As in Email Sent Previously, I Could Use Any of the Official Goggle Box

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities As Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field

Celebrities as Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field Ellen Watts Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics 2018 Declaration I, Ellen Watts, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Ellen Watts September 17, 2018. 2 Abstract The ability of celebrities to become influential political actors is evident (Marsh et al., 2010; Street 2004; 2012, West and Orman, 2003; Wheeler, 2013); the process enabling this is not. While Driessens’ (2013) concept of celebrity capital provides a starting point, it remains unclear how celebrity capital is exchanged for political capital. Returning to Street’s (2004) argument that celebrities claim to speak for others provides an opportunity to address this. In this thesis I argue successful exchange is contingent on acceptance of such claims, and contribute an original model for understanding this process. I explore the implicit interconnections between Saward’s (2010) theory of representative claims, and Bourdieu’s (1991) work on political capital and the political field. On this basis, I argue celebrity capital has greater explanatory power in political contexts when fused with Saward’s theory of representative claims. Three qualitative case studies provide demonstrations of this process at work. Contributing to work on how celebrities are evaluated within political and cultural hierarchies (Inthorn and Street, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Mendick et al., 2018; Ribke, 2015; Skeggs and Wood, 2011), I ask which key factors influence this process. -

MUHAMMAD ALI Celebrating the Life of a Boxing Legend and Activist

DUVET DAYS: The top ten excuses for calling in sick in Britain Photo Credit: PA Images FOOD FOR THOUGHT All you need to know about staying healthy MUHAMMAD ALI Celebrating the life of a boxing legend and activist Vision StanmoreEdgware | Edition 3 | July 2016 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 V1 Buy - Rent - Sell - Let PARKERS For a FREE no obligation, sales or lettings valuation please contact your nearest office Stanmore Office: Bushey Office: Tel: 020 8954 8244 Tel: 020 8950 5777 83 Uxbridge Road, Stanmore, HA7 3NH 63 High Road, Bushey, WD23 1EE V2 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 V3 100 95 75 25 5 0 ParkersFeb14 13 February 2014 15:17:39 6 HISTORY V Editor’s 11 FOOD & DRINK CONTENTS 14 FASHION notes... 15 BEAUTY Hello and welcome to the third 18 HOLLY WILLOUGHBY edition of VISION Stanmore & Edgware lifestyle magazine. 19 TRAVEL The magazine is really starting to take off now, 21 KIDS with lots of suggestions from readers and more 22 CAROLINE AHERNE Misha Mistry, Design Editor exciting content to bring you this month. 23 LOCAL NEWS Despite the frequent rain showers, the summer holidays are finally here, so we have everything you need to survive 32 JOANNA LUMLEY the next six weeks…from fun family activities, to top tips to survive those long train, plane or car journeys with 35 BUSINESS & FINANCE the kids. Mum of three, Holly Willoughby even shares her wisdom, following the release of her own parenting book. 40 GARDENING We pay tribute to ‘The Greatest’, Muhammad Ali, and relive his most talked about moments, alongside the 41 MUHAMMAD ALI impression he left on the world. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

The Salopian No

TITLE HERE 1 THE SALOPIAN SALOPIAN CLUB FORTHCOMING EVENTS n More details can be found on the Salopian Club website: www.shrewsbury.org.uk/page/os-events THE SALOPIAN Issue No. 159 - Winter 2016 n Sporting fixtures at: www.shrewsbury.org.uk/page/os-sport (Click on individual sport) n Except where stated email: [email protected] All Shrewsbury School parents (including former parents) and guests of members are most welcome at the majority of our events. It is our policy to include in all invitations all former parents for whom we have contact details. The exception is any event marked ‘Old Salopian’ which, for reasons of space, is restricted to Club members only (e.g. Birmingham Dinner). Supporters or guests are always very welcome at Salopian Club sporting or arts events. Emails containing further details are sent out prior to all events, so please make sure that we have your up to date contact details. Date Event Venue Wednesday 11 January, 7pm A Celebration of Epiphany Service St Mary-le-Bow, London WC2V 6AU led by Revd Gavin Williams (former Shrewsbury School Chaplain) with a choir conducted by OS Patrick Craig and Richard Eteson Wednesday 18 January, 5.30pm Salopian Club Committee Meeting London Thursday 2 February, 7.30pm Shrewsbury School in Concert with Barber Institute of Fine Arts a pre-concert drinks reception in the Birmingham B15 2TS Gallery at the Barber Institute Contact: [email protected] from 6-7pm Wednesday 22 February, 6.00pm OS Sports Committee Meeting London Thursday 23 February, 5.00pm Evensong at -

