Conceptualizing Kant's Mereology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JENNIFER K. ULEMAN September 2018 School of Humanities

JENNIFER K. ULEMAN September 2018 School of Humanities Purchase College 735 Anderson Hill Road Purchase, NY 10577-1400 914-251-6163 (office) [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Philosophy; University of Pennsylvania, 1995. Committee: Paul Guyer, Chair; Samuel Freeman; Susan S. Meyer. B.A. Philosophy, with High Honors, minors in English and Psychology; Swarthmore College, 1987. abroad Ruprecht-Karls Universität, Heidelberg, Germany. Year of dissertation research with H.-F. Fulda, 1993-94. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany. German language and philosophy, Winter and Summer 1985. AREAS OF RESEARCH Kant and Hegel; Race; Gender; Moral/Legal/Social/Political Theory; Higher Education. ADDITIONAL TEACHING AREAS Histories of Modern and of Nineteenth-Century Philosophy; Philosophy of Photography; Objectivity and Method. ACADEMIC POSITIONS Purchase College, Purchase, NY Associate Professor, Philosophy Board of Study 2010-present Assistant Professor, Philosophy Board of Study 2004-2010 University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy 2000-2004 Barnard College, New York, NY Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy 1998–2000 John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, New York, NY Adjunct (fall) and Visiting Assistant Professor (spring), Department of Art, Music, and Philosophy 1996-97 (non-academic professional positions and related activities, 1989-98, listed page 12) Jennifer K. Uleman 2 Jenni PUBLICATIONS Book An Introduction to Kant's Moral Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2010). Selected by Choice as an Outstanding Academic Title of 2010. Refereed Journal Articles "No King and No Torture: Kant and Suicide and Law," Kantian Review 21:1, March 2016, 77-100. "External Freedom in Kant's Rechtslehre: Political, Metaphysical," Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. -

Forthcoming in the Kant Yearbook, Vol. 11 (2019) Final Draft – Please Cite the Published Version for Correct Pagination

Forthcoming in The Kant Yearbook, Vol. 11 (2019) Final Draft – Please cite the published version for correct pagination Can there be a Finite Interpretation of the Kantian Sublime? Sacha Golob (King’s College London) Abstract Kant’s account of the sublime makes frequent appeals to infinity, appeals which have been extensively criticised by commentators such as Budd and Crowther. This paper examines the costs and benefits of reconstructing the account in finitist terms. On the one hand, drawing on a detailed comparison of the first and third Critiques, I argue that the underlying logic of Kant’s position is essentially finitist. I defend the approach against longstanding objections, as well as addressing recent infinitist work by Moore and Smith. On the other hand, however, I argue that finitism faces distinctive problems of its own: whilst the resultant theory is a coherent and interesting one, it is unclear in what sense it remains an analysis of the sublime. I illustrate the worry by juxtaposing the finitist reading with analytical cubism. §1 – Introduction Kant’s account of the sublime makes frequent reference to infinity. The “intuition” of the sublime “carries with it the idea of...infinity”; apprehension “can progress to infinity” [kann…ins Unendliche gehen]; imagination “strives to progress towards infinity” [ein Bestreben zum Fortschritte ins Unendliche]; reason demands that we “think the infinite as a whole” (KU 5:255, 252, 250, 254).1 It is obvious that the infinite played a central role in Kant’s own presentation of the problem. It is less clear whether such references are 1 References are to the standard Akademie edition of Kant’s gesammelte Schriften (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1900–; abbreviated as Ak.): Anth: Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht (Ak. -

