Thomas Reid on Signs and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning/Teaching Philosophy in Sign Language As a Cultural Issue

DOI: 10.15503/jecs20131-9-19 Journal of Education Culture and Society No. 1_2013 9 Learning/teaching philosophy in sign language as a cultural issue Maria de Fátima Sá Correia [email protected] Orquídea Coelho [email protected] António Magalhães [email protected] Andrea Benvenuto [email protected] Abstract This paper is about the process of learning/teaching philosophy in a class of deaf stu- dents. It starts with a presentation of Portuguese Sign Language that, as with other sign lan- guages, is recognized as a language on equal terms with vocal languages. However, in spite of the recognition of that identity, sign languages have specifi city related to the quadrimodal way of their production, and iconicity is an exclusive quality. Next, it will be argued that according to linguistic relativism - even in its weak version - language is a mould of thought. The idea of Philosophy is then discussed as an area of knowledge in which the author and the language of its production are always present. Finally, it is argued that learning/teaching Philosophy in Sign Language in a class of deaf students is linked to deaf culture and it is not merely a way of overcoming diffi culties with the spoken language. Key words: Bilingual education, Deaf culture, Learning-teaching Philosophy, Portuguese Sign Language. According to Portuguese law (Decreto-Lei 3/2008 de 7 de Janeiro de 2008 e Law 21 de 12 de Maio de 2008), in the “escolas de referência para a educação bilingue de alunos surdos” (EREBAS) (reference schools for bilingual education of deaf stu- dents) deaf students have to attend classes in Portuguese Sign Language. -

Vol. 62, No. 3; September 1984 PUTNAM's PARADOX David Lewis Introduction. Hilary Putnam Has Devised a Bomb That Threatens To

Australasian Journal of Philosophy Vol. 62, No. 3; September 1984 PUTNAM'S PARADOX David Lewis Introduction. Hilary Putnam has devised a bomb that threatens to devastate the realist philosophy we know and love. 1 He explains how he has learned to stop worrying and love the bomb. He welcomes the new order that it would bring. (RT&H, Preface) But we who still live in the target area do not agree. The bomb must be banned. Putnam's thesis (the bomb) is that, in virtue of considerations from the theory of reference, it makes no sense to suppose that an empirically ideal theory, as verified as can be, might nevertheless be false because the world is not the way the theory says it is. The reason given is, roughly, that there is no semantic glue to stick our words onto their referents, and so reference is very much up for grabs; but there is one force constraining reference, and that is our intention to refer in such a way that we come out right; and there is no countervailing force; and the world, no matter what it is like (almost), will afford some scheme of reference that makes us come out right; so how can we fail to come out right? 2 Putnam's thesis is incredible. We are in the presence of paradox, as surely as when we meet the man who offers us a proof that there are no people, and in particular that he himself does not exist. 3 It is out of the question to follow the argument where it leads. -

Aristotle's Doctrine of Signs and Semiotic Reading of His

167 ARISTOTLE’S DOCTRINE OF SIGNS AND SEMIOTIC READING OF HIS “PHYSICS” Anna MAKOLKIN1 АРИСТОТЕЛЕВСКОЕ УЧЕНИЕ О ЗНАКАХ И СЕМИОТИЧЕСКОЕ ЧТЕНИЕ ЕГО «ФИЗИКИ» Анна МАКОЛКИН Abstract. The purpose of this contribution is twofold– to introduce contemporary scholars to the forgotten Aristotle’s Doctrine of Signs and demonstrate how it can be constructively applied to the new analysis of his famed “Physics” and provide its re-interpretation. Subject to such semiotic analysis, Aristotle’s “Physics” reveals additional, previously undisclosed aspects of his teaching and novel unexpected features of this particular work, making it more meaningful for modern science at large. The strikingly new and unexpected characteristics of this treatise appear thanks to the creative application of the Nature/Culture paradigm, neglected by the modern scholars but encoded in Aristotle’s semiotic theories. The world is seen by Aristotle as an “Empire of Signs”, both natural and cultural, and man is presented as a sign-producing animal, seeking new knowledge. His overall philosophy is thus expanded in different ways thanks to the new semiotic method, offering more comprehensive analysis of Cosmos and more innovative analytical vision. Read semiotically, Aristotle’s “Physics” opens new previously undisclosed vistas of the world, as well as new aspects of human cognition. Aristotle’s challenges what future scholars would study in isolation, and solely as parts of philosophy, by proposing to treat Cosmos and man in it as an organic Whole. In contrast, Aristotle suggests to see Cosmos as an “abundance of signs” which signify phenomena, the relationship between them and their impact upon each other and human life. -