2020 Aacta Awards Documentary Or Factual Program Handbook

2020 AACTA AWARDS DOCUMENTARY OR FACTUAL PROGRAM HANDBOOK Contents Ambulance Australia .............................................................................................................................. 3 Australia's Ocean Odyssey: A journey down the East Australian Current ........................................... 5 Bear Koala Hero ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Big Weather (and how to survive it) ...................................................................................................... 9 Debi Marshall Investigates: Frozen Lies .............................................................................................. 11 Family Rules .......................................................................................................................................... 13 Fight for Planet A: Our Climate Challenge ........................................................................................... 15 Filthy Rich & Homeless ......................................................................................................................... 17 Guy Sebastian - The Man The Music ................................................................................................... 19 Lindy Chamberlain: The True Story ..................................................................................................... 20 Maralinga Tjarutja ............................................................................................................................... -

Mail on Sunday Reveals 999 Operators Are Ordering the Public To

Cookie Policy Feedback Monday, Mar 19th 2018 12AM -1°C 3AM -1°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest Headlines Health Health Directory Discounts Login 'Why won't they let the dead rest?' Mail Site Web Enter your search on Sunday reveals 999 operators are Advertisement ordering the public to resuscitate the dead bodies of loved ones who can't be saved for fear of 'getting in trouble' Call staff routinely ordering grieving relatives to perform CPR on dead bodies Families being 'guilt tripped' by handlers who say they'll get into trouble Doctors now demanding urgent overhaul of 999 services following MoS exposé By LOIS ROGERS FOR THE MAIL ON SUNDAY PUBLISHED: 22:00, 23 September 2017 | UPDATED: 00:00, 24 September 2017 233 257 shares View comments Emergency call handlers are routinely issuing ‘grotesque’ instructions ordering callers to attempt to resuscitate the bodies of loved ones who are obviously beyond help, The Mail on Sunday can reveal. In horrific accounts given to this newspaper, readers have told how they were commanded to perform futile chest compressions on corpses already blackened with decomposition, stiff with rigor mortis or badly damaged. Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Some told how operators ‘shouted’ at Follow Follow them, despite protestations that a @DailyMail Daily Mail parent, spouse or other family member Follow Follow had ‘been dead for hours’. @MailOnline Daily Mail Others were told they would ‘get into DON'T MISS trouble’ if they did not comply with EXCLUSIVE: Ant instructions, and they spoke of how they McPartlin emerges from were made to feel ‘guilty’ for not doing the wreck of his £26,000 Mini - SECONDS after Mini - SECONDS after enough if they objected to carrying out crashing' as Saturday CPR attempts. -

BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey Bbc One Autumn 2006.Qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3

bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:03 Page 1 BBC ONE AUTUMN 2006 Designed by Jamie Currey bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:05 Page 3 BBC ONE CONTENTS AUTUMN P.01 DRAMA P. 19 FACTUAL 2006 P.31 COMEDY P.45 ENTERTAINMENT bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 5 DRAMA AUTUMN 2006 1 2 bbc_one_autumn_2006.qxd 17/7/06 13:06 Page 7 JANE EYRE Ruth Wilson, as Jane Eyre, and Toby Stephens, as Edward Rochester, lead a stellar cast in a compelling new adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s much-loved novel Jane Eyre. Orphaned at a young age, Jane is placed in the care of her wealthy aunt Mrs Reed, who neglects her in favour of her own three spoiled children. Jane is branded a liar, and Mrs Reed sends her to the grim and joyless Lowood School where she stays until she is 19. Determined to make the best of her life, Jane takes a position as a governess at Thornfield Hall, the home of the alluring and unpredictable Edward Rochester. It is here that Jane’s journey into the world, and as a woman, begins. Writer Sandy Welch (North And South, Magnificent Seven), producer Diederick Santer (Shakespeare Retold – Much Ado About Nothing) and director Susanna White (Bleak House) join forces to bring this ever-popular tale of passion, colour, madness and gothic horror to BBC One. Producer Diederick Santer says: “Sandy’s brand-new adaptation brings to life Jane’s inner world with beauty, humour and, at times, great sadness. We hope that her original take on the story will be enjoyed as much by long- term fans of the book as by those who have never read it.” The serial also stars Francesca Annis as Lady Ingram, Christina Cole as Blanche Ingram, Lorraine Ashbourne as Mrs Fairfax, Pam Ferris as Grace Poole and Tara Fitzgerald as Mrs Reed. -