Curriculum Vitae

Dean Franklin Moyar Department of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University 276 Gilman Hall 3400 N. Charles St. Baltimore, MD 21218 [email protected] Professional Experience 2009-present: Associate Professor (with tenure), Department of Philosophy, Johns Hopkins University. 2002-2009: Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Johns Hopkins University. Areas AOS: Kant and German Idealism, Political Philosophy, Metaethics. AOC: Philosophy of Law, Philosophy of Action, 19th Century European Philosophy, Early Modern Philosophy, American Philosophy. Education 1994-2002 University of Chicago, Ph.D. June 2002. 1999-2000 Visiting Scholar, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster, Germany. 1990-1994 Duke University. B.S. Summa Cum Laude with Honors in Physics. Second major in Philosophy. Monograph Hegel’s Conscience (Oxford University Press, 2011, paperback 2014). Edited Volumes The Oxford Handbook of Hegel, Editor (forthcoming, 2017). The Routledge Companion to Nineteenth Century Philosophy, Editor (Routledge, 2010). Winner, CHOICE award, 2010. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit: A Critical Guide, Co-Editor with Michael Quante (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Journal Articles and Book Chapters “German Idealism,” Knowledge in Early Modern Philosophy, edited by Stephen Gaukroger, (forthcoming, Bloomsbury, 2017) “Die Wahrheit der mechanistischen und teleologischen Objektivität,” for a collective commentary on the Science of Logic, edited by Michael Quante and Anton Koch (forthcoming from Meiner Verlag, 2017). “Introduction” to The Oxford Handbook -

Curriculum Vitae of Kenneth F

ROGERSON 1 Curriculum Vitae of Kenneth F. Rogerson 2863 Hazel Ave. Department of Philosophy Hood River, OR Florida International University (954) 554-9785 North Miami, Florida 33181 Education: Ph.D. in philosophy: University of California, San Diego, 1981. M.A. in philosophy: University of California, San Diego, 1977. M.A. in philosophy: San Francisco State University, 1975. B.A. in philosophy/mathematics: University of Washington, 1971. Dissertation: Title: Kant's Aesthetic Theory: The Roles of Form and Expression. Committee: Henry E. Allison (chairman), Frederick A. Olafson, Robert B. Pippin. Areas of Specialization: Kant, Ethics, Political Philosophy, Aesthetics. Areas of Competence: Modern Philosophy, Topics in philosophy of language Teaching Experience: ROGERSON 2 Professor: Florida International Univ., 1998- Associate Professor: Florida International Univ., 1990-98 Assistant Professor: Florida International Univ., 1985-89 Visiting Assistant Professor: Texas A&M University, 1984-5 Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow: Rice University, 1982-4 Visiting Lecturer: Univ. of California, San Diego, 1981-2 Instructor: University of San Diego, 1980-1 Administrative Experience: Chair of the Philosophy Department Florida International Univ., 2005-2012 Director of the Humanities Program Florida International Univ., 1994-2005 Director of Liberal Studies, Biscayne Bay Campus Florida InternationalUniv.2000-2005 Associate Chair of Philosophy, Biscayne Bay Campus Florida International Univ., 1992-2005 Director of Law, Ethics, and Society Certificate Florida International Univ., 1992- Publications: >Books: The Problem of Free Harmony in Kant=s Aesthetics (2008, SUNY press) Introduction to Ethical Theory (1991, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston) Kant's Aesthetics: The Roles of Form and Expression (1986, University Press of America) >Presidential Address: ROGERSON 3 "Kant and Anti-Realism," Southwest Philosophy Review (12:1, Jan. -

PHI 516/GER 566/REL 516 Special Topics In

PHI 516/GER 566/REL 516 Special Topics in History of Phil: Knowledge & Belief in Kant, Fichte, Hegel Instructor: Andrew Chignell ([email protected]) Spring 2020, Marx 201, Th 1:30-4:20 Office: 232 1879 Hall; Office Hours: Tues 4-5:30 and by appt A seminar on Kantian epistemology and pistology (the theory of faith or acceptance). Topics include: the nature and ethics of assent (holding-for-true); the nature of knowledge; fallibilism and infallibilism about epistemic justification; cognition and spontaneity; noumenal ignorance; opinion and common sense; epistemic autonomy; and the structure of practical arguments, both pragmatic and moral. In the final weeks of the seminar we will consider how some of these themes are treated by two of Kant’s most influential successors – J.G. Fichte and G.W.F. Hegel. Along the way, we will look at some broadly Kantian efforts in contemporary epistemology by authors like Mark Schroeder and Kurt Sylvan. Assignments: 1. Short reflections: Everyone taking the course for credit is asked to submit five 1-2 page reflections. Often these will simply elaborate a question about the reading, but they can also involve criticism or constructive work. These are due on Wednesday night before class at 11.59pm, and should focus on the readings for the following day’s class. Graded on a satisfactory/unsatisfactory basis, they are worth (combined) 30% of the grade. As long as you’re doing the required reading, it shouldn’t be hard to achieve full credit for this. 2. Presentation: Ph.D. students have the opportunity (but not the obligation) to give a short presentation to the seminar. -

