Those Amazing Magnolia Fruits Richard B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Distribution and Historical Dynamics of Threatened Conifers of the Dalat Plateau, Vietnam

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM A thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By TRANG THI THU TRAN Dr. C. Mark Cowell, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM Presented by Trang Thi Thu Tran A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts of Geography And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor C. Mark Cowell Professor Cuizhen (Susan) Wang Professor Mark Morgan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research project would not have been possible without the support of many people. The author wishes to express gratitude to her supervisor, Prof. Dr. Mark Cowell who was abundantly helpful and offered invaluable assistance, support, and guidance. My heartfelt thanks also go to the members of supervisory committees, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cuizhen (Susan) Wang and Prof. Mark Morgan without their knowledge and assistance this study would not have been successful. I also wish to thank the staff of the Vietnam Initiatives Group, particularly to Prof. Joseph Hobbs, Prof. Jerry Nelson, and Sang S. Kim for their encouragement and support through the duration of my studies. I also extend thanks to the Conservation Leadership Programme (aka BP Conservation Programme) and Rufford Small Grands for their financial support for the field work. Deepest gratitude is also due to Sub-Institute of Ecology Resources and Environmental Studies (SIERES) of the Institute of Tropical Biology (ITB) Vietnam, particularly to Prof. -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

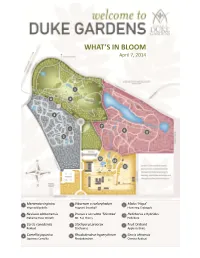

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

A Revision of Perissocarpa STEYERM. & MAGUIRE (Ochnaceae)

©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 100 B 683 - 707 Wien, Dezember 1998 A revision of Perissocarpa STEYERM. & MAGUIRE (Ochnaceae) B. Wallnöfer* With contributions by B. Kartusch (wood anatomy) and H. Halbritter (pollen morphology). Abstract The genus Perissocarpa (Ochnaceae) is revised. It comprises 3 species: P. ondox sp.n. from Peru, P. steyermarkii and P. umbellifera, both from northern Brazil and Venezuela. New observations concerning floral biology and ecology, fruits and epigeous germination are presented: The petals are found to remain tightly and permanently connate, forming a cap, which protects the poricidal anthers from moisture and is shed as a whole in the course of buzz pollination. Full descriptions, including illustrations of species, a key for identification, a distribution map and a list of exsiccatae are provided. A new key for distinguishing between Perissocarpa and Elvasia is also presented. Chapters on wood anatomy and pollen morphology are contributed by B. Kartusch and H. Halbritter, respectively. Key words: Ochnaceae, Perissocarpa, Elvasia, floral biology and ecology, buzz pollination, South America, Brazil, Peru, Venezuela, wood anatomy, pollen morphology, growth form. Zusammenfassung Die Gattung Perissocarpa (Ochnaceae) wird einer Revision unterzogen und umfaßt nunmehr 3 Arten (P. ondox sp.n. aus Peru, P. steyermarkii und P. umbellifera, beide aus Nord-Brasilien und Venezuela). Neue Beobachtungen zur Biologie und Ökologie der Blüten, den Früchten und zur epigäischen Keimung werden vorgestellt: Beispielsweise bleiben die Kronblätter andauernd eng verbunden und bilden eine kappen-ähnliche Struktur, die die poriziden Antheren vor Nässe schützt und im Verlaufe der "buzz pollination" als Ganzes abgeworfen wird. -

Drupe. Fruit with a Hard Endocarp (Figs. 67 and 71-73); E.G., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres Guazumaefolia, Sterculia)

Fig. 71. Fig. 72. Fig. 73. Drupe. Fruit with a hard endocarp (figs. 67 and 71-73); e.g., and Sterculiaceae (Helicteres guazumaefolia, Sterculia). Anacardiaceae (Spondias purpurea, S. mombin, Mangifera indi- Desmopsis bibracteata (Annonaceae) has aggregate follicles ca, Tapirira), Caryocaraceae (Caryocar costaricense), Chrysobal- with constrictions between successive seeds, similar to those anaceae (Licania), Euphorbiaceae (Hyeronima), Malpighiaceae found in loments. (Byrsonima crispa), Olacaceae (Minquartia guianensis), Sapin- daceae (Meliccocus bijugatus), and Verbenaceae (Vitex cooperi). Samaracetum. Aggregate of samaras (fig. 74); e.g., Aceraceae (Acer pseudoplatanus), Magnoliaceae (Liriodendron tulipifera Hesperidium. Septicidal berry with a thick pericarp (fig. 67). L.), Sapindaceae (Thouinidium dodecandrum), and Tiliaceae Most of the fruit is derived from glandular trichomes. It is (Goethalsia meiantha). typical of the Rutaceae (Citrus). Multiple Fruits Aggregate Fruits Multiple fruits are found along a single axis and are usually coalescent. The most common types follow: Several types of aggregate fruits exist (fig. 74): Bibacca. Double fused berry; e.g., Lonicera. Achenacetum. Cluster of achenia; e.g., the strawberry (Fra- garia vesca). Sorosis. Fruits usually coalescent on a central axis; they derive from the ovaries of several flowers; e.g., Moraceae (Artocarpus Baccacetum or etaerio. Aggregate of berries; e.g., Annonaceae altilis). (Asimina triloba, Cananga odorata, Uvaria). The berries can be aggregate and syncarpic as in Annona reticulata, A. muricata, Syconium. Syncarp with many achenia in the inner wall of a A. pittieri and other species. hollow receptacle (fig. 74); e.g., Ficus. Drupacetum. Aggregate of druplets; e.g., Bursera simaruba THE GYMNOSPERM FRUIT (Burseraceae). Fertilization stimulates the growth of young gynostrobiles Folliacetum. Aggregate of follicles; e.g., Annonaceae which in species such as Pinus are more than 1 year old. -