Gogglebox/Gogglesprogs Studio Lambert/ Studio Gogglebox/Gogglesprogs Channel 4

Gogglebox/Gogglesprogs Studio Lambert/ Studio Gogglebox/Gogglesprogs Channel 4 that portrayed kitchen sink drama with In two linked articles, Emma Calway explores the enduring nitty-gritty realism, albeit it in a safe popularity of Gogglebox with its audiences, while Matt environment. We can check our own Kaufman considers what Gogglebox and Gogglesprogs can thoughts, fears and hopes against a teach us about the slippery concept of postmodernism. safe paradigm, where we can judge others but don’t get judged ourselves. In this respect, we hold the power. ogglebox features a concept This safety net is structured around that could only have been a familiar recurring cast who we get realised in the 21st century, a to know over time; families, couples cross between an Orwellian and friends from all over the UK watch Gnightmare and a real version of The British TV that spans all genres. We can Royle Family (the late Caroline Aherne, watch them watching it, comfortable screenwriter and actress from the in the fact that what we see won’t be sitcom, first provided the tongue-in- gruesome or shocking. We are screened cheek narration for Gogglebox, followed from shocking content, aware of the by her co-star Craig Cash). This series cast’s reaction before we see the gets us watching other viewers on actual scene in question, providing us their own sofas in their own living with a protective prism but also with rooms, who watch the same TV that a useful way to get the lowdown on we will have watched that week. Is it, the week’s TV. -

Mark Davies Editor

Mark Davies Editor Agents Alice Dunne Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0949 Flora Line [email protected] Credits Film Production Company Notes HOME ALONE 20th Century Studios / Dir: Dan Mazer 2021 Disney+ Prod: Hutch Parker, Jeremiah Samuels, Dan Wilson with Rob Delaney, Aisling Bea, Kenan Thompson THE EXCHANGE Who's On First Films Dir: Dan Mazer 2021 Prod: Simon Horsman, Jeffrey Soros, Dan Hine (with Ed Oxenbould) BORAT SUBSEQUENT Four by Two Films / Amazon Dir: Jason Woliner MOVIEFILM Prod: Sacha Baron Cohen, Monica 2020 Levinson, Anthony Hines EVERYBODY'S TALKING Warp / Film 4 / New Regency / Additonal editing ABOUT JAMIE 20th Century Studios Dir: Jonathan Butterell 2020 Prod: Barry Ryan, Mark Herbert, Peter Carlton (with Max Harwood, Lauren Patel, Richard E. Grant, Sharon Horgan, Sarah Lancashire) United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes SUPERVIZED Merlin Films Dir: Steve Barron 2019 Prods: Steve Barron & Kieran Corrigan (with Hiran Abeysekera, Elya Baskin & Tom Berenger) DORA AND THE LOST Paramount Pictures Additional editing CITY OF GOLD Dir: James Bobin Prod: Kristin Burr (with 2019 Isabela Moner, Benicio Del Toro, Michael Peña, Eva Longoria) LONDON FIELDS Muse Films / Hero Films As Consultant Editor 2015 Dir: Matthew Cullen Prods:Jordan Gertner & Chris Hanley (with Billy Bob Thornton, Amber Heard and Johnny Depp) MAY THE BEST MAN What If It Barks Dir:Andrew O’Connor WIN Films/MGM/Orion Pictures Prods:Lee Hupfield, Ray Marshall, 2014 Andrew O'Connor and Matthew Robinson (with Rosa Salazar, Whitmer Thomas and Drew Tarver) **Official Selection SXSW Film Festival Austin Tx** ALAN PARTRIDGE: Baby Cow Films Additional editing ALPHA PAPA Dir: Declan Lowney 2013 Prods: Kevin Loader and Henry Normal (with Steve Coogan, Nigel Lindsay, Colm Meaney and Karl Theobald) Television Production Company Notes MAN VS. -

