Arxiv:Math/0505004V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Right Ideals of a Ring and Sublanguages of Science

RIGHT IDEALS OF A RING AND SUBLANGUAGES OF SCIENCE Javier Arias Navarro Ph.D. In General Linguistics and Spanish Language http://www.javierarias.info/ Abstract Among Zellig Harris’s numerous contributions to linguistics his theory of the sublanguages of science probably ranks among the most underrated. However, not only has this theory led to some exhaustive and meaningful applications in the study of the grammar of immunology language and its changes over time, but it also illustrates the nature of mathematical relations between chunks or subsets of a grammar and the language as a whole. This becomes most clear when dealing with the connection between metalanguage and language, as well as when reflecting on operators. This paper tries to justify the claim that the sublanguages of science stand in a particular algebraic relation to the rest of the language they are embedded in, namely, that of right ideals in a ring. Keywords: Zellig Sabbetai Harris, Information Structure of Language, Sublanguages of Science, Ideal Numbers, Ernst Kummer, Ideals, Richard Dedekind, Ring Theory, Right Ideals, Emmy Noether, Order Theory, Marshall Harvey Stone. §1. Preliminary Word In recent work (Arias 2015)1 a line of research has been outlined in which the basic tenets underpinning the algebraic treatment of language are explored. The claim was there made that the concept of ideal in a ring could account for the structure of so- called sublanguages of science in a very precise way. The present text is based on that work, by exploring in some detail the consequences of such statement. §2. Introduction Zellig Harris (1909-1992) contributions to the field of linguistics were manifold and in many respects of utmost significance. -

Math 250A: Groups, Rings, and Fields. H. W. Lenstra Jr. 1. Prerequisites

Math 250A: Groups, rings, and fields. H. W. Lenstra jr. 1. Prerequisites This section consists of an enumeration of terms from elementary set theory and algebra. You are supposed to be familiar with their definitions and basic properties. Set theory. Sets, subsets, the empty set , operations on sets (union, intersection, ; product), maps, composition of maps, injective maps, surjective maps, bijective maps, the identity map 1X of a set X, inverses of maps. Relations, equivalence relations, equivalence classes, partial and total orderings, the cardinality #X of a set X. The principle of math- ematical induction. Zorn's lemma will be assumed in a number of exercises. Later in the course the terminology and a few basic results from point set topology may come in useful. Group theory. Groups, multiplicative and additive notation, the unit element 1 (or the zero element 0), abelian groups, cyclic groups, the order of a group or of an element, Fermat's little theorem, products of groups, subgroups, generators for subgroups, left cosets aH, right cosets, the coset spaces G=H and H G, the index (G : H), the theorem of n Lagrange, group homomorphisms, isomorphisms, automorphisms, normal subgroups, the factor group G=N and the canonical map G G=N, homomorphism theorems, the Jordan- ! H¨older theorem (see Exercise 1.4), the commutator subgroup [G; G], the center Z(G) (see Exercise 1.12), the group Aut G of automorphisms of G, inner automorphisms. Examples of groups: the group Sym X of permutations of a set X, the symmetric group S = Sym 1; 2; : : : ; n , cycles of permutations, even and odd permutations, the alternating n f g group A , the dihedral group D = (1 2 : : : n); (1 n 1)(2 n 2) : : : , the Klein four group n n h − − i V , the quaternion group Q = 1; i; j; ij (with ii = jj = 1, ji = ij) of order 4 8 { g − − 8, additive groups of rings, the group Gl(n; R) of invertible n n-matrices over a ring R. -

![Arxiv:Math/0310146V1 [Math.AT] 10 Oct 2003 Usinis: Question Fr Most Aut the the of Algebra”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7116/arxiv-math-0310146v1-math-at-10-oct-2003-usinis-question-fr-most-aut-the-the-of-algebra-1047116.webp)

Arxiv:Math/0310146V1 [Math.AT] 10 Oct 2003 Usinis: Question Fr Most Aut the the of Algebra”