Native Trees of Georgia.Pdf

NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION J. Frederick Allen Director Tenth Printing - 2000 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Guidance Document for Tree Conservation, Landscape, and Buffer Requirements Article III Section 3.2

Guidance Document For Tree Conservation, Landscape, and Buffer Requirements Article III Section 3.2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Revision History ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Technical Standards ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Tree Measurements .......................................................................................................................... 2 2. Specimen Trees ................................................................................................................................. 4 3. Boundary Tree ................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Tree Density Calculation ................................................................................................................... 5 Tree Removal Requirements ...................................................................................................................... 11 Tree Care ..................................................................................................................................................... 12 1. Planting ........................................................................................................................................... 12 2. Mulching ........................................................................................................................................ -

Peach Fruit Fly, Bactrocera Zonata, Host List the Berries, Fruit, Nuts and Vegetables of the Listed Plant Species Are Now Considered Host Articles for B

June 2017 Peach fruit fly, Bactrocera zonata, Host List The berries, fruit, nuts and vegetables of the listed plant species are now considered host articles for B. zonata. Unless proven otherwise, all cultivars, varieties, and hybrids of the plant species listed herein are considered suitable hosts of B. zonata. Scientific Name Common Name Aegle marmelos (L.) Correa Baeltree Afzelia xylocarpa (Kurz) Craib Doussie Annona reticulata L. Custard apple Annona squamosa L. Sugar apple Careya arborea Roxb. Patana oak Carica papaya L. Papaya Casimiroa edulis La Llave & Lex. White sapote Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.) Matsum. & Nakai Watermelon Citrus aurantium L. Sour orange Citrus limon (L.) Burm. f. Lemon Citrus nobilis x Citrus deliciosa Ten. Kinnow Citrus paradisi Macfad. Grapefruit Citrus reticulata Blanco Mandarin orange Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck Orange Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt Ivy gourd Cucumis sativus L. Cucumber Cydonia oblonga Mill. Quince Elaeocarpus hygrophilus Kurz Ma-kok-nam Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl. Loquat Ficus carica L. Fig Grewia asiatica L. Phalsa Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. Bottle gourd Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. Angled loofah Luffa spp. Tori Malpighia emarginata DC. Barbados cherry Malus pumila Mill. Apple Malus sylvestris (L.) Mill. Crab apple Mangifera indica L. Mango Manilkara zapota (L.) P. Royen Sapodilla Mimusops elengi L. Spanish cherry Momordica charantia L. Bitter melon Olea europaea L. Olive Persea americana Mill. Avocado Phoenix dactylifera L. Date palm Prunus armeniaca L. Apricot Prunus avium (L.) L. Sweet cherry Prunus domestica L. Plum Prunus persica (L.) Batsch Peach Prunus sp. N/A Psidium cattleyanum Sabine Strawberry guava Psidium guajava L. Guava Punica granatum L. Pomegranate Putranjiva roxburghii Wall. -

TYPES of FRUITS Botanically, a Fruit Develops from a Ripe Ovary Or Any Floral Parts on the Basis of Floral Parts They Develop, Fruits May Be True Or False

TYPES OF FRUITS Botanically, a fruit develops from a ripe ovary or any floral parts on the basis of floral parts they develop, fruits may be true or false. True Fruits: A true fruit or eucarp is a mature or ripened ovary, developed after fertilization, e.g., Mango, Maize, Grape etc. False Fruits: A false fruit or pseudo-carp is derived from the floral parts other than ovary, e.g., peduncle in cashew-nut, thalamus in apple, pear, gourd and cucumber; fused perianth in mulberry and calyx in Dillenia. Jack fruit and pine apple are also false fruits as they develop from the entire inflorescence. False fruits are also called spurious or accessory fruits. Parthenocarpic fruits: These are seedless fruits that are formed without fertilization, e.g., Banana. Now a day many seedless grapes, oranges and water melones are being developed by horticulturists. Pomology is a branch of horticulture that deals with Types of Fruits: A fruit consists of pericarp and seeds. Seeds are fertilized and ripened ovules. The pericarp develops from the ovary wall and may be dry or fleshy. When fleshy, pericarp is differentiated into outer epicarp, middle mesocarp and inner endocarp. On the basis of the above mentioned features, fruits are usually classified into three main groups: (1) Simple, (2) Aggregate and (3) Composite or Multiple fruits. 1. Simple Fruits: When a single fruit develops from a single ovary of a single flower, it is called a simple fruit. The ovary may belong to a monocarpellary simple gynoecium or to a polycarpellary syncarpous gynoecium. There are two categories of simple fruits—dry and fleshy. -