1 Hilary Putnam, Reason, Truth and History, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979). Henceforth 'RTH'. the Position Th

[The Journal of Philosophical Research XVII (1992): 313-345] Brains in a Vat, Subjectivity, and the Causal Theory of Reference Kirk Ludwig Department of Philosophy University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611-8545 1. Introduction In the first chapter of Reason, Truth and History,1 Putnam argued that it is not epistemically possible that we are brains in a vat (of a certain sort). If his argument is correct, and can be extended in certain ways, then it seems that we can lay to rest the traditional skeptical worry that most or all of our beliefs about the external world are false. Putnam’s argument has two parts. The first is an argument for a theory of reference2 according to which we cannot refer to an object or a type of object unless we have had a certain sort of causal interaction with it. The second part argues from this theory to the conclusion that we can know that we are not brains in a vat. In this paper I will argue that Putnam’s argument to show that we cannot be brains in a vat is unsuccessful. However, the flaw is not in the argument from the theory of reference to the conclusion 1 Hilary Putnam, Reason, Truth and History, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979). Henceforth ‘RTH’. The position that Putnam advances in this first chapter is one that in later chapters of RTH he abandons in favor of the position that he calls ‘internal realism’. He represents the arguments he gives in chapter 1 as a problem posed for the ‘external realist’, who assumes the possibility of a God’s eye point of view. -

![Bertrand Russell's Work for Peace [To 1960]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3746/bertrand-russells-work-for-peace-to-1960-913746.webp)

Bertrand Russell's Work for Peace [To 1960]

�rticles BERTRAND RUSSELL’S WORK FOR PEACE [TO 1960] Bertrand Russell and Edith Russell Bertrand Russell may not have been aware of it, but he wrote part of the dossier that was submitted on his behalf for the Nobel Peace Prize. Before he had turned from the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament to the Committee of 100 and subsequent campaigns of the 1960s, his wife, Edith, was asked by his publisher, Sir Stanley Unwin, for an account of his work for peace. Unwin’s purpose is not known, but it is not incompatible with the next use of the document. Lady Russell responded: You have set me a task which I am especially glad to do, and I enclose a screed made up of remarks which I have extracted (the word is deliberate!) from my husband since the arrival of your letter. If there is any more information about any part of his work for peacez—zwhich has been and is, much more intensive and absorbing than this enclosure sounds as if it werez—z I should be glad to provide it if I can and if you will let me know. (7 Aug. 1960) The dictation, and her subsequent completion of the narrative (at RA1 220.024190), have not previously been published, though the “screed” was used several times. She had taken the dictation on 6 August 1960 and by next day had completed the account. Russell corrected her typescript by hand. Next we learn that Joseph Rotblat, Secretary-General of Pugwash, enclosed for her, on 2 March 1961, a copy of the “ex tracts” that were “sent to Norway” (RA1 625). -

A New Philosophy: Henri Bergson

A New Philosophy: Henri Bergson Edouard le Roy A New Philosophy: Henri Bergson Table of Contents A New Philosophy: Henri Bergson..........................................................................................................................1 Edouard le Roy...............................................................................................................................................1 Preface............................................................................................................................................................1 I. Method........................................................................................................................................................2 I......................................................................................................................................................................3 II.....................................................................................................................................................................5 III....................................................................................................................................................................9 IV.................................................................................................................................................................13 II. Teaching..................................................................................................................................................20 -

