and wait!” My dog has found a cool place to lie in my first ever attempt to grow strawberries and there are only four gooseberries on my prize bush. I shall look forward to harvesting my pea and broad bean in the very near future. I do seem to be very successful at perpetual spinach and lettuce but have managed to kill the mint. I find the biggest pleasure to be lying back with a gin and tonic after I have worked up a sweat and shall continue with this long after I have given up self sufficiency. Don’t forget that there is no in August so you must make this one last! WEBSITE UPDATE We launched the Camelfordian website for the announcement to appear in our June edition. It arrived a little before its time, but has been updated and hopefully improved. You can now click on the thumbnails to bring up copies of the Camel- fordian. Other hyperlinks should now work properly and there is music to accompa- ny some of the pages. It has been checked in Internet Explorer, Firefox, Opera and Google Chrome. However, if you find any problems, any issues with the Website, please let us know. Letter to the editor Dear Editor I would like, through your publication, to express my congratulations to the organisers of the “Street Party” staged on Sunday, 2nd June in Camelford. -

The Cornwall Community Land Trust Project

Delivering Homes and Assets with Communities: The Cornwall Community Land Trust Project By Tom Moore and Roger Northcott Community Finance Solutions, University of Salford 30 September 2010 Contents 3 Executive Summary 5 Background to the Cornwall Community Land Trust Project 7 Financial and Organisational Development 9 Partnering Organisations: Cornwall Rural Housing Association 11 Cornwall CLT and Local Community Land Trusts 16 Conclusion 18 List of appendices 19 Appendix 1: Cornwall Community Land Trust Project Headline Objectives 21 Appendix 2: Cornwall CLT Limited Business Plan 2008/2012. 37 Appendix 3: Blisland Community Land Trust Development Case Study 39 Appendix 4: Cornwall Council and Cornwall CLT Revolving Loan Fund Synopsis 40 Appendix 5: Project Updates: Community Land Trusts in Cornwall Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank the representatives of Cornwall CLT, Cornwall Rural Housing Association, St Just in Roseland CLT, Land’s End Peninsula CLT, St Ewe Affordable Homes Ltd, and St Minver CLT for their participation in this research. They would also like to thank the CLT Supervisory Board and management boards of Cornwall Rural Housing Association and Cornwall CLT for their constructive comments and feedback. St Minver CLT Self-Build Development, 2008. 2 Executive Summary The Cornwall Community Land Trust Project commenced in April 2006 with the aim of creating a countywide umbrella community land trust. Eight headline objectives1 were identified at the outset of the project with the overall aim of establishing a body capable of bringing forward and providing development services and opportunities to local groups across the county. This report provides a review of the Cornwall Community Land Trust Project and reflections on the experiences of the umbrella CLT since the project concluded. -

St MINVER LOWLANDS PARISH

St MINVER LOWLANDS PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE COUNCIL MEETING HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBER, ROCK METHODIST CHAPEL ON MONDAY, 7th NOVEMBER 2011 @ 7.30pm Present: Cllr. Mrs Mould (Chairman) Cllr. Blewett Cllr. Gisbourne (PC/CC) Cllr. Mrs Morgan Cllr. Rathbone Cllr. Taper Cllr. Mrs Webb Mrs Thompson (Clerk) AGENDA ITEMS Action Minute Chairman’s Welcome and Public Forum – the Chairman welcomed those present. Mr Matt Marshall, farmer of Porthilly, met with Members. He wants to convert a barn to a dwelling for his personal use and discussed the proposed plans with Members, prior to submitting a planning application. He confirmed that it will be have an occupational tie to the farm. It was thought that any problems with visibility splay could be easily remedied. Mr Tim Foster, Highways Development Management Officer was asked to attend the Meeting to discuss road safety concerns with the An Lys planning application (131d/2011 refers). He advises he has not yet seen the new application. On receipt, he will assess it and discuss any issues with the Planning Officer in due course prior to making a formal response. He is unable to meet with Members, but if the Planning Committee holds a site meeting he will endeavour to attend. 127/2011 Apologies for Absence – Cllrs. Gibson and Gilbert (both with personal commitments) and Strong (leave). 128/2011 Members’ Declarations: a. Declarations of Interest, in Accordance with the Agenda – Cllr. Mould in Clerk to 131g/2011 record b. Declarations of Gifts over £25 – none Cllr. Webb c. Register of Members’ Interests – Cllr. Webb will return her revised form. -