Chapter 6 ENUMERATION

Chapter 6 ENUMERATION . ENUMERATION The spermatophytic plants with their accepted names as per The Plant List [http://www.theplantlist.org/ ], through proper taxonomic treatments of recorded species and infra-specific taxa, collected from Gorumara National Park has been arranged in compliance with the presently accepted APG-III (Chase & Reveal, 2009) system of classification. Further, for better convenience the presentation of each species in the enumeration the genera and species under the families are arranged in alphabetical order. In case of Gymnosperms, four families with their genera and species also arranged in alphabetical order. The following sequence of enumeration is taken into consideration while enumerating each identified plants. (a) Accepted name, (b) Basionym if any, (c) Synonyms if any, (d) Homonym if any, (e) Vernacular name if any, (f) Description, (g) Flowering and fruiting periods, (h) Specimen cited, (i) Local distribution, and (j) General distribution. Each individual taxon is being treated here with the protologue at first along with the author citation and then referring the available important references for overall and/or adjacent floras and taxonomic treatments. Mentioned below is the list of important books, selected scientific journals, papers, newsletters and periodicals those have been referred during the citation of references. Chronicles of literature of reference: Names of the important books referred: Beng. Pl. : Bengal Plants En. Fl .Pl. Nepal : An Enumeration of the Flowering Plants of Nepal Fasc.Fl.India : Fascicles of Flora of India Fl.Brit.India : The Flora of British India Fl.Bhutan : Flora of Bhutan Fl.E.Him. : Flora of Eastern Himalaya Fl.India : Flora of India Fl Indi. -

Looking Under the Veneer (PDF, 1.75

Looking Under the Veneer IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL ON EU TIMBER TRADE CONTROL: * FOCUS ON CITES-LISTED TREES by Alexandre Affre, Wolfgang Kathe and Caroline Raymakers Document produced under a Service Contract with the European Commission Brussels, March 2004 Report to the European Commission in completion of Contract B4-3040/2002/340550/MAR/E3 March 2004 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit the European Commission as the copyright owner. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission or TRAFFIC Europe. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission, TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Suggested citation: Affre, A., Kathe, W. and Raymakers, C. (2004). Looking Under the Veneer. Implementation Manual on EU Timber Trade Control: Focus on CITES-Listed Trees. by TRAFFIC Europe. Report to the European Commission, Brussels. * Cover: CITES-listed trees - species included in the Appendices of CITES and in the Annexes of the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations (Council Regulation (EC) No. 338/97; Commission Regulations (EC) No. 1808/2001 and No. 1497/2003) Cover picture: Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata) – Belgium Customs, Antwerp (2003) The TRAFFIC symbol Copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. -

Lilium Polyphyllum D

Marsland Press Journal of American Science 2009;5(5):85-90 Anatomical features of Lilium polyphyllum D. Don ex Royle (Liliaceae) Anurag Dhyani1, Yateesh Mohan Bahuguna1, Dinesh Prasad Semwal2, Bhagwati Prasad Nautiyal3, Mohan Chandra Nautiyal1 1. High Altitude Plant Physiology Research Centre, Srinagar, Pin- 246174, Uttarakhand, INDIA 2. Department of Botany, Delhi University, Pin-110007, Delhi, INDIA 3. Department of Horticulture, Aromatic and Medicinal Plant, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Pin- 796001, Mizoram, INDIA [email protected] Abstract: Present paper reports anatomical investigation of Lilium polyphyllum, a critically endangered important medicinal herb. Plant samples were collected from Dhanolti, a temperate region in North-west Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India. Transverse sections of plant parts viz., stem, leaf, anther, stigma, ovary, seed, bulb scale, bulb peel and root were investigated. In leaves, stomata are hypostomatic and anomocytic type. Pollen shape was ellipsoid and its surface was reticulate, it also possesses oil drops. Ovary is superior and having axile placentation, ovules are anatropous. Sections of bulb scale show eccentric type starch grains and tracheids. Stem section show scattered vascular bundles. These anatomical features will help to provide information of taxonomic significance. [Journal of American Science 2009; 5(5): 85-90]. (ISSN: 1545-1003). Key Words: Anatomy; Oil drop; Pollen; Starch grains; Stomata; Tracheids 1. Introduction: The taxonomic classification divides the genus Lilium polyphyllum is a bulbous, perennial herb Lilium into seven sections (Comber, 1949; De Jong, (Figure 1, 2) and recently reported as critically 1974) with approximately 100 species distributed endangered (Ved et al., 2003). The species found in throughout the cold and temperate region of the North-west Himalaya in India to westward of northern hemisphere.