MORITA THEORY IN ABELIAN, DERIVED AND STABLE MODEL CATEGORIES STEFAN SCHWEDE These notes are based on lectures given at the Workshop on Structured ring spectra and their applications. This workshop took place January 21-25, 2002, at the University of Glasgow and was organized by Andy Baker and Birgit Richter. Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Morita theory in abelian categories 2 3. Morita theory in derived categories 6 3.1. The derived category 6 3.2. Derived equivalences after Rickard and Keller 14 3.3. Examples 19 4. Morita theory in stable model categories 21 4.1. Stable model categories 22 4.2. Symmetric ring and module spectra 25 4.3. Characterizing module categories over ring spectra 32 4.4. Morita context for ring spectra 35 4.5. Examples 38 References 42 1. Introduction The paper [Mo58] by Kiiti Morita seems to be the first systematic study of equivalences between module categories. Morita treats both contravariant equivalences (which he calls arXiv:math/0310146v1 [math.AT] 10 Oct 2003 dualities of module categories) and covariant equivalences (which he calls isomorphisms of module categories) and shows that they always arise from suitable bimodules, either via contravariant hom functors (for ‘dualities’) or via covariant hom functors and tensor products (for ‘isomorphisms’). The term ‘Morita theory’ is now used for results concerning equivalences of various kinds of module categories. The authors of the obituary article [AGH] consider Morita’s theorem “probably one of the most frequently used single results in modern algebra”. In this survey article, we focus on the covariant form of Morita theory, so our basic question is: When do two ‘rings’ have ‘equivalent’ module categories ? We discuss this question in different contexts: • (Classical) When are the module categories of two rings equivalent as categories ? Date: February 1, 2008. -

Geometries Over Finite Rings

Innovations in Incidence Geometry Volume 15 (2017), Pages 123–143 ISSN 1781-6475 50 years of Finite Geometry, the “Geometries over finite rings” part Dedicated to Prof. J.A. Thas on the occasion of his 70th birthday Dirk Keppens Abstract Whereas for a substantial part, “Finite Geometry” during the past 50 years has focussed on geometries over finite fields, geometries over finite rings that are not division rings have got less attention. Nevertheless, sev- eral important classes of finite rings give rise to interesting geometries. In this paper we bring together some results, scattered over the litera- ture, concerning finite rings and plane projective geometry over such rings. The paper does not contain new material, but by collecting information in one place, we hope to stimulate further research in this area for at least another 50 years of Finite Geometry. Keywords: ring geometry, finite geometry, finite ring, projective plane MSC 2010: 51C05,51E26,13M05,16P10,16Y30,16Y60 1 Introduction Geometries over rings that are not division rings have been studied for a long time. The first systematic study was done by Dan Barbilian [11], besides a mathematician also one of the greatest Romanian poets (with pseudonym Ion Barbu). He introduced plane projective geometries over a class of associative rings with unit, called Z-rings (abbreviation for Zweiseitig singulare¨ Ringe) which today are also known as Dedekind-finite rings. These are rings with the property that ab = 1 implies ba = 1 and they include of course all commutative rings but also all finite rings (even non-commutative). Wilhelm Klingenberg introduced in [52] projective planes and 3-spaces over local rings. -

