Supporting Kakuma's Refugee Traders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expanding Teacher Support Through Mobile Mentoring in Kakuma Refugee Camp: Benefits and Challenges

Current Issues in Comparative Education (CICE) Volume 20, Issue 2, Special Issue 2018 Expanding Teacher Support through Mobile Mentoring in Kakuma Refugee Camp: Benefits and Challenges Mary Mendenhall Teachers College, Columbia University Makala Skinner Teachers College, Columbia University Sophia Collas Teachers College, Columbia University Sarah French Teachers College, Columbia University Introduction Governmental and non-governmental institutions alike have rallied around technology as a potential solution for addressing the dearth of quality educational opportunities and adequately trained teachers in many regions around the world (Burns, 2011; Carlson, 2013; Dahya, 2016). This is no less true in humanitarian and refugee contexts where technology is being used in myriad ways to connect teachers and learners with educational content and resources. A recent landscape review (Dahya, 2016) about the use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in these contexts stated that technology has the potential to support education for marginalized populations in crisis contexts, and that teacher training and student learning are the primary areas of focus for utilizing technology for education. In many settings, technology is used for the provision of lesson plans and curricula to deliver subject knowledge directly to students, to train or certify teachers, and to connect individuals and build community (Dryden-Peterson, Dahya, and Douhaibi, 2017; Power, 2012; Winthrop and Smith, 2012). Modes of delivery include computers, laptops, tablets, portable media players, e-readers, personal digital assistants, and mobile phones (Burns, 2011; Carlson, 2013; Winthrop and Smith, 2012; Dahya, 2016). Mobile phones have been singled out as a particularly useful device for communication due to their ubiquity, with the number of people in Africa, for example, with access to mobile phones far outstripping those with access to computers (Burns, 2011; Carlson, 2013; Dryden-Peterson, Dahya, and Douhaibi, 2017; UNESCO, 2012). -

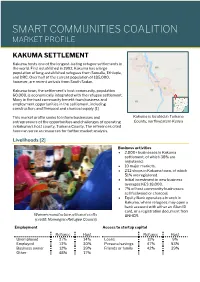

KAKUMA SETTLEMENT Kakuma Hosts One of the Longest-Lasting Refugee Settlements in the World

SMART COMMUNITIES COALITION MARKET PROFILE KAKUMA SETTLEMENT Kakuma hosts one of the longest-lasting refugee settlements in the world. First established in 1992, Kakuma has a large population of long-established refugees from Somalia, Ethiopia, and DRC. Over half of the current population of 185,000, however, are recent arrivals from South Sudan. Kakuma town, the settlement’s host community, population 60,000, is economically integrated with the refugee settlement. Many in the host community benefit from business and employment opportunities in the settlement, including construction, and firewood and charcoal supply. [1] This market profile seeks to inform businesses and Kakuma is located in Turkana entrepreneurs of the opportunities and challenges of operating County, northwestern Kenya in Kakuma’s host county, Turkana County. The references cited here can serve as resources for further market analysis. Livelihoods [2] Business activities • 2,000+ businesses in Kakuma settlement, of which 38% are registered. • 10 major markets. • 232 shops in Kakuma town, of which 51% are registered. • Initial investment in new business averages KES 18,000. • 7% of host community businesses sell fuelwood or charcoal. • Equity Bank operates a branch in Kakuma, where refugees may open a bank account with either an Alien ID card, or a registration document from Women manufacture artisanal crafts UNHCR. (credit: Norwegian Refugee Council) Employment Access to startup capital Refugee Host Refugee Host Unemployed 27% 14% Loans 11% 9% Employed 13% 30% Personal -

