Abstracts EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptionsjournal of International Affairs

PERCEPTIONSJOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS PERCEPTIONS Summer-Autumn 2015 Volume XX Number 2-3 XX Number 2015 Volume Summer-Autumn PERCEPTIONS The Great War and the Ottoman Empire: Origins Ayşegül SEVER and Nuray BOZBORA Redefining the First World War within the Context of Clausewitz’s “Absolute War” Dystopia Burak GÜLBOY Unionist Failure to Stay out of the War in October-November 1914 Feroz AHMAD Austro-Ottoman Relations and the Origins of World War One, 1912-14: A Reinterpretation Gül TOKAY Ottoman Military Reforms on the eve of World War I Odile MOREAU The First World War in Contemporary Russian Histography - New Areas of Research Iskander GILYAZOV Summer-Autumn 2015 Volume XX - Number 2-3 ISSN 1300-8641 PERCEPTIONS Editor in Chief Ali Resul Usul Deputy Editor Birgül Demirtaş Managing Editor Engin Karaca Book Review Editor İbrahim Kaya English Language and Copy Editor Julie Ann Matthews Aydınlı International Advisory Board Bülent Aras Mustafa Kibaroğlu Gülnur Aybet Talha Köse Ersel Aydınlı Mesut Özcan Florian Bieber Thomas Risse Pınar Bilgin Lee Hee Soo David Chandler Oktay Tanrısever Burhanettin Duran Jang Ji Hyang Maria Todorova Ahmet İçduygu Ole Wæver Ekrem Karakoç Jaap de Wilde Şaban Kardaş Richard Whitman Fuat Keyman Nuri Yurdusev Homepage: http://www.sam.gov.tr The Center for Strategic Research (Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi- SAM) conducts research on Turkish foreign policy, regional studies and international relations, and makes scholarly and scientific assessments of relevant issues. It is a consultative body of the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs providing strategic insights, independent data and analysis to decision makers in government. As a nonprofit organization, SAM is chartered by law and has been active since May 1995. -

Settler Soldiers, Colonial Categories and the Centenary of the First World War

This is a repository copy of “The Forgotten of This Tribute”: Settler Soldiers, Colonial Categories and the Centenary of the First World War. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/142187/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Eldridge, C orcid.org/0000-0002-9159-3547 (2019) “The Forgotten of This Tribute”: Settler Soldiers, Colonial Categories and the Centenary of the First World War. History and Memory, 31 (2). pp. 3-44. ISSN 0935-560X https://doi.org/10.2979/histmemo.31.2.0003 © 2019, Indiana University Press. This is an author produced version of an article published in History and Memory. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self- archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ “The forgotten of this tribute”: Settler Soldiers, Colonial Categories, and the Centenary of the First World War 1 Abstract: This article uses the Centenary of the First World War to explore how colonial Frenchcategories Algeria, have beenit argues mobilized that inthe memory Centenary projects. -

Race and WWI

Introductions, headnotes, and back matter copyright © 2016 by Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y. Cover photograph: American soldiers in France, 1918. Courtesy of the National Archives. Woodrow Wilson: Copyright © 1983, 1989 by Princeton University Press. Vernon E. Kniptash: Copyright © 2009 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Mary Borden: Copyright © Patrick Aylmer 1929, 2008. Shirley Millard: Copyright © 1936 by Shirley Millard. Ernest Hemingway: Copyright © 1925, 1930 by Charles Scribner’s Sons, renewed 1953, 1958 by Ernest Hemingway. * * * The readings presented here are drawn from World War I and America: Told by the Americans Who Lived It. Published to mark the centenary of the Amer- ican entry into the conflict, World War I and America brings together 128 diverse texts—speeches, messages, letters, diaries, poems, songs, newspaper and magazine articles, excerpts from memoirs and journalistic narratives— written by scores of American participants and observers that illuminate and vivify events from the outbreak of war in 1914 through the Armistice, the Paris Peace Conference, and the League of Nations debate. The writers col- lected in the volume—soldiers, airmen, nurses, diplomats, statesmen, political activists, journalists—provide unique insight into how Americans perceived the war and how the conflict transformed American life. It is being published by The Library of America, a nonprofit institution dedicated to preserving America’s best and most significant writing in handsome, enduring volumes, featuring authoritative texts. You can learn more about World War I and America, and about The Library of America, at www.loa.org. For materials to support your use of this reader, and for multimedia content related to World War I, visit: www.WWIAmerica.org World War I and America is made possible by the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities. -