Symmetry on Rings of Differential Operators

Symmetry on rings of differential operators Eamon Quinlan-Gallego ∗ September 17, 2021 Abstract If k is a field and R is a commutative k-algebra, we explore the question of when the ring DRSk of k-linear differential operators on R is isomorphic to its opposite ring. Under mild hypotheses, we prove this is the case whenever R Gorenstein local or when R is a ring of invariants. As a key step in the proof we show that in many cases of interest canonical modules admit right D-module structures. 1 Introduction Let k be a field. A construction of Grothendieck assigns to every k-algebra R its ring DRSk of k-linear differential operators, which is a noncommutative ring that consists of certain k-linear operators on R [Gro65, §16]. Suppose k has characteristic zero. If R ∶= k x1,...,xn is a polynomial ring over k then the ring DRSk is called the Weyl algebra over k and it has a particularly[ ] pleasant structure; for example, it is (left and right) Noetherian and its global dimension is n [Roo72]. These facts adapt readily to the case where R is an arbitrary regular k-algebra that is essentially of finite type [Bj¨o79, §3], and in this context the study of DRSk and its modules has numerous applications in singularity theory (e.g. Bernstein-Sato polynomials) and in commutative algebra (e.g. the study of local cohomology [Lyu93]). Since the ring DRSk is noncommutative, a priori its left and right modules could behave very differently. op However, a key feature of the Weyl algebra DRSk is that it is isomorphic to its opposite ring DRSk via an involutive isomorphism that fixes the subring R (see Remark 2.6). -

Chapter I: Groups 1 Semigroups and Monoids

Chapter I: Groups 1 Semigroups and Monoids 1.1 Definition Let S be a set. (a) A binary operation on S is a map b : S × S ! S. Usually, b(x; y) is abbreviated by xy, x · y, x ∗ y, x • y, x ◦ y, x + y, etc. (b) Let (x; y) 7! x ∗ y be a binary operation on S. (i) ∗ is called associative, if (x ∗ y) ∗ z = x ∗ (y ∗ z) for all x; y; z 2 S. (ii) ∗ is called commutative, if x ∗ y = y ∗ x for all x; y 2 S. (iii) An element e 2 S is called a left (resp. right) identity, if e ∗ x = x (resp. x ∗ e = x) for all x 2 S. It is called an identity element if it is a left and right identity. (c) The set S together with a binary operation ∗ is called a semigroup if ∗ is associative. A semigroup (S; ∗) is called a monoid if it has an identity element. 1.2 Examples (a) Addition (resp. multiplication) on N0 = f0; 1; 2;:::g is a binary operation which is associative and commutative. The element 0 (resp. 1) is an identity element. Hence (N0; +) and (N0; ·) are commutative monoids. N := f1; 2;:::g together with addition is a commutative semigroup, but not a monoid. (N; ·) is a commutative monoid. (b) Let X be a set and denote by P(X) the set of its subsets (its power set). Then, (P(X); [) and (P(X); \) are commutative monoids with respective identities ; and X. (c) x∗y := (x+y)=2 defines a binary operation on Q which is commutative but not associative. -

There Is No Analog of the Transpose Map for Infinite Matrices

Publicacions Matem`atiques, Vol 41 (1997), 653–657. THERE IS NO ANALOG OF THE TRANSPOSE MAP FOR INFINITE MATRICES Juan Jacobo Simon´ ∗ Abstract In this note we show that there are no ring anti-isomorphism be- tween row finite matrix rings. As a consequence we show that rowfinite and column finite matrix rings cannot be either iso- morphic or Morita equivalent rings. We also showthat anti- isomorphisms between endomorphism rings of infinitely generated projective modules may exist. 1. Introduction and notation The motivation for this note was to find out the extent to which the transpose for infinite matrices behaves like that for finite matrices. It is well-known that for any commutative ring, R, the transpose map t : Mn(R) → Mn(R) is an anti-automorphism. For infinite matrix rings the analogous transpose map yields an anti-isomorphism t : RFMA(R) → CFMA(R), where RFMA(R) (resp. CFMA(R)) denotes the ring of row-finite (resp. column-finite) matrices, indexed by the set A, having entries in R. Unlike the finite case, this is obviously not an anti-AUTOmorphism of RFMA(R). Thus we are led to ask: for a commutative ring, R, does there ex- ist an anti-automorphism of RFMA(R)? We answer this question in the negative, with a vengeance. In fact, we show in Theorem 2.2 that (A) there are no anti-isomorphisms between rings of the form End(RR ) (B) and End(SS ) for any rings R and S (commutative or not), and any infinite sets A and B. As a corollary we show that for any two rings R and S the rings RFMA(R) and CFMB(S) cannot be either isomorphic or Morita equivalent rings. -

