The Functional Consequences of Social Distraction: Attention And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archives De Pierre Buser

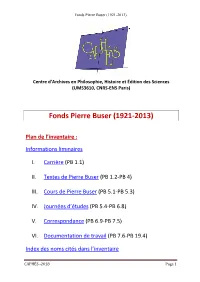

Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Centre d’Archives en Philosophie, Histoire et Édition des Sciences (UMS3610, CNRS-ENS Paris) Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Plan de l’inventaire : Informations liminaires I. Carrière (PB 1.1) II. Textes de Pierre Buser (PB 1.2-PB 4) III. Cours de Pierre Buser (PB 5.1-PB 5.3) IV. Journées d’études (PB 5.4-PB 6.8) V. Correspondance (PB 6.9-PB 7.5) VI. Documentation de travail (PB 7.6-PB 19.4) Index des noms cités dans l’inventaire CAPHÉS -2018 Page 1 Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Biographie : Notice issue du site de l’Académie des sciences Pierre Buser, né le 19 août 1921 est décédé le 29 décembre 2013. Il avait été élu correspondant de l'Académie le 4 février 1980, puis membre le 6 juin 1988 dans la section actuellement dénommée Biologie intégrative. Ancien élève de l'École normale supérieure, il était professeur émérite à l'Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie. Neurophysiologiste, il fut un des fondateurs, en France et dans le monde, de la physiologie intégrative moderne du système nerveux. Il appartenait à l'École de neurophysiologie du comportement qui poursuit ses investigations dans le champ de la psychophysiologie et des fonctions infiniment complexes du cerveau. Avec lui, c'est le maître de toute une génération de neurobiologistes qui [a disparu]. Pierre Buser a consacré ses travaux à la neurophysiologie et à la psychophysiologie. Il [a poursuivi] ses investigations dans le champ infiniment complexe des fonctions du cerveau. Les travaux de Pierre Buser se sont de façon permanente centrés autour des activités électrophysiologiques du cerveau, comme marqueurs de son activité, en liaison avec le comportement de l’animal. -

Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability

Eleventh International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic, and Social Sustainability 21–23 JANUARY 2015 | SCANDIC HOTEL COPENHAGEN COPENHAGEN, DENMARK | ONSUSTAINABILITY.COM Sustainability Conference 1 Dear Delegate, The Sustainability knowledge community is an international conference, a cross-disciplinary scholarly journal, a book imprint, and an online knowledge community which, together, set out to describe, analyze and interpret the role of Sustainability. These media are intended to provide spaces for careful, scholarly reflection and open dialogue. The bases of this endeavour are cross- disciplinary. The community is brought together by a common concern for sustainability in an holistic perspective, where environmental, cultural, economic and, social concerns intersect. In addition to organizing the Sustainability Conference, Common Ground publishes papers from the conference at http://onsustainability.com/publications/journal. We do encourage all conference participants to submit an article based on their conference presentation for peer review and possible publication in the journal. We also publish books at http://onsustainability.com/publications/books, in both print and electronic formats. We would like to invite conference participants to develop publishing proposals for original works or for edited collections of papers drawn from the journal which address an identified theme. Finally, please join our online conversation by subscribing to our monthly email newsletter, and subscribe to our Facebook, RSS, or Twitter feeds at http://onsustainability.com. Common Ground also organizes conferences and publishes journals in other areas of critical intellectual human concern, including diversity, museums, technology, humanities and the arts, to name several (see http://commongroundpublishing.com). Our aim is to create new forms of knowledge community, where people meet in person and also remain connected virtually, making the most of the potentials for access using digital media. -

Attention Modulates Maintenance of Representations in Visual Short-Term Memory

Attention Modulates Maintenance of Representations in Visual Short-term Memory Bo-Cheng Kuo, Mark G. Stokes, and Anna Christina Nobre Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/24/1/51/1780230/jocn_a_00087.pdf by MIT Libraries user on 17 May 2021 Abstract ■ Recent studies have shown that selective attention is of consid- retrospective cues during the maintenance period could predict a erable importance for encoding task-relevant items into visual specific item (spatial retrocue) or multiple items (neutral retrocue) short-term memory (VSTM) according to our behavioral goals. thatwouldbeprobedattheendofthememorydelay.Ourresults However, it is not known whether top–down attentional biases revealed that VSTM performance is significantly improved by ori- can continue to operate during the maintenance period of VSTM. enting attention to the location of a task-relevant item. The behav- We used ERPs to investigate this question across two experiments. ioral benefit was accompanied by modulation of neural activity Specifically, we tested whether orienting attention to a given spa- involved in VSTM maintenance. Spatial retrocues reduced the tial location within a VSTM representation resulted in modulation magnitude of the CDA, consistent with a reduction in memory of the contralateral delay activity (CDA), a lateralized ERP marker load. Our results provide direct evidence that top–down control of VSTM maintenance generated when participants selectively modulates neural activity associated with maintenance in VSTM, encode memory -