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920

Trianon 1920–2020 Some Aspects of the Hungarian Peace Treaty of 1920 TRIANON 1920–2020 SOME ASPECTS OF THE HUNGARIAN PEACE TREATY OF 1920 Edited by Róbert Barta – Róbert Kerepeszki – Krzysztof Kania in co-operation with Ádám Novák Debrecen, 2021 Published by The Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft. and the University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History Refereed by Levente Püski Proofs read by Máté Barta Desktop editing, layout and cover design by Zoltán Véber Járom Kulturális Egyesület A könyv megjelenését a Nemzeti Kulturális Alap támomgatta. The publish of the book is supported by The National Cultural Fund of Hungary ISBN 978-963-490-129-9 © University of Debrecen, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of History, 2021 © Debreceni Universitas Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft., 2021 © The Authors, 2021 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy- ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Printed by Printart-Press Kft., Debrecen Managing Director: Balázs Szabó Cover design: A contemporary map of Europe after the Great War CONTENTS Foreword and Acknowledgements (RÓBERT BARTA) ..................................7 TRIANON AND THE POST WWI INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS MANFRED JATZLAUK, Deutschland und der Versailler Friedensvertrag von 1919 .......................................................................................................13 -

Amir in Paris to Attend Global Peace Forum

BUSINESS | 14 SPORT | 19 Italy stands by main Australia end pillars of budget as EU losing streak to keep deadline nears series alive Saturday 10 November 2018 | 2 Rabia I 1440 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 23 | Number 7706 | 2 Riyals Amir in Paris to attend global peace forum Qatar's grant THE PENINSULA to Gaza civil Conceived as an annual challenges and ensuring durable gathering of all actors of peace. To support collective action, servants DOHA: Amir H H Sheikh Tamim bin global governance, from it gathers all actors of global gov- Hamad Al Thani arrived in the ernance under one roof for three French capital, Paris, yesterday states and international days – states, international organi- disbursed evening to participate in Paris Peace organisations to civil sations, local governments, NGOs THE PENINSULA Forum, which will be held society, the Peace and foundations, companies, tomorrow, at the invitation of the Forum features projects experts, journalists, trade unions, President of the French Republic, religious groups and citizens. DOHA: The Finance Ministry Emmanuel Macron. and initiatives meant The Forum is centered on those in Gaza Strip has started HH the Amir is accompanied by at improving global who seek to develop solutions for disbursement of the Qatari an official delegation, QNA reported. governance in five key today’s trans-border challenges. It financial grant to 27,000 civil The Paris Peace Forum was ini- domains. is focused on their 120 governance servants, while the salaries of tiated by the French President to projects and initiatives from around the rest will be paid from the revive collective governance, inter- the world, selected from 850 appli- local revenues. -

Whanganui Woman for Armistice Day’ Poem

Vol. 34, No. 43, November 8, 2018 52 Ingestre Street, Wanganui. Phone 345 3666 or 345 3655, fax 345 2644, email [email protected] Worldwide project features ‘Whanganui Woman for Armistice Day’ poem ‘I suppose you are still Scotland, farming in Margaret, and Margaret BY DOUG DAVIDSON the Whanganui district !' Jayne Workman is one of only three New Zea- before building a house to their husbands in landers invited to write a 100 words on some- would be no more men in Brassey Road. It was # one alive during WW1 as part of a world-wide left to wear them’.” Only to this address ‘Miss The project was initiat- project involving 100 writers. !" M Wilson, Alton Villa, ed by ‘26’ – which Jayne Their ‘centenas’ are As part of her research, " St John’s Hill’ that the describes as “a not-for- being progressively she approached the ## wartime letters were (( released each day with Whanganui Regional after returning in 1920, addressed. Jayne is still to inspire a greater love [ Museum archives and they were married. “Sad- trying to ascertain its of words, in business and before Armistice Day was shown an envelope P%O '/ in life” - in partnership Centenary on November of letters sent to Marga- a marine engineer, was were pictures of a young with the Imperial War 11. They can be read at ret ‘Mag’ Wilson from '( Margaret in the envelope Museum. 26 has led a www.1914.org. her brother, Arthur and Whanganui Port just nine of letters. number of other creative She wanted to write [ QR years later.” She found out that writing briefs in the last about someone from McKinnon, from Tren- Margaret did remarry another brother, Jim, 15 years, including one Whanganui - a woman tham Camp in the Hutt but did not have chil- also enlisted and served with the Victoria and Al- - to recognise not only Valley to the trenches on dren. -