Noncommutative Curves and Noncommutative Surfaces

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 38, Number 2, Pages 171{216 S 0273-0979(01)00894-1 Article electronically published on January 9, 2001 NONCOMMUTATIVE CURVES AND NONCOMMUTATIVE SURFACES J. T. STAFFORD AND M. VAN DEN BERGH Abstract. In this survey article we describe some geometric results in the theory of noncommutative rings and, more generally, in the theory of abelian categories. Roughly speaking and by analogy with the commutative situation, the cat- egory of graded modules modulo torsion over a noncommutative graded ring of quadratic, respectively cubic, growth should be thought of as the noncom- mutative analogue of a projective curve, respectively surface. This intuition has led to a remarkable number of nontrivial insights and results in noncom- mutative algebra. Indeed, the problem of classifying noncommutative curves (and noncommutative graded rings of quadratic growth) can be regarded as settled. Despite the fact that no classification of noncommutative surfaces is in sight, a rich body of nontrivial examples and techniques, including blowing up and down, has been developed. Contents 1. Introduction 172 2. Geometric constructions 177 3. Twisted homogeneous coordinate rings 180 4. Algebras with linear growth 182 5. Noncommutative projective curves I: Domains of quadratic growth 183 6. Noncommutative projective curves II: Prime rings 186 7. Noncommutative smooth proper curves 189 8. Artin-Schelter regular algebras 194 9. Commutative surfaces 198 10. Noncommutative surfaces 200 11. Noncommutative projective planes and quadrics 202 12. P1-Bundles 206 13. Noncommutative blowing up 208 Index 213 References 213 Received by the editors October 18, 1999, and in revised form May 20, 2000. -

Bimodules and Abelian Surfaces ∗

Bimodules and Abelian Surfaces ∗ Kenneth A. Ribet† To Professor K. Iwasawa Introduction In a manuscript on mod ` representations attached to modular forms [26], the author introduced an exact sequence relating the mod p reduction of certain Shimura curves and the mod q reduction of corresponding classical modular curves. Here p and q are distinct primes. More precisely, fix a maximal order O in a quaternion algebra of discriminant pq over Q. Let M be a positive integer prime to pq. Let C be the Shimura curve which classifies abelian surfaces with an action of O, together with a “Γo(M)-structure.” Let X be the standard modular curve Xo(Mpq). These two curves are, by definition, coarse moduli schemes and are most familiar as curves over Q (see, for example, [28], Th. 9.6). However, they exist as schemes over Z: see [4, 6] for C and [5, 13] for X . In particular, the reductions CFp and XFq of C and X , in characteristics p and q respectively, are known to be complete curves whose only singular points are ordinary double points. In both cases, the sets of singular points may be calculated in terms of the arithmetic of “the” rational quaternion algebra which is ramified precisely at q and ∞. (There is one such quater- nion algebra up to isomorphism.) In [26], the author observed that these calculations lead to the “same answer” and concluded that there is a 1-1 correspondence between the two sets of singular points. He went on to re- late the arithmetic of the Jacobians of the two curves X and C (cf. -