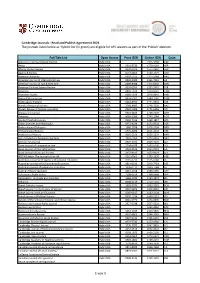

'Hybrid OA' (In Green) Are Eligible for APC Waivers As Part of the 'Publish' Element

Cambridge Journals - Read and Publish Agreement 2021 The journals listed below as 'Hybrid OA' (in green) are eligible for APC waivers as part of the 'Publish' element. Full Title List Open Access Print ISSN Online ISSN Code Advances in Archaeological Practice Hybrid OA 2326-3768 AAP Africa Hybrid OA 0001-9720 1750-0184 AFR African Studies Review Hybrid OA 0002-0206 1555-2462 ASR Ageing & Society Hybrid OA 0144-686X 1469-1779 ASO American Antiquity Hybrid OA 0002-7316 2325-5064 AAQ American Journal of International Law Hybrid OA 0002-9300 2161-7953 AJI American Journal of Law & Medicine Hybrid OA 0098-8588 2375-835X AMJ American Political Science Review Hybrid OA 0003-0554 1537-5943 PSR Americas Hybrid OA 0003-1615 1533-6247 TAM Anatolian Studies Hybrid OA 0066-1546 2048-0849 ANK Ancient Mesoamerica Hybrid OA 0956-5361 1469-1787 ATM Anglo-Saxon England Hybrid OA 0263-6751 1474-0532 ASE Annals of Actuarial Science Hybrid OA 1748-4995 1748-5002 AAS Annual Review of Applied Linguistics Hybrid OA 0267-1905 1471-6356 APL Antiquaries Journal Hybrid OA 0003-5815 1758-5309 ANT Antiquity Hybrid OA 0003-598X 1745-1744 AQY Applied Psycholinguistics Hybrid OA 0142-7164 1469-1817 APS Arabic Sciences and Philosophy Hybrid OA 0957-4239 1474-0524 ASP Archaeological Dialogues Hybrid OA 1380-2038 1478-2294 ARD Archaeological Reports Hybrid OA 0570-6084 2041-4102 ARE Architectural History Hybrid OA 0066-622X 2059-5670 ARH arq: Architectural Research Quarterly Hybrid OA 1359-1355 1474-0516 ARQ Art Libraries Journal Hybrid OA 0307-4722 2059-7525 ALJ Asian -

Dr Andrew Stephenson

CV (short) DR ANDREW STEPHENSON Trinity College Email: [email protected] Oxford OX BH Website: www.acstephenson.com AOS: KANT AOC: Mind, Epistemology, Religion, Post- Kantian Philosophy, Wittgenstein EMPLOYMENT Apr - Apr Leverhulme Research Fellow, Humboldt University, Berlin Oct - Mar Career Development Lecturer, Trinity College, Oxford EDUCATION - D.Phil. in Philosophy (cont.), University of Oxford - Leave of Absence due to serious spinal injury – fully recovered - Language Student, Stiftung Maximilianeum and LMU, Munich - D.Phil. in Philosophy, University of Oxford - B.Phil. in Philosophy, University of Oxford - B.A. in Philosophy, Cardiff University RESEARCH Articles • Kant, the Paradox of Knowability, and the Meaning of ‘Experience’, Philosophers’ Imprint (forthcoming) • Imagination and Phenomenal Character, in Kant and the Philosophy of Mind (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) • Kant on the Object-Dependence of Intuition and Hallucination, The Philosophical Quarterly () • Kant’s Deduction from Apperception?, Studi Kantiani (), - • Kant on Non-Veridical Experience, Kant Yearbook (), - Book (editor) • Kant and the Philosophy of Mind: New Essays on Consciousness, Judgement, and the Self, co-edited with Anil Gomes, Oxford University Press (forthcoming) Under Review (available from website or on request) • Kant, A Priori Knowability, and Tacit Knowledge Some Recent/Upcoming Presentations • Kant and the Logic of Knowability, Sept , International Kant Congress, Vienna • Kant’s Manifest Realism?, Sept , Colloquium -

Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D

March 2018 Scott R. Stroud - 1 - Scott R. Stroud, Ph.D. Department of Communication Studies Moody College of Communication University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX 78712-0115 [email protected] www.mediaethicsinitiative.org RESEARCH INTERESTS Communication and Culture, Communication/Media Ethics, Philosophy and Rhetoric, Religion and Rhetoric DEGREES AWARDED Ph.D. Philosophy, Temple University, 2006 M.A. Philosophy, San José State University, 2002 M.A. Communication, University of the Pacific, 2000 B.A. Communication/Philosophy, University of the Pacific, May 1998 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor (Tenured), University of Texas at Austin, Department of Communication Studies, 2014- Present. -Director, Media Ethics Initiative, University of Texas at Austin, 2016-Present. -Affiliate Faculty, University of Texas at Austin, Department of Rhetoric and Writing (2015-Present) -Affiliate Faculty, University of Texas at Austin, South Asia Institute (2017-Present) Visiting Fellow, Center for the Study of Democratic Politics, Princeton University, 2014-2015. Assistant Professor of Communication Studies (Tenure-Track), University of Texas at Austin, Department of Communication Studies, 2009-2014. Assistant Professor of Philosophy (Tenure-Track), University of Texas-Pan American, Department of History and Philosophy, 2008-2009. Lecturer (Full-time), University of Texas at Austin, Department of Communication Studies, 2006-2008. Part-Time Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Southwestern University, Department of Religion and Philosophy, Fall 2007. SCHOLARLY PUBLICATIONS Books (Refereed) Stroud, S. R. (2014). Kant and the Promise of Rhetoric, Pennsylvania State University Press, 288 pp. Reviewed in: Kantian Review (2015), Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews (2015), Advances in the History of Rhetoric (2016), Kant Studies Online (2016), International Journal of Philosophical Studies (2016), Rhetoric Review (2016), Quarterly Journal of Speech (2017), Rhetoric & Public Affairs (2017), Kant-Studien (2017). -

Kantian Review

Kantian Review Editorial policy Kantian Review publishes articles and reviews selected for their quality and relevance to current philosophical debate in relation to Kant's work. In recent times Kant's philosophy has influenced contemporary philosophers over a wide range of issues from epistemology, metaphysics and philosophy of science to moral and political philosophy, philosophy of religion, aesthetics and teleology. In these, and other, sectors Kant's views still generate debates about such issues as the character of a responsible metaphysics, epistemological scepticism, moral motivation, the foundations of politics, law and distributive justice both national and international. Kantian Review invites contributions to these debates along with original accounts of Kant's texts, and of the development of his thought in its historical background. 1. Submissions General enquiries, contributions and subsequent correspondence should be sent to the Editorial Assistant: Kantian Review Department of International Politics Aberystwyth University Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion SY23 3FE UK Email: [email protected] Electronic submissions are welcomed as email attachments in Word (.doc or .docx files). Receipt of submissions will be acknowledged. Receipt of the former will be acknowledged. The article file should be ready for blind review and must bear no trace of the author’s identity. After an initial internal review, each manuscript is generally reviewed by at least two referees, and an initial editorial decision is generally reached within 12 weeks of submission. We endeavour to provide authors with detailed feedback, but on very rare occasions this may not be possible. Submission of a paper will be taken to imply that it is unpublished and is not being considered for publication elsewhere. -

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore

Rachel Elizabeth Zuckert Department of Philosophy 5728 N. Kenmore Ave, 3N Northwestern University Chicago, IL 60660 Kresge 3-512 1880 Campus Drive home: (773) 728-7927 Evanston, IL 60208 work: (847) 491-2556 [email protected] Education: 2000 PhD, University of Chicago, Department of Philosophy and the Committee on Social Thought 1995 MA, University of Chicago, Committee on Social Thought 1992 B.A. (1), Oxford University (Philosophy and Modern Languages) 1990 B.A. (Summa Cum Laude; Highest Honors in Philosophy; Phi Beta Kappa), Williams College Areas of Specialization: Kant and eighteenth-century philosophy Aesthetics Areas of Competence: Early modern philosophy Nineteenth-century philosophy Feminist philosophy Languages: French German Academic Employment: 2018- Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2008-18 Associate Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University; affiliated with the German Department 2011-18 2006-2008 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Northwestern University 2001-2006 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Rice University 1999-2001 Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Bucknell University Zuckert 2 Publications: Books Kant on Beauty and Biology: An Interpretation of the Critique of Judgment, Cambridge University Press, 2007. Awarded the American Society for Aesthetics Monograph Prize (2008); reviewed in British Journal for the History of Philosophy, Comparative and Continental Philosophy, Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, Journal of the History of Philosophy, Metascience, Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Review of Metaphysics, and subject of review essays in Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism and Kant Yearbook Herder’s Naturalist Aesthetics, Cambridge University Press, forthcoming (2019). Edited Volume Hegel on Philosophy in History, co-edited with James Kreines, Cambridge University Press, 2017. -