Readings: Isaiah 2:1-4; Psalm 29; Romans 12:9-21; John 14:25-28, 16:32-33

Preached at St. David's 11/11/2018 Armistice Day / 1 Armistice Day Readings: Isaiah 2:1-4; Psalm 29; Romans 12:9-21; John 14:25-28, 16:32-33 At 11am on 11th November 1918 the guns of the Western Front fell silent after more than four years continuous warfare. It is not surprising that we remember that moment with silence. After the continual noise of bloodshed and devastation, agony and violence, there was now silence. And in the silence, we now remember. But after the silence there was celebration, that peace had finally come. Those who knew the cost of war could truly celebrate peace. Today we need to remember and celebrate. REMEMBERING The Cathedral As we gather in this place we should remember. Not only do we have the photographic display of Tasmanians involved in WW1. We have so many memorials. As you enter the building there is the honour board of those from this Cathedral who served in the so called Great War. We have windows given in memory of those who died in France. Our lectern and brass sanctuary rails are giving in memory of the fallen. We have the memorial to Eric Campbell, the last Anzac. We have this flag carried by Mrs Roberts before every troop movement to and from Angelsea barracks. So many went, far fewer came back, and many of those who did were ruined shells of men. My Family Their service and sacrifice should not be forgotten. All this was brought home to me when sorting through some of my parents’ items when this box was found. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 793 Monday No. 202 5 November 2018 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Deaths of Members..........................................................................................................1527 Questions Devolution: Sheffield City Region................................................................................1527 Ex-Offenders: Training and Employment.....................................................................1530 Pornographic Websites: Age Verification......................................................................1532 Design Engineer Construct Programme .......................................................................1534 Knife Crime Private Notice Question ................................................................................................1537 Further Education Bodies (Insolvency) Regulations 2018 Motion to Approve ........................................................................................................1540 Armistice Day: Centenary Motion to Take Note.....................................................................................................1540 Brexit: Arrangements for EU Citizens Statement......................................................................................................................1568 Universal Credit Statement......................................................................................................................1571 Armistice Day: Centenary Motion to Take Note (Continued) ................................................................................1583 -

PDF (All Devices)

Published by: The Irish Times Limited (Irish Times Books) © The Irish Times 2016. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of The Irish Times Limited, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographic rights organisation or as expressly permitted by law. Contents To my daughter Betty, the gift of God ........................................................................... 1 The heroic dead of Ireland – Marshal Foch’s tribute .................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 Casualties in Irish regiments on the first day of the Battle of the Somme .................. 10 How The Irish Times reported the Somme .................................................................. 13 An Irishman’s Diary ...................................................................................................... 17 The Irish Times editorial ............................................................................................... 20 Death of daughter of poet Thomas Kettle ................................................................... 22 How the First World War began .................................................................................. 24 Preparing for the ‘Big Push’ ........................................................................................ -

ARDS and NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 24 January

ARDS AND NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 24 January 2019 Dear Sir/Madam You are hereby invited to attend a meeting of the Ards and North Down Borough Council which will be held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, The Castle, Bangor on Wednesday, 30 January 2019 commencing at 7.00pm. Yours faithfully Stephen Reid Chief Executive Ards and North Down Borough Council A G E N D A 1. Prayer 2. Apologies 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayor’s Business 5. Mayor and Deputy Mayor Engagements for the Month (To be tabled) 6. Minutes of Meeting of Council dated 19 December 2018 (Copy attached) 7. Minutes of Committees (Copies attached) 7.1. Audit Committee dated 17 December 2018 7.2. Special Planning Committee dated 18 December 2018 7.3. Special Corporate Services Committee dated 7 January 2019 7.4. Environment Committee dated 9 January 2019 7.5. Regeneration and Development Committee dated 10 January 2019 7.6. Corporate Services Committee dated 15 January 2019 7.7. Community and Wellbeing Committee dated 16 January 2019 7.8. Special Planning Committee dated 17 January 2019 8. Requests for Deputations 8.1 Retail NI, Hospitality Ulster and Manufacturing NI – District rate on non- domestic properties (Copy correspondence attached) 8.2 Northern Ireland Housing Executive – Housing Investment Plan for the Ards and North Down Borough (Copy correspondence attached) 8.3 Kilcooley Community Forum Ltd – Kilcooley 3G Pitch (Copy email attached) 9. Resolutions 9.1 Support for the Irish Language Act in Northern Ireland (Copy correspondence from the Donegal County Council attached) 10. Courses/Invitations etc 10.1 Northern Ireland Agribusiness Conference 2019 – Friday 8th March, Craigavon Civic Centre (Copy correspondence attached) 11. -