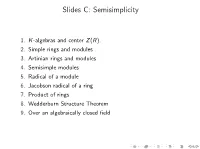

Slides C: Semisimplicity

Slides C: Semisimplicity 1. K-algebras and center Z(R). 2. Simple rings and modules 3. Artinian rings and modules 4. Semisimple modules 5. Radical of a module 6. Jacobson radical of a ring 7. Product of rings 8. Wedderburn Structure Theorem 9. Over an algebraically closed field Noncommutative rings and algebras We now return to noncommutative (but associative and unital) rings. We normally take right R-modules. Then an R-module homomorphism f : M ! N satisfies: f (xr) = f (x)r which is an \associativity rule". A left R-module is the same as a right Rop-module where Rop is the opposite ring of R with order of multiplication reversed: ab in Rop is ba in R. Definition. For K a field, a K-algebra is ring A which is also a K-module (vector space over K) so that addition is K-linear and multiplication is K-bilinear. K-algebra and center Z(R) Definition. The center Z(R) of a ring R is the set of all z 2 R which commutes with all elements of R. E.g., 0; 1 2 Z(R). Z(R) := fz 2 R j rz = zr 8r 2 Rg Proposition 1.1. Z(R) is a subring of R. Proposition 1.2. For K a field, R is a K-algebra , K ⊆ Z(R) Simple rings Definition. A ring is simple if it has no nontrivial 2-sided ideals. Examples. I Fields are simple rings. I A division ring D is simple: A division ring is a ring in which every nonzero element has an inverse. -

![The Dual of a Chain Geometry Arxiv:1304.0177V1 [Math.AG] 31](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2012/the-dual-of-a-chain-geometry-arxiv-1304-0177v1-math-ag-31-3242012.webp)

The Dual of a Chain Geometry Arxiv:1304.0177V1 [Math.AG] 31

The Dual of a Chain Geometry Andrea Blunck∗ Hans Havlicek August 23, 2021 Abstract We introduce and discuss the dual of a chain geometry. Each chain geometry is canonically isomorphic to its dual. This allows us to show that there are isomorphisms of chain geometries that arise from antiisomorphisms of the underlying rings. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 51B05. Keywords: projective line, chain geometry, duality, ring, antiiso- morphism. 1 Introduction For each left module over a ring R there is the dual module. It may be considered as a right R-module or as a left module over the opposite ring R◦. A chain geometry Σ(K; R) is based upon a proper subfield K of a ring R and the left R-module R2. Observe that we do not assume that K is in the centre of R. The dual chain geometry Σ(b K; R) of Σ(K; R) is defined via the dual module of R2. Up to notation Σ(b K; R) is the same as the chain geometry Σ(K◦;R◦). There is a \canonical isomorphism" from each chain geometry onto its dual. However, in general it seems difficult to describe it explicitly for all points in terms of coordinates unless the underlying ring R has some additional properties. arXiv:1304.0177v1 [math.AG] 31 Mar 2013 We establish that each residue of a chain geometry can be identified with a residue of its dual in a natural way. However, the (algebraically defined) relation of compatibility given on the set of blocks of each residue is not always preserved under the canonical isomorphism, whence one obtains also a notion of dual compatibility. -

3. Homomorphisms

3. Homomorphisms. 3.1. Definition, some properties. If M,M ′ are representations of the quiver Q, a homomorphism f : M → M ′ is of the ′ form f = (fx)x with linear maps fx : Mx → Mx for all x ∈ Q0 such that the following diagrams for every arrow α: x → y commute fx ′ Mx −−−−→ Mx ′ Mα Mα fy ′ My −−−−→ My To repeat: one has such a diagram for every arrow α of the quiver; the vertical data on the left are part of M, those on the right are part of M ′, the horizontal maps are those which combine to form f. Of course, given a representation M, there is always the identity homomorphism ′ 1M : M → M with (1M )x the identity map of Mx. Also, for any pair M, M of represen- ′ ′ tations, there is the zero homomorphism 0: M → M (with 0x : Mx → Mx being the zero map). Examples. Consider the three representations (0 → k), (k → 0), (1k : k → k) of the quiver Q of type A2, and let us determine whether there are non-zero homomorphisms M → M ′ or not. Of course, If M = (0 → k) and M ′ = (k → 0), there cannot be a non-zero homomorphism ′ ′ f : M → M , since f = (f1,f2) and for f1 : M1 → M1 and for ′ f2 : M2 → M2 there only exist the zero maps. Now let M = (0 → k) ′ and M = (1: k → k), and look for pairs f =(f1,f2) with f1 : M1 → ′ ′ M1 and f2 : M2 → M2. For f1 the only possibility is the zero map, whereas for f2 : k → k we may try to take any scalar multiplication, say take the multiplication by c ∈ k (as a map k → k).