Dissociable Prior Influences of Signal Probability and Relevance on Visual Contrast Sensitivity

Correction PSYCHOLOGICAL AND COGNITIVE SCIENCES Correction for “Dissociable prior influences of signal probability and relevance on visual contrast sensitivity,” by Valentin Wyart, Anna Christina Nobre, and Christopher Summerfield, which appeared in issue 9, February 28, 2012, of Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (109:3593–3598; first published February 13, 2012; 10.1073/ pnas.1120118109). The authors note that on page 3597, right column, the third equation (for soft threshold nonlinearity) appeared incorrectly. The corrected equation appears below: x Γ½x ¼ x þ α − exp α www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1204601109 6354 | PNAS | April 17, 2012 | vol. 109 | no. 16 www.pnas.org Downloaded by guest on September 30, 2021 Dissociable prior influences of signal probability and relevance on visual contrast sensitivity Valentin Wyarta,1, Anna Christina Nobrea,b, and Christopher Summerfielda aDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3UD, United Kingdom; and bOxford Centre for Human Brain Activity, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Warneford Hospital, Oxford OX3 7JX, United Kingdom Edited by Ranulfo Romo, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City, DF, Mexico, and approved January 18, 2012 (received for review December 7, 2011) According to signal detection theoretical analyses, visual signals increasing the baseline activity of signal-selective units or by occurring at a cued location are detected more accurately, whereas shifting the observer’s decision criterion toward one of the two frequently occurring ones are reported more often but are not better responses. However, the binary classification of stimuli as signal- − distinguished from noise. However, conventional analyses that present (S+) and signal-absent (S ) used by conventional SDT estimate sensitivity and bias by comparing true- and false-positive analyses makes it difficult to arbitrate between these different rates offer limited insights into the mechanisms responsible for these possibilities, for a number of reasons. -

Imagining a Brighter Future the Effect of Positive Imagery Training on Mood, Prospective Mental Imagery and Emotional Bias in O

Author’s Accepted Manuscript Imagining a brighter future: The effect of positive imagery training on mood, prospective mental imagery and emotional bias in older adults Susannah E. Murphy, M. Clare O’Donoghue, Erin H.S. Drazich, Simon E. Blackwell, Anna Christina Nobre, Emily A. Holmes www.elsevier.com/locate/psychres PII: S0165-1781(15)00516-8 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.059 Reference: PSY9111 To appear in: Psychiatry Research Received date: 17 October 2014 Revised date: 3 July 2015 Accepted date: 19 July 2015 Cite this article as: Susannah E. Murphy, M. Clare O’Donoghue, Erin H.S. Drazich, Simon E. Blackwell, Anna Christina Nobre and Emily A. Holmes, Imagining a brighter future: The effect of positive imagery training on mood, prospective mental imagery and emotional bias in older adults, Psychiatry Research, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.059 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Imagining a brighter future: the effect of positive imagery training on mood, prospective mental imagery and emotional bias in older adults Susannah E. Murphya *, M. Clare O’Donoghuea, Erin H. S. Drazicha, Simon E. -

Long-Term Memories Bias Sensitivity and Target Selection in Complex Scenes

Long-term Memories Bias Sensitivity and Target Selection in Complex Scenes Eva Zita Patai1, Sonia Doallo1,2, and Anna Christina Nobre1 Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/24/12/2281/1778489/jocn_a_00294.pdf by MIT Libraries user on 17 May 2021 Abstract ■ In everyday situations, we often rely on our memories to by investigating whether and how LTM can enhance percep- find what we are looking for in our cluttered environment. Re- tual sensitivity to identify targets occurring within their com- Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jocn/article-pdf/24/12/2281/1944762/jocn_a_00294.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 cently, we developed a new experimental paradigm to investi- plex scene context. Behavioral measures showed superior 0 gate how long-term memory (LTM) can guide attention and perceptual sensitivity (d ) for targets located in remembered showed how the pre-exposure to a complex scene in which a spatial contexts. We used the N2pc ERP to test whether LTM target location had been learned facilitated the detection of modulated the process of selecting the target from its scene the transient appearance of the target at the remembered loca- context. Surprisingly, in contrast to effects of visual spatial tion[Summerfield,J.J.,Rao,A.,Garside,N.,&Nobre,A.C. cues or implicit contextual cueing, LTM for target locations Biasing perception by spatial long-term memory. The Journal significantly attenuated the N2pc potential. We propose that of Neuroscience, 31, 14952–14960, 2011; Summerfield, J. J., the mechanism by which these explicitly available LTMs Lepsien,J.,Gitelman,D.R.,Mesulam,M.M.,&Nobre,A.C. -