DGMQ's Africa Field Program in Kenya

DGMQ’s Africa Field Program in Kenya CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ), assisted by the Division of Global Health Protection, sponsors the Africa Field Program, administered from CDC’s Kenya office, which is dedicated to the improvement and promotion of health for refugees and immigrants. The DGMQ Africa Field Program’s major partners in this effort are the Kenya Medical Research Institute, International Organization for Migration, and UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugees in Africa y 2.7 million people with refugee or “refugee- like” status in Africa at the end of 2011 y 770,000 refugees in Kenya y 376,000 refugees in Ethiopia Core Activities y Coordinates activities to protect the health of refugees who resettle to the US y Conducts disease surveillance y Provides technical training and support y Builds capacity for healthcare partners y Strengthens international partnerships Women carrying water in Dadaab Refugee Camp. y Responds to outbreaks in Africa Dadaab and Kakuma Refugee Camps Role in Resettling African Refugees to Not far from the Somali border of Kenya lies the town the United States of Dadaab, home to over 450,000 refugees in what is Over the past 10 years, between 8,000 and 30,000 African the largest refugee camp in the world. The Kakuma refugees have resettled to the United States annually. To camp is closer to the border with Sudan, and has prevent infectious threats from entering the United States over 120,000 refugees. Refugees at both camps are and to promote refugee health, DGMQ faced with a host of medical problems which are compounded by the overcrowded conditions and y Develops guidelines to help physicians conduct medical limited access to care. -

Briefing-Kit May-2019-Approved.Pdf (Unhcr.Org)

KAKUMA CAMP AND KALOBEYEI SETTLEMENT BRIEFING KIT, MAY 2019 188,794 22 4,350 Refugees hosted at Kakuma camp Nationalities hosted in Individuals assisted to return and Kalobeyei settlement as of 12 Kakuma camp and Kalobeyei voluntarily through VolRep since May 2019 settlement February 2016 KEY FIGURES POPULATION FIGURES 42 ▪ OTHERS Partners including the ▪ ETH Kenyan Government Country of Origin ▪ COD South Sudan (108,888) SSD ▪ Somali (34,251) 5% ▪ SOM DR Congo (12,478) Ethiopia (10,440) Have of the population have Others (22,737) access to electricity 2,500 1,293 69% Approximate number of Permanent shelter units Of refugees access the businesses in Kakuma and constructed through CBI in Internet using Smart phones Kalobeyei Kalobeyei settlement since June 2018 Photo: An aerial image of the over 2,000 permanent shelter units constructed in Village One of Kalobeyei Integrated Settlement. UNHCR/Samuel Otieno Protection 5,794 13,127 99 Newly arrived asylum seekers Refugees logged in and used Individuals assisted to return registered since January 2019 KASI in 2019 through VolRep in 2019 1,684 Protection referrals made since in 2019 Refugees and host community take part in a basketball clinic dubbed ‘Kakuma Dreams Big’ organized by the Giants of Africa in Kakuma town. Key updates Leaders election in Kalobeyei: The Refugee Affairs by organizations working in Kakuma camp and Kalobeyei Secretariat (RAS), with the support of UNHCR and partners, settlement. As an innovative tool, KASI has promoted a more is planning to hold the first leaders election in the Kalobeyei efficient use of refugees existing data and ensures that their Settlement on 31st May 2019. -

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the Use of CERF Funds

Resident / Humanitarian Coordinator Report on the use of CERF funds RESIDENT / HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS KENYA UNDERFUNDED EMERGENCIES ROUND 1 2016 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR Siddharth Chatterjee REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. The After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted in May 2016 and involved the participation of all agencies (WFP, UNICEF, UNHCR, UNFPA, WHO) involved in the CERF response to refugees in Kakuma Camp. b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator (RC) Report was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team and by cluster/sector coordinators as outlined in the guidelines. YES NO The report was discussed in the Kenya Humanitarian Partners Team (KHPT) meeting in May 2017. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders as recommended in the guidelines (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant government counterparts)? YES NO A final approved version was shared for review after discussion in the KHPT in May 2017. 2 I. HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT TABLE 1: EMERGENCY ALLOCATION OVERVIEW (US$) Total amount required for the humanitarian response: USD 165,700,000 Source Amount CERF 3,998,746 Breakdown of total response COUNTRY-BASED POOL FUND (if applicable) funding received by source OTHER (bilateral/multilateral) 11,208,561 (UNHCR) TOTAL 15,207,307 TABLE 2: CERF EMERGENCY -