Dr. Matthew C. Altman Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY

Dr. Matthew C. Altman Department of Philosophy & Religious Studies CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Publications Series (series editor) Palgrave Handbooks in German Idealism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. • Published: The Palgrave Kant Handbook (ed. M. C. Altman, 2017), The Palgrave Schopenhauer Handbook (ed. S. Shapshay, 2017). • Under contract: The Palgrave Hegel Handbook (ed. M. Bykova and K. Westphal, 2018), The Palgrave Fichte Handbook (ed. S. Hoeltzel, 2018), The Palgrave Handbook of German Romantic Philosophy (ed. E. Millán, 2018), The Palgrave Schelling Handbook (ed. S. McGrath and K. Bruff, 2018), The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Existentialism (ed. J. Stewart, 2019), The Palgrave Tillich Handbook (ed. R. Re Manning and H. Matern, 2019). • Planned: The Palgrave Handbook of Transcendental, Neo-Kantian, and Psychological Idealism; The Palgrave Handbook of Critics of Idealism; The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Analytic Philosophy; The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Phenomenology; The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism, Deconstruction, and Its Aftermath; The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Feminist Philosophy. Books (editor) The Palgrave Kant Handbook. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. (editor) The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Reviewed in: Canadian Society for Continental Philosophy, Continental Philosophy Review, Kant-Studien. (coauthor, with Cynthia D. Coe) The Fractured Self in Freud and German Philosophy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. Reviewed in: Journal of the History of Philosophy, Philosophia: International Journal of Philosophy, Philosophy in Review. (author) Kant and Applied Ethics: The Uses and Limits of Kant’s Practical Philosophy. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. Reviewed in: Choice, Diametros, Ethical Perspectives, Ethics & Behavior, Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Synthesis Philosophica. -

Kantian Review Kant on the Logical Form of Singular Judgements

Kantian Review http://journals.cambridge.org/KRV Additional services for Kantian Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Kant on the Logical Form of Singular Judgements Huaping Lu-Adler Kantian Review / Volume 19 / Issue 03 / November 2014, pp 367 - 392 DOI: 10.1017/S1369415414000168, Published online: 30 September 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S1369415414000168 How to cite this article: Huaping Lu-Adler (2014). Kant on the Logical Form of Singular Judgements. Kantian Review, 19, pp 367-392 doi:10.1017/ S1369415414000168 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/KRV, IP address: 64.134.69.88 on 01 Oct 2014 Kantian Review, 19,3,367–392 ©KantianReview, 2014 doi:10.1017/S1369415414000168 Kant on the Logical Form of Singular Judgements huaping lu-adler Georgetown University Email: [email protected] Abstract At A71/B96–7 Kant explains that singular judgements are ‘special’ because they stand to the general ones as Einheit to Unendlichkeit.Thereferenceto Einheit brings to mind the category of unity and hence raises a spectre of circularity in Kant’sexplanation.Iaimtoremovethisspectrebyinterpreting the Einheit-Unendlichkeit contrast in light of the logical distinctions among universal, particular and singular judgments shared by Kant and his logician predecessors. This interpretation has a further implication for resolving a controversy over the correlation between the logical moments of quantity (universal, particular, singular) and the categorial ones (unity, plurality, totality). Keywords: Kant, singular judgement, logical extension, unity, infinity In the Critique of Pure Reason, the basic forms of judgement are given in this 4 (titles) × 3 (moments) diagram: quantity (universal, particular, singular) quality relation (affirmative, negative, infinite) (categorical, hypothetical, disjunctive) modality (problematic, assertoric, apodictic).