An Investigation Into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës

Journal of Feminist Scholarship Volume 10 Issue 10 Spring 2016 Article 5 Spring 2016 Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor University of Arkansas at Little Rock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Women's History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Taylor, Reed. 2018. "Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës." Journal of Feminist Scholarship 10 (Spring): 48-60. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jfs/vol10/ iss10/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Feminist Scholarship by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Taylor: Bodies and Contexts Bodies and Contexts: An Investigation into a Postmodern Feminist Reading of Averroës Reed Taylor, University of Arkansas at Little Rock Abstract: In this article, I contribute to the wider discourse of theorizing feminism in predominantly Muslim societies by analyzing the role of women’s political agency within the writings of the twelfth-century Islamic philosopher Averroës (Ibn Rushd, 1126–1198). I critically analyze Catarina Belo’s (2009) liberal feminist approach to political agency in Averroës by adopting a postmodern reading of Averroës’s commentary on Plato’s Republic. A postmodern feminist reading of Averroes’s political thought emphasizes contingencies and contextualization rather than employing a literal reading of the historical works. -

Aristotle on Sign-Inference and Related Forms Ofargument

12 Introduction degree oflogical sophistication about what is required for one thing to follow from another had been achieved. The authorities whose views are reported by Philodemus wrote to answer the charges of certain unnamed opponents, usually and probably rightly supposed to be Stoics. These opponents draw· on the resources of a logical STUDY I theory, as we can see from the prominent part that is played in their arguments by an appeal to the conditional (auvTJp.p.EvOV). Similarity cannot, they maintain, supply the basis of true conditionals of the Aristotle on Sign-inference and kind required for the Epicureans' inferences to the rion-evident. But instead of dismissing this challenge, as Epicurus' notoriously Related Forms ofArgument contemptuous attitude towards logic might have led us to expect, the Epicureans accept it and attempt· to show that similarity can THOUGH Aristotle was the first to make sign-inference the object give rise to true conditionals of the required strictness. What is oftheoretical reflection, what he left us is less a theory proper than a more, they treat inference by analogy as one of two species of argu sketch of one. Its fullest statement is found in Prior Analytics 2. 27, ment embraced by the method ofsimilarity they defend. The other the last in a sequence offive chapters whose aim is to establish that: is made up of what we should call inductive arguments or, if we .' not only are dialectical and demonstrative syllogisms [auAAoyw,uol] effected construe induction more broadly, an especially prominent special by means of the figures [of the categorical syllogism] but also rhetorical case of inductive argument, viz. -

Aristotle-Rhetoric.Pdf

Rhetoric Aristotle (Translated by W. Rhys Roberts) Book I 1 Rhetoric is the counterpart of Dialectic. Both alike are con- cerned with such things as come, more or less, within the general ken of all men and belong to no definite science. Accordingly all men make use, more or less, of both; for to a certain extent all men attempt to discuss statements and to maintain them, to defend themselves and to attack others. Ordinary people do this either at random or through practice and from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, the subject can plainly be handled systematically, for it is possible to inquire the reason why some speakers succeed through practice and others spontaneously; and every one will at once agree that such an inquiry is the function of an art. Now, the framers of the current treatises on rhetoric have cons- tructed but a small portion of that art. The modes of persuasion are the only true constituents of the art: everything else is me- rely accessory. These writers, however, say nothing about en- thymemes, which are the substance of rhetorical persuasion, but deal mainly with non-essentials. The arousing of prejudice, pity, anger, and similar emotions has nothing to do with the essential facts, but is merely a personal appeal to the man who is judging the case. Consequently if the rules for trials which are now laid down some states-especially in well-governed states-were applied everywhere, such people would have nothing to say. All men, no doubt, think that the laws should prescribe such rules, but some, as in the court of Areopagus, give practical effect to their thoughts 4 Aristotle and forbid talk about non-essentials. -