Report of Centenary End of Great War Working Group Meeting No 4 Tuesday 1St May 2018 at 6.15 PM the Stables Meeting Room at Aghadowey Parish Church

Report of Centenary End of Great War Working Group Meeting No 4 Tuesday 1st May 2018 at 6.15 PM The Stables meeting room at Aghadowey Parish Church Present Members: Councillors Clarke (Chair), Knight-McQuillan and Quigley RBL Reps: B Mills, J McCurdy, M McLaughlin, J Tait, R Galbraith Officers: P Donaghy, Democratic & Central Services Manager NO. ACTIONS 1. APOLOGIES K McMichael, S McClements, G Kane DSM 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Nil. 3. NOTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING HELD 11th April 2018 The DSM advised that the minutes had been presented to Council and actions progressed. 4. PUBLICITY Programme Details Launch photograph taken prior to meeting at Aghadowey War Memorial. The DSM circulated a draft of the artwork for the events programme (previously agreed by Council) and attached which would be published on Council’s website and other social media. Members of the Working Group offered comments and NO. ACTIONS suggested amendments. The DSM advised that the programme would be updated regularly. RBL concert Ballymoney – date still to be confirmed 13th and 20th October provisionally held. Remembrance Sunday Ballymoney – possibility of including erection of memorial DSM to Colonel Knox as part of the Remembrance Service. Add details of Armed Forces Day and Airwaves to programme. Press release A draft of a press release (attached) to accompany the launch photographs and programme of events and previously agreed by the Chair and the Mayor was circulated. Comments were offered. 5. BEACON LIGHTING CEREMONIES The Lord Lieutenant/ Deputies confirmed for ceremonies by RBLs. RBL reps Suggested that a report be taken to Council at same time as report requesting DSM Elected Member representation at Annual Remembrance Sunday Parades for Elected Member representation at Beacon Lighting Ceremonies. -

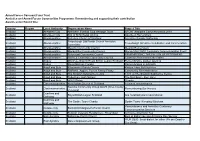

Remembering and Supporting Their Contribution Awards Under Round One

Armed Forces Covenant Fund Trust Armistice and Armed Forces Communities Programme: Remembering and supporting their contribution Awards under Round One Country Region Local Authority Organisation Name Project Title Scotland Aberdeen City Aberdeen Football Club Heritage Trust AFCHT Armistice Commemoration 2018 Scotland Aberdeen City Kirk of St Nicholas Uniting Aberdeen Remembers Scotland Aberdeenshire Belhelvie Church of Scotland Armistice Sunday Gathering Fraserburgh Old Parish Church Armistice Scotland Aberdeenshire Fraserburgh Armistice Celebration and Commeration Committee Scotland Aberdeenshire Mearns Community Council Mearns Remembers Scotland Aberdeenshire Monquhitter Community Council Monquhitter WW1 Centenary Commemoration Event Scotland Aberdeenshire Peterhead Community Council REMEMBERING THE FALLEN OF PETERHEAD Scotland Aberdeenshire Slains & Collieston Community Council Collieston Remembers the Fallen Scotland Angus Montrose Branch Royal British Legion Scotland Remembrance garden opening Scotland Angus Royal Marines Condor Remembrance in Arbroath Scotland Argyll and Bute Kilcalmonell Parish Church Kintyre: Here But Not Here Scotland Argyll and Bute RNRMW, Aggies, Forces Family Friday Community Rememberance Scotland Argyll and Bute The Scottish Submarine Centre 11/11 at The Scottish Submarine Centre Scotland Argyll and Bute Tobermory High School The Mull Boys - their story. Scotland Argyll and Bute WW100Islay Otranto Scotland Clackmannanshire Alva Parish Church of Scotland A time of remembrance Sauchie Community Group QAVS (Wee