Iom Resettlement the Un Migration Agency Iomiom Resettlement Movements Resettlement and Movement Management Division

IOM RESETTLEMENT THE UN MIGRATION AGENCY IOMIOM RESETTLEMENT MOVEMENTS RESETTLEMENT AND MOVEMENT MANAGEMENT DIVISION IOM RESETTLEMENT Resettlement and Movement Management – RMM : [email protected] Migration Health Division – MHD : [email protected] Labour Mobility and Human Development – LHD : [email protected] INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 17 route des Morillons P.O. Box 17, 1211 Geneva 19 Switzerland T. +41 22 717 91 11 F. +41 22 798 61 50 [email protected], www.iom.int © 2019 International Organization for Migration (IOM) No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. PUB2019/050/R Cover: Members of Syrian family saying goodbye to their friends/countryman when leaving Kutina Reception center for asylum seekers towards their new permanent accommodation in Zagreb, supported by IOM through Croatia’s first resettlement programme. -

Rapid Assessment of Natural Resources Degradation in Areas Impacted by the Refugee Influx in Kakuma Camp, Kenya

Public Disclosure Authorized Rapid Assessment of Natural Resources Degradation in Areas Impacted by the Refugee Influx in Kakuma Camp, Kenya Technical Report November 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................. vi Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................................ vii Executive summary................................................................................................................................................ viii 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Objectives of the assessment ................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Area of interest ......................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Socio-economic findings .................................................................................................................................. -

One Size Does Not Fit All: Mitigating COVID-19 in Humanitarian Settings

One Size Does Not Fit All: Mitigating COVID-19 in Humanitarian Settings Executive Summary April 2020 COVID-19 has already overwhelmed health systems in high-income countries. As it spreads to fragile and crisis- affected countries, it threatens even greater devastation. There is a small window left to mount a robust response while COVID-19 is still in the early stages of spreading to these settings. COVID-19 is a global threat requiring a global response, but the steps to contain it should be designed locally, particularly in the crisis settings where the International Rescue Committee (IRC) works, to avoid exacerbating humanitarian suffering. In the face of an unprecedented threat, governments worldwide have understandably followed the models of those countries hit first by COVID-19 to mitigate the impact of the disease. Many have swiftly adopted measures like lockdowns and strict travel restrictions. But a one-size-fits-all model will not work. This is especially true in humanitarian settings, which face a “double emergency” from COVID-19: the direct health impact and its secondary devastation to these states’ fragile humanitarian, economic, security and political environments. In humanitarian contexts, living conditions make social distancing nearly impossible, workers in informal sectors cannot transition to working from home, and governments are unable to provide sufficient relief packages or social safety nets. Sweeping mitigation measures like those undertaken in Italy or the United States will not just be difficult to implement but could cause longer term and more widespread harm than the disease itself. Already, international and domestic restrictions have slowed the transportation of COVID-19 equipment, halted vaccination campaigns, disrupted supply chains of treatment for malnourished children, and prevented medical staff from being deployed in countries with weaker health systems. -