GEITF Programme 2010.Pdf

MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television Festival 27–29 August 2010 Programme of Events ON TV Contents Welcome to Edinburgh 02 Schedule at a Glance 28 Social Events 06 Friday Sessions 20 Friday Night Opening Reception / Saturday Meet Highlights include: TV’s Got to Dance / This is England and Greet / Saturday Night Party / Channel of the ‘86 plus Q&A / The Richard Dunn Memorial Lecture: Year Awards Jimmy Mulville / The James MacTaggart Memorial Lecture: Mark Thompson Sponsors 08 Saturday Sessions 30 Information 13 Extras 14 Workshops 16 EICC Orientation Guide 18 Highlights include: 50 Years of Coronation Street: A Masterclass / The Alternative MacTaggart: Paul Abbott / Venues 19 The Futureview: Sandy Climan / EastEnders at 25: A Masterclass The Network 44 Sunday Sessions 40 Fast Track 46 Executive Committee 54 Advisory Committee 55 Festival Team 56 Highlights include: Doctor Who: A Masterclass / Katie Price: Shrink Rap / The Last Laugh Keynote Speaker Biographies 52 Mark Thompson / Paul Abbott / Jimmy Mulville / Sandy Climan Welcome to Edinburgh man they call “Hollywood’s Mr 3D” Sandy Climan bacon sarnies. The whole extravaganza will be for this year's Futureview keynote to answer the hosted by Mark Austin who will welcome guests DEFINING question Will it Go Beyond Football, Films and onto his own Sunday morning sofa. Michael Grade F****ng?. In a new tie-up between the TV Festival will give us his perspective on life in his first public and the Edinburgh Interactive Festival we’ve appearance since leaving ITV. Steven Moffat will THE YEAR’S brought together the brightest brains from the be in conversation in a Doctor Who Masterclass. -

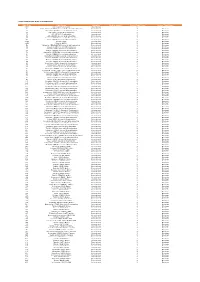

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

British Cult Comedy.Indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 Pm Cult Comedy Club up the Creek in Greenwich, Southeast London

Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain British Cult Comedy.indb 215 16/8/06 12:34:16 pm Cult comedy club Up The Creek in Greenwich, southeast London British Cult Comedy.indb 216 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm Geography Lessons: comedy around Britain Comedy just wouldn’t be comedy without local roots. And that is why, in this chapter, we take you on a tour of British comedy from Cornwall to the Scottish Highlands, visiting local comedic landmarks, clubs and festivals. Comedy is prey to the same homogenizing forces Do Part, was successfully re-created in America, that have made Starbucks globally ubiquitous but Germany and Israel, suggesting that comedy that humour doesn’t travel so easily or predictably as touches, however lightly, on universal truths can cappuccino. In the past, slang, regional vocabu- be exported around the world. lary, accents and local knowledge have often A comic’s roots, cherished or spurned, are limited a comic’s appeal, explaining why such crucial to their humour. The small screen has acts as George Formby and Tommy Trinder never made it easier for contemporary acts – nota- quite transcended the north/south divide. Yet a bly Johnny Vegas, Peter Kay and Ben Elton character as localized as Alf Garnett, the charis- – to achieve national recognition while retain- matic Cockney bigot in the sitcom Till Death Us ing a regional identity. Since the 1980s, a more 217 British Cult Comedy.indb 217 16/8/06 12:34:17 pm GEOGRapHY LESSONS: COmedY arOUND brItaIN adventurous approach to sitcoms has meant that theme to British comedy, it was that, as Linda shows such as The Royle Family have had a much Smith told him: “A lot of comics come from more authentic local flavour than most of their the edge of nowhere.” Smith often argued with predecessors.