Orienting Attention to Locations in Perceptual Versus Mental Representations

Orienting Attention to Locations in Perceptual Versus Mental Representations A. C. Nobre1, J. T. Coull2,*, P. Maquet2, C. D. Frith2, R. Vandenberghe3,y, and M. M. Mesulam3 Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/16/3/363/1758100/089892904322926700.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Abstract & Extensive clinical and imaging research has characterized the system for directing spatial attention to locations in the the neural networks mediating the adaptive distribution of external world. We found that these two crucial aspects of spatial attention. In everyday behavior, the distribution of spatial cognition are subserved by extensively overlapping attention is guided not only by extrapersonal targets but also by networks. However, we also found that a region of right parietal mental representations of their spatial layout. We used event- cortex selectively participated in orienting attention to the related functional magnetic resonance imaging to identify the extrapersonal space, whereas several frontal lobe regions neural system involved in directing attention to locations in selectively participated in orienting attention within on-line arrays held as mental representations, and to compare it with mental representations. & INTRODUCTION working memory, the function that mediates the on-line Attention biases the selection of targets according to maintenance and manipulation of mental representa- changing motivation and volition to guide perception tions for guiding behavior. and action. To date, the extensive research on attention Attentional orienting and working memory are sub- has focused on the selection of items located in the served by partially overlapping distributed neural sys- extrapersonal world. However, as humans, much of our tems. Spatial orienting to external events is coordinated world is internal. -

Cognitive Training in the Elderly: Bottlenecks and New Avenues

Cognitive Training in the Elderly: Bottlenecks and New Avenues Nahid Zokaei, Christopher MacKellar, GiedrėČepukaitytė, Eva Zita Patai, and Anna Christina Nobre Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/29/9/1473/1786573/jocn_a_01080.pdf by MIT Libraries user on 17 May 2021 Abstract ■ Development of measures to preserve cognitive function or lack of consensus on a comprehensive assessment protocol. We even reverse cognitive decline in the ever-growing elderly pop- propose that the success of training-based therapeutics will rely Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jocn/article-pdf/29/9/1473/1952866/jocn_a_01080.pdf by guest on 01 October 2021 ulation is the focus of many research and commercial efforts. on targeting specific cognitive functions, informed by compre- One such measure gaining in popularity is the development hensive and sensitive batteries that can provide a “fingerprint” of computer-based interventions that “exercise” cognitive func- of an individual’s abilities. Instead of expecting a panacea from tions. Computer-based cognitive training has the potential to be training regimens, focused and personalized training interven- specific and flexible, accommodates feedback, and is highly ac- tions that accommodate individual differences should be cessible. As in most budding fields, there are still considerable developed to redress specific patterns of deficits in cognitive inconsistencies across methodologies and results, as well as a rehabilitation, both in healthy aging and in disease. ■ INTRODUCTION population is therefore a primary focus of research Over the last century, the fields of medicine and health efforts. care have had tremendous success, increasing life expec- In the last decade, interest has been growing for devel- tancy to an average age of approximately 80 years (www. -

Time and the Brain: How Subjective Time Relates to Neural Time

The Journal of Neuroscience, November 9, 2005 • 25(45):10369–10371 • 10369 Mini-Symposium Time and the Brain: How Subjective Time Relates to Neural Time David M. Eagleman,1 Peter U. Tse,2 Dean Buonomano,3 Peter Janssen,4 Anna Christina Nobre,5 and Alex O. Holcombe6 1Neurobiology and Anatomy, University of Texas–Houston, Houston, Texas 77030, 2Physiological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 03755, 3Department of Neurobiology, University of California, Los Angeles Brain Research Institute, Los Angeles, California 90095, 4Laboratorium voor Neuro-en Psychofysiologie, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium, 5Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 2JD, United Kingdom, and 6School of Psychology, Cardiff University, CF10 3XQ Wales, United Kingdom Most of the actions our brains perform on a daily basis, such as perceiving, speaking, and driving a car, require timing on the scale of tens to hundreds of milliseconds. New discoveries in psychophysics, electrophysiology, imaging, and computational modeling are contribut- ing to an emerging picture of how the brain processes, learns, and perceives time. Key words: brain; time; behavior; perception; psychophysics; illusion; causality Brains have a difficult problem to solve. Signals from different Psychophysics modalities are processed at different speeds in distant neural re- Much of what we know about time in the brain comes from gions, but to be useful to the organism as a whole, these signals psychophysical experiments. One class of studies involves ways in must become aligned in time and correctly tagged to outside which time perception distorts: for example, during brief, dan- events (Eagleman, 2005b). Understanding the timing of events, gerous events, such as car accidents and robberies, many people such as a motor act followed by a sensory consequence, is critical report that events pass in slow motion as if time slowed down. -