Sign Ordinance

SIGN ORDINANCE Adopted by Ord. No. 18-49 June 26, 2018 Table of Contents Section Subsection Heading Page 1.01 Purpose 4 1.02 Authority and Jurisdiction 4 1.03 Definitions 5 1.04 Permit Requirements 11 A Permit Required 11 B Application 11 C Fees 11 D Work without a Permit 11 E Permit Expiration 11 1.05 Sign Contractor Registration 12 A Requirement 12 B Timeframe 12 C Fees 12 D Violations 12 1.06 Sign Contractor Certificate of Insurance/Bond 12 A Requirement 12 B Cancellation 13 1.07 Inspections 13 A Compliance Inspections 13 B Periodic Inspections 13 C Notice of non-compliance 13 D Order of Removal 13 1.08 Sign Specifications and Design 14 A Compliance 14 B Visibility 14 C Restrictions 14 D Multiple Signs on a Property or Building 14 1.09 Sign Measurement 15 A Area 15 B Multiple Elements 16 C Height 17 D Supports 17 1.10 Prohibited Signs 18 1.11 Removal/Impoundment of Non-Compliant Signs 19 A Notification 19 B Expired Signs 19 C Failure to Comply 19 D Town-owned Property 19 1 1.12 Criteria for Permissible Signs 19 A Attached Signage 20 (1) Awning Sign 20 (2) Banner Sign 20 (3) Blade Sign 21 (4) Canopy Sign 22 (5) Construction Fence Sign 23 (6) Outdoor Machine Sign 24 (7) Projecting Sign 24 (8) Vehicular Sign 25 (9) Wall Sign 25 (10) Window Sign 27 B Freestanding Signage 27 (1) Development Sign 27 (2) Downtown Sign 28 (3) Flags 29 (4) Human Sign 30 (5) Incidental Sign 30 (6) Inflatable Sign 31 (7) Monument Sign 32 (8) Political Sign 34 (9) Residential Sign 36 (10) Restaurant Use Drive-through Sign 36 (11) Sandwich Board (A-frame) Sign -

The Bergsonian Moment: Science and Spirit in France, 1874-1907

THE BERGSONIAN MOMENT: SCIENCE AND SPIRIT IN FRANCE, 1874-1907 by Larry Sommer McGrath A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Larry Sommer McGrath All Rights Reserved Intended to be blank ii Abstract My dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of a distinct movement in modern Europe that I call “scientific spiritualism.” I argue that the philosopher Henri Bergson emerged from this movement as its most celebrated spokesman. From the 1874 publication of Émile Boutroux’s The Contingency of the Laws of Nature to Bergson’s 1907 Creative Evolution, a wave of heterodox thinkers, including Maurice Blondel, Alfred Fouillée, Jean-Marie Guyau, Pierre Janet, and Édouard Le Roy, gave shape to scientific spiritualism. These thinkers staged a rapprochement between two disparate formations: on the one hand, the rich heritage of French spiritualism, extending from the sixteenth- and seventeeth-century polymaths Michel de Montaigne and René Descartes to the nineteenth-century philosophes Maine de Biran and Victor Cousin; and on the other hand, transnational developments in the emergent natural and human sciences, especially in the nascent experimental psychology and evolutionary biology. I trace the influx of these developments into Paris, where scientific spiritualists collaboratively rejuvenated the philosophical and religious study of consciousness on the basis of the very sciences that threatened the authority of philosophy and religion. Using original materials gathered in French and Belgian archives, I argue that new reading communities formed around scientific journals, the explosion of research institutes, and the secularization of the French education system, brought about this significant, though heretofore neglected wave of thought. -

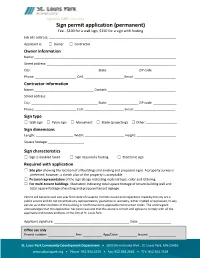

Sign Permit Application

Sign permit application (permanent) Fee - $100 for a wall sign, $150 for a sign with footing Job site address: _______________________________________________________________________ Applicant is: ☐ Owner ☐ Contractor Owner information Name: _______________________________________________________________________________ Street address: ________________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________________________ State: _________________ ZIP code: _____________ Phone: _______________________ Cell: ______________________ Email: _______________________ Contractor information Name: _________________________________ Contact: ______________________________________ Street address: ________________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________________________ State: _________________ ZIP code: _____________ Phone: _______________________ Cell: ______________________ Email: _______________________ Sign type ☐ Wall sign ☐ Pylon sign ☐ Monument ☐ Blade (projecting) ☐ Other: _________________ Sign dimensions Length: _____________________ Width: ______________________ Height: ______________________ Square footage: ____________________ Sign characteristics ☐ Sign is doubled faced ☐ Sign required a footing ☐ Electronic sign Required with application ☐ Site plan showing the location of all buildings and existing and proposed signs. A property survey is preferred; however, a sketch plan of the property is acceptable. ☐ Pictorial representation of the sign design indicating material