The Lodge Lanhydrock | Bodmin | Cornwall GUIDE £427,500

in association with The Lodge Lanhydrock | Bodmin | Cornwall GUIDE £427,500 THE LODGE LANHYDROCK GOLF CLUB· LANHYDROCK· BODMIN· CORNWALL· PL30 5AQ Having a unique location close to the first tee, this individual four bedroom home is set in large and well planned gardens of about 0.4 of an acre with an expansive outlook over the Golf Club and beyond. • Large and immaculate family home • Large kitchen, utility and cloaks /w.c. • Four bedrooms, principal en-suite and family bathroom • Large integral double garage • Located in well screened gardens adjoining the first tee • Gas fired central heating and double glazing • Two large reception rooms and study/bedroom five • In and out entrance drives LOCATION The Lodge enjoys a most appealing setting being an individual home clematis. The lawns also extend to a further screened garden ar ea adjoining the fine facilities offered by the Lanhydrock Golf Course, well enclosed for privacy with a high Cornish hedge running the Country Club and Hotel. The location of the property allows quick whole length of the rear boundary. Timber fencing is provided to access to Bodmin Parkway Station and also to the A30 and A38 other boundaries adjoining the Golf Course and have stepping trunk roads with Exeter being less than an hours drive. Nearby is stone footpaths with paving slabs, granite chippings and low s tone Lanhydrock House and gardens, maintained by the National Trust kerbs to parts. and the fine scenery surrounding to the south of Bodmin. Newquay Cornwall Airport is about half an hours drive, offering a range of air THE ACCOMMODATION flights both nationally and internationally. -

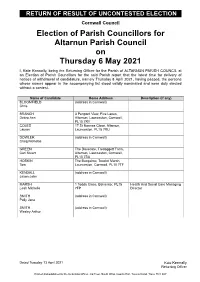

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Cornwall Parish Registers. Marriages. VIII

Co r nwall Par is h ( m arriages. ED ITE D B Y M R E . W . PH I LLI O P W . , M A , R THOMAS TAYLO , M . A . , ’ V ar . t i i c of S t j us n P enwzth . A N D H MR S . J. G LEN C ROSS . VOL . VI I I . 10110011 I S SUE D TO xm: S UB S CRIBERS BY PH I LLI MOR E Co 12 H A C Y A 4 , C N ER L NE , I 90 5 P R E F A C E . Those who have wat ch ed the patient laborious effort by whi c h only it has become possible to issue two volumes of Cornish Registers every year , will appreciate the feeling o fsatisfaction wherewith the editors again commit the results the of the of their labours into hands subscribers . I t was B o c — a rad . o r hoped th t Boconnoc , , and St Winnow som e of e —w e e the th m ould hav b en included in present volume , was e out the but , as point d in a previous issue , contents of a volume are condition ed by the amount of available e e w a e material , and it seemed b tt r to print h t was alr ady in hand than to wait until the entries of the above parishes were transcribed . Not th at subscribers hav e any reason to be disappointed with the contents of the volum e as it ff is here presented . -

5-Lanhydrock.Pdf

A4 Leaflet Tri-fold - Lanhydrock.qxp_Layout 1 29/10/2018 14:14 Page 1 VISIT ONE OF THESE WHY NOT VISIT... GREAT SPOTS Lanhydrock Hotel & Golf Club. 18 hole course, driving range, 45 bedroom > St Hydrock Church accommodation, Nineteen Bar and Bistro > Lanhydrock Golf Club serving lunch and dinner and Sunday > Respryn Woods carvery. www.lanhydrockhotel.com > Cycle Trails > Cricket Club > River Fowey > War Memorial Hall > Lanhydrock House and Gardens > Prindl Pottery YOU CAN GET MORE INFORMATION ABOUT LANHYDROCK FROM: Bodmin Information Centre Shire Hall Mount Folly Bodmin, Cornwall PL31 2DQ Tel: 01208 76616 (select option 1) Email: [email protected] ST HYDROC’S CHURCH Web: www.bodminlive.com St Hydroc’s church is the parish church for the community of Lanhydrock. The present building dates back to the 15th century, although there was a place of worship on the site prior to that. www.facebook.com/bodminvisitorcentre Services are held every Sunday using liturgy from Lanhydrock the Book of Common Prayer. The church Bodmin Information Centre is open all year round contains some fine stained glass and is open to visitors during the day when the National Trust EXPLORE THE HEART property is open. The visitors’ book is testament OF CORNWALL… THE BODMIN to the fact people find it a place where they can COMMUNITY www.bodminlive.com sit, relax and find some peace and quiet. NETWORK AREA A4 Leaflet Tri-fold - Lanhydrock.qxp_Layout 1 29/10/2018 14:14 Page 2 WELCOME TO HWITHREWGH PLUWHEDREK LANHYDROCK – EXPLORE LANHYDROCK A rural parish steeped in history located 3-4 miles to the south of Bodmin, Lanhydrock is a sparsely 1 Lanhydrock Golf Club populated rural parish which was historically 2 Lanhydrock House centred around Lanhydrock House.