Age-Related Changes in Visual Attention Capacity and the Impact of Cognitive Training

Age-related changes in visual attention capacity and the impact of cognitive training Melanie Daniela Penning Dissertation der Graduate School of Systemic Neurosciences der Ludwig Maximilians Universität München ‐ 23.05.2019‐ Supervisor PD Dr. Kathrin Finke Department Psychology General and Experimental Psychology Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München First Reviewer: PD Dr. Kathrin Finke Second Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Hermann J. Müller External Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Anna Christina Nobre Date of Defense: 20.11.2019 Acknowledgments Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Kathrin Finke for allowing me to work on topics I am passionate about and giving me guidance and support along the way. Many thanks go to her and my TAC members Hermann Müller and Christian Sorg for their valuable advice, helpful contributions and numerous illuminating discussions. Furthermore, I would like to thank Petra Redel for helping me in getting started in the area of cognitive training and sharing her knowledge and experience with me. Special thanks go also to all other co-authors I have been working with, especially to my shared first co-authors Erika Künstler and Adriana Ruiz-Rizzo, and to Peter Bublak, who served as shared senior author on one of the manuscripts of this thesis. Furthermore, I would like to thank Maria Fernanda Urquijo Castro and Alyssa Torske for taking over several training sessions. My thanks go also to Florian Pargent for his helpful comments on this thesis. The GSN provided me with a stimulating and motivating (and also fun) environment, and for that I am deeply grateful. My thanks go to the whole GSN team for their patience and constant willingness to help. -

The Timing of Neural Activity During Shifts of Spatial Attention

The Timing of Neural Activity during Shifts of Spatial Attention Debora Brignani1,Jo¨ran Lepsien2*, Matthew F. S. Rushworth2, and Anna Christina Nobre2 Downloaded from http://mitprc.silverchair.com/jocn/article-pdf/21/12/2369/1759871/jocn.2008.21176.pdf by guest on 18 May 2021 Abstract & We developed a new experimental task to investigate the cues. Another behavioral experiment showed that overt shifts relative timing of neural activity during shifts of spatial atten- of spatial attention were mainly complete by around 400 msec, tion with event-related potentials. The task enabled the inves- placing an upper boundary for isolating neural activity that was tigation of nonlateralized as well as lateralized neural activity instrumental in controlling spatial shifts. Event-related poten- associated with spatial shifts. Participants detected target tials recorded during a covert version of the focused-attention stimuli within one of two peripheral streams of visual letters. task showed a large amount of nonlateralized neural activity Colored letters embedded within the streams indicated which associated with spatial shifts, with significant effects starting stream was to be used for target detection, signaling that par- around 330 msec. The effects started over posterior scalp re- ticipants should ‘‘hold’’ or ‘‘shift’’ their current focus of spa- gions, where they remained pronounced. Transient effects were tial attention. A behavioral experiment comparing performance also observed over frontal scalp regions. The results are com- in these focused-attention conditions with performance in a patible with a pivotal role of posterior parietal areas in initiating divided-attention condition confirmed the efficacy of the spatial shifts of spatial attention. -

CHANGES in AFFECTIVE WORKING MEMORY in AGING Changing Interpretations of Emotional Expressions in Working Memory W

Running head: CHANGES IN AFFECTIVE WORKING MEMORY IN AGING 1 Changing interpretations of emotional expressions in working memory with aging Robert M. Mok1,2, Jasper E. Hajonides van der Meulen1,2, Emily A. Holmes3, Anna Christina Nobre1,2 1Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford 2Oxford Centre for Human Brain Activity, Department of Psychiatry, Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, University of Oxford 3Department for Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Author note This study was supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (ACN) 104571/Z/14/Z, an European Union FP7 Marie Curie ITN Grant N. 606901 (INDIREA), the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre, and the NIHR Oxford cognitive health CRF. The Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging is supported by core funding from the Wellcome Trust (203139/Z/16/Z). Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Anna Christina Nobre, Oxford Centre for Human Brain Activity, Department of Psychiatry, Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, University of Oxford. Email: [email protected] Running head: CHANGES IN AFFECTIVE WORKING MEMORY IN AGING 2 Abstract Working memory (WM) shows significant decline with age. Interestingly, some research has suggested that age-related impairments can be reduced in tasks that involve emotion-laden stimuli. However, only a few studies have explored how WM for emotional material changes in aging. Here we developed a novel experimental task to compare and contrast how emotional material is represented in older versus younger adults. The task enabled us to separate overall WM accuracy from emotional biases in the content of affective representations in WM.