Doing Business in Kakuma: Refugees, Entrepreneurship, and the Food Market

Doing Business in Kakuma: Refugees, Entrepreneurship, and the Food Market Alexander Betts, Antonia Delius, Cory Rodgers, Olivier Sterck, Maria Stierna Credit: N. Omata Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 6 2. Methodology 9 3. Who is Doing Business? 11 4. Business Practices 13 Suppliers 13 Relationship with Customers 15 Business Strategy and Operations 17 Employees 20 Capital 21 Law and Regulation 24 5. Market Structure and Competition 25 Products 25 Price Competition 25 Sales, Expenditure, and Profit 29 Market Geography and Competition 31 6. External Interventions 32 Business Training 32 Supply Chain Development 34 7. Conclusions and Recommendations 37 Acknowledgements 44 Published by the Refugee Studies Centre, ODID, University of Oxford, September 2019. Designed by Katy Dawkins. Printed by Oxuniprint. Citation: Betts, A., Delius, A., Rogers, C., Sterck, O., Stierna, M., (2019), Doing Business in Kakuma: Refugees, Entrepreneurship, and the Food Market (Oxford: RSC). Cover photo: Market in Kakuma refugee camp. Credit: World Food Programme Grocery shop Executive summary • The Kakuma refugee camps have become popularly of non-applicant food retailers, sampled from a Norwegian associated with entrepreneurship. From the International Refugee Council (NRC) census. In total, we interviewed 730 Finance Corporation’s Kakuma as a Marketplace study1 entrepreneurs (of whom 629 currently have a business). We to the bustling retail markets and restaurants in Kakuma complemented the survey with qualitative data collection One, the proposed Huduma-Biashara Business Centre, and based on semi-structured interviews and focus groups. the new market based Kalobeyei settlement, the Kakuma Our aim was to examine what role BC status, among other camps have become an exemplar of the shift towards private factors, has played in influencing business performance and sector-led development in refugee contexts.2 market structure. -

United Nations Development Programme

United Nations Kenya Country Office Host Community Projects in Kenya Project Initiation Document (PID) Budget: $USD 2,016,925 Funding Source: UNHSF - Japan On behalf of: Signature: Date: Ministry of State for Special Rachel A. Arunga, CBS, Programmes, OP Permanent Secretary UNDP Elizabeth Lwanga Resident Representative Ms Olivia Yambi, UNICEF Country Representative Burkard Oberle WFP Country Director UNHCR Mr Eddie Gedalof, Country Representative December 2007-November 2009 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ 2 List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ 3 Project Site Map .............................................................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Project Definition ............................................................................................................................ 9 Project Scope and Exclusions .................................................................................................... 10 Defined Method of Approach ................................................................................................... -

REFUGEE CRISIS OVERVIEW a ABOUT ADOPT-A

room future - a - ww.unausa.org/adopt Future - A - Adopt visit: , on information more For grow and learn can community and $30,000 $30,000 and students where classroom new a builds • help. our need they but world, the around settings other children Rohingya of classroom one for facilities generation by educating refugee children in camps and and camps in children refugee educating by 600 600 $1 supports the construction of 2 WASH WASH 2 of construction the supports • prevent a lost lost a prevent working to to working are UNHCR and USA - UNA room trauma by affected children conflicts. escalating $750 $750 trains a teacher with methodologies to support support to methodologies with teacher a trains • curricula, family economic issues and problems created by by created problems and issues economic family curricula, students to enroll in school. in enroll to students of previous studies, different languages of instruction and and instruction of languages different studies, previous of $250 $250 school uniforms and supplies for 10 10 for supplies and uniforms school provides • primary education primary , such as the recognition of certification certification of recognition the as such , Refugees for Commissioner High UN What does it cost to help refugee children? refugee help to cost it does What problems in accessing accessing in problems additional experience Refugees Grandi Filippo survival” basic beyond y education refugee children deserve. children refugee education y qualit the provide compared to a world average of 91 of average world a to compared . % deal with the refugee crisis, it is essential that we think think we that essential is it crisis, refugee the with deal younger generations in need. -

“Yes” in My Backyard? the Economics of Refugees and Their Social Dynamics in Kakuma, Kenya Report No: AUS14056

Public Disclosure Authorized IN MY BACKYARD? Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized “YES” MAYBE NOT The Economics of Refugees and Their Social Dynamics in Kakuma, Kenya Public Disclosure Authorized 2016 “Yes” In My Backyard? “Yes” In My Backyard? The Economics of Refugees and Their Social Dynamics in Kakuma, Kenya Report No: AUS14056 Republic of Kenya “Yes” In My Backyard? The Economics of Refugees and Their Social Dynamics in Kakuma, Kenya GMF07 AFRICA Standard Disclaimer: This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Develop- ment/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data- included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/.